- Share via

When he told his 19-year-old stenographer that they would both be arrested within 15 minutes, she believed him. She got in his car and they fled to Yuma, Ariz. There was no reason to doubt him. Paul Bourgeois was “America’s greatest animal trainer,” a pioneer cinematographer in the Dutch film industry, the inventor of a new “iceless ice,” the promoter of Los Angeles’ first full-size skating rink — and her boss.

In Yuma, Joyce Burns got a telegram from her mother, who told her to come home: It was only Bourgeois who was wanted by police.

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

“He admitted he had told me I was in danger so that I would come with him,” Burns told The Times after she got back to the city Aug. 22, 1916, a few days after absconding. “He told me he loved me and wanted to marry me.”

But on returning to L.A., Burns began to learn things about Bourgeois. He had stolen the car and another woman’s heart (as well as her money). He had stolen more than that. And he had never explained to anyone how his iceless ice was going to work.

Bourgeois wasn’t even his real name: It was Paul Sablon.

His accomplishments in European cinema had earned him a place in early film history, and his Hollywood pictures were hailed in the American press. But from 1916 until his death in 1940, Bourgeois never made another film, and scholars weren’t sure why. Archival records reveal the bizarre reason: Looking to take advantage of a new fad for ice skating, Bourgeois pretended to invent an ice that wouldn’t melt in Los Angeles, took heaps of investors’ money and ran.

That the entertainment industry attracts greedy opportunists loose with the truth will surprise no one. In just the latest example, actor Zachary Horwitz last month agreed to plead guilty to running a massive Ponzi scheme, wheedling more than $650 million out of investors with made-up movie deals at HBO and Netflix. The little-known century-old story of Bourgeois not only shows that it was ever thus but also foregrounds perennial questions that bedevil America (before and after its reality-scammer president). When do benign hucksters become malignant frauds? And why do people fall under their spell?

Actor Zachary Horwitz collected $690 million from investors for movie deals the FBI says were fictitious.

Bourgeois and his wife, actress Rosita Marstini, arrived in Hollywood in summer 1915 after he made a name for himself as a gifted animal trainer in New York. He had set up a school that trained animals to perform on film, an innovation that likely brought him to the attention of Carl Laemmle, who was building an enormous studio for Universal Pictures in the San Fernando Valley.

“It was a functioning city,” says UC Santa Cruz professor Shelley Stamp, author of “Lois Weber in Early Hollywood.” “It had a post office and a little hospital and a fire station. It was an amazing place to work.”

It also had a zoo to house the stars of the studio’s popular animal shorts. To run this vast new enterprise — and market its films — Universal’s chief was in need of talent with a knack for self-promotion.

“Laemmle very frequently used the word ‘go-getters,’” says Bernard Dick, author of “City of Dreams: The Making and Remaking of Universal Pictures.” No one was more of a go-getter than Bourgeois.

“Would you go into a cage with a tiger?” he reportedly asked one of the world’s most famous opera stars, Ernestine Schumann-Heink, when she visited Universal City his first month on the job. She agreed and called it the greatest thrill of her life — greater than singing for composer Gustav Mahler and being made an honorary citizen of 10 countries. “Am praying for you every day,” she telegrammed Bourgeois after the visit. “I am your true and faithful friend.”

Success came quickly for Bourgeois, who had a talent for donning new hats when opportunities arose. He had begun his career in Europe as a cinematographer for Pathé Frères, jumped in front of the camera when a production needed an actor willing to do a dangerous stunt and learned to train animals with the help of the nature documentarian who directed his first films. Bourgeois’ first picture for Universal was a riotous two-reel comedy, “Joe Martin Turns ’Em Loose.” A series of collaborations with Marstini followed, with Bourgeois credited as actor, writer or director and his wife as the star.

“It was relatively easy in the early days to move from acting to directing, or screenwriting to directing, or back and forth,” says Stamp. “There was an interesting kind of fluidity” that helped husband-and-wife teams thrive. Yet the actress formerly known as the “Countess de Marstini” (though there is no evidence of her nobility) in “A Prisoner in the Harem” (1913) was billed in their films simply as “Madame Paul Bourgeois.” Would it be unusual if Marstini had had a greater hand in writing or producing these films than the credits suggest?

“Absolutely not. That’s the downside of husbands and wives working together,” says Stamp. “After the fact, the men were almost always credited with all of the work, or the majority of the work, and in many cases, that wasn’t true at all.”

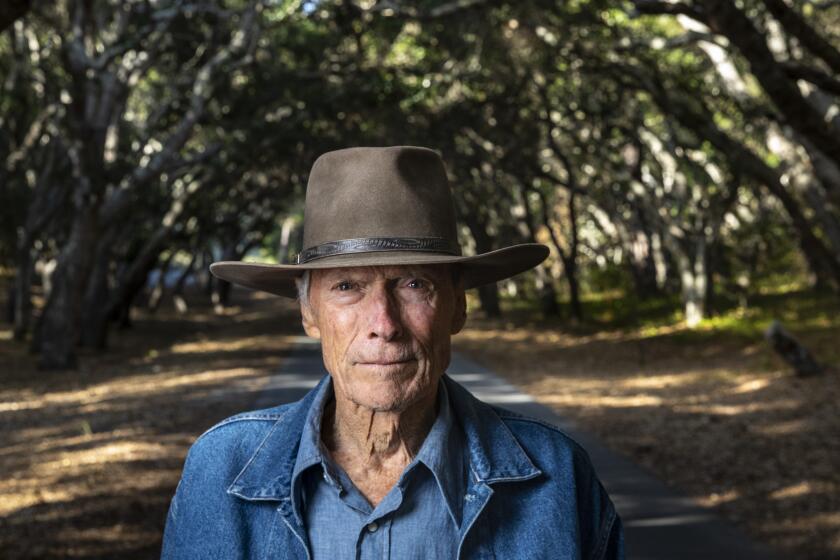

With ‘Cry Macho,’ Clint Eastwood may be the oldest American to direct and star in a major motion picture. But ask if anything has changed since his start and you get the verbal equivalent of an amused shrug.

The media likewise made little note of Marstini’s skill at working with the world’s most fearsome creatures, preferring to pepper Bourgeois with questions about his trade.

“My method of training wild beasts is as simple as ABC,” he told a reporter. “Oppression and cruelty will turn any lion into a demon, while firmness, kindness and patience — infinite patience — will make him as gentle as a tabby cat.”

But Bourgeois wasn’t always a patient man. In September 1915, he was charged with animal cruelty, accused of beating a lion to death, reportedly for not posing correctly during filming. Two months later, he found himself in the Universal hospital after his hand was crushed by a bear. Perhaps it was then he realized that the career of an animal trainer could be a short one. A profile from his time in New York noted that his hands, neck and back were already striped with scars.

Yet no private correspondence survives that explains why Bourgeois turned away from filmmaking. Geoffrey Donaldson, a seminal Dutch film scholar, once asked Bourgeois’ second wife about it, but she was unable (or unwilling) to disclose more, other than to say he had “lost interest” in film, preferring to work in the steel business — go figure. All that’s known is that by spring 1916, a restless man with a gift for reinvention found himself working as one of many filmmakers at a large Hollywood studio, with a reputation for animal abuse, a history of injuries and, perhaps, a broken marriage.

On March 2, 1916, the fashionable Café Bristol, on the ground floor of the Hellman Building at 4th and Spring streets downtown, debuted a new attraction for Los Angeles: a skating rink. Skating was already enormously popular, and cafe rinks were a fad in New York and Chicago. But they were expensive. The Bristol’s 24-by-50-foot surface required a $10,000 ammonia refrigeration system.

Bourgeois, finger to the wind, sensed an opportunity. Among his many skill sets was some knowledge of chemistry. Though his education record is unclear, a 1907 document from a train crossing the U.S.-Canadian border indicated he worked as an electrician in Manitoba. He told acquaintances that he’d received a deferment from service in the Belgian army during World War I because the U.S. Navy was interested in an alloy of his invention, although no record of this exists. In April 1916, he claimed to have invented “iceless ice.”

“Mr. Bourgeois claims that this composition cannot break, unless deliberately chopped up, it cannot wear out and it cannot melt, unless put on a fire,” The Times reported. “The composition is laid down in liquid form and ‘freezes’ over, or hardens, in twenty-four hours.”

The limited number of ice rinks in Southern California and the competing demands of figure skaters and hockey players used to turn figure skaters into nomads in search of practice time.

Bourgeois secured investment to convert a roller rink and car dealership at 1041 S. Broadway into the Palace Ice Rink. The grand opening was to be attended in July 1916 by the mayor and feature L.A.’s first game of ice hockey. The entrance was constructed to resemble a huge iceberg. Inside were shops that would sell candy, ice cream, cigars and soft drinks.

Vendors paid Bourgeois hefty deposits to secure places in the venture. Cashiers could get a job if they paid $100. Dozens of skating instructors lined up to offer lessons to wobbly Angelenos. Bourgeois needed $17 from each of them to purchase a uniform.

Contractors, still busy through the summer, were paid almost entirely with checks that bounced. The builders sought out Bourgeois to find out how his ice was supposed to work, but he couldn’t be reached. A vendor named Jacques Levi reported him to the authorities, and a warrant was issued for Bourgeois’ arrest on Aug. 4, by which time he, his stenographer and his investors’ money were on their way to Yuma.

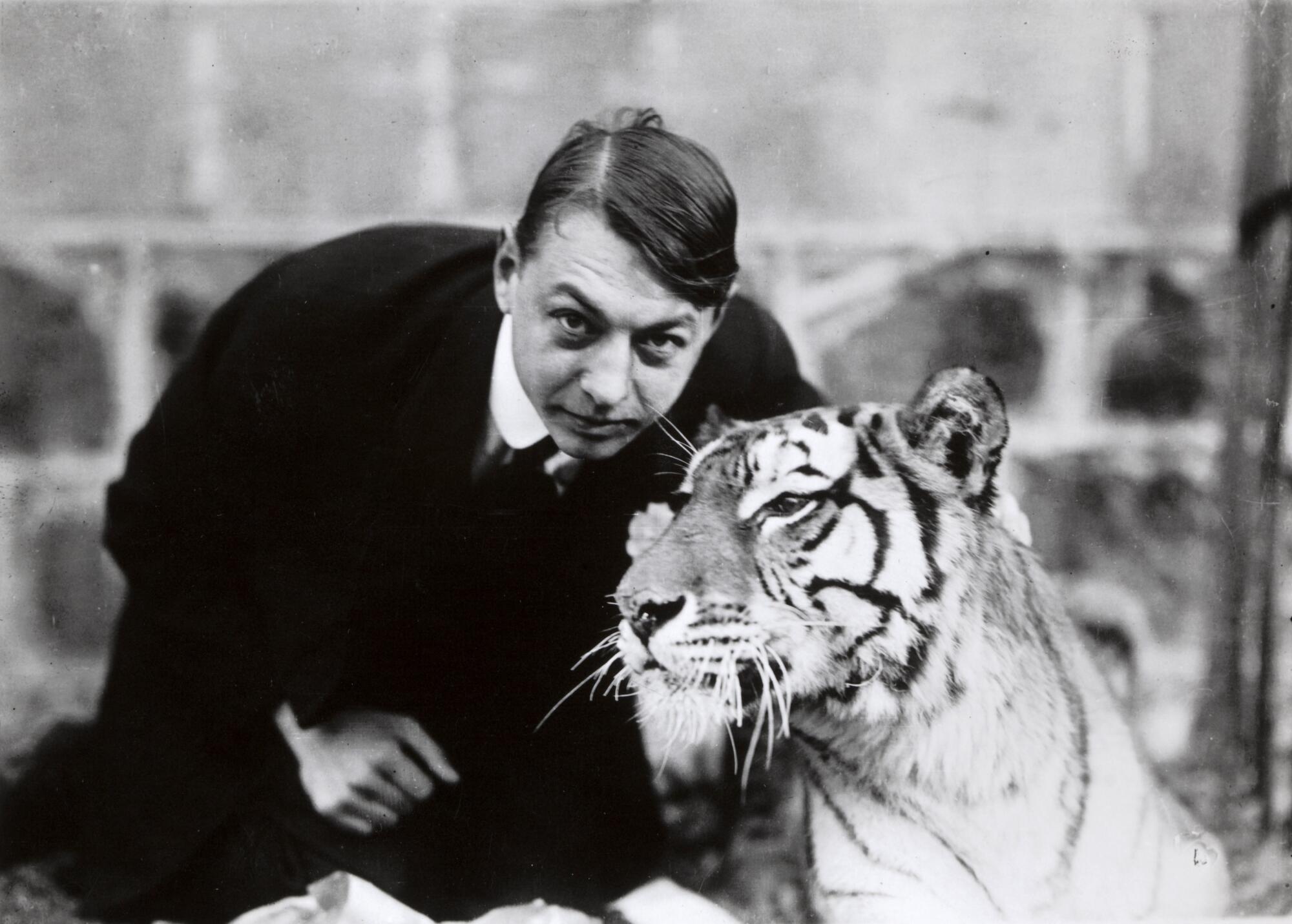

The first time Bourgeois appears on-screen, in the 1912 Dutch film “Het vervloekte Geld” (The Curse of Money), he’s down on his luck and arguing with his girlfriend. Tall, lank, his head slightly stooped, Bourgeois could be mistaken for shy, something noted later by American journalists. Was it this boyish manner that made him a successful con?

“It’s an interesting and famous film,” says Rommy Albers, senior curator with the Eye Filmmuseum in Amsterdam. “Geld” is the story of a greedy businessman who pays an alcoholic sailor to sink his ship so he can collect the insurance money.

“There’s a lot of films in the Netherlands about fraud with fishermen,” says Albers.

So Bourgeois, whose film career ended with an arrest warrant on suspicion of fraud, got his start playing the victim of one. His character dies on the ship and returns in a vision that terrifies the guilty sailor.

Bourgeois seems not to have been haunted by his victims. L.A. authorities found out about the stolen car, but Bourgeois evaporated. He went abroad and reclaimed his original name. There’s some evidence Paul Sablon returned to Chicago and sought citizenship in 1923 — but then the trail goes cold again. He married a second time in Europe. He told his second wife he’d found work as a tinkerer, first in the U.S. steel industry and then in early television electronics in England and North Africa. He died of kidney disease in 1940 in Brussels. He was 51.

Imagine a movie industry where women write half the films, where renowned female directors are the rule and where casting couches aren’t a fixture in the boss’ office.

Burns, the stenographer, danced in Busby Berkeley films and married one of the top cinematographers at Fox. Marstini kept acting, starring opposite Rudolph Valentino Valentino and finally got a writing credit for a play that the Los Angeles Herald described as “dealing with the battle between a clever woman, versed in the ways of the world, and a crook.”

Did Burns and Marstini — or the dozens Bourgeois was accused of swindling — ever suspect anything when they looked into his gray eyes? Was it just his charm that made his lies believable, or was there more art to it?

Perhaps there is a clue in what he once told a reporter about winning the trust of the big cats he trained to perform on film.

“All the young trainer asks is to study his beast, and to understand how best to flatter it.”

Johnston has written about history and culture for Atlas Obscura, Maclean’s and the Toronto Star and has taught at Algoma, Stony Brook and Western universities.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.