Why artist and engineer Xin Liu sent her wisdom tooth into outer space

- Share via

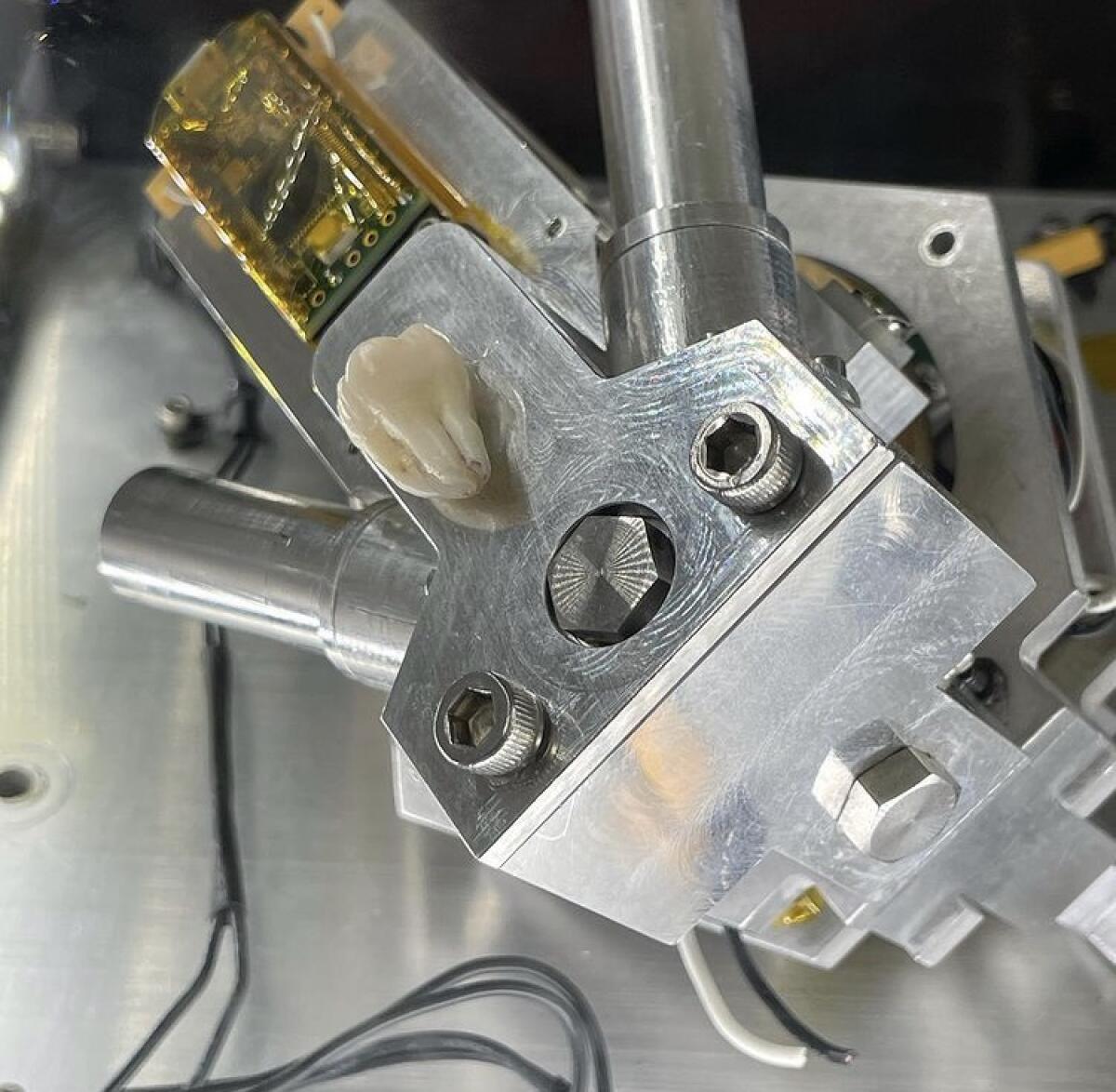

Artist and engineer Xin Liu put herself out there for her “Living Distance” project — literally. The New York- and Beijing-based artist packed up her wisdom tooth and sent it into outer space in a custom machine built from robotics materials. The tooth launched from Van Horn, Texas, in May 2019 aboard an early iteration of Blue Origin’s New Shepard rocket. In zero gravity, the machine and the tooth floated around, freely, inside the rocket.

Wait, what?

It’s all in the name of art. The tooth is part of the sculptural installation “Synthetic Wilderness,” on view at Culver City’s Honor Fraser Gallery through Dec. 18. The three-artist show, which includes L.A.-based Nancy Baker Cahill and New York-based LaJuné McMillian, blends digital media with more traditional art forms. It toggles between augmented reality, performance, immersive drawings, and video and digital photography, among other areas. The exhibit occupies a hybrid space, both analog and digital, meant to reflect the “new terrain,” as exhibition curator Jesse Damiani puts it, that is the 2020s — a tumultuous and uncertain period marked by trauma, pronounced bewilderment and rapid change.

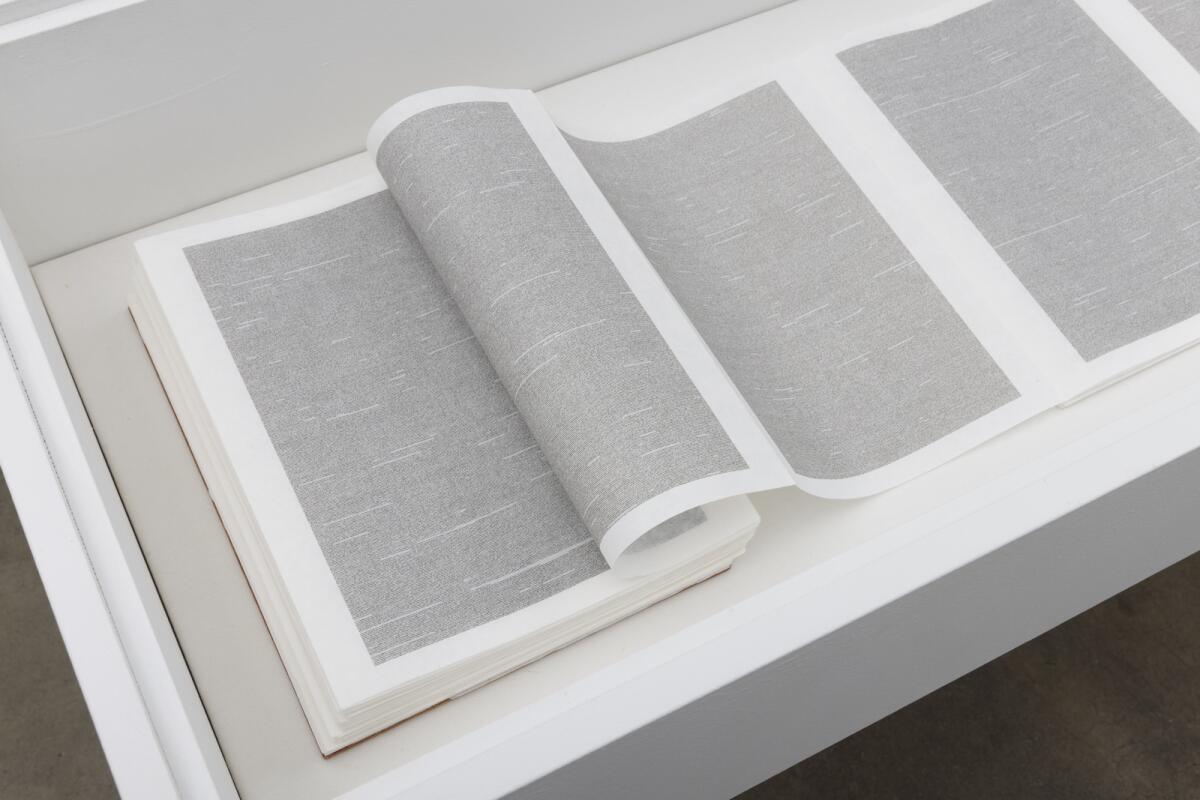

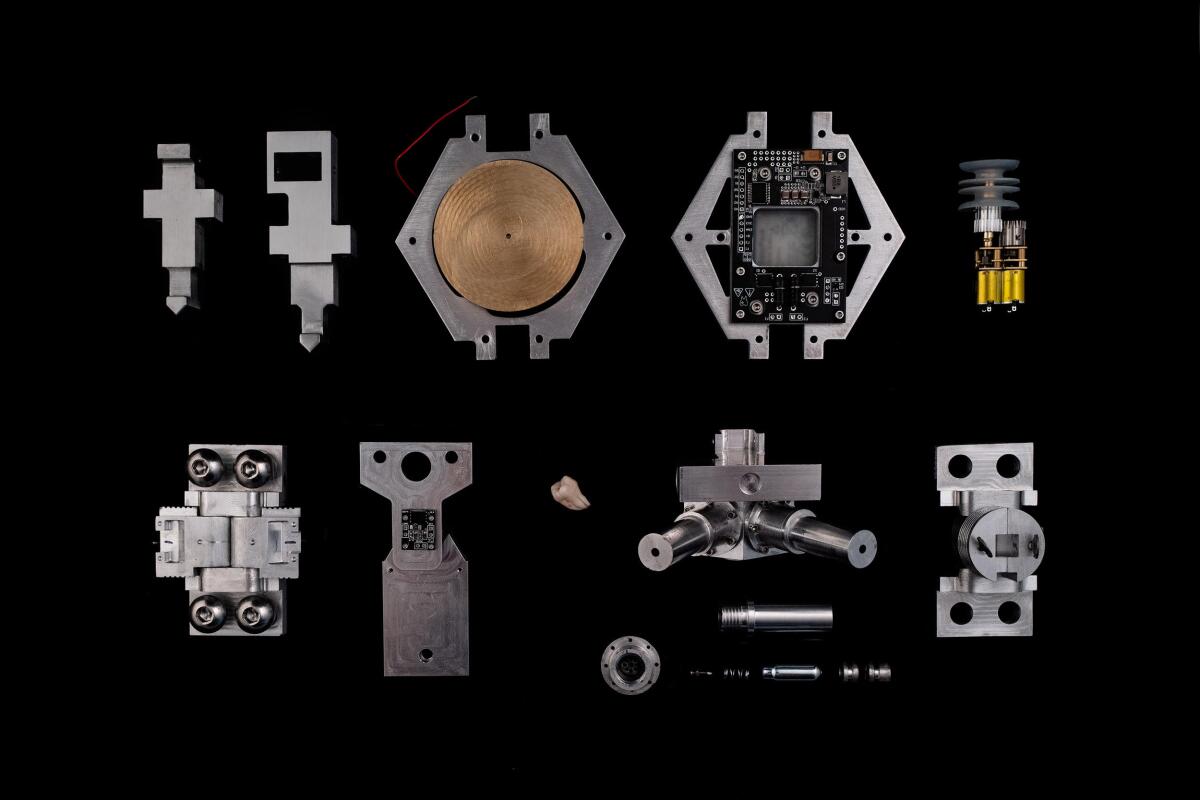

Liu — who is arts curator of the MIT Media Lab Space Exploration Initiative and an advisor to the Art + Technology Lab at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art — used the launch of her tooth as a springboard for other works in “Synthetic Wilderness.” There’s also a two-channel video documenting the making of her tooth sculpture; a digital photograph of the sculpture’s disassembled parts, forming what looks like a scientific cross-section; and a more than 1,000-page, accordion-style book, made of rice paper, featuring Liu’s sequenced X chromosome from her DNA data.

The work explores geographic and phenomenological boundaries — between the self and the other, between Earth and outer space — and it asks “what it means to have part of me leaving, so far away, and how to give birth to another being?” as Liu explains in this edited conversation.

Why launch your tooth into space — and what’s the larger “Living Distance” project about?

“Living Distance” is both a personal fantasy and a serious space mission. A wisdom tooth is sent to outer space and back down to Earth again. Carried by the crystalline robotic sculpture, the tooth becomes a newborn entity in outer space.

The material and the texture of the tooth seem to be a perfect fit to me. It is essentially a bone (quite hard, like ceramic) but also visually so fragile. It is part of my body but also a separate piece itself.

Did you remove your tooth for the piece or you already had it? And how did you arrange for its journey into space?

I had it already at the time. I had an impacted tooth and had to have it pulled out.

I was and am still working with MIT Media Lab Space Exploration Initiative. The initiative has various mission opportunities that students and researchers can apply for. I applied for this suborbital launch opportunity to test my spider-mimicking locomotion technique — something I incorporate into performance — in actual outer space. The opportunity I got was for technical innovation, not for my artistic vision. I had just graduated from MIT then, and there was no way a young artist like me would have had such support for an art project.

How is the piece a continuation of your previous performance work related to space exploration?

In 2017 I did a performance work, “Orbit Weaver,” in a zero-gravity flight in Florida with a company called zero-G. I was performing like a spider woman moving around and trying to connect with the surroundings using threads. In that performance, I feel that I was in a simulated outer space, and in this one, it was reversed: I created a simulated me, an avatar of myself, and performed in the real outer space.

How does the work, conceptually, explore the idea of boundaries, passage and ceremony?

In many ways, the distance created geographically or physically is a metaphor and is reflected in the emotional and spiritual experience. I think that the desire to leave and the destiny to return echoes with my personal journey. I was born in Xinjiang, China, and moved to Beijing when I was 18 and I moved to the U.S. in 2013. Hopefully it speaks to the shared history and experience of many people.

The action of sending a tooth to outer space is very much a ceremony and a performance for me. It is not a fiction, it’s an act that I am conducting as I’m thinking about the questions mentioned above.

Can you tell us about other works in the show?

The photography of the sculpture is to show how its parts are designed, the details inside. It is a very elaborate electromechanical system. The book is the X chromosome of my DNA. I printed out the whole X chromosome sequence on Japanese rice paper. Then I handmade (folding, cutting, gluing) this accordion book of mine. These two works are very much connected as they both ask the question about what we’re made of and what we will become.

DNA is the source code of all creatures on Earth. But as we set sights on outer space, this organic body isn’t the most suitable of forms anymore. Our body isn’t made for the extreme environments out there. So, as we are longing for the departure, leaving Earth, aren’t we also abandoning ourselves, our body? Perhaps the humanity that finally leaves Earth isn’t human anymore. How do we feel about that? Is there a point where we shall return?

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.