- Share via

Blood, sweat and snot — and Dior Backstage Eyeshadow Palette in neutral tones.

These are the images that rushed to mind, unfiltered, upon stepping into Laurie Kang’s art studio the other day.

The Toronto-based Kang is the inaugural artist-in-residence at Horizon Art Foundation, a new downtown L.A. nonprofit nurturing emerging and midcareer artists from around the globe. Horizon provides artists — four a year for up to three months each — with working and living spaces in L.A. as well as a stipend. Next up: Sara Cwynar, Phillip John Velasco Gabriel and Ilana Savdie. The goal is to free them up, for about three months each, to create experimental work in an environment unfettered by deadlines and the pressure to exhibit.

Kang is just now finishing up her residency, so we swung by to see what she’s been up to.

The 4,500-square-foot space, in a Fashion District warehouse, was flooded with late morning sunlight when we arrived. Twelve-foot-long sheets of glossy, unfixed film hung like drying animal skins from the ceiling, “tanning” — her term — through the windowpanes. They’d turned gradations of beige, taupe, purple, rose and gold. A cluster of bowls on the floor, in varying sizes, held aluminum-cast food items — a school of sperm-like anchovies in one, a halved cabbage head with its veiny flesh facing upward in another — floating on what looked to be pools of soup or bodily fluids but is actually poured silicone.

The organic, carnal feel to the work makes sense. Kang, an identical twin who works in photography, sculpture and installation, is clearly interested in the ever-morphing human body and issues of identity.

“I really feel like my work is so much about setting up situations for change,” Kang says. “We are porous beings, we are always in a state of becoming in relation to other bodies and the environment around us.”

Horizon Chief Artistic Director Christopher Y. Lew says the organization chose Kang — who is 37 and considers herself someplace between an emergent and mid-career artist — to kick off its residency because she’s at a tipping point in her career.

“We were excited to bring in someone thinking about installation and experimentation with mediums,” he says. “Plus, given her presentation at the 2021 New Museum Triennial — she had this ambitious installation involving wall studs and more of her experimental photographs — we thought this was an apt time for her to expand on her practice and get to know L.A.”

The sheets of hanging film, as wide as twin bedsheets and affixed to light tracks on the ceiling that Kang sees as the veins and arteries of the space, is an installation called “Molt.” The material is meant to be developed in a controlled darkroom, then the image placed in a lightbox, like in a bus shelter, and backlit. Instead, Kang explains that she is “misusing” the material, exposing it to sunlight and letting the colors emerge organically. The work morphs with the day’s light, moving between opacity and translucence, at times monochromatic and other times featuring bleeding color blocks, like a Rothko painting. In this way the material itself embodies the concept of change, particularly as it pertains to the body.

“It has a lot to do with the continual state of becoming — for a body, but also what that means for photography, to unfix an image,” Kang says, adding that the title refers to the shedding of skins. “And the colors — they all kind of feel like they’re of a body. Bruises or marrow or blood. Interior colors.”

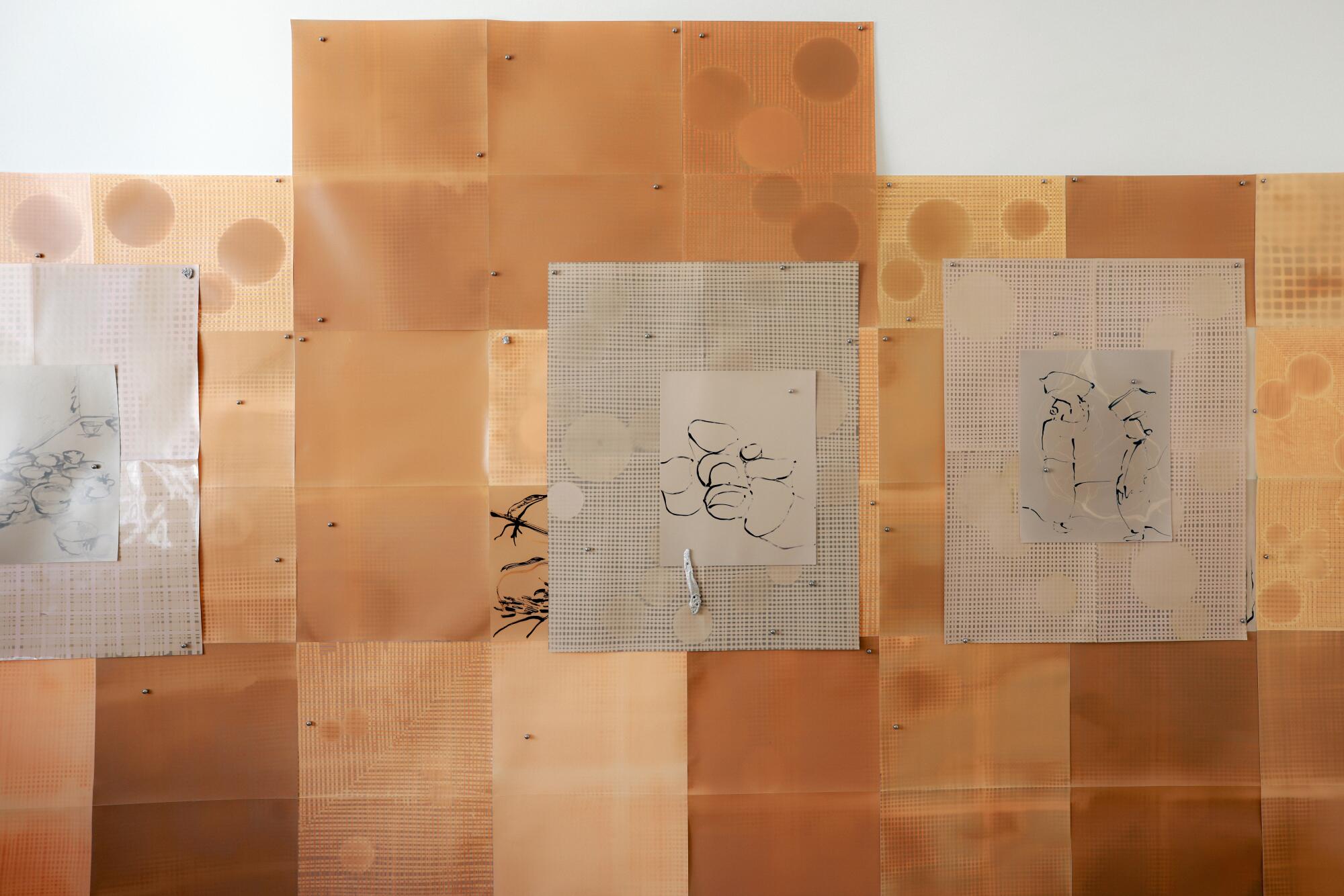

A series of photograms, collaged works featuring line drawings and cast rubber formations, is called “Mesoderm.” Kang weaves a grid of artist tape over the paper — which she thinks of as skin — then tans it in natural sunlight. The drawings, including figures carrying vessels on their heads and abstract shapes, are made with darkroom chemicals.

“I’m not trying to be skilled in my renderings; I’m more trying to express an effect through the line,” Kang says. “There’s a double helix, our DNA, so working with that shape as well as other anatomical shapes such as nerves, spinal cords.”

Kang draws heavily on her Korean heritage to make work, she says. “Mesoderm” is informed by a traditional Korean quilt-making process called bojagi. The installation of stainless steel bowls, which Kang sourced from a Korean kitchen supply store, is shaped by her upbringing. It’s called “Mother.”

The bowls’ “innards,” as Kang refers to them, are cast aluminum food items in what looks like tinted liquid in hues of nude, cream, gray and peach. The liquid is translucent and lustrous looking; but it could also be read as muddied water, spoiled soup or sickly bodily secretions. A pile of silvery chestnuts floating in one resembles tiny brains. Curvy Asian pears look almost organlike in nature. A cast-silicone tube, coiled around a lotus tuber, looks like a human umbilical cord.

“For me, food is a way to think about things that are outside of us going inside and then going back out, how they spiritually accrue in our bodies and change us over time,” Kang says. “I’m mostly using food objects familiar to me in my upbringing, which feels like they’ve sort of calcified in me or become almost part of my internal skeleton or scaffold.”

Kang says there are no concrete plans for the work’s future yet. Horizon artists retain sole ownership of the work they create there. She has a solo show in March 2023 at Chisenhale Gallery in London and some of the work might turn up there. But mostly, the months at Horizon have been a time to unfurl, she says.

The studio’s vast space — compared to her 300-square-foot Toronto studio — allowed her to spread out, literally and figuratively.

“It’s almost like a garden in here; it feels like there are different plots for the things I can work on separately but tend to at the same time,” she says. “It’s been so expansive for me to have that space.”

Which has resulted in personal transformation, as well.

“It’s really allowed me to grow and change,” she says, “and have a deeper understanding of the intimacy between all these seemingly disparate parts.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.