The late composer behind ‘RoboCop,’ ‘Conan the Barbarian’ gets his due at Disney Hall

- Share via

In the mid-1960s, USC’s campus became a creative hotbed, attracting a staggering number of future famous filmmakers. George Lucas, John Milius, Walter Murch, Randal Kleiser and Caleb Deschanel were all members of what Lucas dubbed “the USC Mafia.” Milius, who went on to write “Apocalypse Now,” called it “the class the stars fell on.”

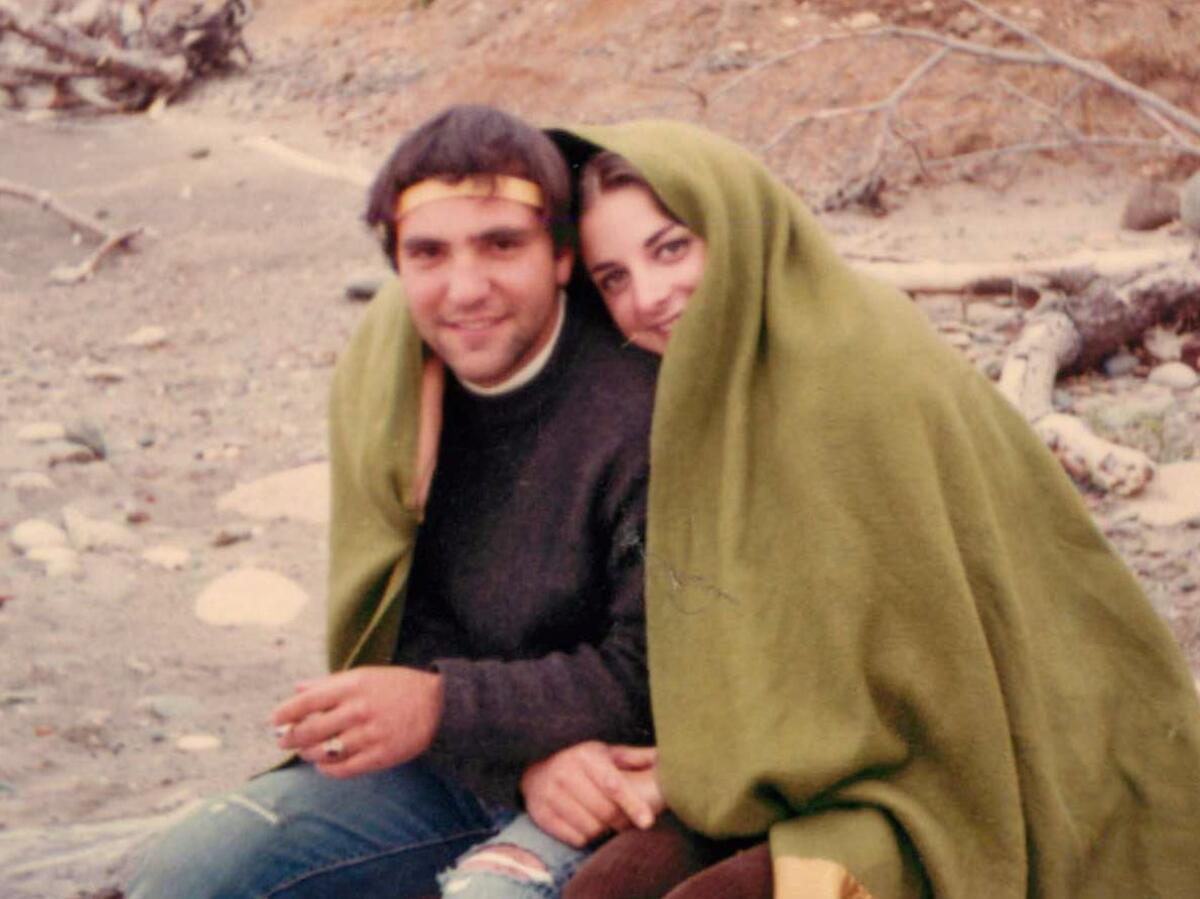

Sitting in film classes next to them was Basil Poledouris — a gentle, laid-back surfer who wore a hippie’s leather hat and “was just one of the gang,” says writer-director Matthew Robbins. “We were all making student films, and he was one of them.”

After graduation they all went into different areas of the business — writing, cinematography, editing, directing. But when Robbins saw Milius’ surfing film “Big Wednesday” 10 years later and realized that its grandly romantic, orchestral score had been composed by Poledouris, “I was just totally gobsmacked,” he says. “I had no idea that he had this gift.”

Poledouris proceeded to write scores for more than 50 feature films — including “The Blue Lagoon,” “Conan the Barbarian,” “RoboCop,” “The Hunt for Red October” and “Free Willy.” He honored the grandeur of Hollywood’s golden age, updated for the blockbuster era, and his muscular themes and gentle folk melodies became permanently attached to several iconic characters.

But Poledouris’ career never quite caught fire the way it did for some of his peers — among them James Horner, Danny Elfman and Hans Zimmer — and although he won an Emmy for the miniseries “Lonesome Dove” in 1989, he was never nominated for an Academy Award. In 2006, he died of lung cancer at 61.

This year marks the 40th anniversary of his breakout score for “Conan,” and on Friday an overdue tribute to Poledouris’ career will be paid at Walt Disney Concert Hall. The event is being staged by the Los Angeles Film Orchestra and Chorale, a new outfit founded by Steven Allen Fox, a regular conductor of film music concerts. It will be hosted by longtime soundtrack producer Robert Townson and feature Resident Choir maestra Marya Basaraba. Former classmates Milius and Kleiser will be in the audience.

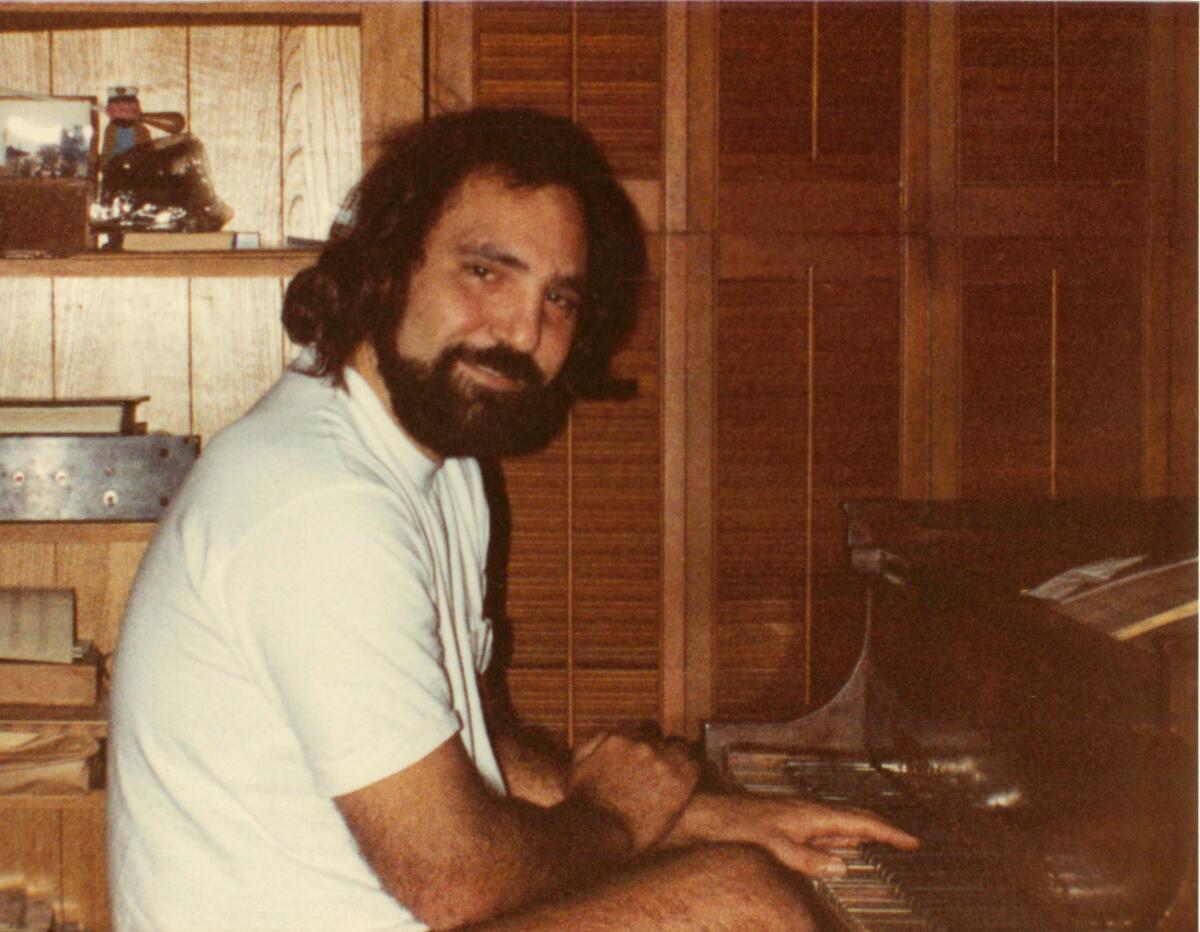

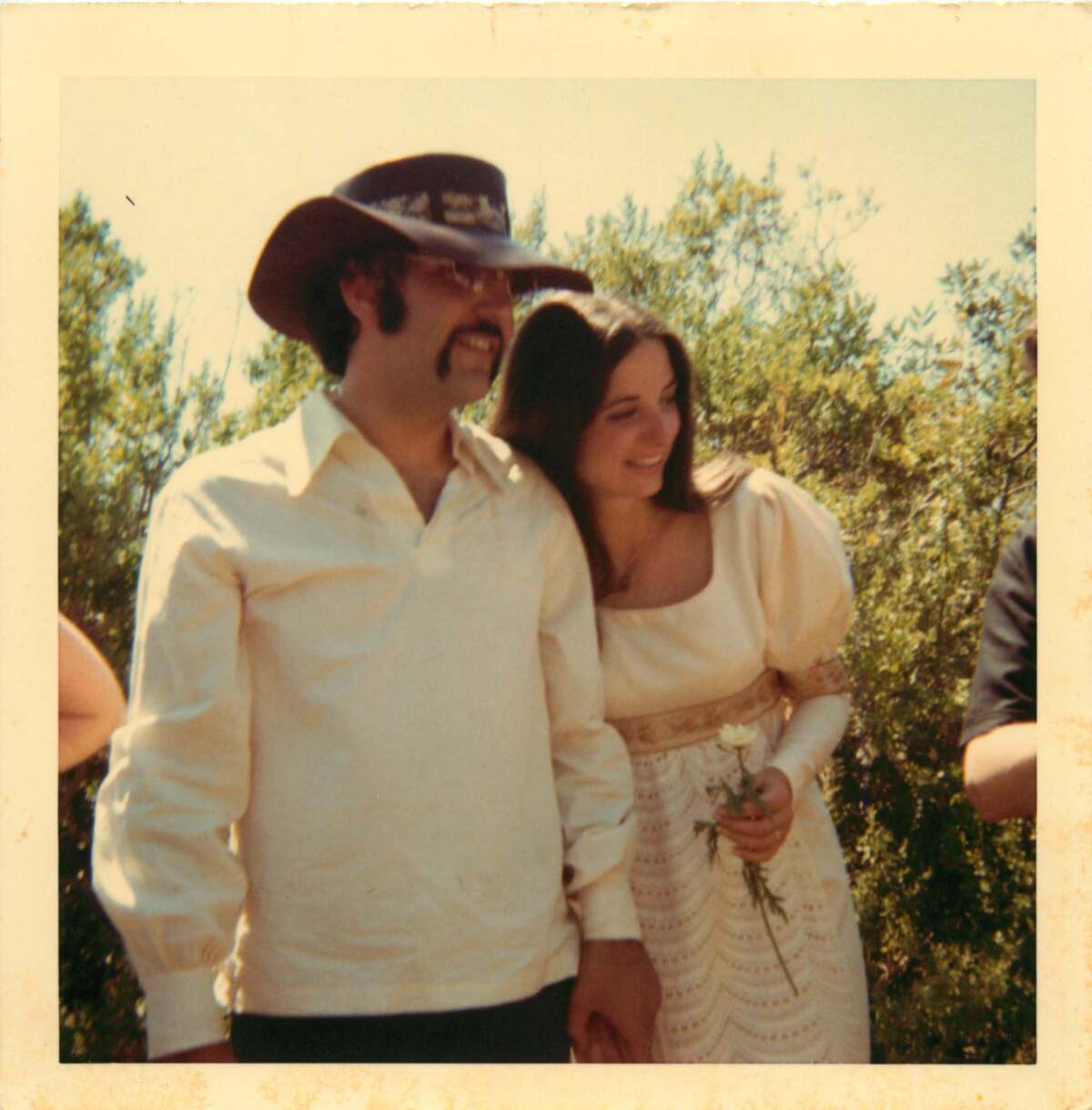

When Bobbie Poledouris met her future husband in 1965, she also had no idea he was a budding composer. She was a freshman at USC, and on their second date they were at a friend’s house. The friend turned to Bobbie and said: “Don’t you love the way Basil plays piano?”

“I said, ‘I didn’t realize that he played piano,’” she recalled. “He said, ‘Oh, well, Basil play for her!’ [Basil] sat down and said, ‘I composed this piece of music after our first date last week.’”

The son of a Greek immigrant, Poledouris grew up in Garden Grove, where he graduated in the same high school class as Steve Martin. He was a gifted piano player from the jump, and played in a folk band called the Southlanders. Poledouris earned a full music scholarship to Cal State Long Beach, and was studying piano and composition when one of his teachers told him: “I don’t like what you’ve written here. This kind of garbage could probably make you a lot of money in Hollywood.”

So he quit music school and went to film school, where his directing work included a prize-winning short about a boy’s day on a fishing pier.

“My first impression of him was his beard,” says Milius, who would go surfing with Poledouris. “We quickly became very close friends.”

Milius says he learned Poledouris was a composer on the first day they met. Deschanel, the Oscar-nominated cinematographer of “The Natural,” also knew he was a great musician at the time since they had co-created scores for student films.

“To say ‘wrote’ is not really it,” says Deschanel. “We would just sort of sit around and play some things, and ‘What do you think of this riff?’ and ‘How about if I do this and then you play the piano?’”

After “Big Wednesday,” which expressed Poledouris’ lifelong love of the sea, his score for “Conan the Barbarian” amplified the story of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s taciturn warrior with heroic swells and folk-like melodies that recalled the epics scored by his own hero, “Ben-Hur” composer Miklós Rózsa.

The Garden Grove High School class of 1963 was studded with future entertainers.

Poledouris specialized in music that was mythical — cinematic hymns and ballads that sounded ancient and emotionally naked.

“Basil was really able to capture the feeling in my work and knew exactly what I was trying to convey in my films,” says Milius. “Every time. He was incredibly versatile. He wrote from the heart, right to the heart of each film.”

His other frequent collaborator was the Dutch director Paul Verhoeven, and his theme for “RoboCop” — the blood-soaked 1987 satire — was an instant classic that reflected the half-man, half-machine protagonist with a stern brass march over glinting electronics.

He became associated with testosterone-heavy pictures, but Poledouris was an unabashed romantic. He got to explore those emotional depths in movies like “The Blue Lagoon,” Kleiser’s drama about two children who come of age on an island. But even the macho Milius gave him a chance to write sweeping, sensitive tunes in films like “Farewell to the King,” an old-fashioned epic starring Nick Nolte.

“The Hunt for Red October,” the first adaptation of Tom Clancy’s Jack Ryan novels, boasted a thriller score that wove together soulful melodies, effervescent synthesizers and the vocal stylings of a Russian choir.

His friends described him as a gentle bear, which is also a pretty accurate way to describe his work.

By 1990, Poledouris had enough pedigree for his agents to apparently land him “Dances With Wolves” — a perfect match for his romantic muscle that would surely have taken his career to new heights. But when he realized it conflicted with Milius’ new film, the forgettable Vietnam flick “Flight of the Intruder,” he pulled out of Kevin Costner’s multi-Oscar-winning film out of loyalty to his old college friend. “That was Basil,” said his agent, Charles Ryan.

The ’90s yielded several family films, notably “Free Willy.” A smart and touching story about an abandoned boy who befriends a captive killer whale, it earned comparisons to “E.T.” and became one of the biggest hits of 1993.

“The score is the heart of the film in a lot of ways,” says Jason James Richter, the film’s star. His character, Jesse, communicates with the whale by playing a Poledouris tune on his harmonica. The music “is the relationship between Jesse and Willy,” Richter said. “It’s the emotional glue.”

Poledouris gave similar soul to a live-action remake of “The Jungle Book,” Sam Raimi’s baseball film “For Love of the Game” and a 1998 adaptation of “Les Misérables” starring Liam Neeson — all with indelible tunes and earnest emotion.

Hollywood’s tastes were changing, though — Zimmer and others ushered in an acceleration of technology and a decline in lush melody — and Poledouris found himself a man out of time.

“All the curses of contemporary film scoring came battering down on Basil,” agent Richard Kraft wrote in a 2013 blog post. “Even though he was still a young man, I believe Basil identified more with the [Bernard] Herrmann’s and the Rózsa’s than what was becoming increasingly popular.”

Great opportunities dwindled in his last years, and he retreated from the world somewhat. While in treatment for stage IV cancer, he was able to ride one last wave of admiration when he conducted the score of “Conan” in Ubeda, Spain. He died a few months later.

Several composers who were there in Spain — including John Debney (“Elf”) and John Frizzell (“Office Space”) — will conduct selections at Disney Hall, as will Christopher Lennertz (“The Boys”), one of Poledouris’ proteges.

“I miss his music, and hearing him play the piano,” said Bobbie Poledouris. “And I miss the music that never got written.”

'Basil Poledouris: The Music & The Movies'

Where: Walt Disney Concert Hall, 111 S. Grand Ave, Los Angeles

When: Friday, July 22

Admission: $50–175

Info: lafilmorchestra.com

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.