School book bans have increased 33% since last year, but hope is not lost

- Share via

Despite growing lawsuits and protests against book restrictions, bans continue to spread rapidly, according to a new report. But students are providing a glimmer of hope.

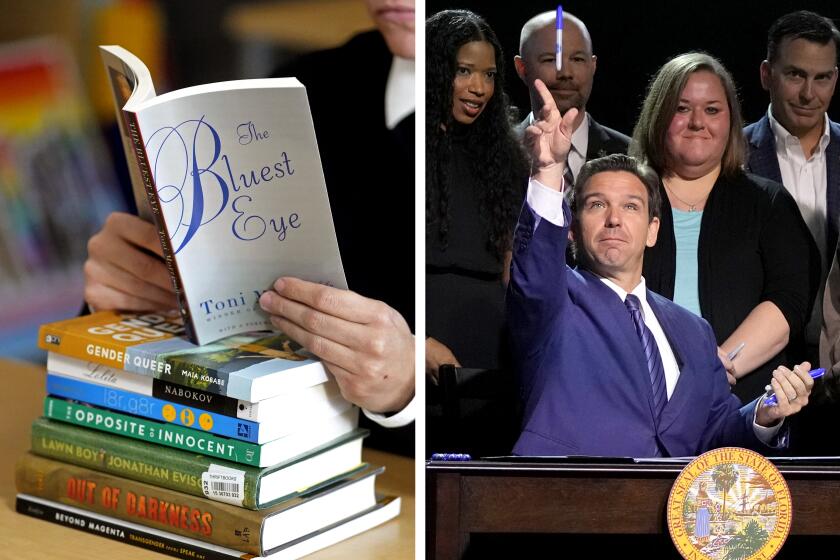

PEN America’s annual report on book bans, released Thursday, revealed a significant ramp-up in the practice during the 2022–23 school year. Between July 1, 2022, and June 31, 2023, the national freedom-of-speech organization recorded 3,362 instances of book bans in US public school classrooms and libraries — an increase of 33% compared to the same period last year.

“The toll of the book banning movement is getting worse,” said Suzanne Nossel, chief executive of PEN America, in a statement obtained by The Times. “More kids are losing access to books, more libraries are taking authors off the shelves, and opponents of free expression are pushing harder than ever to exert their power over students as a whole.” The bans, she continued, “are eating away at the foundations of our democracy.”

Library and LGBTQ+ advocates offer educators tips on how to respond when LGBTQ+ books come under attack in their school or district.

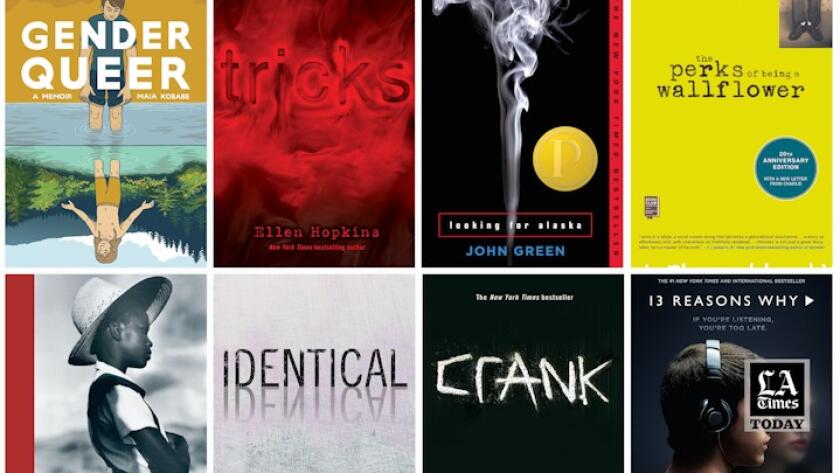

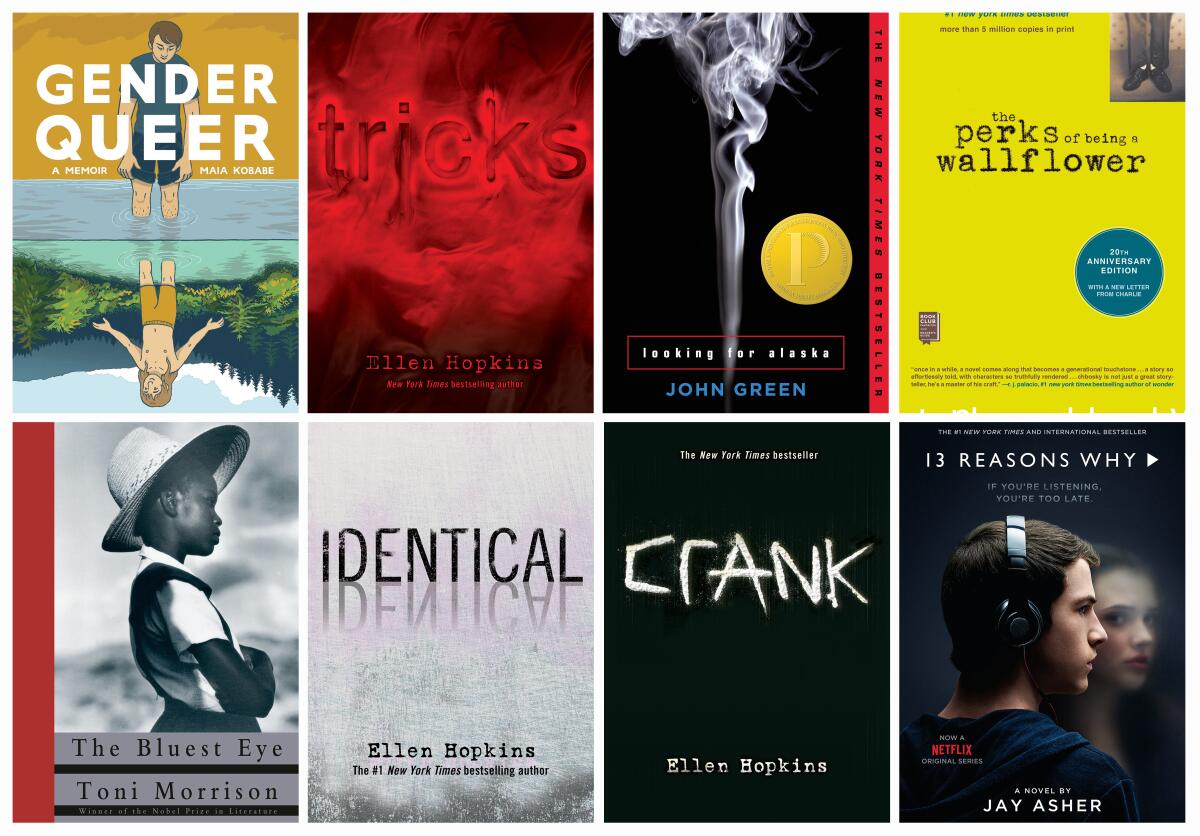

According to the report, “Banned in the U.S.,” these actions have restricted student access to 1,557 unique book titles by more than 1,480 authors, illustrators and translators. Authors whose books were challenged were disproportionately female, people of color and LGBTQ+ individuals. Nearly half of banned books addressed violence or physical abuse, including sexual assault; 30% depicted characters of color and themes of race and racism; 30% represented LGBTQ+ identities; and 6% included a transgender character.

While the majority of book bans were aimed at middle grade books, chapter books or picture books, titles for teens were a high point of contention, especially those that explored sexuality.

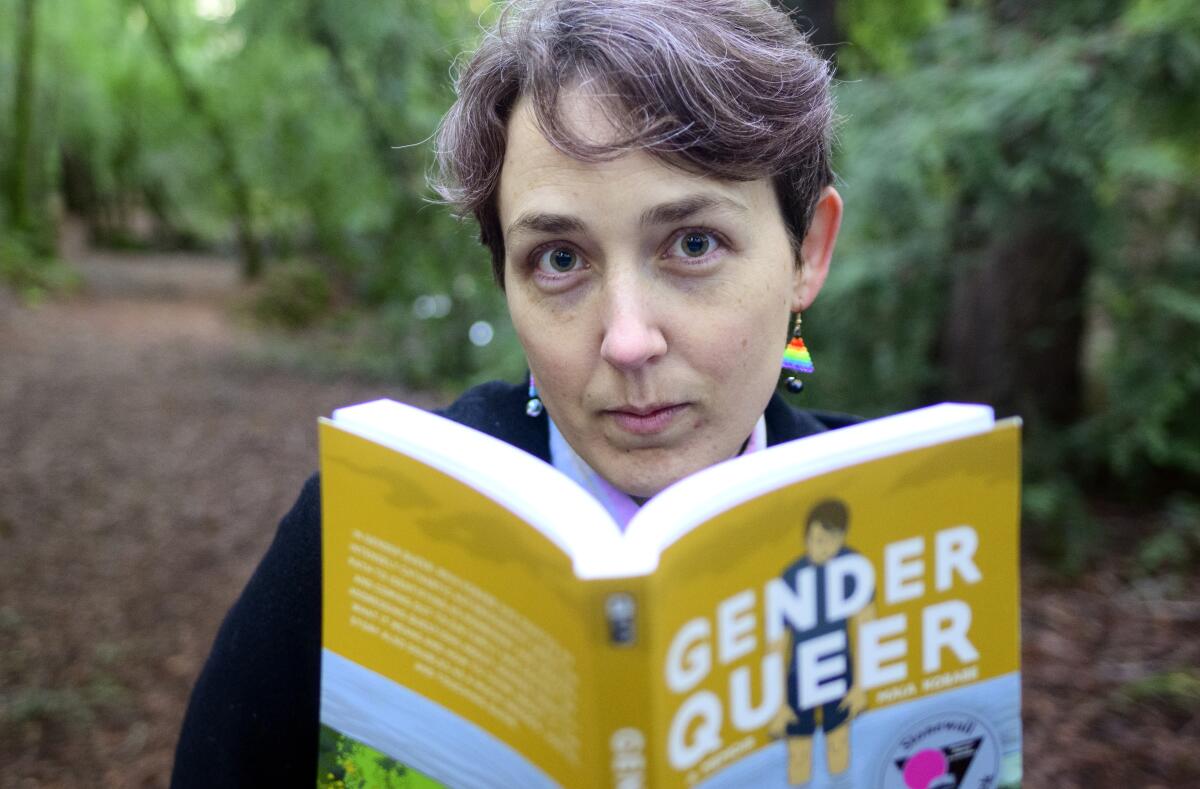

Last week, Sen. John Kennedy (R-La.) went viral for an awkward reading of excerpts from two books targeted by conservatives during a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing titled “Book Bans: Examining How Censorship Limits Liberty and Literature.” One of the titles, listed for older teens, was Maia Kobabe’s memoir about gender identity and sexuality, “Gender Queer,” which was banned 26 times according to the PEN report.

Even books with historical merit, such as Amanda Gorman’s acclaimed poem, “The Hill We Climb,” were not exempt from restrictions. Written for and read at Joe Biden’s 2021 inauguration, the poem was challenged earlier this year in Miami-Dade County by a parent for being “not educational” and including indirect “hate messages.”

Maia Kobabe’s graphic memoir “Gender Queer” became the most banned book in American schools, drawing the Northern California artist and writer into the nation’s cultural wars.

That incident sparked discussion over what exactly a book “ban” entails. Gorman defined it in a statement posted to X (formally known as Twitter): “A school book ban is any action taken against a book that leaves access to a book restricted or diminished.” PEN America defined it in their report in much the same way, adding that by definition they override the decisions of educators and librarians.

“While I’m encouraged by PEN America’s work to protect free expression and intellectual freedom, it’s disappointing to see such a steep rise in the banning and restriction of books,” said author John Green, whose book “Looking for Alaska” was the third most frequently banned book in U.S. schools, according to the report. “We should trust our teachers and librarians to do their jobs. If you have a worldview that can be undone by a book, I would submit that the problem is not with the book.”

More than 40% of book restrictions occurred in Florida. Across 33 school districts, PEN America recorded 1,406 book ban cases in the state, followed by 625 in Texas, 333 in Missouri, 281 in Utah and 186 in Pennsylvania.

The majority of book challenges are brought by parent- or community-led advocacy groups. PEN America identified at least 50 groups — including Moms for Liberty, Parents’ Rights in Education and Citizens Defending Freedom — who call for book removal through school board meetings and challenge forms. These organizations often empower individual “serial book challengers” who sometimes question more than 100 books.

PEN argues that these groups are exerting ideological control over public education, dubbing the book ban campaign the “Ed Scare” — a movement they say is using “educational gag orders” that weaponize state legislation and employ intimidation tactics to suppress teaching and learning about cherry-picked stories, identities and histories.

Amanda Gorman’s inaugural poem ‘The Hill We Climb’ was added to the book bans taking over Florida elementary schools

According to Kasey Meehan, PEN America’s Freedom to Read program director and lead author of the report, “Hyperbolic and misleading rhetoric continues to ignite fear over the types of books in schools. And yet, 75% of all banned books are specifically written and selected for young audiences.”

In May, Tim Smith, the superintendent of schools in Florida’s Escambia County, was terminated after standing behind a thorough committee review over the process of book removal. At the school board meeting during which he was summarily ousted, Smith decried the way book bans have been carried out, saying, “There’s something toxic that exists here. . . . If you care about kids, as you said, we need to do things right ... How much poison has dripped on that podium over the past six months?”

That same month, Penguin Random House filed a lawsuit against Escambia County to stop “one of the most unsubtle attempts at viewpoint discrimination” the publishing conglomerate had ever seen. Dan Novack, a lawyer for the world’s largest publishing house, offered an update Wednesday during an interview with The Times.

While the judge overseeing the case “hasn’t really sunk his teeth into it yet,” Novack said, the state has already acknowledged that the “Don’t Say Gay bill,” passed under Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis and cited by the county as grounds for book removal, did not apply to library materials.

Escambia has since pivoted by citing Florida’s HB1069, a new education law which became effective July 1, that restricts books depicting “sexual conduct” from grades deemed age-inappropriate. Many of the book bans in the county have nothing to do with sexual content, however, and focus solely on racial themes and LGBTQ+ content that does not include depictions of sex. One example: “And Tango Makes Three,” a widely banned book based on the true story of two male penguins who cared for an egg together.

PEN America and publisher Penguin Random House filed a federal suit against Escambia County School District over its removal of books from school libraries.

Earlier this week, Novack added, book-ban opponents scored a major win when federal judge Alan D. Albright — a Trump appointee — issued an opinion and order blocking Texas’ book rating law, HB 900, which would have mandated that booksellers rate books as a condition of placement in Texas public schools. “I think that people are going to start looking at this a little bit differently and not taking the conservative Judiciary for granted,” Novack said.

The PEN report also shines a light on another positive development: students across the nation who’ve had enough of their access to literature being encroached upon.

“Students have been using their voices for months in resisting coordinated efforts to suppress teaching and learning about certain stories, identities and histories,” said Meehan, the report’s lead author. “It’s time we follow their lead.”

This article was originally on a blog post platform and may be missing photos, graphics or links.

This spring, in Pennsylvania alone, middle school students walked out of Hempfield School District to protest changing policies in the district library, while student organizers in the Central York School District participated in daily protests. One student told Book Riot, “They see us as ‘just kids,’ but our voices matter, especially when they are voting on our education.”

Last year, students in Erie County, N.Y., launched the organization Students Protecting Education after showing up to their own school board meetings to fight the bans. One of the co-founders told PEN America, “We’re not fighting against something, we’re fighting for [it]. We’re fighting for our voices to be heard. ... And if you’re trying to take things away that we value, we’re going to let you know how we feel about that. We’re going to fight for those things we care about.”

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.