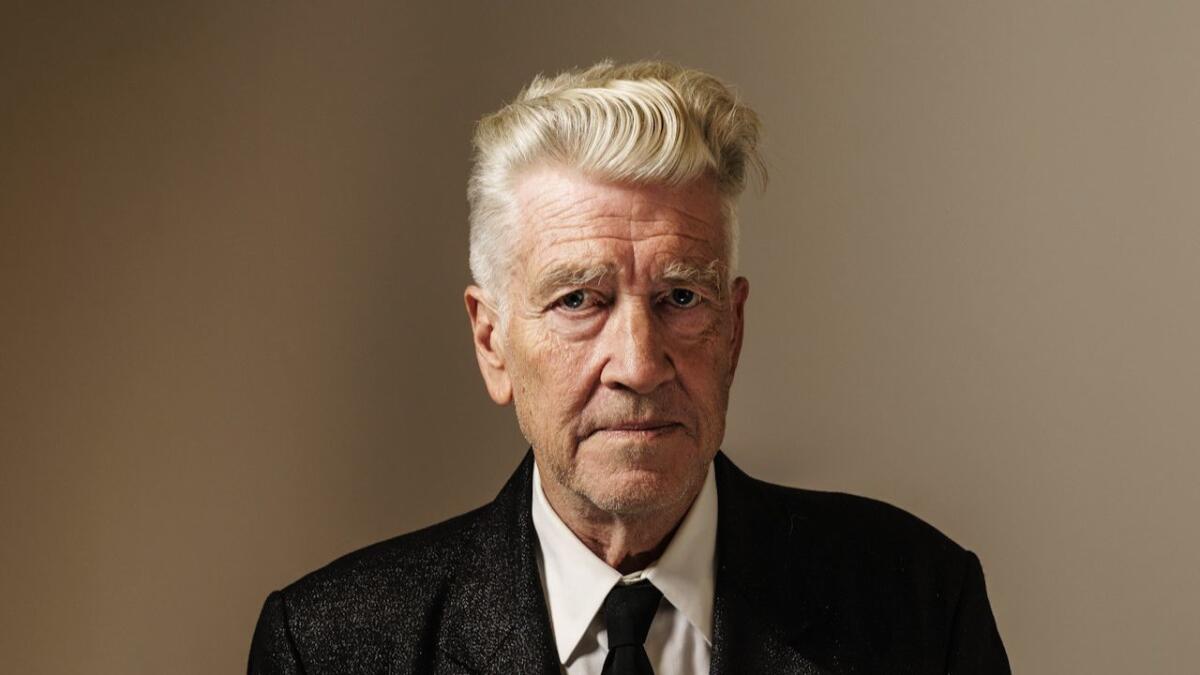

David Lynch inspired a cross-country lawnmower race. Things got complicated, fast

- Share via

A storm was coming one August evening near Lamar, Colo., and Andrej Sensnovis and John Zack — strangers just a month before — found themselves riding a lawnmower on a dirt road in the middle of nowhere as the light began to fade.

To avoid getting soaked, Sensnovis, 54, and Zack, 39, pulled into an unassuming driveway, and a large house suddenly emerged through the trees. When they knocked on the door and asked the man who answered if they could shelter in the garage, he insisted not only that they stay but also that they sleep in his own bed.

“There are good people in America — I mean, there are amazing people in America. I have so many stories, I could write a book,” said Sensnovis, of Kalamazoo, Mich., fighting tears. “I’m finding that there’s an abundance of help out there. You just have to ask and look for it, really.”

Sensnovis and Zack ended up staying for two days. The lawnmower, their only means of transportation, was busted. They spent the time getting it into working order.

The poignant stopover en route to Lamar occurred during filming for “The Great Grass Race,” an ultra-low-budget reality show inspired by David Lynch’s 1999 film “The Straight Story.” Based on real-life events, the Disney-released film follows Alvin Straight, played by Richard Farnsworth, as he drives a lawnmower 300 miles across America’s heartland to make amends with his ailing brother. Straight, aged and fragile, leans on and learns from the salt-of-the-earth souls he meets along the way.

“Richard embodied the spirit of love and forgiveness” in his portrayal of Straight, Lynch wrote in an emailed statement in late August.

Unlike Straight’s story, though, “The Great Grass Race” is animated by a competitive edge. After “racing” 3,000 miles from Los Angeles to Tampa, Fla. — a destination shifted from New York City at the 11th hour because of COVID-19 restrictions — to claim a nebulous prize of “up to $100,000,” contestants crossed the finish line in mid-September and the winners were announced, though the exact prize money was not.

It was a slow slog through punishing heat and slashing rain at 5 mph, the lawnmowers’ maximum speed. Required to embark on the journey without money, racers were forced to beg strangers along the way — in person and on social media — for gas, food and shelter. In the middle of a deadly pandemic. But numerous contestants described surprise at how much they were given — from hotel rooms to homemade chicken soup to a limousine ride — all at the helpers’ expense and for little exposure. The kindness exhibited by these “helping hands” is the crux of the show’s concept, according to creator Denis Oliver.

For ‘The Bachelorette’ and ‘Big Brother,’ two series with fraught histories around race, meaningful treatment of the subject has been a challenge.

“We know that showing the generosity of people, showing that love that we have in us, that everyone has — we’ve changed lives,” the Frenchman said in late August, speaking by phone from Oklahoma, where production was located at the time.

Episodes of “The Great Grass Race” were initially posted almost every other day during filming on watch.menacevision.com, which Oliver launched to house content for his fledgling network, Menace Vision. Cosmos Kiindarius, the show’s cameraman-turned-director, said the goal was to portray the events in near-real time. Eventually, the racers, who tricked out their lawnmowers to double their speed, outpaced production. With fans bound to learn the outcome through social media, the producers took the unusual step of posting the conclusion of the race before the episodes had caught up. They then picked up the narrative where it left off.

“Our true audience really didn’t care about the race,” Kiindarius said. “They care about this human experience, this human journey and what these people went through to get here.” There are currently more than 40 episodes, and new installments will run through November.

Aesthetically, the reality show and the film are diametrically opposed, but at times they vibrate at the same frequency. In Lynch’s film, Straight nearly destroys his lawnmower (and himself) when a mechanical failure sends him careening down a hill. A retired John Deere employee (James Cada) invites Straight into his home, where he ends up camping out and kibitzing with the locals until his lawnmower is repaired. It’s a sweet, sensitive scene that echoes Sensnovis and Zack’s experience in the backwoods of Colorado.

But Oliver didn’t stick around long enough to find out what happened to Straight. He said he turned off Lynch’s film once inspiration struck — about 10 minutes in — and immediately started developing the show, his first-ever foray into the entertainment industry. Yet “The Great Grass Race,” perhaps inadvertently, is a Lynchian reality show — based on arguably the director’s least “Lynchian” film.

“We keep waiting for the other shoe to drop — for Alvin’s odyssey to intersect with the Twilight Zone,” Roger Ebert wrote in a review of “The Straight Story.” And in “The Great Grass Race,” it lands with a thud.

‘We’ll be picking up your bodies for weeks’

The contestants arrived in Los Angeles around July 10 with a kaleidoscope of life experience: Clinton Brand, 23, an aspiring rapper from Paso Robles, grew up in the foster care system and is currently homeless. Kassie Sisco, 34, an aspiring model and actor from Newkirk, Okla., found out she had lupus just before the show began. Karima Spates, a 44-year-old single mom of three boys from Newark, N.J., is considering law school as a next step. Most described surprise at the speed of the audition process: Some signed up just days before filming began.

Soon after launch, the production became plagued by problems. Several crew members dropped out within a few days. Los Angeles-based cameraman Pedro Gonzalez said he was looking forward to what was supposed to be a three-month trip across the country but couldn’t stay with the project in light of the disorganization.

Fellow cameraman Phillip Darlington lasted about a week, though he calls that time — during which he witnessed a Thai restaurant owner in L.A. feed a desperate contestant — a “spiritual experience.” His final straw came during a run-in with a California Highway Patrol officer who stopped contestants and crew along a highway in Newhall, Calif. According to Darlington, the patrol officer told him that with trucks speeding around the blind curve where the racers were plodding along, “we’ll be picking up your bodies for weeks.”

“And that got under my skin because … he’s right,” Darlington said, adding that there was no medic — a resource he was accustomed to on a professional set. The run-in is depicted in the second episode. In it, contestant Tiffany Gil, a college student from Huntington Beach, looks at the camera and says they’re being shut down because the production “is inhumane.”

Officers responded to calls about lawnmowers and trailers swerving in and out of traffic on Soledad Canyon Road, right around the 14 Freeway, said Josh Greengard, an officer and spokesman with the CHP’s Newhall department. He said the lawnmowers lacked reflectors, headlights and taillights.

Driving through a canyon, “you can’t see too far ahead of you,” Greengard said, adding that cars going 65 miles an hour around a bend need about a second-and-a-half for reaction and perception. “By the time you brake, it’s going to be a little bit too late, especially if you have a vehicle that’s pulling from the shoulder into the roadway.” They were let go with a verbal warning.

Oliver said pains were taken to ensure the safety of contestants, including assigning cameramen in RVs to follow each lawnmower. Help, he said, was always a call away. He added that fans and bystanders spoiled the contestants, who ended up having more food than they could eat and more gas than their mowers could burn. (Several contestants and cameramen said the RVs broke down frequently and periodically became separated from the team they were supposed to tail.)

Oliver suggested the crew members left because they simply couldn’t hack it. Driving day in and day out, with plans constantly changing, isn’t for the faint of heart, he said: “They want to keep their pride. They’re supposed to be experienced, so ... they played that card.”

A contract signed by contestants and obtained by The Times includes a nondisclosure agreement. A first violation of the agreement results in a $20,000 penalty, a second $50,000 and a third $100,000. The contract states that contestants who leave the show before crossing the finish line owe the producers $100,000, with limited exceptions. It also limits the producers’ liability for injuries.

“People shouldn’t be allowed to sign these kinds of contracts,” Los Angeles-based entertainment attorney Bryan Freedman said after looking it over. “It’s kind of like signing a contract that says I can kill myself. It doesn’t comply with the law. These reality TV stars and reality TV people, for the most part, need to be protected against themselves.”

Oliver said that he felt the contract was fair and that contestants signed on with eyes wide open.

“If you participate in such kind of TV shows, you have to accept the risk that goes with it,” Oliver said. “We take our responsibility, and we make sure everyone is safe, but when someone has a day off and decides to do something on his own, you cannot be responsible for it. We cannot sleep with them, and be on their back constantly, to see what they do.”

Kiindarius noted that contestants were gaining something as well.

“For some of these people, who haven’t done anything significant in their lives, and maybe won’t have an opportunity to do anything else significant in their lives, that could be a really big deal,” Kiindarius said, “and I’m excited and happy for them.”

Meanwhile, Menace Vision is already in pre-production for one of its next shows, “Under Pressure.” An online trailer for the show says it will send 12 contestants into an underwater compound without sunlight or traditional meals for two months. “How many will survive?” text on the trailer asks before an animated shark lunges at the screen.

‘I might be done’

In one incident that eerily parallels “The Straight Story,” contestant Stephen Zampieri in mid-August found himself hurtling down a steep embankment on a lawnmower after it suddenly kicked into gear outside his hotel in Dodge City, Kan.

Without a means to steer or stop, and a truck looming in the too-near future, Zampieri, a 41-year-old ex-Marine living in Arvada, Colo., leaped off and rolled away from the vehicle, which soon crashed into a car. A good Samaritan rushed to his aid and drove him to the lone hospital in Dodge City. And unlike Straight, who lands just fine, Zampieri fractured his left wrist and was rushed into surgery.

At the beginning of September, after another surgery, Zampieri seemed defeated. “I might be done,” he said over text, along with a picture of his hand with what looked like a large metal hook sticking out of it.

Two days later, he changed his mind. He called from St. Louis to ask if I had any friends with a plane or boat who could take him — and his lawnmower — to the finish line. He said he wanted to prove that anything could be done with a strong enough will.

Zampieri never managed to make his mower fly or float. Vomiting from pain after his second surgery, he mounted his mower again and eventually crossed the finish line — placing third.

When Straight finally makes it to his brother Lyle’s house in Mt. Zion, Wis., in the film, the two men are so overcome with emotion they can barely speak. Lyle, played by Harry Dean Stanton, sheds tears as it dawns on him that his brother made the arduous journey by lawnmower.

Contestants of “The Great Grass Race” met a slightly less poignant end at the finish line on Sept. 16 at a park along the Hillsborough River in downtown Tampa. Sweating in the humidity, the racers patiently awaited the announcement of the winner order — which was based not just on who completed the race first but also on a complicated point system.

Gil took first place along with her teammate, Katie Knight. The next day, Gil said that she felt “really good” and that she and Knight had earned their place through hard work. But, she added, “I wouldn’t do it again.”

Awaiting his flight home in Tampa several days later, Zampieri wasn’t happy with the way things wrapped. He accused contestants Brand and Sisco of cheating their way to second place, and the production for aiding and abetting them. (Brand, Sisco and Kiindarius all denied these claims.)

Sisco and Brand weren’t pleased with the outcome, either. Despite crossing the finish line first, they were awarded second based on the point system and felt hoodwinked.

Kiindarius registered this bickering as irony. The show had in part set out to prove that American kindness trumped divisions portrayed in the media. “And now, all of a sudden [the infighting] is really rearing its head amongst our contestants,” he said.

Though Zampieri lost faith in the show, he hasn’t lost faith in its animating force. “If it wasn’t for the generosity of complete strangers, we’d be stuck in L.A. still,” he said. “That’s the straight-up truth.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.