Ken Burns looks at history through the eyes of its national mammal in ‘The American Buffalo’

- Share via

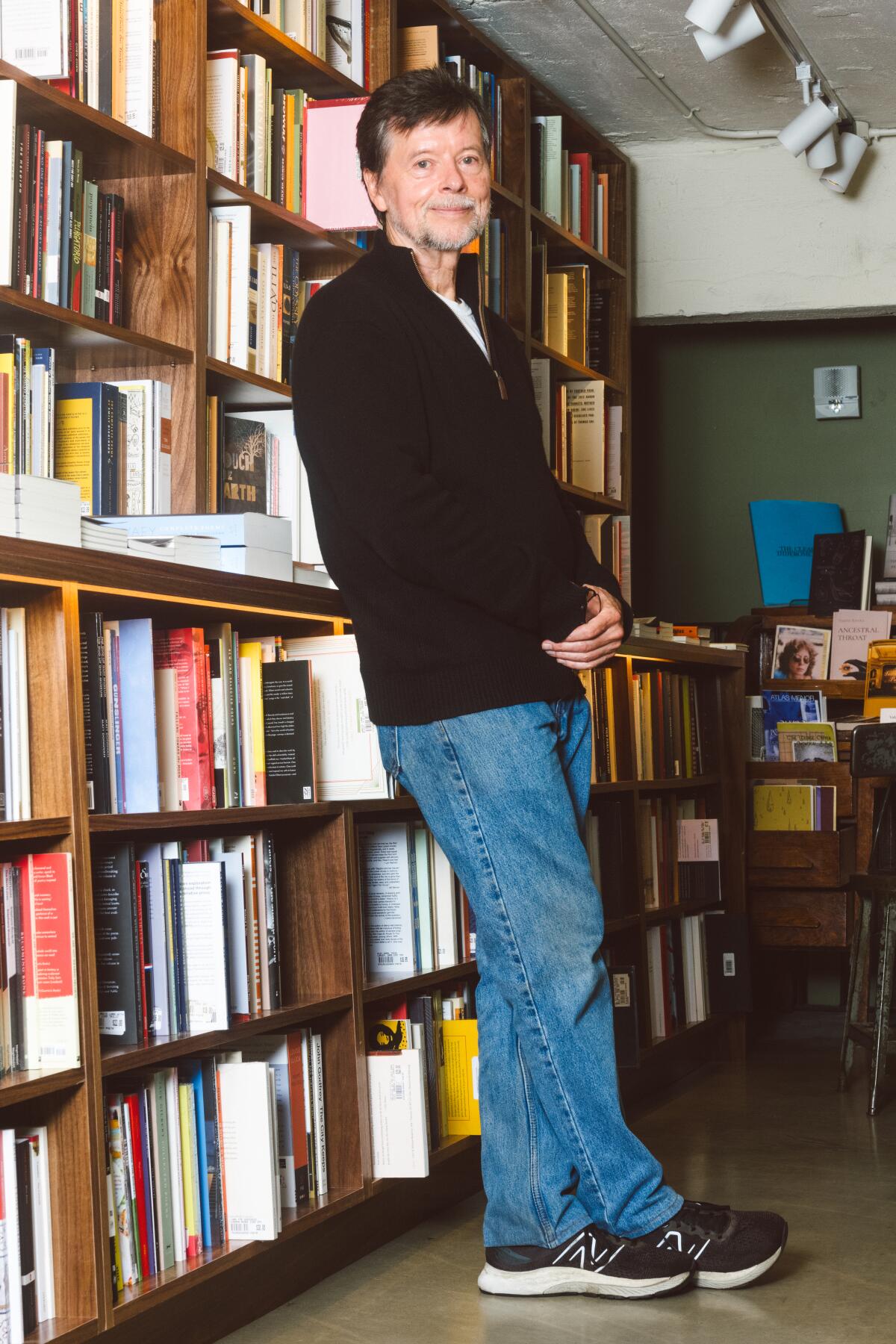

Documentarian Ken Burns has long chronicled chapters of American history, both writ large and in tiny, telling detail, connecting the dots from one scale to the other.

This month, he turns his eye to the epic saga of our national mammal, “The American Buffalo,” in a two-part, four-hour documentary for PBS premiering Monday. The story is, as he says, mostly a tragedy, but one with a surprising twist. Whereas once there were untold millions of the animals roaming from sea to shining sea, integral parts of the lives and cultures of many Indigenous tribes, “by the middle of the 1880s, nobody can find one,” Burns says of the buffalo, whose population declined sharply because of westward expansion. The animal’s numbers have since climbed back from the edge of the abyss, thanks to the efforts of many, including some unlikely benefactors.

Burns’ documentary isn’t just about that near-extinction, however, but what the buffalo has meant to the country and its people. When he was working on the series “The National Parks,” he suddenly found himself in the wintry wilderness of Yellowstone National Park, amid about 500 of the creatures, “all of them dusted with the confectioner’s sugar of snow. And you thought you were back in the Pleistocene.

“I mean, it was turn off the engine and just nothing. And they’re all huddled. And you go, ‘Oh, this is the way it was.’ And 500 would’ve probably been small and paltry; it might’ve been 5,000, it might’ve been 50,000 [back then]. But to have seen that, it was just such a great gift. I’ve always kept that idea of the buffalo as a project, as a biography alive,” he told The Times.

Premiering Monday on PBS, Ken Burns’ latest big documentary is on the big American bison, but really it’s mostly about people.

“Some early writer in the 19-teens, I think, was describing Mt. McKinley, what we now call Mt. Denali,” which stands more than 20,000 feet high and is estimated to be 60 million years old. “He said that it reminds you of your atomic insignificance. You’re nothing. You’re just a fly smack. You’re a nanosecond of a blip. When you feel your insignificance in the presence of nature — and this is not me, this is Thoreau and Emerson and Muir — you’re made larger.”

Burns spoke with The Times about “The American Buffalo,” which contains inspiring accounts of oneness with nature, chilling stories of sadism and bloodshed in a mad rush for profit (and worse motives) — and a message of hope rooted in the potential for transformation within human beings. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

What led you to this subject matter? Why the American buffalo now?

We’ve been thinking about this for more than 30 years, to do a biography of an animal to complement or contrast with all the other specific biographies or big-topic stuff that we’ve done. We’d intersected with that story in “The West” in the mid-’90s, again in the late-’90s with “Lewis and Clark,” and then in the aughts with “The National Parks.” I’m glad that we waited, because it gave us time. Scholarship improved. It also gave us the possibility to develop a narrative that wasn’t just going to pay lip service to other points of view in some paternalistic or even patronizing way, like allowing other points of view, but seeding the film with them.

This is a story in which there are divergent human responses to what the role is of human beings in nature. And so I think being able to do it now over the last several years has been a blessing because it allowed us to tell a much more complicated, a much more nuanced story and one that is not really complete. I think by the time we finished it, we realized our two parts were the first two acts of a three-act play. The third act is, “What are we going to do now?” Yes, the buffalo is saved. So our early ideas that this was a parable of de-extinction are true, but it’s so much more than that. Will they just be standing fenced in, in corrals or feedlots or whatever, sustainable, not going to go extinct, but can they roam wild and free the way they used to?

Most of American history is [presented as] top-down, just the sequence of presidential administrations punctuated by wars. What would it be like to do — as we’ve tried all of our professional lives to do — a bottom-up thing that would consider women, minorities, labor, other sorts of forces other than that “Great Man,” capital G, capital M, theory? What would it take to jump to a perspective through the eyes of an animal, to see this complex, 600-generation long, 10,000-, 12,000-year-long relationship with Native peoples where the buffalo is at the center of their existence in their creation stories, in their living?

Then, all of a sudden, the people who have only four or five generations of experience come in [the European settlers], and where perhaps there were 50 [million to] 60 million, no one can know for sure, buffalo in the continental United States at the beginning of the 19th century — by the middle of the 1880s, nobody can find one. There’s under a thousand. So this is the largest killing of wildlife in the history of the world.

The film is about more than the near-extinction of a species, though. As the narration (written by longtime Burns collaborator and “American Buffalo” screenwriter Dayton Duncan) says, “It’s a collision of two different views of how human beings should interact with the natural world.” To play on something you’ve said before, what’s the story that’s most of this history?

I think most of it is a tragedy. It is about disconnecting a whole group of people from an animal that they felt in kinship with over thousands of years. And it’s the story of another group of people who see themselves as superior, as the dominant species with permission to do anything they want to do. That’s Manifest Destiny: “We’re just going to roll over you. We’re going to roll over this land. We’re going to do what we want to do with it.” And you begin to see that perhaps that’s not the right way to interact with nature. Mark Twain is supposed to have said that “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes.” And we are dealing now with climate change and the possibility that many, many large charismatic mammals will go extinct.

The Native American participants [in the documentary] — some of them are scholars and historians and biologists, some are superintendents or retired Park Service people and some are just Native Americans from various tribes — they’re asking you to see things a little bit differently. When George Horse Capture Jr. [marvels at ranchers using the words] “My cattle, my property” — that’s like the rock in the middle of the stream around which everything flows. We’re all about property, we’re all about “my”; he’s asking you to see it differently.

The participants in the film, the scholars across the board, help rearrange your molecules to consider this idea of being separate from nature, as Dayton says, as the tragedy at the heart of the story. And [his] next line is, “You go a little bit further down the trail and it can give you hope,” and that has to be there too. We do save the buffalo. It is a good object lesson. We have more work to do with that and providing it an ecosystem, but it teaches us a lot about our own history.

You cover some efforts to return buffalo to contemporary tribes. But that doesn’t mean just looking at them; they use them in sacrificial rites, they eat them ...

Well, if you’ve got an animal at the center of your creation stories, the center of your spiritual practice, as well as the center of your life in which you’re using everything from the tail to the snout and from cradle to grave, this is a significant dislocation. If this animal has been missing, what’s it been replaced with? A Western diet that’s made you unhealthy and obese, as opposed to the lean, good cuts of the buffalo? A lot of people, they’ve misunderstood. The tribes aren’t taking them to have them as pets or as trinkets of some past thing. They’re killing them. But it’s sustainable. They’re eating them to try to reconnect to a diet that made them among the healthiest people on Earth.

We say at the very beginning of the film, for killing them, they revere them, right? “If the buffalo give themselves up, then we owe them something.” If they are the center of sustenance in a physical realm and spiritually, what does the loss of that mean? It’s starvation, malnutrition at best. But it’s also this poverty of spirit that the saving of the buffalo has helped.

The “hope” component of the film, in which people of very different backgrounds play key roles in pulling the buffalo back from the edge of extinction, is also about the evolution of some of those people, yes?

A lot of people move a lot of distance in their lives. TR [President Theodore Roosevelt] doesn’t go as far as we want him to. He’s still probably a white supremacist. He starts out thinking, “The buffalo are going to disappear, but that’s pretty good because it’ll help us with our Indian question.” You’re killing the Indian, or at least making them docile. But he migrates a little bit of the way; [naturalist and anthropologist] George Bird Grinnell helps him. You’ve got Quanah [Parker] who’s a [Comanche] warrior who makes the attack at Adobe Walls and then becomes friends with [Texas rancher] Charlie Goodnight, who himself makes a journey. He’s an Indian fighter and buffalo killer, and suddenly he’s got a significant herd and he’s lending it to them so that they can have their ceremonies. And Quanah is helping convince TR, and TR creates a refuge where Quanah’s people are more or less in the Wichita Mountains, where the Kiowa, a different tribe, believe all the buffalo came out of the Earth. But there are no buffalo to put in this new refuge. So where do we get ’em from? The Bronx Zoo! I mean, you cannot make this up.

William T. Hornaday, who remains a white supremacist, probably a eugenicist, is a taxidermist. He wants to save the buffalo, and he’s the creator of the National Zoo and the Bronx Zoo. You’ve got a lot of people who are making journeys — Buffalo Bill Cody, Buffalo Jones. These are killers of buffalo, and then they’re savers of buffalo. I just love the fact that people evolve. Sometimes we fix people where they are and forget that the real story is about development, character development, the war within us, between our good and our bad sides.

I mean, that’s what the Greeks are saying with heroism. Heroism isn’t perfection. We always say, “Oh, there are no heroes today.” It’s just bulls—. They’re everywhere. The Greeks used the gods, the boldface names, to tell us about the negotiation, the war within people between their great strengths and weaknesses. Achilles has his heel and his hubris to go along with his great strength. That’s what it’s about. We have a sign in the editing room that says, “It’s complicated.” They’re not just one-dimensional figures.

I think to love history and not just cherry-pick it to use as a bludgeon, you have to love complexity.

No question. You have to yield to it. You can’t just say, “I’m going to use this story to make my point of view.” Richard Powers, the novelist, said: “The best arguments in the world won’t change a single person’s point of view. The only thing that can do that is a good story.” Once the story is told and out there, it’s up to the person who receives it. Is it a transformational thing? Is it at the edges? Yeah, probably. That’s where most change takes place.

The film is full of memorable stories and details — I think of the nobleman who came to America to kill thousands of animals, that perhaps psychopathic level of blood lust — but what thing did you learn that jumped out at you, that you couldn’t shake?

The thing that comes to mind is Germaine White at the beginning of the film, talking about 600 generations of Indigenous people interacting with buffalo. She says, if you put that timeline on a clock, Columbus is at 11:28 p.m. and Lewis and Clark are a quarter to midnight. And that does remind me to have some humility about it. We’ve got no experience here. The Native peoples have lots of experience.

And then there’s the Indian head nickel, which has got a buffalo on the back. The buffalo they modeled it after was sent to the meat-packing district in Manhattan and parceled out. We’d already begun to romanticize, to fetishize, two groups — Native Americans and the buffalo — that we spent the last hundred years trying to exterminate. And suddenly, they’re the symbol of us. It shows a prick of conscience, but at the same time, it’s sort of obscene. And George Horse Capture Jr. says, “I have to ask: Why do you kill the things you love?”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.