- Share via

For Craig McCracken, it was the sight of bootleg piñatas — made in the image of his tiny but mighty heroines — on storefronts across Los Angeles that were the first and most tangible indicator that “The Powerpuff Girls” had attained mainstream cultural relevance.

At the onset, McCracken, now 52, believed his high-octane animated show about three crime-fighting kindergarten girls would at most become a cult hit. Instead, the Cartoon Network Studios production, which celebrates its 25th anniversary this week, has turned into a worldwide pop culture phenomenon since its 1998 premiere.

“The dream of any cartoonist is to create a character that resonates with people and has global popularity. That’s what I always wanted to do,” McCracken said during a recent video interview. “I’ve been very fortunate that the girls reached that level of success.“

To commemorate the landmark occasion, Cartoon Network will run a marathon of the show on Saturday. A new “Powerpuff Girls” AR filter is now available on social media platforms, including TikTok and Instagram, and a collection of apparel and homeware will debut on Warner Bros. Discovery’s online shop.

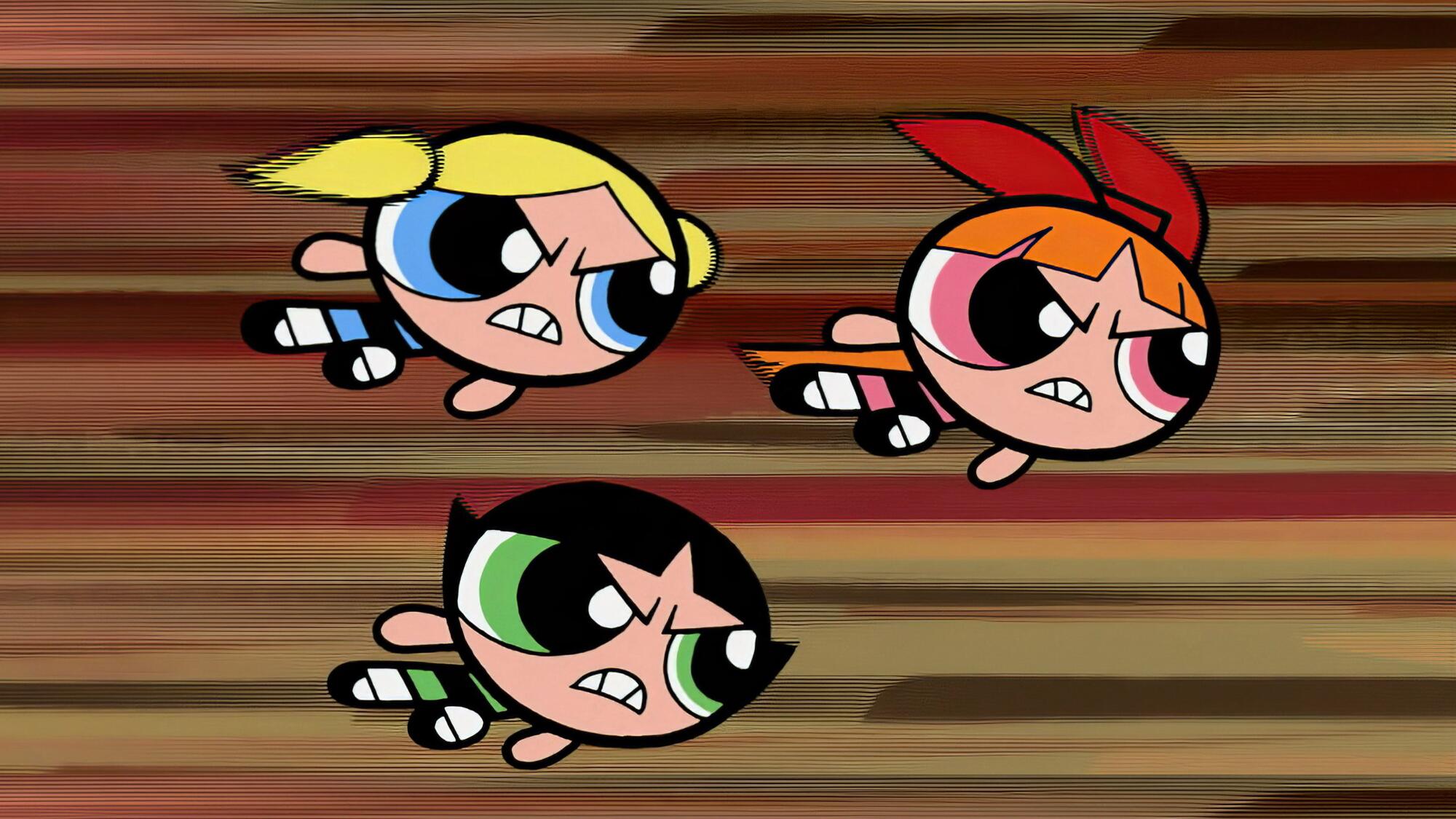

Part of the enduring appeal of Bubbles, Blossom and Buttercup lies in the dissonance between their adorable appearance and their ruthlessly tough superhuman feats.

“You’ve got this colorful, cartoon-y, rainbow-y show with cute characters and then this really hardcore violence,” said McCracken. “That balance is what makes the show funny. If they were drawn more anime or more realistic, I don’t know if the show would feel as fun.”

McCracken said he believes young girls growing up drew great empowerment from seeing not only how clever and strong the Powerpuff Girls were, but that they were appreciated and embraced in Townsville for their contributions. “That’s the way things should be,” he said.

In 1991, years before “Powerpuff Girls” debuted on Cartoon Network on Nov. 18, 1998, McCracken conceived the trio while studying at CalArts. Known as “The Whoopass Girls” back then, the concept emerged as a superhero parody inspired by his love of the 1960s “Batman” show starring Adam West.

“You’re used to seeing big, strong muscle guys fly around and beat up monsters, but not cute little girls,” he said. “That contrast excited me. I started developing it from that point.”

“You’ve got this colorful, cartoon-y, rainbow-y show with cute characters and then this really hardcore violence. That balance is what makes the show funny.”

— Craig McCracken, creator of “The Powerpuff Girls”

By the time he was working at Cartoon Network and had the chance to make shorts with the characters in 1995, McCracken was so invested in their world that he said he made the mistake of alienating potential audiences by creating these samples as if the show had been on the air for years. There was a lack of context about who the girls were.

Those “Powerpuff” pilot shorts were part of the “What a Cartoon!” showcase that served as a testing ground for the concepts that would become some of Cartoon Network’s most popular shows in its early days, such as “Dexter’s Laboratory,” “Johnny Bravo,” and “Cow and Chicken.”

When the network screened one of two pilots, titled “Meat Fuzzy Lumkins,” for a focus group of 11-year-old boys, the young tastemakers strongly rejected it. “They said, ‘This is the worst cartoon that was ever made, and whoever made it should be fired,’” McCracken recalled. “I was like, ‘Oh well, there goes my whole career. I’m not going to get to make cartoons for a living.’”

The show didn’t get picked up then, but McCracken’s work as a storyboard artist on “Dexter’s Laboratory” caught the attention of Linda Simensky, former senior vice president of original animation at Cartoon Network Studios, who became his champion.

Based on her gut feeling about McCracken’s talent, Simensky, the unsung heroine in the story of “The Powerpuff Girls,” persuaded Mike Lazzo, then the executive in charge of programming, to let McCracken take another stab at the show in order to keep the crew working with Genndy Tartakovsky on “Dexter’s Laboratory” together at the studio.

“If I had been maybe older, a little more mature, a little less daring, I might not have done that, but I was taking my direction from a different place than logic,” Simensky said. “I was just going into it thinking, ‘Craig’s really funny, this is bound to work.’ And then it did.“

With Simensky’s encouragement, McCracken created a detailed show bible, where he included a series of questions followed by answers from each of the girls to denote their distinct personalities. Eventually the network agreed to make 13 episodes.

“Craig had a really unique sensibility,” said Simensky. “He combined a lot of unexpected references and sources together to get a really unique show.”

“You’re used to seeing big, strong muscle guys fly around and beat up monsters, but not cute little girls.”

— Craig McCracken, creator of “The Powerpuff Girls”

Without hesitation, Simensky said “Bubbles” when asked if one of the girls was her favorite.

“People always underestimated Bubbles, but she could be hardcore when she wanted to be. You expected the other two to always get it right,” she said. “But you didn’t always have the sense that it would work out for Bubbles, but then it did. I found myself relating to her.”

On the day the show premiered, McCracken remembered being in Cartoon Network’s offices in Sherman Oaks (the studio recently vacated it), plowing away at subsequent episodes of the endearing action-packed saga. He recalled Lazzo and Simensky telling him to get a copy of LA Weekly in which a writer had called “Powerpuff Girls” a “perfect show.”

Of the 78 episodes in the six seasons of the original series, which ran until 2005, McCracken believes two of them encapsulate the show’s themes. First, “Bubblevicious,” where Bubbles decides she doesn’t like being perceived as the sweet one and aims to become hardcore. This storyline embodies the lovable yet gritty quality of the girls.

“Beat Your Greens,” in which the girls must eat broccoli aliens to stop their malevolent ambitions, is a response to how McCracken and his team approached common dilemmas that affect children but filtered through the perspective of superheroes. Like plenty of kids, they don’t want to eat their vegetables, but they must for the sake of their city and its residents.

“Their kryptonite is that they have to go to bed, they have to go to school, they have to brush their teeth, they have to listen to their dad, but then they can also save the world. Kids really related to that,” McCracken explained. “They’re saving the day before bedtime.”

Then there’s “See Me, Feel Me, Gnomey,” which never aired in the U.S. because Cartoon Network Studios tried to preempt controversy. The executives believed the team had included images making controversial religious and political statements: In one scene, there are several buildings destroyed in Townsville, and somebody claimed the girders were drawn to resemble crosses. They weren’t. The episode plays out like a rock opera in the style of “Jesus Christ Superstar” and centers around a villainous gnome. McCracken recalled that they unsuccessfully tried to cast Jack Black to voice the part. The once-banned episode can now be found streaming on Netflix.

“People always underestimated Bubbles, but she could be hardcore when she wanted to be.”

— Linda Simensky, a former senior vice president at Cartoon Network Studios

Not unlike a father who is unwilling to pick a favorite child, McCracken can’t choose one girl.

“The girls represent body, mind and spirit. Together they make a whole person,” he said. “They always play off each other. If you remove one the balance is off. When writing them, I’m thinking about what Blossom would say and I immediately go, ‘Bubbles would react this way and Buttercup would do this.’ They function as a single character to me.”

Simensky recalled that while the ratings for “Powerpuff Girls” were no larger than those of other Cartoon Network shows at the time, the interest from companies to license the property for merchandising purposes is what set it apart.

The show’s early popularity prompted the production of “The Powerpuff Girls Movie,” expeditiously completed in just under two years, which reveals villainous Mojo Jojo’s involvement in the origin story of the three vivacious do-gooders.

Once upon a time, just as American skies were being cluttered with TV signals, there was a cartoon factory called United Productions of America.

“‘Powerpuff‘ was doing well in consumer products, and it seemed like the natural next step was to take it to a feature film,” said Brian A. Miller, former senior vice president and general manager of Cartoon Network Studios. “We didn’t have anything else at that point that was doing that well on the consumer product side.”

McCracken, who also wrote and directed the film, remembers hearing rumblings that actor Sandra Bullock was a fan of the show and was interested in voicing one of the characters in the movie. But even if those conversations had become serious, he said he would have rather invented a new character before dismissing anyone in the original voice cast.

“Warner also wanted Craig to use famous pop songs in the movie, and Craig refused. He really felt it was not a fit for what he was doing,” recalled Miller. “I admired him for that.”

The 73-minute movie, released on July 3, 2002 — the same weekend as “Men in Black II” and “Like Mike” — only grossed $16.4 million worldwide during its theatrical run, a disappointing figure given its estimated $11 million budget.

“The movie industry is very different than the television industry. I walked into it a little naive thinking, ‘I’ll just make a long episode,’ and I don’t know if that was really the right approach. I hadn’t made anything that long before,” McCracken said. “Tonally the movie may also be a little too dark. We lost a little bit of the bright fun of the show in doing that.”

“It was a pretty intense movie,” said Simensky. “They were thinking ‘Akira’ as they were making that movie: ‘There’s got to be a battle royale and this has to be spectacular.’”

The production later discovered one key reason for the movie’s unsatisfactory numbers was that boys who watched the show didn’t want to go to the movie theater to see what might have been considered a movie for girls. “A lot of them wanted to see it but didn’t go because they thought that if their friends saw them, they were going to get picked on at school,” McCracken said. “If there was a movie now, I think boys would go see it.”

Simensky recalled another focus group where they asked boys between 8 and 9 years old if they watched “Powerpuff.” Only one of them raised his hand. Later, they told them to put their head down and close their eyes and asked them again who watched the show. This time, the vast majority admitted to watching it when the others couldn’t judge them.

“The funny thing was girls watched it, but probably not in as big numbers as boys did. Girls bought the merchandise, boys didn’t. Here is a show that was defying logic,” she said. “That’s an unusual situation. People in TV know better than to get into that situation now.”

Back in 2016, a decade after the end of the original show’s run, Cartoon Network rebooted “Powerpuff Girls” without McCracken’s involvement and with an entirely new voice cast. At the time McCracken was working on the show “Wander Over Yonder” for Disney Television Animation. Developed by Nick Jennings and Bob Boyle, this version of “Powerpuff,” he thinks, flipped his concept on its head, making it lose its core appeal.

Sugar, spice, everything nice and an accidental dash of “Chemical X.”

“We were first and foremost making a superhero show, but they happened to be kids who then happened to be little girls,” he said. “What they were doing was making a show about little girls who had superpowers. Because the focus changed, the tone changed.”

McCracken felt similarly about the now-canned attempt at translating his animated show into a live-action CW program. From what he saw, it seemed as if the studio just planned to smack the “Powerpuff” label on a generic superhero narrative for branding purposes.

“I had one meeting with them and I told them, ‘When you turn them into adults, they’re no longer the Powerpuff Girls because if they’re adults, that’s just three super girls who don’t have to deal with being kids,’” McCracken recalled. “That’s a completely different show.”

Thankfully, there’s renewed hope for the characters to be revived. McCracken is developing a new “Powerpuff Girls” project with Hanna-Barbera Studios Europe, as well as a preschool spinoff of one of his other shows, “Foster’s Home for Imaginary Friends.”

McCracken was not a father when he worked on the original series. But now that he has a young daughter, he appreciates the opportunity to see “Powerpuff” through her eyes.

“I remember when my daughter was 4, she saw the girls around the house and wanted to see what it was,” McCracken said. “We played her the main title and she immediately went, ‘They’re superheroes, but they’re kids.’ That just blew her mind.”

Raised by a single mother, McCracken hopes his strong little women have had a positive impact.

“I’m happy that I could bring a show like this into this world, even for me as a dad and for my daughter who can see, ‘Hey, these girls are powerful and tough,” he said.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.