The naked guy at graduation is just one of Steven Lavine’s memories from 29 years of running CalArts

- Share via

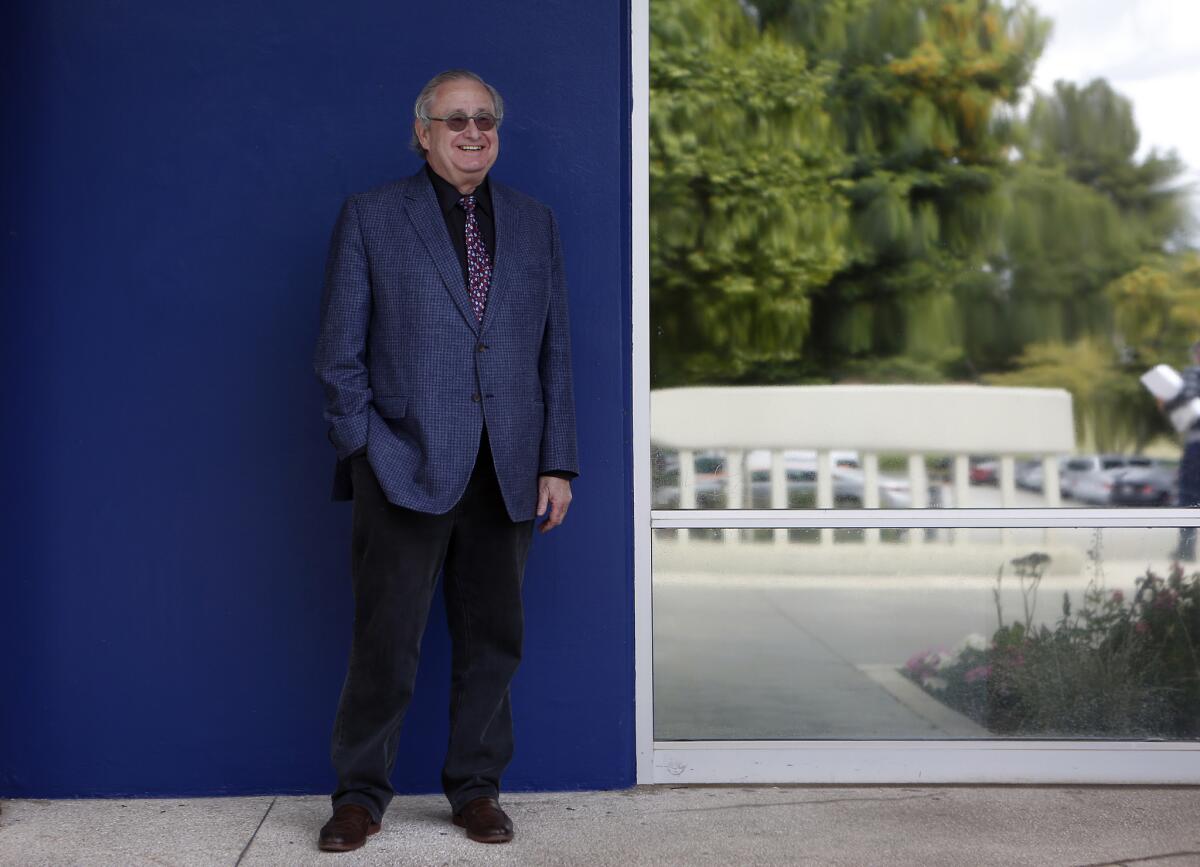

The paintings have been removed from the walls and the desktop photos have been wrapped and put away. Strewn around the room, odds and ends await boxing: a gong and assorted piles of books. After 29 years, Steven Lavine, the third president of the California Institute of the Arts, is retiring. This month, he attended his last CalArts graduation.

“After handing out degrees for 28 years,” he says with wistful smile, “I was given an honorary degree as well.”

Over the course of his long tenure, Lavine has faced triumph and devastation.

When he took the reins at CalArts in 1988, the school — the experimental arts outpost located on the northern fringes of Los Angeles — was in danger of going bankrupt. In 1994, the Northridge earthquake rendered the campus uninhabitable. But Lavine piloted the school through those stormy waters, and today CalArts is thriving, with an endowment of $152 million and a ranking that places it among the top 10 fine arts schools in the country, according to U.S. News & World Report.

At the end of this month, he will hand the reins to his successor, Ravi Rajan, after which he will serve as founding director at the Thomas Mann House, a new center in the writer’s former Pacific Palisades home that will host scholars and journalists.

In the midst of packing, Lavine took time to chat about his years at CalArts. He is low-key and unhurried. On several occasions, he refers to “we” rather than “I” — an acknowledgement of the contributions of his wife, artist and writer Janet Sternburg. Without her, he notes, “I couldn’t have done this.”

In this edited oral history, he reminisces how he battled deficits, rebuilt a shaken campus, opened a downtown performance outpost and contended with the student who showed up at graduation wearing nothing but a snake.

Mid-1980s

Getting the job

When CalArts approached Lavine, he was a mid-level foundation officer who had taught literature for a spell at the

When I’d seen the ad for the job, I thought, “There’s not a chance in the world.”

I’d never really administered anything. They did this initial search and the finalists were mostly business people. But at the last minute they decided that CalArts’ problems weren’t going to be solved on business grounds alone. You had to have critical understanding of the substance.

They called Martin Friedman, [the director] at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. I’d done grant work for them. He gave them my name and after that things went very quickly. I remember Harrison Price, one of the trustees — his nickname was “Buzz.” He did the original feasibility study for Disneyland and for CalArts. He said, “You’re the kind of guy I’d want to go to a movie with, but I don’t think you’re tough enough.”

My answer was, “I don’t think I’m tough enough either.” But mostly what you do at a foundation is find nice ways to say “no.” I was very good at saying no. That was the basis for being tough.

They took this very real chance and gave me the job.

Inauguration Day, 1988

An unforgettable induction

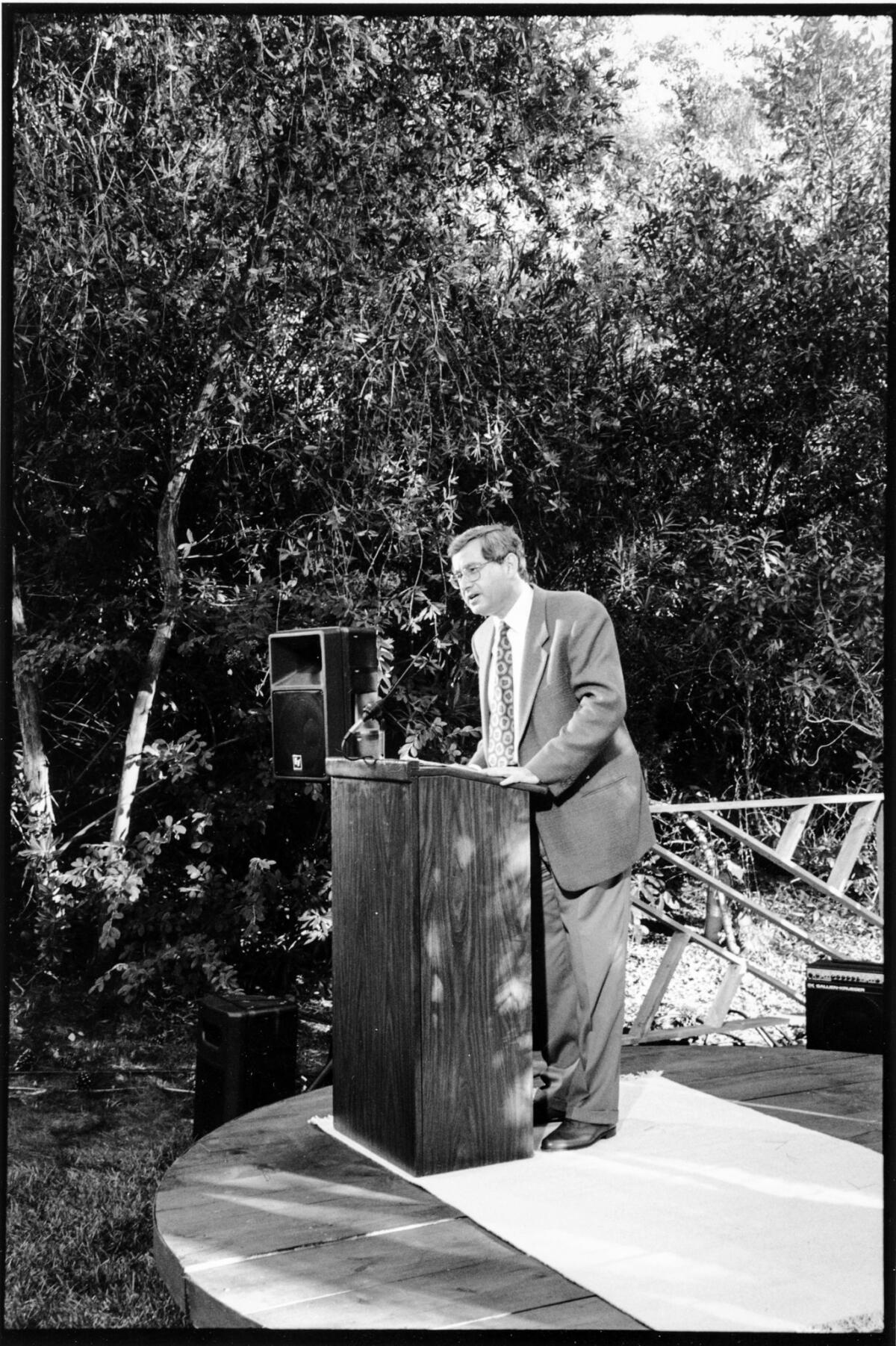

Lavine was inaugurated as president in a Santa Monica ceremony that featured Javanese gamelans and African drummers.

[Playwright] James Lapine got [singer and actress] Cleo Laine to sing songs from “Into the Woods.” [Composer] Mel Powell, who had been the dean of the music school, performed a piece of his. Then [choreographer] Trisha Brown, who was a friend, she came out and did a performance. We did all this [at the

But we didn’t know they didn’t have their conditional use permit. The police arrived and we learned that it was illegal to do music on the street in Santa Monica. My assistant was holding the police off at the door saying, “That’s Mayor Tom Bradley. Do you really want to close off an event with Mayor Bradley?”

They let us go ’til midnight.

The Early Days

A close call with bankruptcy

The good times pretty much ended with Lavine’s inauguration. When he took over, the school’s deficit was budgeted at $1.8 million out of a budget of $16 million — more than 10% of the total budget.

And it was going up each year by a few more thousand dollars. We had a small endowment that was being drawn to pay this. So I asked the vice president to do the financials to look at how long we had before we really were bankrupt. He said we had about three years before we were broke and couldn’t pay the bills. The deans had been struggling to hold it together without being able to give inflationary raises to their faculty. They were operating on will power — and they were fighting between themselves.

Every day was a trial. There were all of these petitions saying, “You should resign.” I remember at 4 in the morning, [Janet and I] talking about how long do we have to stay? We agreed we had to stay until there was a balanced budget. We figured it would take four years. In the end, it took five. We built a plan on more fundraising and increasing the size of the student body. And I didn’t fire anybody.

1993

Toasting success

By the end of 1993, the school’s financial problems had turned around.

We were back to a balanced budget. We were no longer shouting at each other. Enrollment was growing. More of our alums were maturing and getting successful. There was more we could brag about. On New Year’s Eve, going into ’94, my wife and I toasted one another. CalArts was artistically, educationally and economically safe.

And then, Northridge.

1994

The Northridge Earthquake

On Jan. 17, 1994, a magnitude 6.7 earthquake struck Los Angeles, toppling freeways and apartment buildings and killing more than 70 people — devastating CalArts.

Everything fell that could fall of the main building — and CalArts was really the main building and two dorms. The concrete block, out of which the building was made, was cracked. I believe there was 42,000 linear feet of cracks. The building was not stable.

Initially, we set up 16 party tents and each school would choose a teacher to meet with students while the others figured out how to have a curriculum. We had to find a way to stay open. We had just gotten the budget balanced. If we had to return tuition for the semester, we’d go out of business.

The thing we needed first was space. I called

It turns out there was this

We had this [campus-wide] meeting on the front steps of [CalArts] because we couldn’t go inside. I remember telling [everyone], “We are going to go on. For those of you who stay, this will be the most important semester in your life. It will prove that you can make art no matter what happens.”

The 1990s

Rebirth: Too vital to disappear

The school pulled through with Lavine’s guidance and the help of trustees and other supporters who connected the school with resources to recover and rebuild. But though the quake was devastating, surviving it was an important milestone.

It produced a kind of confidence that has been the setting for everything since. The biggest turning point was that the Getty Foundation offered us a $2-million grant we didn’t ask for as working capital toward rebuilding CalArts. It was recognizing us as a vital Los Angeles institution. That was the moment where we recognized we had crossed a line. The people who really knew something were saying, “We can’t let CalArts disappear.”

2003

REDCAT debuts

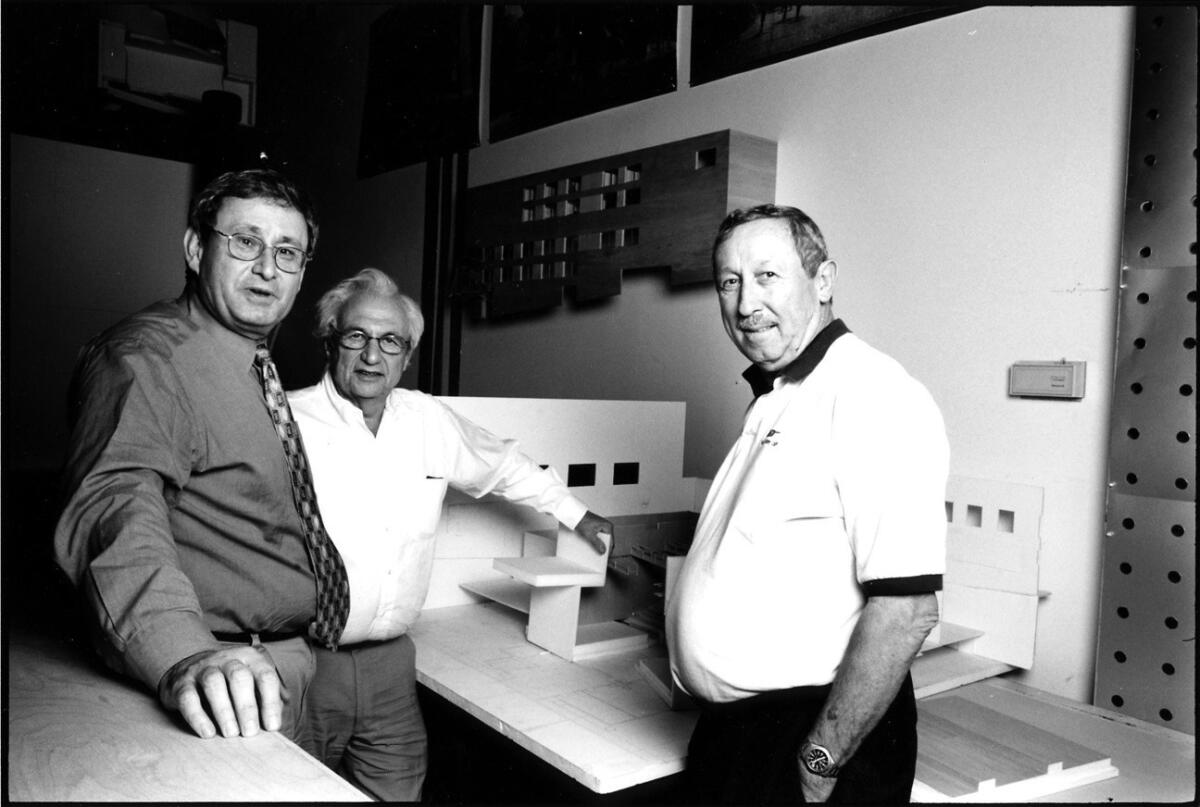

Less than a decade later, CalArts launched a new performance space in downtown L.A. The Walt Disney Co. had made a large donation for the construction of the Gehry-designed Walt Disney Concert Hall. As part of the deal, CalArts got a space under the southwest corner of the building to put on works of dance, theater and cinema. In 2003, REDCAT — short for the Roy and Edna Disney CalArts Theater — opened its doors.

Our first performance was before we even had our formal opening — typical CalArts. [It was] a Japanese company called Dumb Type. They’re kind of a performance company, somewhere between dance and theater. Our founding director, Mark Murphy, had presented them in Seattle. We saw that we had a chance to bring them to Los Angeles, so we jumped.

One of the challenges the show presented is that it was accompanied by loud industrial sounds. Our deal with the [

Lewis Segal, the [Los Angeles] Times dance critic, he hated it. But [Times classical music critic]

Over the years

On the cutting edge of weird

Over 29 years at CalArts, Lavine has seen experimental concerts, bizarre animation and the legendary art critique sessions run by the late conceptualist Michael Asher (sessions so marathon, they inspired a chapter in journalist Sarah Thornton’s book “Seven Days in the Art World”).

I see a lot of things that on first view seem wacky, but they turn out not to be wacky.

There was a concert once that involved a guy playing tuba underwater. So mostly what you heard was bubbles rising to the top and popping. But it was kind of thrilling. [Asher’s critiques], to look at it, you’re just looking at people sitting there. But he was waiting for people to express their own ideas. It’s this trust in generating stuff yourself. And that is in the spirit of CalArts — the right to create whatever you want.

My favorite thing was from a graduation. There was this guy in the audience who was naked except for a boa constrictor wrapped around him. I was handing out the degrees then. And I’m terrified — terrified — of snakes. So the provost went down and asks the guy if he could leave the boa constrictor behind because the president is going to faint. And the guy said, “I can’t do that. I’d be naked.”

2017

A changed landscape

In his time at CalArts, Lavine has seen Los Angeles evolve as an arts center, and he’s seen art evolve into new forms.

When I came here, the experimental edge of everything — whether it was dance or theater or music — was seen as a small edge of a big world. Now symphonies are defined by it. Every philharmonic wants [a director like] Esa-Pekka Salonen who will do contemporary music. The American Repertory Theatre in Boston is doing immersive performance.

What CalArts was doing as a radical alternative has fed its way into the mainstream. These things weren’t done to convert the mainstream, but they did. The challenge for CalArts is, where next do things have to go?

ALSO

Meet Robin Bell, the artist who projected ‘Pay bribes here’ protest messages onto Trump's D.C. hotel

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.