At LACMA, the horror of 9/11 through the eyes of a Muslim artist who found a different path

- Share via

The evening of Sept. 11, 2001, had been like any other for Abdulnasser Gharem — until it wasn’t.

A self-taught artist and a young officer in the Saudi Arabian army, Gharem was relaxing at home in the city of Khamis Mushait, where he’d grown up with 11 siblings, when the yelling began. “Come here!” “Watch.” “Look at this!” The family anxiously crowded around the living room TV. The images of the World Trade Center collapsing were devastating to watch, the shock matched only by the news that eventually followed: Two of the hijackers were Gharem’s friends from high school.

“I was shocked, how could this be? It was like someone stopped the world for a while. Everything paused,” Gharem says, sitting at an outdoor café at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, where the exhibition “Abdulnasser Gharem: Pause,” recently opened. “We used to roam around the city listening to music. We’d just drive around looking for fun in the car. I thought: ‘We grew up in the same city, in the same environment, we had the same knowledge — it could have been me.’ But we’d taken very different paths.”

Shortly after, Gharem began work on “The Path (Siraat),” a three-minute performative video and subsequent silkscreened photograph of a broken bridge in his hometown with Arabic text spray-painted across the concrete. It read, “The Path,” repeatedly, along a damaged road headed into darkness. Those pieces, like all of Gharem’s work in the LACMA exhibition — his first solo show in the U.S., featuring mixed media stamp paintings, prints, sculptures and film — address the aftermath of the Sept. 11 attacks as well as the artist’s life experiences.

“I’m trying to say what the people couldn’t say in my country,” Gharem says. “It’s hard because the media in all Arab countries has been controlled by the government. So I think the role of the artist is to bring these issues, through the artworks, to the people.”

LACMA curator of Islamic art Linda Komaroff, who organized “Pause,” says that Gharem’s 11 works in the show are groundbreaking in their construction and push boundaries politically.

“It incorporates motifs and artistic ideas that are part of the canon of Islamic art — geometric and floral designs, arabesques and also embedded text — but it’s very contemporary,” Komaroff says. “He’s inventing new media, like with his stamp paintings, and a lot of his ideas are tied to life in Saudi Arabia today. What interests me is this intersection of past and present. He’s totally fearless.”

With his gravelly voice, thick black hair speckled with gray, mirrored sunglasses and chain-smoking of Marlboro Reds, Gharem looks far more the desert soldier than the sensitive artist. In fact, balancing those identities had been a decades-long struggle for Gharem, one that he channeled into his art.

Gharem spent 23 years in the army, eventually being promoted to lieutenant colonel. Before he left the army last year he fought in “war after war,” he says. “They’d throw us into the desert with a bottle of water and [hope] we survive.” Gharem slept in trenches at night and drew in his sketchbook during slips of down time by day. Military life was ordered and unforgiving; the looser, messier intellectual process of making art helped to balance that rigidity and allowed his brain to unfurl.

“It took me a long time to find a way to manage being in the army and being an artist. It was so difficult,” he says. “Being an officer, you have a lot of responsibilities and you have to follow orders. You can’t say no. And when you do your art, you need to be totally free and neutral. Sometimes I felt like a double dealer.”

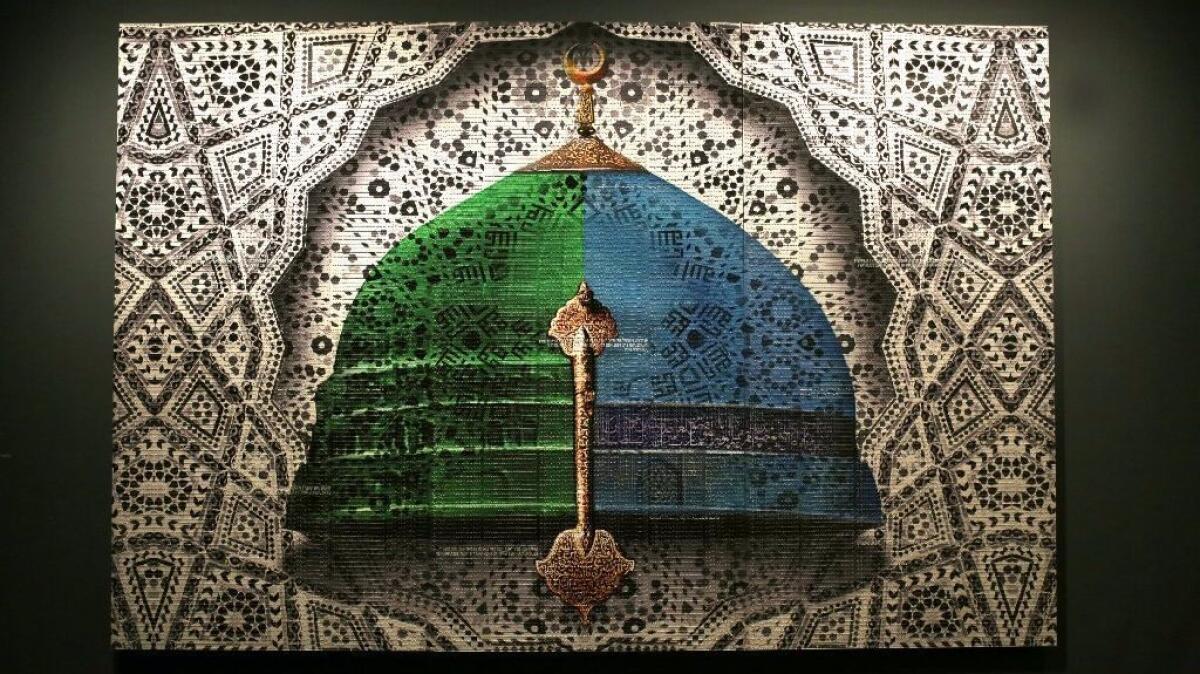

Dichotomies, not surprisingly, factor into the artist’s work. One of his newest pieces, “Hemisphere,” is a 400-pound resin sculpture. One side is the sea green dome of the Mosque of the Prophet in Medina, Saudi Arabia; the other side is an 18th or 19th century Iranian battle helmet. They represent war and peace, as well as the left and right sides of the brain, and also the opposing sides of faith-based religion, with strength, support and compassion on one side, and prejudice, division and violence on the other.

“Through the education program we have, through what they are saying in the mosque, they want to make us like warriors. And we are going to fight,” Gharem says. “Why do you want to create me as a warrior since I was a kid? Who am I going to fight? And suddenly, what you have seen in the Muslim world, the Arab world, is that Muslims are fighting themselves.”

Gharem had hoped to study art at the local university after high school but he wasn’t accepted, he says. During the requisite admissions test, prospective students were asked to create a piece of art in front of their exam auditor. Gharem drew a portrait of his interviewer, a religious Muslim, forgetting that the predominant interpretation of Islam taught in his area at that time prohibited depicting the human form.

He entered the military academy instead. And he continued making art when off duty, back home in Khamis Mushait. But there were few — if any, he says — art galleries and exhibition spaces in Saudi Arabia in the early 2000s. In 2003, Gharem co-founded the artists collective Edge of Arabia with his friends Ahmed Mater and Stephen Stapleton. It aimed to spur the creation of new contemporary art in the area and organize exhibitions at home and in the West.

“We wanted to build a bridge,” Gharem says. “Because if you’re going to wait for someone to do it, no one is going to do it. It was like a dream in the beginning. We never thought it would happen. We became like the avant-garde.”

In 2010, LACMA Director Michael Govan traveled to Saudi Arabia, where he saw Gharem’s work in an Edge of Arabia exhibition. After returning to L.A., Govan showed the work to Komaroff, who purchased “The Path” film for LACMA, which has the largest collection of contemporary Islamic art of any museum in the U.S.

The collective, which exhibited work in the 2009 Venice Biennale and 2010 Berlin Biennale, has been a game-changer in Saudi Arabia, sparking the contemporary art scene there, Komaroff says.

“Edge of Arabia basically invented contemporary Saudi art,” Komaroff says. “There may have been artists here and there, and mostly working outside the country, but it didn’t exist as a concept. Even the idea of a man being an artist in Saudi Arabia then wasn’t something people entertained. They brought together whoever considered themselves artists. It’s been transformative, especially for younger Saudis.”

Still, life in Saudi Arabia, particularly in the military, Gharem says, was a world populated with procedures, protocol and the omnipresent rustle and thump of bureaucratic paperwork — “rejected,” “accepted,” “check paid,” he says.

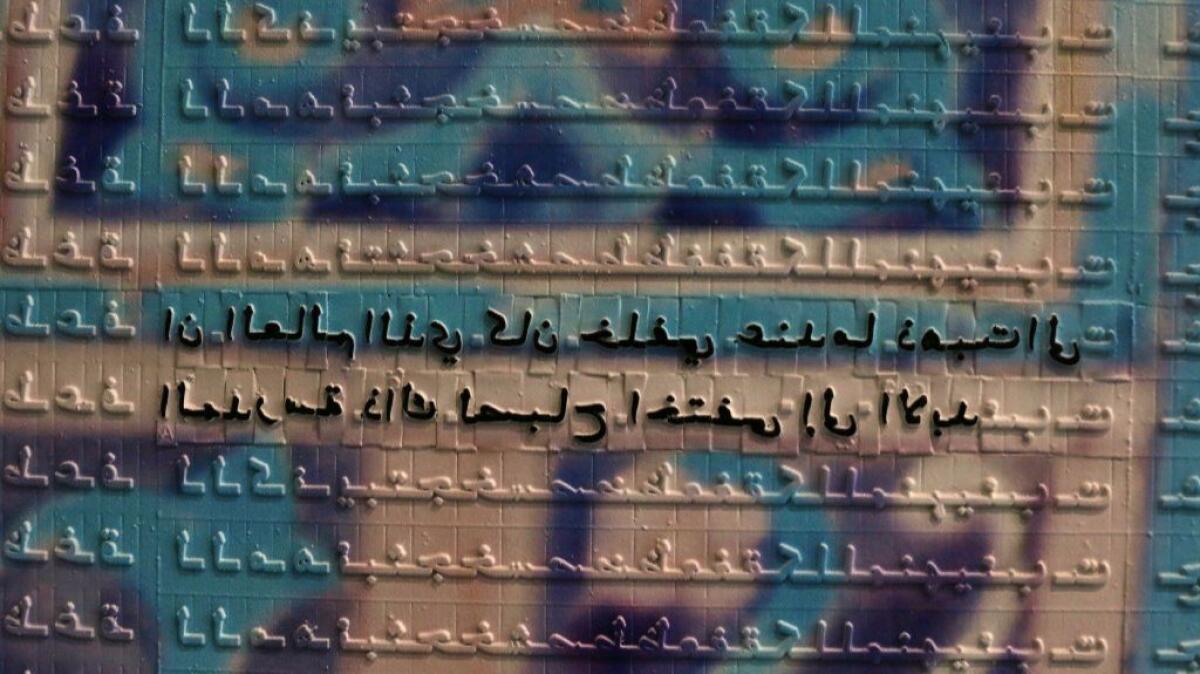

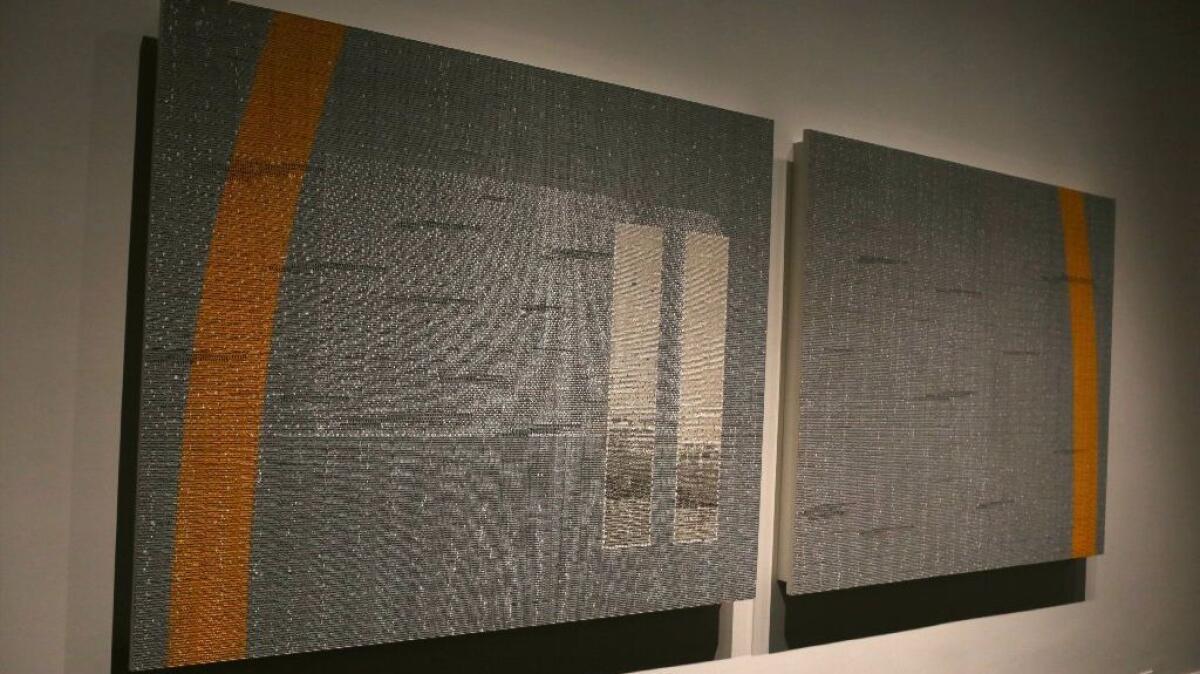

Which is why so much of Gharem’s work is brimming with stamps — as a subject and as a material to construct his art. His stamp paintings, as he calls them, feature a textured, bumpy canvas made up of rubber stamps. Gharem disassembles the individual lettering, paints tiny English or Arabic characters different colors, and then he and his studio assistants reconfigure the letters on the canvas with tweezers. He then digitally prints and hand paints on that work.

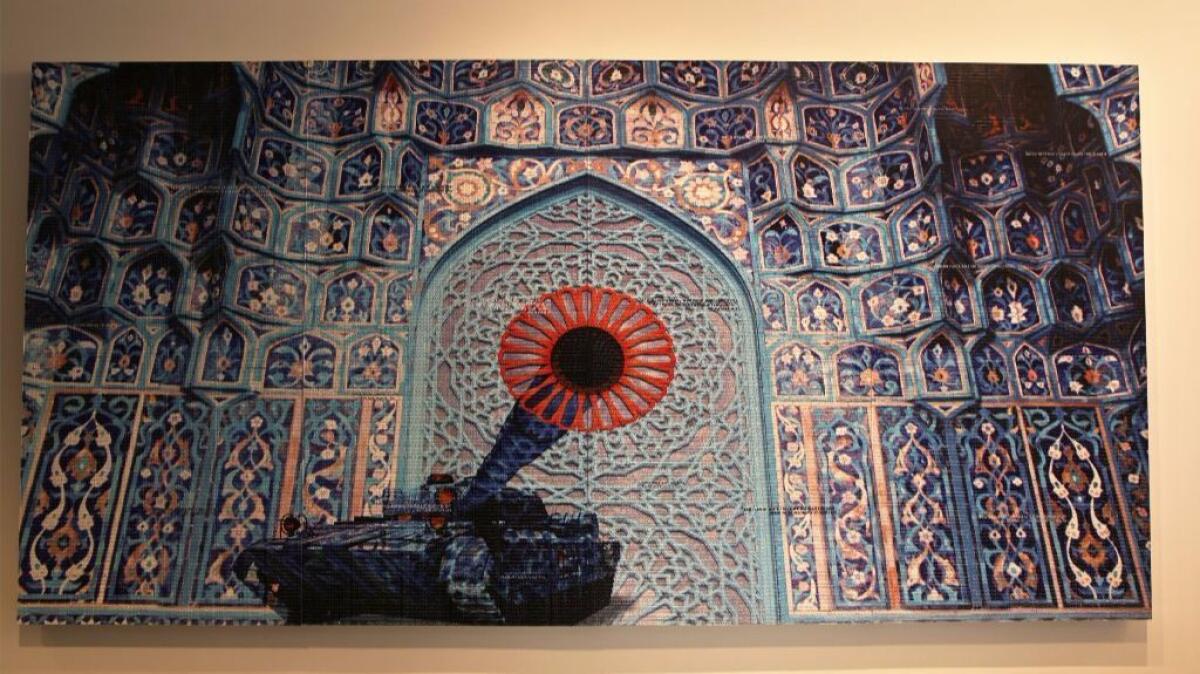

One 2017 work, “Camouflage,” show an army tank, with a bright orange daisy planted in its cannon, in front of a colorful Iranian mosque. It’s brimming with hidden messages, which read backward as stamp lettering does, that speak to war-hungry governments, arms deals and sectarianism, Gharem says, adding that his favorite hidden message in the painting is, “It may be that idealism requires naiveté to survive.”

A 2016 stamp painting, “Pause,” speaks quite graphically to terrorism. It depicts the World Trade Center engulfed in a plume of smoke formed by hundreds of tiny English and Arabic letters and computer keyboard symbols such as @ or # that Gharem painted white and gray and beige and black. From afar, the vertical stacks of the Twin Towers form the digital symbol for pause, as it would appear on a TV remote.

“The world was going crazy and I wanted people to calm down and think about themselves and their ideas and what happened — just stop and think,” he says.

As an Arab and a practicing Muslim, the idea of “The Path” is something Gharem still thinks about daily — how to forge his own path in life and what that might look like, the divergent paths he and high school friends took or the path of Islam itself, in which “God guides us to the straight path like 100 times a day when we pray,” he says.

Ultimately, however, the path should be a personal and pliable journey open to interpretation rather than a rubber-stamped road, Gharem says — an overarching theme in his work. Is the path something one can see and choose to follow, or is it something that one blindly follows and leaves behind? The answer, he says, is both. Or neither.

“It’s up to the people, they will just see it,” he says. “That’s what I’m trying to do, is to change the definition of the path itself.”

A CLOSER LOOK: Deconstructing Abdulnasser Gharem’s massive stamp painting “Camouflage” »

Follow me on Twitter: @debvankin

ALSO

Beverly Center as art gallery? How some big-name artists are behind those construction barricades

The exhibition that has art fans in a fury: Our critic’s take on MOCA’s Carl Andre retrospective

A groundbreaking show to confront the gender bias in art: ‘Women of Abstract Expressionism’

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.