Review: Getty Villa’s ‘Buried by Vesuvius’ is exquisite and, at times, explicit

- Share via

When Mt. Vesuvius blew its top in AD 79, the now-fabled volcanic eruption began a winding sequence of events that, exactly 1,900 years later, heralded the emergence of Los Angeles as an international artistic dynamo.

Who could have imagined?

In 1979, confirmation came that the J. Paul Getty Museum, a sleepy cultural outpost overlooking the Pacific Ocean at the edge of Malibu, would indeed become the wealthiest art museum in the known universe. Getty died in 1976, but it took three years to settle the will of a man reputed to be the wealthiest American. The elaborate design of the somewhat dull institution, then with a spotty collection of antiquities, paintings and furniture and almost no notable program, is a replica of a lavish villa in Herculaneum buried beneath the lava.

The imposing Villa dei Papiri, so-called because it housed an enormous library of more than a thousand papyrus scrolls, is today thought to have been the extravagant seaside getaway of Julius Caesar’s father-in-law. Together with Pompeii, Herculaneum was the most significant of more than half a dozen ancient Roman resort towns along the Bay of Naples.

The lava that destroyed them also preserved them.

When the $17-million Getty Villa had its debut five years before public confirmation of its $700-million windfall — the Getty Trust’s endowment is now almost 10 times as large — writer Joan Didion noted that “something about the place embarrasses people.” Lesser literary lights than she ascribed the Malibu villa’s ostentation to its Hollywood proximity, as if something contagiously rotten about nouveau riche L.A. permeated the local atmosphere.

But it wasn’t just the vulgarity of a huge classical beach house decorated in pink, blue and gold that prompted airy dismissals as being “garish” and “backlot.” Didion knew better. Didion knew that Rome’s empire wasn’t exactly a tasteful place of pristine virtue.

The billionaire’s improvisational copy of a brash ancient villa made a profoundly political statement, telling visitors in no uncertain terms that, as she put it, “we were never any better than we are and will never be any better than we were.”

Didion was right. For irrefutable evidence, go see the Getty Villa’s remarkable new exhibition.

“Buried by Vesuvius: The Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum,” deftly organized by antiquities curator Kenneth Lapatin, presents 34 sculptures in marble or bronze excavated at the Italian site, some shortly after it was discovered in the 1750s and some only in the last 20 years. Deadly poison gases trapped in the ancient eruption were a primary reason archaeological digging was suspended late in the 18th century; modern excavation techniques revived the search in the 1990s.

They dug up some incredible stuff.

The elaborate complex’s floor plan was drawn by Karl Jacob Weber, a Swiss engineer who supervised the first excavations; it became the Getty Villa’s template. Weber also helpfully recorded the locations where many of the sculptures were found. (The Villa dei Papiri held the largest ancient sculpture collection yet recovered from a single Classical building.) Eighteenth century engravings document several discoveries.

REVIEW: Velázquez paintings are the first of so many reasons to see this San Diego show »

There are also fresco fragments. One shows a ghostly branch of silvery poplar leaves, sacred to Hercules, entwined with gold ribbon and cascading into a room through an open window. Its gaudy architectural setting features oxblood walls, pink pilasters and decorated yellow moldings. The sky is pale blue.

The painted fragment’s luxurious extravagance is underscored by actual bits of a unique tripod, a furnishing that once held a cauldron or bowl. Publicly displayed for the first time, the tripod’s legs are adorned with carved ivory bas-reliefs of cupids cavorting around herms, boundary markers of stone pillars with human heads.

Juxtaposing flirty cupids and boundary herms seems to say: “Pleasure Zone.” And pleasure is what the Villa dei Papiri was about.

That’s pleasure in an Epicurean sense, named for the Greek philosopher.

Epicurus taught that freedom from human anxiety — mortal terrors and a grinding fear of the gods — could be attained through satisfaction of individual desires. Titillation of the senses was essential, but the deepest pleasure came in the calm serenity felt after those senses had been gratified. Tranquility was the aim.

Two extraordinary sculptures that were “buried by Vesuvius” illustrate.

One is an exquisitely carved marble barely 17 inches tall, its subject so shocking to modern sensibilities that, after its was found in 1752, the King of Naples kept it locked in a palace room where it could be viewed only with special permission. The notorious sculpture depicts Pan, rustic god of the wild, copulating with a she-goat.

The entwined marble figures, originally painted, form a masterful composition. Eye to eye, beard to beard, the inter-species lovers regard each other with an intensity both fervent and tender.

Good on the Getty for not flinching at its display. (The curatorial independence that comes with a multibillion-dollar endowment surely helps.) The museum has posted a content warning, and the work sits on an easily avoidable high pedestal in a narrow hallway between galleries.

Explicit art was not scarce in the Roman Empire.

Explicit art was not scarce in the Roman Empire. The flawlessly composed sculpture melds beautiful carving with crude animal craving, the sacred with the profane, posing an age-old philosophical conundrum.

Countless ancient myths report gods shape-shifting into animals for sex with humans. Jupiter ravished Leda as a swan and carried off Ganymede as an eagle. Pan was half-god, half-goat, so animal communion with a demi-god jams the circuits. Perhaps, in an Epicurean sense, the obscene sculpture is a mockery of divinities.

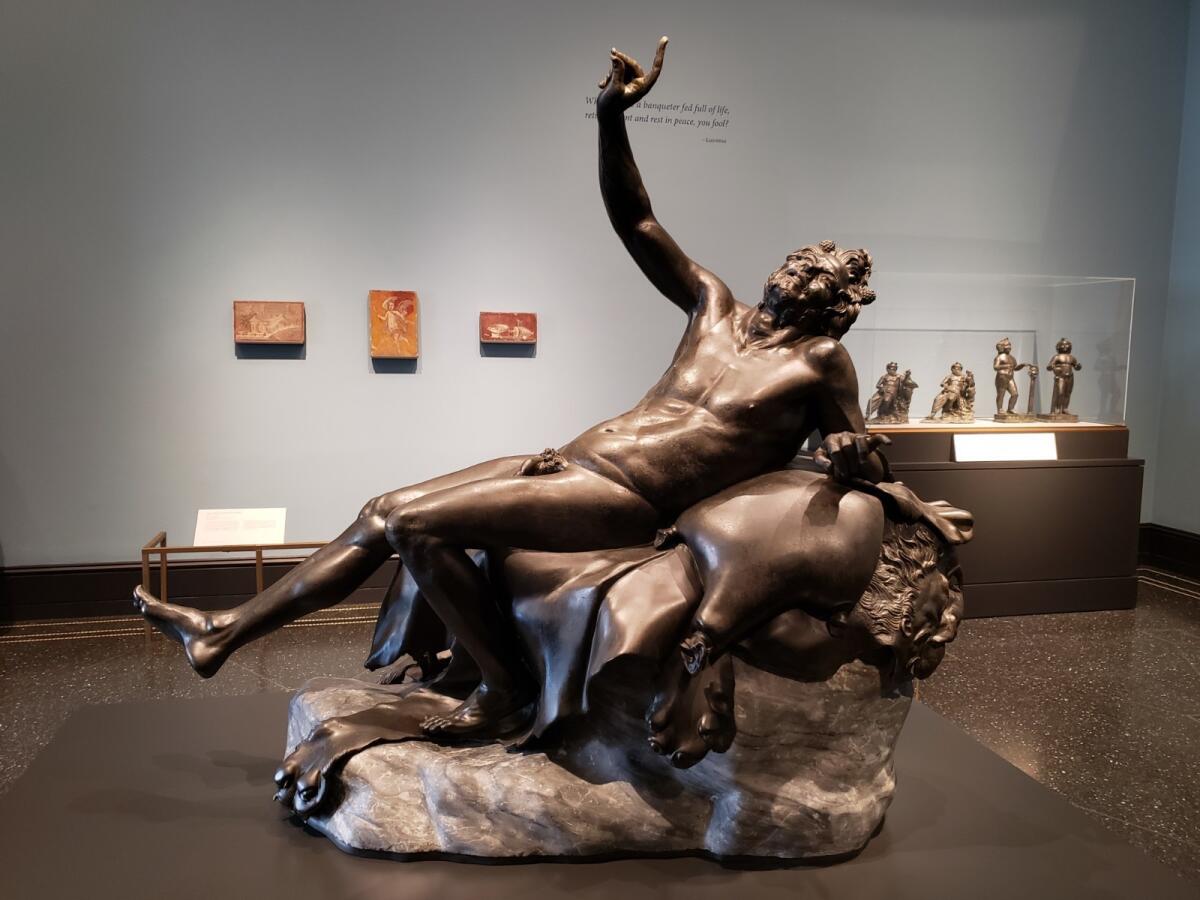

The other exemplary work is a large bronze figure of an elderly drunken satyr sprawled atop a lion pelt and wineskin strewn across a rock. Body soft and flabby, right arm and leg raised and flailing, the satyr tosses back his head in a broad grin.

The sculpture’s stumbling magnificence is located not only in the big bodily gestures but in the marvelously observed details. Take the big toe on his raised foot, which curls upward as if an involuntary effort to maintain balance. The raised hand’s thumb and third digit press together in finger-snapping glee.

This coot is smashed, and he’s having a blast.

The satyr has recently emerged from the Getty’s adept conservation labs. (The rock, pelt and wineskin turn out to be later additions.) It is rare in American museums to see full bronze sculptures from antiquity. Along with an imposing Athena and a breathtakingly elegant woman wearing a gathered sleeveless robe — both expertly carved from marble and just over life size — this show features 25 bronzes.

REVIEW: LACMA’s ‘Art of Korean Writing’ reveals the brilliance in each brushstroke »

Among them are a terrific pair of life-size young athletes poised to begin a footrace; two columnar water nymphs identified as the work of Stephanos, a Greek sculptor in Rome; and a leaping month-old piglet, poised on rear hooves. The plump and innocent animal’s joyful jump is a virtual emblem of Epicurean delight.

If the “Drunken Satyr” looks familiar to seasoned Getty visitors, that’s probably because a modern replica has long sprawled in the museum’s peristyle reflecting pool. No wonder old J. Paul, the building’s late benefactor — five times married and with a dozen prominent mistresses — wrote in his memoir that he saw his oil company as an empire with himself its Caesar. Seeing the original together with other fantastic finds from the Getty Villa’s historical home below Vesuvius is an opportunity not to be missed.

=====

‘Buried by Vesuvius’

Where: Getty Villa, 17985 Pacific Coast Highway, Pacific Palisades

When: Through Oct. 28; closed Tuesdays and Fourth of July

Admission: Free; timed-entry ticket required

Info: (310) 440-7305 getty.edu

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.