Frank Gehry on Disney Hall, what he originally intended — and what it could still be

- Share via

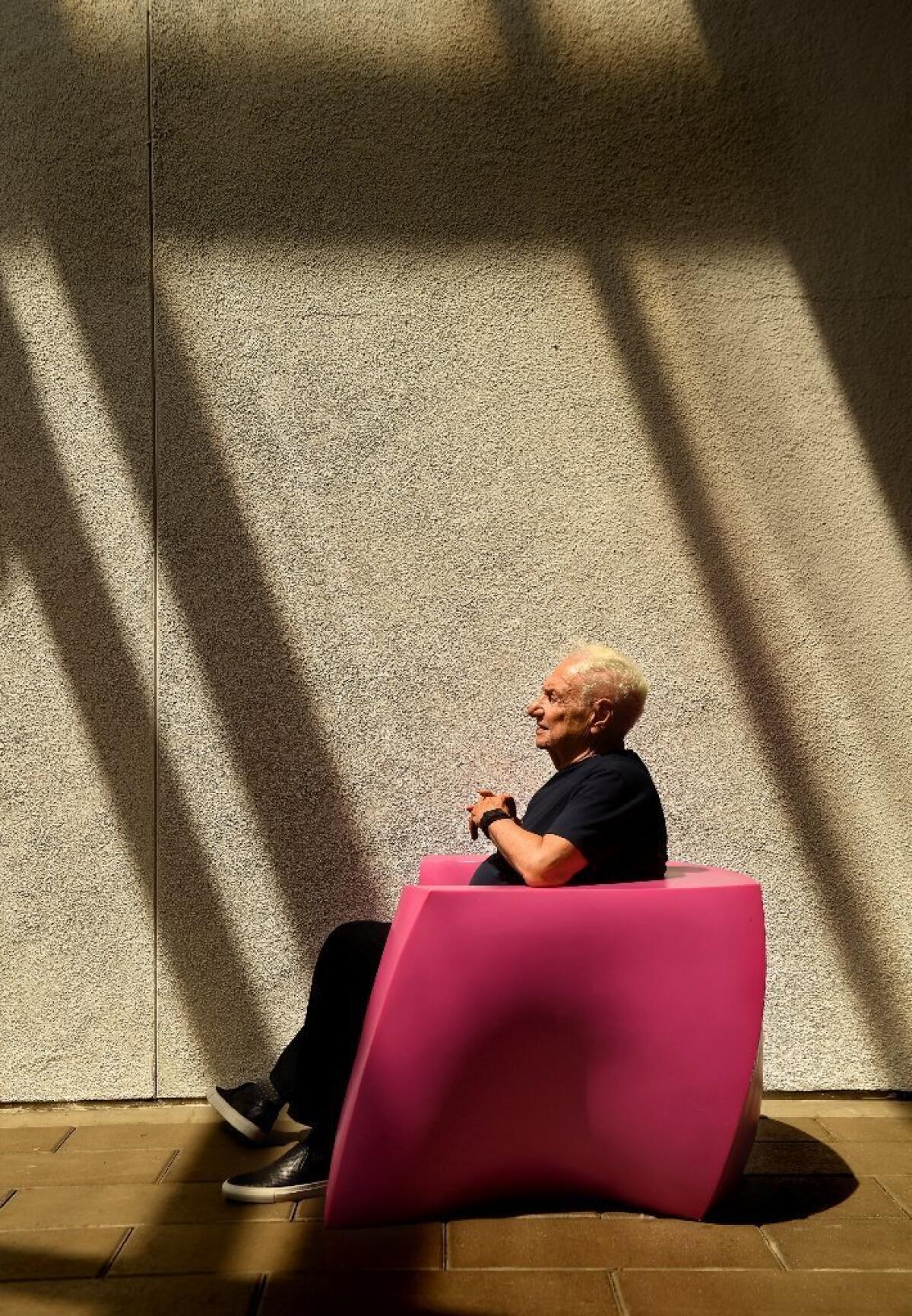

Frank Gehry had never seen Walt Disney Concert Hall from this perspective before, so intimately from above.

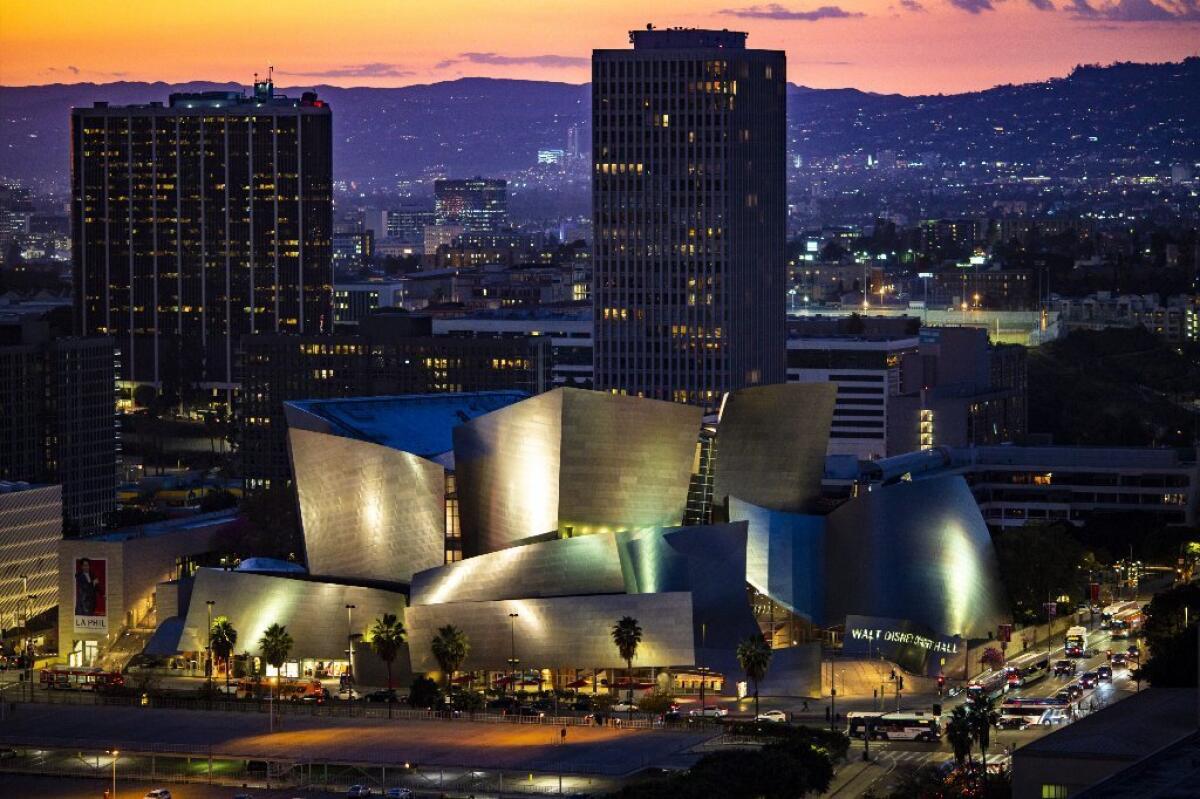

In July, Gehry and his friend Randolph Sherman, an amateur pilot, were flying over downtown Los Angeles in a yellow Stearman biplane, their faces exposed to the wind. It was a warm, nearly cloudless day, and as the small plane tilted its wing and swept over Disney Hall, Gehry’s concert venue looked proud and handsome, backlit in the late afternoon sunlight. From 1,500 feet above, the building’s curvy sheets of brushed steel resembled expanded boat sails billowing in the sea air, the architect says.

Or, maybe a blooming flower.

“I realized: The flower that I promised Lillian I would make was there,” Gehry says of Lillian Disney, who donated $50 million in 1987 for the building that would carry her late husband’s name. (Lillian passed away in 1997, before the completion of the project.) “And she could see it from heaven. I was kind of happy about that.”

That aspect of Disney Hall, which celebrates its 15th anniversary this year, might be just what Lillian Disney had wanted. But the building, considered one of Gehry’s greatest career achievements, is not everything the 89-year-old architect had envisioned.

All these years later, Gehry is still visibly proud of his groundbreaking creation, acoustically one of the finest concert halls of its size in the world and one of the most iconic buildings in Los Angeles, which draws tourists internationally. “We wanted the best hall, the best, best, best whatever we could do,” Gehry says, settled around a Douglas fir plywood conference room table at his Marina del Rey offices.

“And we got it.”

But architecture is a creative collaboration and financial concessions were made when the $274 million building was being erected, Gehry says. For starters, Gehry had intended for the 2,265-seat auditorium to have an orchestra pit, which is important, he says, because during operas staged there, the orchestra “gets in the way.”

“It got value-engineered out, so that has been a stumbling block over the years,” Gehry says of the orchestra pit. “Conductors and composers work together to create contemporary opera, chamber opera, in the concert hall. The orchestra is always in the middle somewhere and it disrupts your vision. They need it now. We built it into the structure, so it’s there, and for two million bucks, they can retrofit the front and put it back in.”

Gehry would also like to see his original lighting design for the exterior of the building reinstated. Early on, he very strategically imagined Disney Hall in stone. Why? “Because stone takes ambient light, street light,” he says. “It’s very subtle and it glows. The stainless steel, if it’s not done right, can look like a cheap refrigerator. And sometimes it does look like that, so I worry about it.”

And don’t even get him started on the cafe, which he originally wanted up front, closer to the Grand Avenue street life. But despite cost-cutting measures “that needed to be made for budget back then,” says Music Center chief operating officer Howard Sherman, “we still have the premiere concert hall in the world.”

L.A. Philharmonic music and artistic director Gustavo Dudamel didn’t say whether or not he wanted the orchestra pit. But the concert hall, he said via email, “is such an inspiration both to me as well as to my L.A. Phil.”

A lifelong lover of classical music, Gehry’s early vision for Disney Hall also included real-time projections of live concerts taking place inside the auditorium onto the building’s facade, so that passersby could enjoy them. In fact, when designing the building, Gehry tested multiple types of steel, he says, settling on the most appropriate surface that was best for projections. Outdoor concert projections take place at Gehry’s New World Center, home of the New World Symphony, in Miami. But it’s a very different experience, he says, in which whole, intact portions of concerts are “wallcast” on a plaster wall that functions as a screen. For Disney Hall, he envisioned projecting snippets of the action on stage – musicians wielding their instruments, Dudamel slicing his conductor batons through the air – each disjointed image appearing on a different panel of the building’s angular surface, like an abstract portrait of sorts set to a classical score.

But it never happened.

“It got shot down,” Gehry says, “because it was thought that was offering people who couldn’t afford it to see it secondhand and that was a demeaning thing. That was brought up by important people in the county.”

We wanted the best hall, the best, best, best whatever we could do.

— Frank Gehry

A version of Gehry’s dream will come to fruition Sept. 27 when, at the end of the L.A. Philharmonic’s centennial season opening night gala concert, Turkish-born artist Refik Anadol will project a media installation onto Disney Hall’s exterior, using the building as his canvas. Anadol has created projections inside Disney Hall before; earlier this year, he brought Robert Schumann’s “Das Paradies und die Peri” to life with abstract 3-D video projections, filling the auditorium with dancing light. For his newest installation, “WDCH Dreams,” Anadol digitized and mined the L.A. Phil’s archives — photographs as well as audio and video from more than 15,000 concerts — and he’ll weave that institutional memory into data-driven patterns illuminating the building’s exterior during nightly performances through Oct. 6.

Gehry says it sounds like a fine idea, but not one he was consulted on. “I have zero to do with that,” he says, shrugging nonchalantly.

Gehry likens his creative process to jazz, a fluid, always-evolving symphony of ideas, as he describes it. A main intention with Disney Hall, he says, was the relationships, or rhythms, between the different entities of people inside the hall, also ever-shifting. “We made a building and we thought about it as a place where people were gonna come to listen to music,” he says. “We thought about the relationship between the audience and the musicians, and musicians to musicians, and how the audience would relate to each other — we spent a lot of time on that topic and fined tuned it so it works.”

When conducting musicians, Dudamel says, the Disney Hall stage is “intimate and precise,” a feeling that extends to the audience. “We feel intimate and so closely connected to our public. Because the audience sits all around us, it’s like being in the middle of a Roman amphitheater and thus we have to play at the top of our game in 360 degrees.”

Gehry was so creatively attached to the Disney Hall project that, even after it opened its doors to the public in 2003, he couldn’t stop mulling ideas. During the orchestra’s inaugural season, former L.A. Philharmonic president Deborah Borda put Gehry’s seat next to hers. Gehry attended weekly when he was in town, watching his and acoustician Yasuhisa Toyota’s visions mingling, and coming to fruition. But even as the orchestra’s music swelled, Gehry couldn’t let go.

“I would say ‘Deborah, why is that light left on over there?’ or ‘Why are these such and such?’” he recalls. “I did it for about three months, and she moved my seat to way back so she didn’t have to listen to me!” (He’s since gotten his seat back.)

I think it’s kept alive classical music, and it’s taken it into the 21st century.

— Frank Gehry

Gehry Partners is situated inside a vast, renovated warehouse filled with bustling employees and rows upon rows of architectural models representing in-progress projects all over the world — France, Israel, Korea. It’s a textural bonanza, a sprawl of maquettes rendered in wood and cardboard and foam, bits of crunchy foil here, a pile of glistening plastic shavings there, the smell of sawdust and glue in the air.

“See this over here?” Gehry says, hovering over a model of Disney Hall, his eyes brightening. He places a tangle of clear Plexiglass slivers, representing a modern sculpture, onto the building’s steps. “I thought: ‘What if we could build a beautiful glass sculpture bar. The steps would go up on either side,” he says, running his fingertips up the itty-bitty stairs to illustrate.

Then he moves blocks of wood around on another model, like a child at play. “See, this is Disney Hall, this is the Broad, this is the Related project and this is the Colburn,” he says. “They could change the paving so you know you’re on something special; figure out something to mark it.”

What Gehry is describing is a veritable village of culture and entertainment that will soon spring to life. Gehry-designed the nearly $1 billion mixed-use complex, The Grand, which real estate developer Related Companies is looking to break ground on in late 2018 or early 2019 directly across the street from Disney Hall. It includes a hotel, a residential tower, an outdoor plaza, a cinema complex and several levels of shops and restaurants. And Gehry is in the early stages of designing two theaters for the Colburn School of performing arts, a 1,100-seat concert hall and a 500-600-seat studio theater for dance and other performances.

“The Colburn, which is a music school, feeds people to the concert hall — you’re creating future musicians,” Gehry says. “The Colburn kids will play in Disney Hall and the L.A. Philharmonic will play in the Colburn. There’s gonna be a cross connection that’s incredible.”

He also recently unveiled designs for the slightly farther away, $14.5-million youth orchestra hall and performance space, the Judith and Thomas L. Beckmen YOLA Center @ Inglewood.

Central to Gehry’s design of the Grand is built-in seating in the outdoor plaza facing Disney Hall, from which one could view live concert projections — finally — on the exterior of the building. The projections would also be viewable from the many nearby restaurants. In such a bustling environment, Gehry says, the projections could work this time.

Between the Colburn buildings and the Grand complex, along with the Museum of Contemporary Art, the Broad, Grand Park and the four buildings of the Music Center, that stretch of Grand Avenue will house more culture and performance spaces in close proximity than almost anywhere in the U.S., on par with Lincoln Center in New York and the arts district in Dallas.

As for Gehry’s coveted orchestra pit, it might not be too far off either.

Gehry says he’s in talks with the Music Center about it. He’s on the board of the L.A. Philharmonic and to keep costs down, he’s offered to do the design work for free.

Sherman said that there’s no concrete timeline in place for making such changes to Disney Hall. But that “any changes could potentially be in sync with the opening of the Grand.” The concert hall, he adds, is “an amazing building, acoustically perfect, and we want to fulfill Frank’s dreams, and the L.A. Phil’s dreams and the L.A. Master Chorale’s dreams.”

Standing on the studio floor of his offices, Gehry’s eyes settle on a tiny, cardboard version of Disney Hall in the distance. The popularity of the building has helped bring in new, more diverse and younger audiences to see concerts, he says.

“I think it’s kept alive classical music and it’s taken it into the 21st century. It’s always filled. Which is something, a lot of them aren’t.”

This pleases the architect immensely. Because in Gehry’s eyes, it all comes down to the music.

“I just love doing concert halls,” he says. “I like the culture of the musicians, all the kinds of people that are involved. I think it’s a magic thing.”

Follow me on Twitter: @debvankin

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.