Critic’s Notebook: LACMA’s concrete wall problem: Why a chic design comes with consequences

- Share via

How do you hang paintings on concrete walls?

“With great difficulty” is the joke answer.

“With great difficulty” is the serious answer too. Hanging paintings on cast concrete isn’t easy.

But that’s apparently what the Los Angeles County Museum of Art has in mind, beginning in four or five years, when a controversial $650-million structure opens on the Wilshire Boulevard campus. Replacing four existing buildings, the new 109,900 square feet of galleries will feature hundreds of permanent collection paintings hanging on concrete. The gallery walls will be made of the stuff.

The County Board of Supervisors voted last month to release $117.5 million toward the nutty idea, urged on at a pitiful public hearing by movie-star cheerleading from Brad Pitt and Diane Keaton, plus a cast of characters all with vested interest in approval. A week or so later, the public got a chance to see a few images of the latest design. (Nice timing.) LACMA opened a small space on the ground floor of the soon-to-be-torn-down Ahmanson Building to show what Swiss architect Peter Zumthor, 76, has been up to lately.

The modest show includes a general site plan, a project timeline, some boosterish textual explanations and a pair of digital slide shows — one for earlier Zumthor projects, built and unbuilt and mostly in Europe, the other for 11 renderings of the new LACMA. All three gallery interiors sport walls of horizontally striated concrete.

Zumthor got the museum job 11 years ago. Plans for what he would build have changed several times since then. Most attention has focused on the exterior — an organic undulation that looks like a 1930s Jean Arp bas-relief sculpture raised on cubic, Brancusi-like pedestals.

The luminous digital drawings of the exterior radiate a relaxed, blissful glow for cars streaming by and people milling about beneath clear blue skies streaked with delicate clouds. Architectural renderings like these are designed to make a sales pitch — LACMA, after all, still needs to raise tens of millions of dollars (and satisfy supervisors) to build it — so the bunkum level runs high.

They’re like those annoying TV ads for erectile dysfunction, the ones where a naked, hand-holding couple stretched out in separate bathtubs gazes out over an endless sea or primeval forest and contemplates the (false) promise of never-ending youth. Tiepolo would be proud.

The interior is more of an unknown. That’s where the art will be, but even at this late date no floor plan or gallery layout is available for public perusal. (A request to see one went unanswered.) There are only those three new renderings — and they’re hilarious.

Thanks to software, paintings from the collection, all European and of sizes large and small, are inserted into the stylishly austere rooms. So is what appears to be one of the collection’s great treasures: a magnificent 9th century BC Assyrian relief of a winged deity escorting King Ashurnasirpal II through his honored earthly passage.

Don’t count on that actually happening (the hanging, not the escorting). In real life, the carved alabaster block weighs just under a ton, but in digital life it can hover beautifully up on the wall.

So, how do you hang paintings on cast concrete?

Suspending pictures on wires secured to a high picture rail, as Victorians sometimes did, doesn’t do the trick. In earthquake country, the last thing you want when a temblor hits is for your suspended Georges de La Tour masterpiece to start slapping against the wall.

Drilling is the answer.

To confirm that assumption, I checked with a number of preparators with extensive experience installing paintings in art museums, commercial galleries and homes. When I explained my question, most groaned. All had essentially the same explanation.

Get an electric tool, bore a hole into the concrete, pound in an anchor (plastic or lead) with a hammer, then screw the hook or other hanging device into the anchor, which should expand to make a tight fit.

And if you want to move the painting?

Unscrew the hooks and pull out the anchors, further damaging the wall and requiring the holes to be filled with fresh concrete. (Be careful if you need to drill a hole in the same place later, as a patch may not be as secure.) With more conventional drywall, a hole is easily spackled and painted over, but concrete in-fill leaves a visible scar.

Now, repeat hundreds of times to accommodate LACMA’s diverse collection — a Joseon dynasty mythological depiction of Daoist immortals Zhongli Quan and Liu Hai; the John Singer Sargent portrait of Mrs. Edward L. Davis and her tow-headed boy, Livingston; the rare signed and dated (“Arellano in 1691”) Mexican painting of the Virgin of Guadalupe; Paul Cézanne’s explosive forest landscape in the South of France; and scores more.

The museum has decided to rotate the encyclopedic collection constantly, abandoning more permanent displays. So, multiply those numbers.

Wall labels identifying the paintings? Few are shown in the renderings, but I suppose Velcro might work. Or, maybe your smartphone GPS can call them up with something like face-recognition technology.

LACMA Director Michael Govan is unperturbed by the idea of paintings hung on concrete. He has said it’s done all the time at Zumthor’s one other art museum built from scratch, the handsome little Kunsthaus Bregenz in a resort city at the Austrian edge of scenic Lake Constance.

Well, not exactly. The 20,000-square-foot Kunsthaus (less than a fifth the size of LACMA’s planned galleries) is a four-story contemporary art space with a tiny collection.

Its lantern-like rooms of concrete and semi-opaque glass most often host shows of sculptures, installations and video art by living artists. This year’s schedule is typical: one exhibition with recent paintings hung in one of the building’s four floors, while three “not-painting” shows round out the bulk of the calendar.

So, yes, it can be done. You can, indeed, hang paintings on concrete walls. Which begs the question: Why would you want to?

You can indeed hang paintings on concrete walls. Which begs the question: Why would you want to?

I’m sure it could look glamorous. (See the stylish digital rendering with the Rembrandt portrait of prosperous Dutch grain merchant Martin Looten.) I’m also sure that, on the day it opens, the place will look as dated as a skinny black Prada suit.

That’s because spare, raw, unadorned concrete is a signature material of Minimalism. Zumthor is a Minimalist architect, and 1960s Minimalist art is Govan’s favorite kind. (Born in 1963, just as the style was getting off the ground, he studied to be an artist before getting detoured into museum administration.) Two generations ago, Minimalism represented a powerful break with conventional structures of painting and sculpture.

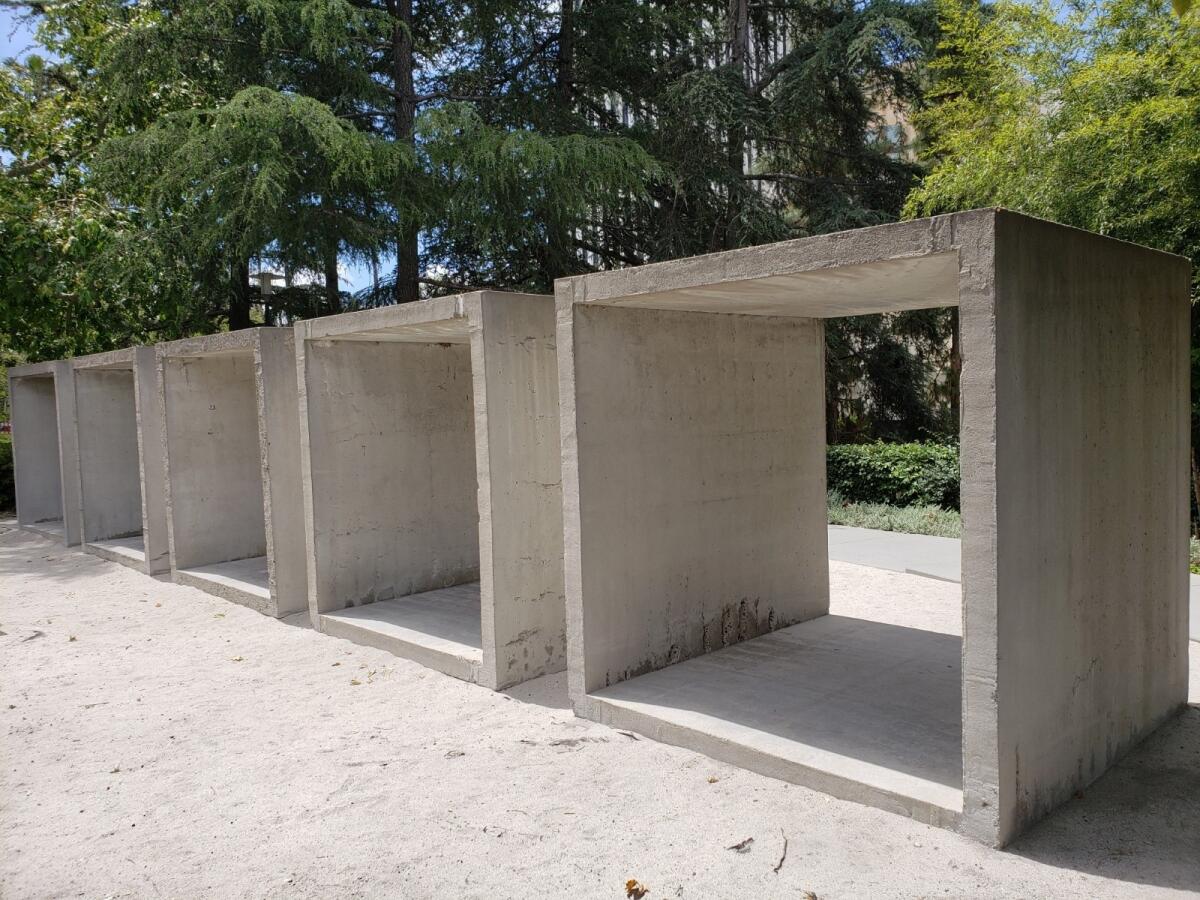

Take Donald Judd’s 1977 “Untitled (for Leo Castelli),” a reinforced-concrete sculpture composed of five empty boxes, each 7 feet square. Nothing separates the industrial forms’ insides from their outsides, erasing traditional claims that art is an outer exposure of an artist’s submerged inner life. Utterly impersonal, the anonymous modular geometry creates a sleek object emphasizing contemplation. A viewer observes himself observing.

Minimalism was a classic anti-art strategy, annulling every established trace of modern abstract art by slamming on the brakes and reversing gears. The Judd is a prime example.

REDESIGN: The future LACMA experiences shrinkage — and shapeshifts yet again »

Or, it was a prime example. Badly damaged now, the sculpture has been quietly crumbling away in LACMA’s east garden for years, edges chipped, surfaces scaly and rusty rebar exposed like the ribs of a decaying carcass.

(If you find a dead body in the street, decency demands covering it with a shroud. The same goes for a dead sculpture in an art museum’s garden. LACMA should be embarrassed.)

Concrete gallery walls are likewise an iconoclastic token. Common drywall is the usual museum choice.

The stone and block walls of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Cloisters are an exception to the rule. But, notably, that Medieval collection’s installation — mostly sculptures, liturgical objects and tapestries — rarely changes, while its supreme masterpiece painting, the Merode Altarpiece, stands on a shelf.

Chucking practical drywall signals a loathing for conventional cultural piety. The material gesture further proclaims the preeminence of structural fact. It avows an anti-elitist attentiveness to the industrially humdrum.

At least, it did way-back-when. For a thrilling example from 1922, see the tilt-up concrete walls of West Hollywood’s landmark Schindler House.

Anti-art aesthetics were first brandished as a sharp, unsettling disruption of the smoothly running status quo even earlier — by Dada artist Marcel Duchamp a century ago. New appreciation for Dada and for industrial architecture were both instrumental in Minimalism’s emergence.

Now that the strategy is universally accepted, however, it no longer has the power to muck up the rules. It is the rule. Anti-art aesthetics are the status quo. LACMA’s Minimalist design isn’t bold or progressive; it’s echt establishment. The gesture is antiquated — a pricey emblem of institutional taste.

For a glamorous example, see Austria’s Kunsthaus Bregenz.

LACMA’s plan for elevated horizontal architecture claims to erase a pecking order that puts one culture higher than another on a vertical ladder of artistic expression. But hostile concrete gallery walls are just old-timey Euro-American anti-art inflated to institutional scale. Minimalism colonizes diverse global cultures as surely as the Greco-Roman temple designs of yesterday’s art museums did — only in a newer, shinier, more modern way.

What, you expected something revolutionary from a hugely pricey building funded by local billionaires and sanctioned by county government?

Concrete is also beige-gray. So forget color ever again gracing LACMA’s gallery walls. Color can set a mood, tag an era, help establish a theme, introduce variation or visually resonate with the art. Applied color is irrational and playful, while solemn gray — intrinsic to the material — is “honest.” Heaven forbid looking at art should involve illuminating delight, never mind engaging with curatorial artfulness.

Faith in concrete’s sober virtue reminds me of all the cooing back in 2008-2010 over “column-free space” in Renzo Piano’s LACMA designs for BCAM and the Resnick Pavilion. Wide-open, uninterrupted interiors without pesky ceiling supports were touted as representing curatorial freedom and artistic respect — the liberty to subdivide interior museum space in whatever way might best flow from the art being shown.

Yes, but: Art installation budgets roughly tripled when BCAM and Resnick opened, several people with direct knowledge of the column-free plan told me. Earthquake-zone building codes guide construction of those temporary interior walls. The structural demands approximate those for permanent walls — including their expense.

Freedom has its costs. If the Resnick gallery layout for last year’s (dreadful) exhibition, “To Rome and Back: Individualism and Authority in Art, 1500-1800” looked familiar, that’s because you saw it the year before in (the great) “Painted in Mexico, 1700-1790: Pinxit Mexici.”

And before that for “Los Angeles to New York: Dwan Gallery, 1959 –1971.” Seven hundred years of international contemporary art, Latin American Baroque paintings and European Renaissance sculptures, paintings, graphics and decorative arts were all shown in the same container. So much for tailoring galleries to the unique demands of what’s on view. Too costly.

The concrete-walled spaces in between the concrete-walled rooms have been branded as “meander galleries” — ad-speak for what mere mortals know as hallways. The renderings overflow with twenty- and thirty-something visitors browsing about, the selfie crowd coveted by marketing departments everywhere, their designer hand bags, quaint man-buns and athleisurewear on casual parade.

Not a chair or bench is anywhere to be seen in the pictured indoor acreage, which will be nearly the size of two football fields. Museum fatigue — a phenomenon from being on your feet for hours, first analyzed in a scientific journal back in 1916 — disappears into the digital glow.

Zumthor’s imposing building is a bridge with a glass-walled perimeter straddling Wilshire Boulevard, the city’s automotive spine. The show’s wall text piously bills this design as taking a moral stand that chooses cultural transparency over opacity.

In reality, the new LACMA just makes an Instagrammable spectacle of the conspicuous consumption inside. Art museums have been public showcases for the aesthetic preferences of the affluent ever since the 18th century, when Rome’s papal Capitoline Museum and Paris’ palatial Louvre Museum were founded. That’s not a knock, just an inescapable fact. Like church and state then, plutocracy now is not transparent — so let’s not pretend otherwise.

Similarly, let’s not pretend that concrete gallery walls are a magnificent idea. Should they be built, let’s also hope they hold up better than that hapless Minimalist sculpture languishing out in LACMA’s soon to be torn-up garden.

A CRITIC’S LAMENT: LACMA, the Incredible Shrinking Museum »

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.