Review: In the face of fascism, he showed industrial-strength optimism: The art of Moholy-Nagy at LACMA

- Share via

The optimism of László Moholy-Nagy is staggering.

Here was an artist who, born into difficult circumstances in a small farming village in southern Hungary, turned 19 just eight days before Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated at Sarajevo in 1914, igniting the fuse of the Great War. Moholy-Nagy barely survived military duty on the unspeakably brutal Russian and Italian fronts.

Then he arrived in postwar Berlin just as the Weimar Republic ushered in waves of chaotic upheaval, ending with the 1933 rise to power of gruesome National Socialism. His expensive dream of merging art and industrial technology in large-scale dramatic spectacles ran headlong into the 1929 economic collapse, soon enough followed by the arrival of Albert Speer, Adolf Hitler's architect, and his extravagant Nuremberg mass rallies. The Jewish artist migrated through Amsterdam and then London to Chicago, where he died of leukemia at 51 — a short year after the cataclysm of World War II came to a crashing end.

Despite the tumult, you might never know any of this from looking at his art.

On the evidence of “Moholy-Nagy: Future Present,” a large and fascinatingly beautiful show that opened recently at the

Curiosity, color, wry humor, excited trial and error, prolific innovation — the artist grabbed an avant-garde sensibility and never let it go. “Future Present” asserts that this world is the best possible world, and inevitable change should be courted, its possibilities maximized. Moholy-Nagy is often called a utopian, but optimist seems a better fit.

The first painting is a zigzagging array of red and black stripes and triangles, all pierced by thick bars that are like I-beams merged with golden shafts of light. The 1919-20 abstraction of radio towers and railroad switches is of modest size, executed on rough-hewn burlap. Postwar shortages may have had something to do with the burlap choice, but it’s also working-class canvas for a painter engaged in constructing pictures.

The painting’s imagery of Industrial Age mechanisms of communication and transport resonates all the way to the last room, 300 works later, where three sculptures are suspended on wire from the ceiling. Twisted planes of transparent plexiglass pierced by tangled metal rods refract and reflect light. Linear drawings in space, they cast moving shadows on adjacent walls to become four-dimensional animations.

In between are paintings and sculptures, films, works on paper, graphic designs, stage sets and a reconstruction of an adventurous 1930 exhibition design mixing glass-and-metal walls, film projection and kinetic sculpture, as well as several types of photography. Moholy-Nagy was prolific, his interests sweeping.

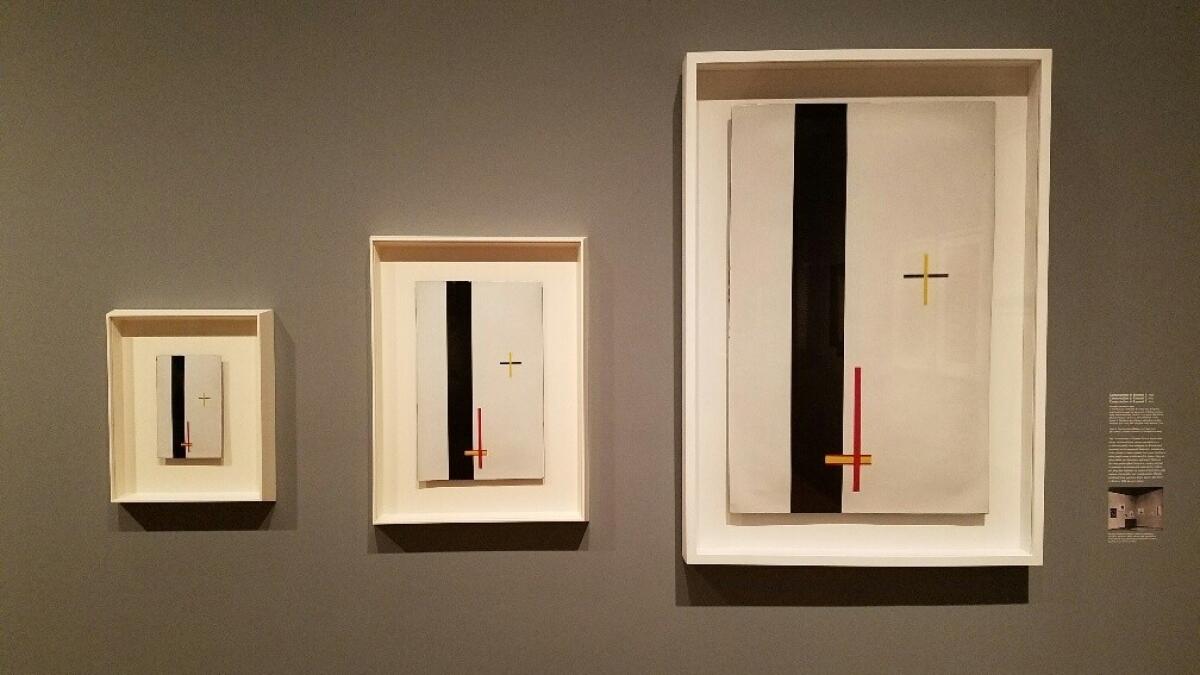

Who else would come up with the so-called “telephone paintings” that he made — or, more precisely, had made for him — in 1923? The artist is said to have called up a local German sign maker and conveyed mathematically precise design instructions and color choices for Constructivist images in enamel on copper.

Identical compositions come in small, medium and large sizes, depending on one’s needs or desires. Russian avant-gardists had been applying abstract designs to teacups and clothing, but Moholy-Nagy was thoroughly testing the possibilities of industrially manufactured paintings.

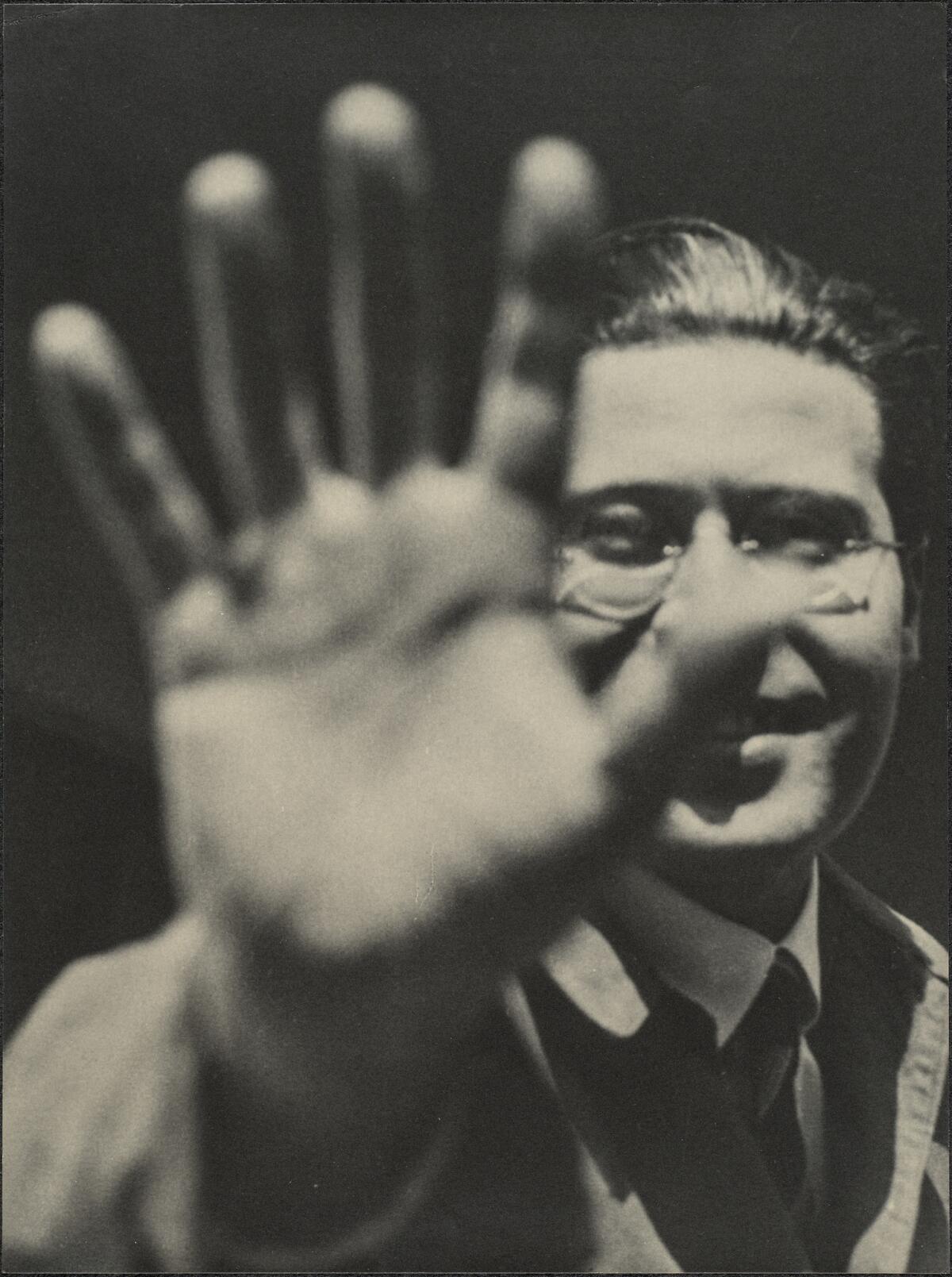

In the five years (1923 to 1928) that he taught at the Bauhaus, the avant-garde design school founded by architect Walter Gropius, Moholy-Nagy was instrumental in shifting the curriculum away from handcraft toward industrial fabrication. “To be a user of machines is to be of the spirit of this century,” the artist wrote (optimistically). In “Photograph (Self-Portrait With Hand),” the hand of the artist held close to the camera’s lens blurs out of focus, caught between his grinning, bespectacled, crisply delineated face and the inherent nature of the image machine.

Moholy-Nagy was born in 1895 and raised by a single mother; his father disappeared. He left rural Hungary at 18 to study law at the University of Budapest but was conscripted to serve in the Austro-Hungarian artillery during World War I. In the trenches he began to draw. Wounded and sent to hospital, he abandoned law for art.

His postwar rise was rapid. With successful shows at Berlin’s avant-garde outpost, Galerie Der Sturm — the Storm — he was selected at just 28 to teach the foundations course on the Bauhaus faculty.

The women in his life were important to his artistic development. His first wife, Lucia Schulz, whom he met in Berlin in 1920 and separated from in 1929, was a talented photographer. His second wife, writer Sibyl Pietzsch, whom he met at a film studio and married in 1932, assisted in the writing and commercial design work that he produced after leaving the Bauhaus. Fleeing the Nazis, the couple finally landed in Chicago, where

This is the largest, most complete retrospective of the artist’s work since the late 1960s. (A thumbnail-sketch of aspects of his career, “The Paintings of Moholy-Nagy: The Shape of Things to Come,” was at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art in 2015.) The show was jointly organized by New York’s Guggenheim Museum, the Art Institute of Chicago and LACMA, and their respective curators, Karole P. B. Vail, Matthew S. Witkovsky and Carol S. Eliel.

It’s a revealing trio. The Guggenheim, founded as a museum of non-objective art, was a primary collector and supporter of Moholy-Nagy’s work. Chicago was his American home, and LACMA is a premier venue for shows of Modernist German art.

Given an artist who taught at design schools founded by architects, the exhibition’s installation was appropriately designed by an architecture firm, Johnston Marklee. Not only does it look smashing, with rich gray walls lined in black borders that somehow echo an era before Kodachrome and the proliferation of color photographs, but the scheme also elucidates the art.

A sequence of wide, narrow galleries open at both ends allows a visitor to follow the generally chronological installation along continuous walls. It begins with geometric abstraction, which is so common today that it can be difficult to imagine just how radically eye-popping it was a century ago. In the manner of Dada nonsense art, but without Dada’s penchant for social disgust, Moholy-Nagy’s Constructivist explorations incorporate numbers and letters as abstract shapes and “visual sounds.”

These are followed by photographs. Light, the essential agent of photography, then becomes a lifelong theme. In the wake of Moholy-Nagy’s Bauhaus years, paintings employ transparent panes of color while free-standing hybrids are painted on undulating plexiglass.

The paintings are not always resolved, but the photographic work shines. Some are camera-less, in the case of photograms made by placing objects on photosensitive paper and exposing it to light, while others are photo montages mixing photographs and drawing.

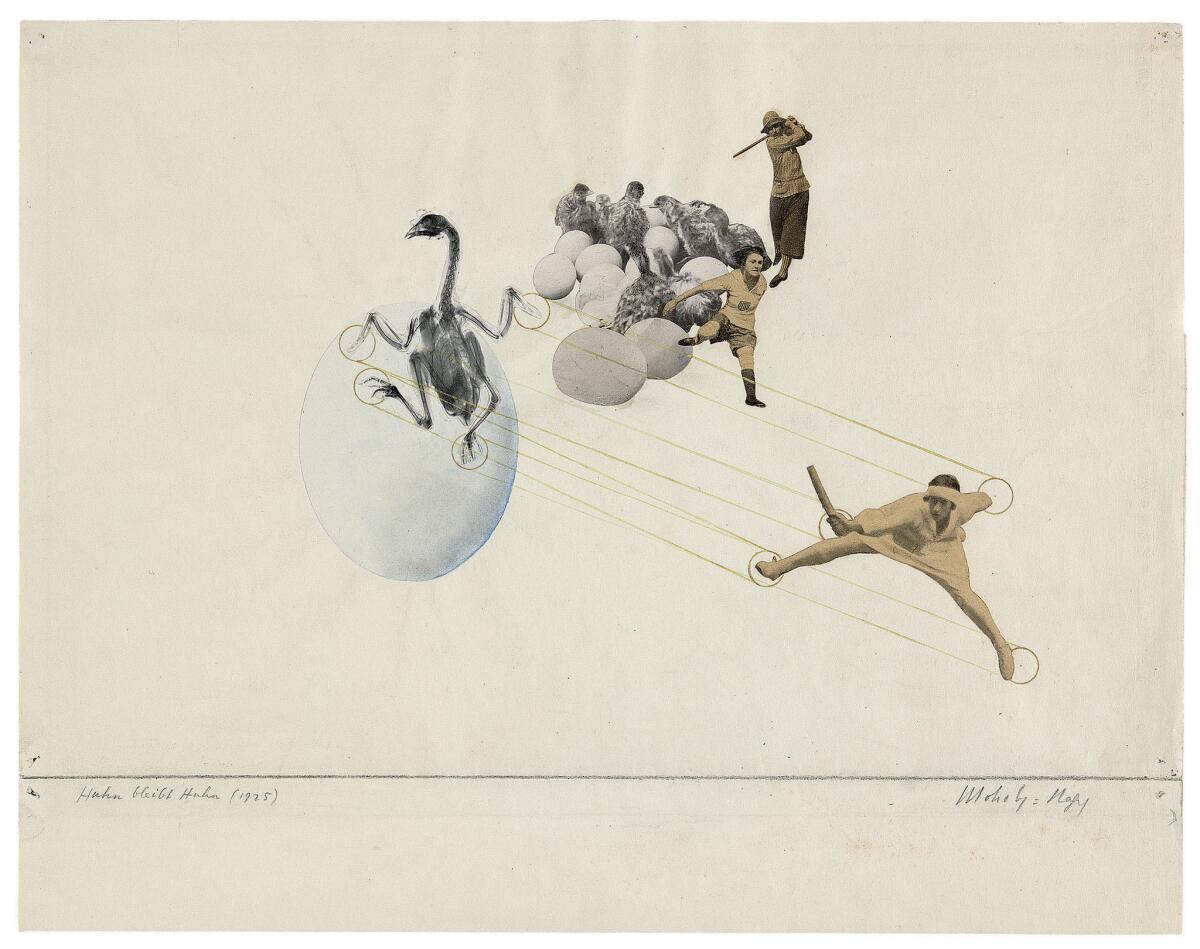

Several turn on sly wit, as in a lively 1925 photo montage that pairs female athletes with chicks emerging from eggs. Weimar women had won the vote in 1919, and the swift emergence of what was dubbed the New Woman gets warmly embraced in a playful image where a newly active public life harmoniously coexists with a more traditionally maternal symbol. Newborns abound.

The installation’s most dramatic feature is a corridor of doorways that slices on the diagonal across the entire exhibition, like a fantastic Surrealist hall of infinite expansion. The doorway openings are cut on an angle and seem to get progressively narrower, as if a one-point perspective drawing had popped into three dimensions. Slip through them and interrupt the otherwise orderly flow through the artist’s career.

In fact, as a palpable aid to understanding the spatial expansion and organic discombobulation that undergirds so many Moholy-Nagy compositions, I recommend walking the length of the doorway corridor, front to back, at least once. At one remarkable point, a doorway opening even casts a pattern of angled shadows and light rays across the floor, visually rhyming with “A 19,” a 1927 painting of intersecting color planes hanging on the wall beside it.

The source of Moholy-Nagy’s optimism is, of course, lodged in the mystery of human personality. Yet, at least in part, it also seems to embody a considered, committed faith. It’s as if the abundant horrors of the modern world, which he encountered starting at a tender age, could be navigated only through a deep devotion to the power of modern technology, education and — not least of all — art.

In these trying times, that’s a lesson worth experiencing.

‘Moholy-Nagy: Future Present’

Where: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 5905 Wilshire Blvd., L.A.

When: Through June 18; closed Wednesdays

Information: (323) 857-6000, www.lacma.org

Twitter: @KnightLAT

ALSO

Diego Rivera's Cubist masterpiece arrives at LACMA

Jimmie Durham's art throws some well-aimed stones

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.