With Lucas Museum on the way, Natural History Museum plans another makeover

- Share via

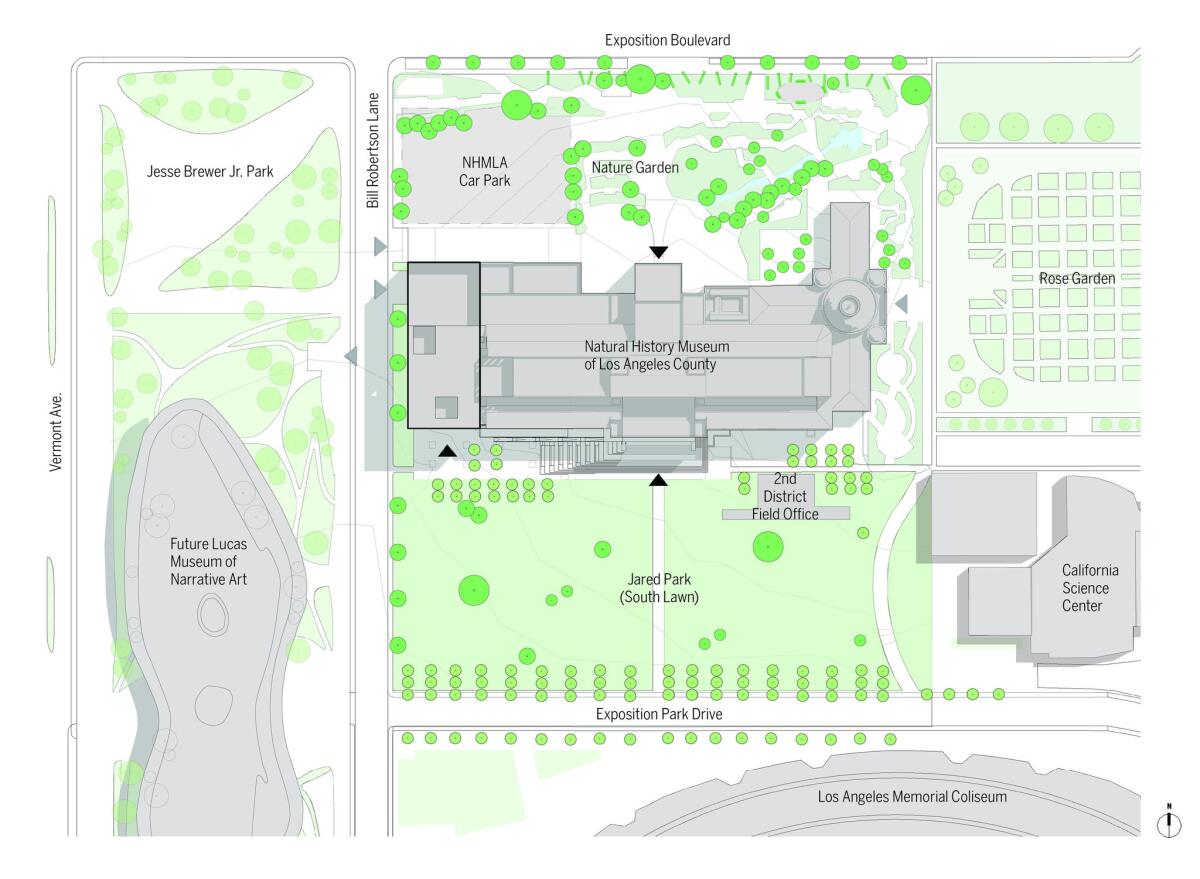

Exposition Park is getting crowded. And that’s both a challenge and an opportunity for the Natural History Museum, at 104 years old the park’s oldest cultural tenant.

On Wednesday the museum will announce its latest proposal for a significant makeover, this one by Los Angeles firm Frederick Fisher and Partners Architects. NHM Director Lori Bettison-Varga, who joined the museum in 2015 after six years as president of Scripps College, describes it as the first step in a 10-year plan to redesign both its Exposition Park home and its second location, the Page Museum and La Brea Tar Pits.

The NHM announcement is being made separately from an ongoing master-planning effort for Exposition Park, which is owned by the state and overseen by the Office of Exposition Park Management. The park’s master plan was last updated in 1993.

By sharing its proposal with The Times early this week, the museum, a county institution, is getting out in front of a press event planned Friday by OEPM. Called “Exposition Park: Past, Present, Future,” it will include information about the forthcoming

“We have to move ahead,” Bettison-Varga told me as we were walking along the exterior of the museum on a recent afternoon.

Fisher’s proposal, still in the conceptual-design phase, focuses on the southern and western edges of the museum building, which not coincidentally are the sides closest to the Lucas Museum site. The NHM also hopes to show a more welcoming face to potential visitors who arrive from the nearby Expo Line station and walk south into the park on Bill Robertson Lane, along the museum’s western edge.

The plan calls for replacing the 1960 Jean Delacour Auditorium on that end of the building, which is now used as a kind of makeshift storage room, with a three-story addition. Including its basement level it would add about 60,000 square feet of space, bringing the museum’s total square footage to 485,000, without dramatically expanding its footprint in the park.

The addition would take the form of a glass cube holding a new entrance and a flexible, multipurpose event space at ground level. If you’re thinking that the museum already has a glass-cube entry hall, you’re right: the firm CO Architects added the Otis Booth Pavilion to the north side of the museum, facing Exposition Boulevard and the USC campus, in 2013.

Fisher, whose firm designed recent additions to the Huntington Library and Descanso Gardens, promises that his glass box will have a more delicate personality from the earlier one. The facade will include large vitrines to hold key objects from the NHM collection, suggesting an oversized, transparent wunderkammer, or cabinet of curiosities. (Bettison-Varga called it a “curated facade.”) The addition would include a double-height entry hall, with views toward the park, as well as a rooftop restaurant.

On the southern side of the museum, facing the Coliseum, Fisher’s proposal calls for smoothing out the entry stairs so that they seem to melt into the lawn (officially Jared Park) that runs between NHM and the stadium. The plan also calls for stretching a horizontal band of glass along the lower part of the façade, bringing light into a corridor connecting the new corner entry and the existing entry hall on that side of the building. The idea is to recast the entire southern facade as a new front porch.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

The Natural History Museum opened as the Los Angeles County Museum of History, Science and Art in November 1913 (just as the city was celebrating the completion of the Owens River Aqueduct). The original building, still anchoring the NHM’s eastern end, is a blend of Spanish Revival, Romanesque and Beaux Arts details unique to L.A. architecture, with an elaborate terracotta façade overlooking the rose garden of what was then called Agricultural Park.

Over the years the museum has grown in a fashion both ambitious and piecemeal, adding or remaking space in 1924, 1927, 1960, 1974 and 1976 and more recently in 2010 (a retrofit of the 1913 building), 2011 (Dinosaur Hall), 2013 (the Booth Pavilion, the Becoming Los Angeles exhibition and gardens by Mia Lehrer and Associates) and 2016 (new Butterfly Pavilion). The result of those recent changes is a museum that reaches out more effectively to the public but remains something of an architecture jumble, particularly on the edges where Fisher has so far concentrated his work.

Bettison-Varga’s plans for the museum are inextricably linked with projects remaking the rest of Exposition Park and surrounding neighborhood. Along with the Lucas Museum, the soccer stadium and the Expo Line, these include a renovation of the Coliseum set to be completed in 2019 and a permanent building at the California Science Center for the space shuttle Endeavour.

These new facilities will bring new waves of visitors to Exposition Park (as will the 2028 Summer Olympics, for which both the Coliseum and the soccer stadium will serve as key venues). They will also increase the sense of competition among the park’s various tenants, each one vying for a bigger (or least sizable) piece of a bigger attendance pie. The park now attracts about 4 million visitors per year.

It would be overstating the case to say that there’s an architectural arms race underway as a result. Fisher’s design remains little more than a sketch at this point but is, like most of his work, the opposite of bombastic, with a communitarian streak as strong as its modernist one.

THE NEWS STORY: George Lucas picks L.A. for his museum »

THE ANALYSIS: What does the Lucas Museum say about L.A. »

Yet the arrival of the Lucas Museum, a sleek, white battleship of a building by Chinese architect Ma Yansong, certainly has every institution in the park rethinking its strategic plans and diving into its Rolodex. The length of the planned Lucas building has tended to obscure, in renderings, just how tall it will be; at 100 feet the museum will be higher than the NHM and more than hold its own against the giant curving form of the Coliseum.

No wonder the NHM sees a need to remake that corner of its building. There are programmatic ideas driving the plan as well. The museum wants to better advertise the strength of its collection, which at 35 million specimens is second only to the Smithsonian in size. The most recent redesigns have left roughly 40% of the museum’s public spaces untouched.

The plan is also emblematic of significant shifts in Los Angeles urbanism. Beginning in the 1920s and for many decades after, major L.A. cultural institutions and stadiums seemed to enjoy nearly endless elbow room, occupying their very own hilltops (Griffith Observatory, Dodger Stadium, Getty Center), arroyos (Rose Bowl) or seas of asphalt laid down for parking (the Forum in Inglewood and, again, Dodger Stadium).

Exposition Park had always existed as a counterweight to this kind of dispersal, suggesting with its closely packed collection of venues a centripetal urbanism instead of centrifugal one. But it was increasingly an outlier as the 20th century wore on, a remnant of an earlier kind of city-making that made less sense for self-consciously modern and car-obsessed Southern California.

Now that Los Angeles has run out of hilltops to build on and lost its interest in plugging up arroyos, the model suggested by Exposition Park, with a wide variety of civic institutions reached easily by transit, is increasingly relevant and attractive, despite the ad hoc way it has grown in recent decades. The decision to put both the soccer stadium and the Lucas Museum in the park can be read cynically (this has always been an easy and attractive place for civic leaders to locate a giant new building) or more optimistically (this is a proving ground for the emerging Los Angeles, a city rejecting the hilltop-museum model and learning to live closer together).

I’d say some combination of the two is appropriate. Planning for the park has been scattershot in recent years, with additions like the Lucas Museum seeming to trump rather than follow the master plan. At the same time the shifting landscape of Exposition Park could help point Los Angeles civic architecture in a new direction, requiring institutions to think of their buildings as landmarks in the round, open and engaged with the public on all sides rather than just the one nearest the parking lot.

Twitter: @HawthorneLAT

ALSO

Review: Bellini masterpieces at the Getty make for one of the year's best museum shows

Two decades after Gehry's Guggenheim Bilbao, where does architecture stand?

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.