Irving Penn dies at 92; a giant of photography

- Share via

Irving Penn, a grand master of American fashion photography whose “less is more” aesthetic, combined with a startling sensuality, defined a visual style that he applied to such varied subjects as designer dresses, cigarette butts and cosmetics jars, many of them now- famous photographs owned by leading art museums, has died. He was 92.

Penn died Wednesday at his apartment in New York City, said his brother, film director Arthur Penn. The cause was not given.

In 1943, Penn started contributing to Vogue magazine and became one of the first commercial photographers to cross the chasm that separated commercial and art photography.

He did so in part by using the same technique no matter what he photographed -- isolating his subject, allowing for scarcely a prop and building a work of graphic perfection through his printing process.

Critics considered the results to be icons, not just images, each one greater than the person or object in the frame.

“His approach was never obvious,” Phyllis Posnick, who collaborated with Penn at Vogue, told The Times on Wednesday. “He would make us go further and dig deeper and look beyond the obvious solution to a photograph to find something that was unique. He had a great wit, and you see some of that in his pictures.”

Penn was a purist who mistrusted perfect beauty, which brought an engaging tension to his fashion photographs as well as his still lifes and portraits. One of his best-known shots for Vogue in the 1950s shows an impeccably dressed model glancing sideways through a veil that covers her face, as if she wasn’t ready for her close-up. Lavish textures, the rich shadow and light became Penn’s trademark.

Cosmetics ads

His most familiar photographs are the cosmetics ads he shot for Clinique that have appeared in magazines since 1968. Each image is a balancing act of face-cream jars, astringent bottles and bars of soap that threatens to collapse. He photographed them at close range to suggest the monumental scale of Pop art soup cans.

A notorious perfectionist, he traveled widely, carrying his own studio to the ends of the earth to photograph Peruvians in native dress, veiled Moroccan women or the Mudmen of New Guinea. Many of his personal photographs are collected in his books, luxurious objects in their own right.

Despite an obvious appreciation for the art and craft of a beautifully made dress, Penn strained against the unreachable world it represents. To escape it, or perhaps contest it, in the late 1960s he started photographing crushed cigarette butts and street debris.

He shot butts the way he often photographed designer dresses -- close up, with a graphic precision, against a white background. He then built his negatives into “platinum-palladium” prints, a meticulous and costly process that involves repeated printings of a negative on one piece of paper to create an extraordinary depth and richness.

New York’s Museum of Modern Art found the cigarette butts exhibit-worthy in 1975. Many reviewers, who questioned whether anything by a fashion photographer belonged in an art museum, called the work pretentious. A similar debate stewed during a 1977 exhibit at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art of Penn’s photos of urban debris.

Far-sighted reviewers praised Penn’s ability to turn discarded objects into art, but the contradictions in his work still bothered some.

“Penn’s models may be alluring, but he emphasizes their self-absorbed beauty in a way that makes them seem cold and inhuman,” the Atlantic magazine wrote in 1985, reviewing a retrospective of his work at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1984.

Painstaking treatment

Penn continued to photograph what he wanted -- Hells Angels in leather and chrome, European craftsmen in full uniform, African chiefs with feathers, famous artists and writers. Each subject received the same painstaking treatment.

“He didn’t worry about questions of art versus commerce,” said Colin Westerbeck, a former photography curator at the Art Institute of Chicago, which owns a large collection of Penn’s work. “Photography is a mass medium available to anyone. A few geniuses, like Irving Penn, redeem it,” Westerbeck told The Times in 2003.

Penn’s contrary streak found expression early in his career. Starting in 1948, after shooting designer dresses for Vogue by day, Penn made 70 photographs of fleshy, curvy nudes as a personal project. After finishing the series in 1950, he married razor-thin fashion model Lisa Fonssagrives, who appeared in many of his magazine photographs through the ‘50s. The voluptuous nudes were a bachelor photographer’s last fling, Penn later said.

After his wife died in 1992, he made a small series of self-portraits that showed a close-up of his face, fractured and disintegrated as a Cubist painting. They “expressed how he felt at the time,” said photography historian Diana Edkins, a former curator of photography for Conde Nast Publications, including Vogue. “The Penns’ romance lasted their whole life together.”

Penn first exhibited his series of Rubenesque nudes in 1980 as “Earthly Bodies” at the Marlborough Gallery in New York. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City featured them again in 2002.

“What Penn does with an honesty that few of his peers can muster, is remind us that a body, rounded and grounded, is one of the more enthralling objects on earth,” Anthony Lane wrote in the New Yorker magazine in 2002.

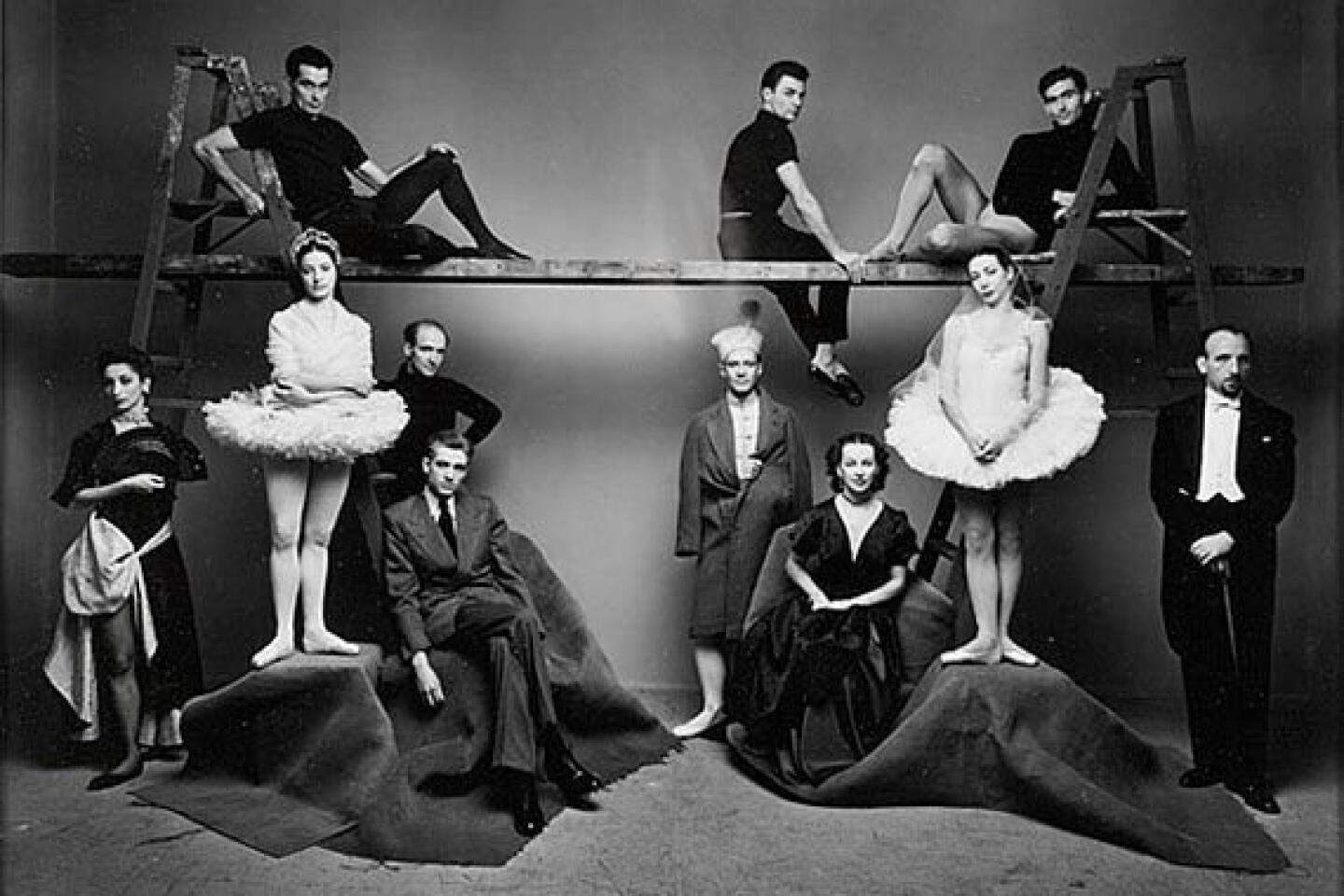

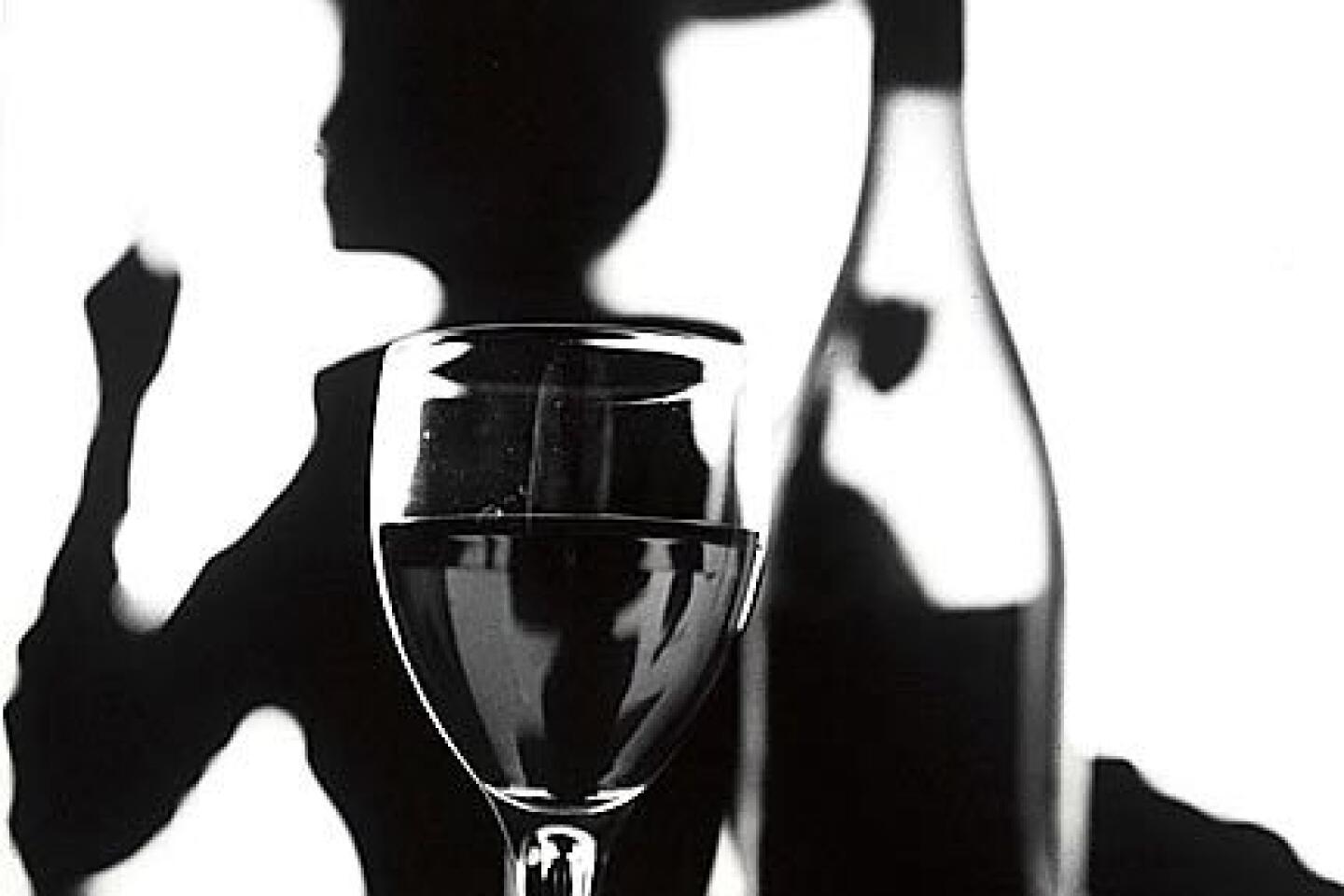

In his early work, through the 1950s, Penn used a few props. A martini glass, a teapot or a bar stool, each one an elegant classic. Later he eliminated props and set his models against white or stormy gray backgrounds. What brought life to those portraits came from the people he photographed. Subtly, he captured human evanescence.

Penn developed his style during the same years that his near contemporary, Richard Avedon, was getting established at Harper’s Bazaar magazine. Avedon made the streets his studio and loved movement and expression. Penn brought “poetry to immobility,” as one admiring critic, Rosamond Bernier, said of his style.

After Avedon joined Penn at Vogue in the early 1960s, Penn “began to understand that what they wanted . . . was simply a nice, sweet, clean-looking image of a lovely young woman,” Penn said of Vogue in 1991 in the New York Times. “I began to do that, and that’s when I became valuable to them and had 200 to 300 pages a year.

“Up to that point I had been trying to make a picture. Then I began to try to make a commodity. That’s what I’ve been doing in fashion photography ever since.”

Those who worked with Penn said it wasn’t as simple as that. “There is the famous story of Irving photographing a lemon,” Babs Simpson, a former Vogue fashion editor, said in 1990 in Vanity Fair.

“First, you had to buy 500 lemons for him to pick the perfect one. Then he had to take 500 shots of that lemon until he got the perfect one.”

The results were what counted, Penn’s longtime boss at Vogue, Alexander Lieberman, told Vanity Fair. “A Penn photograph,” he said, “will always be a great photograph.”

Minimalist tastes

An elegant man of average height with a soft voice, Penn was known as warm and outgoing. His minimalist tastes extended to his personal dress. For years he wore blue jeans, khaki work shirts and sneakers to fashion shoots as well as art openings.

“His uniform was his way of saying, ‘I may be king of fashion photography but I’m not going to play that game, ‘ “ Edkins said.

His inner world spun on new ideas. Penn experimented with vintage and high-tech cameras, unusual lenses and antique printing techniques. He designed some of his own equipment to gain greater control over light on his subjects.

Penn said the constant change of subjects fed his imagination. He once recalled a perfect week in 1950 in which he went from photographing Italian sculptor Alberto Giacometti to photographing French butchers to a session with models wearing French couture fashion, all in the same studio.

His series of more than 250 photos of butchers, bakers and others in “The Small Trades,” was acquired last year by the J. Paul Getty Museum and are on view now through Jan. 10.

“To me it was like a balanced meal,” Penn recalled in 1991 in the New York Times. “The butchers in between invigorated the fashions.”

Although art critics struggled to place him, Penn’s advertising clients declared him an unqualified genius.

“He never ceases to amaze me,” Jane Mauksch, a creative director for Clinique, said in a 2002 interview with the Singapore Straits Times. “I feel a little like the fan who’s talking to Picasso.”

Besides Clinique, Penn also photographed ads for Chanel and for Japanese fashion designer Issey Miyake for some years.

Pricey photographs

Although it took three decades, most of his work was eventually appreciated as art.

“Penn blurred the line between art and commercial photography,” said Stephen White, a photography dealer who held the first Los Angeles exhibit of Penn’s work in 1978. In that show the highest priced photographs sold for $1,500. Twenty years later they would go for 100 times as much.

The son of a watchmaker and a nurse, Penn was born June 16, 1917, in Plainfield, N.J., and grew up in Philadelphia. His younger brother, Arthur, became a successful movie director with “Bonnie and Clyde” in 1967.

Irving dreamed of being a painter and graduated from the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art in 1938.

He moved to New York City and became art director for Saks Fifth Avenue, but quit after four years to travel in Mexico. He spent a year working on his painting, but decided he wasn’t very good at it.

In 1943, Lieberman hired Penn to design cover shots for Vogue that staff photographers carried out. Penn was never satisfied with the results, and Lieberman finally told him to take his own pictures.

“At the time, I didn’t know a Balenciaga from a baseball player,” Penn said in a 2007 interview with Vogue.

His first attempt at fashion photography was a still life with scarf, gloves, leather bag, lemons, oranges and a topaz. The first still life to grace the magazine’s cover, it appeared in October 1943. Penn would go on to shoot more than 150 covers for Vogue.

“His very presence in the magazine each month is both humbling and ennobling for his younger colleagues,” Anna Wintour, the magazine’s editor, wrote in the July 2007 issue that honored Penn at 90.

Penn left New York to serve with the American Field Service as a photographer during World War II and traveled in India as part of his job. A life of travel ensued. One of the most beautiful of Penn’s dozen or so books, “Worlds in a Small Room” (1974), features portraits of tribesmen of Africa and New Guinea.

His ambivalence toward fashion’s illusions never left him. He gave fashion photography the stature of fine art yet constantly made light of it.

At 87, he completed “A Notebook at Random,” a 2004 book that includes test prints and photos with crop lines of well-known images. His aim, he wrote in the introduction, was “to capture a portrait of history in the most insignificant representations of reality, its scraps, as it were.”

His final photograph for Vogue, a still-life of aging bananas, appeared in August.

Besides his brother, Penn is survived by a son, Tom; and a stepdaughter, Mia Fonssagrives-Solow.

Rourke is a former Times staff writer.

Times staff writer Valerie J. Nelson contributed to this report.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.