How Robert Mapplethorpe went from America’s pariah to America’s sweetheart

- Share via

Later this month, when the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art open “Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium,” their joint extravaganza of an exhibition, an extraordinary transformation will finally be complete. The artist will have officially become America’s Sweetheart.

What a difference a generation makes. Not so long ago, Mapplethorpe was America’s Pariah.

In 1989 he was being widely, furiously condemned for including homoerotic photographs and explicit pictures of men engaged in sadomasochistic sex amid his studio-based output — mainly portraiture and floral still lifes. Mapplethorpe had died in March, a casualty of the AIDS epidemic.

SIGN UP for the free Gold Standard newsletter >>

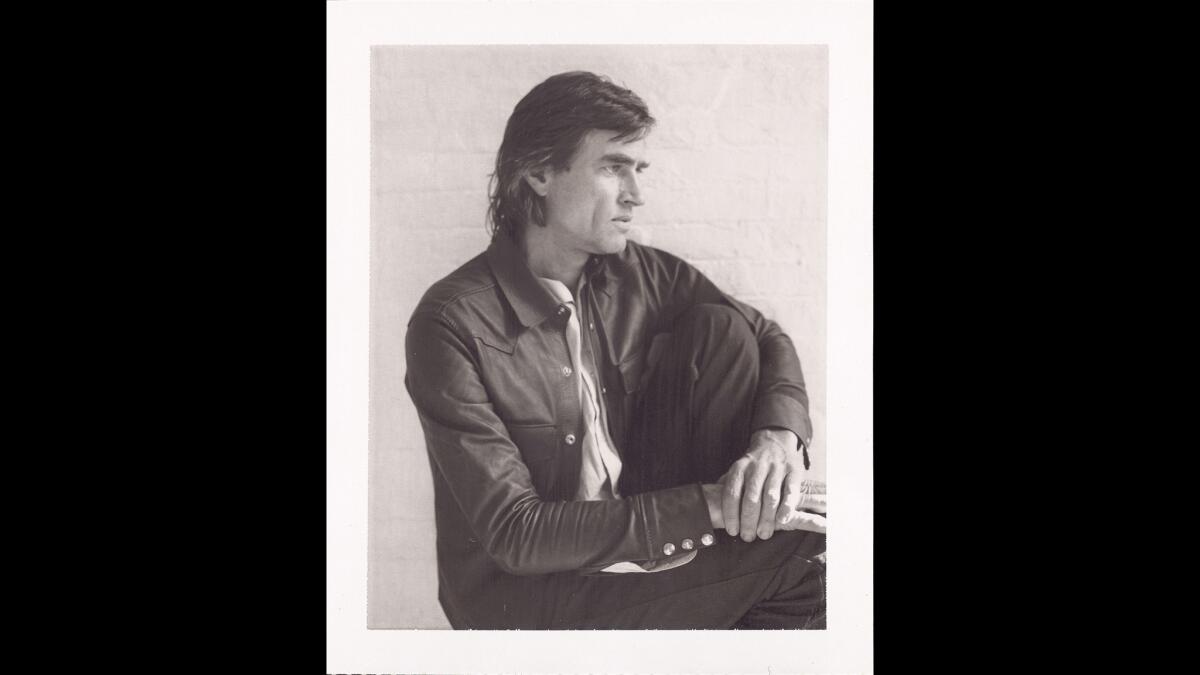

“Sam Wagstaff,” circa 1972.

Fierce art world champions had gone to bat, organizing a retrospective at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art and a traveling show, “Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Moment,” at Philadelphia’s Institute of Contemporary Art. But as those exhibitions opened, his sexually explicit work was dragged through the public mud as a politically powerful instrument in a fractious culture war.

Conservative politicians and pundits excoriated him. Like musty Jack Webb fingering a conspirator, North Carolina Sen. Jesse Helms denounced Mapplethorpe on the Senate floor as “a known homosexual.”

A modest grant from the National Endowment for the Arts that supported a fraction of the Philadelphia exhibition’s costs became an excuse to gut the federal agency. The show’s last-minute cancellation for display at the Corcoran Gallery of Art was the first domino in a cascade leading to that museum’s closure last year, ending a century-long run in the nation’s capital.

Prosecutors charged the participating Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati and its director with promoting obscenity — the nation’s first art museum criminal trial arising from an exhibition’s contents. A jury ultimately acquitted them, but the damage was done. In a 1990 cover story for the national gay newsmagazine the Advocate, I wrote that Mapplethorpe had been made into the Willie Horton of the midterm election season.

Now, a quarter-century on, two prestigious museums have teamed for a large, extravagant exhibition to explore the genesis and maturity of his 1970s and 1980s photographs. The Getty and LACMA are pulling out all the stops for what is shaping up to be the most thorough examination made of his much-discussed career.

Five years ago the museums made headlines with the acquisition of 2,000 Mapplethorpe photographs, plus the artist’s huge archive. Reportedly valued at $38 million, it was largely a gift of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, based in New York, and a partial purchase with $3 million in funds from the David Geffen Foundation and the Getty Trust.

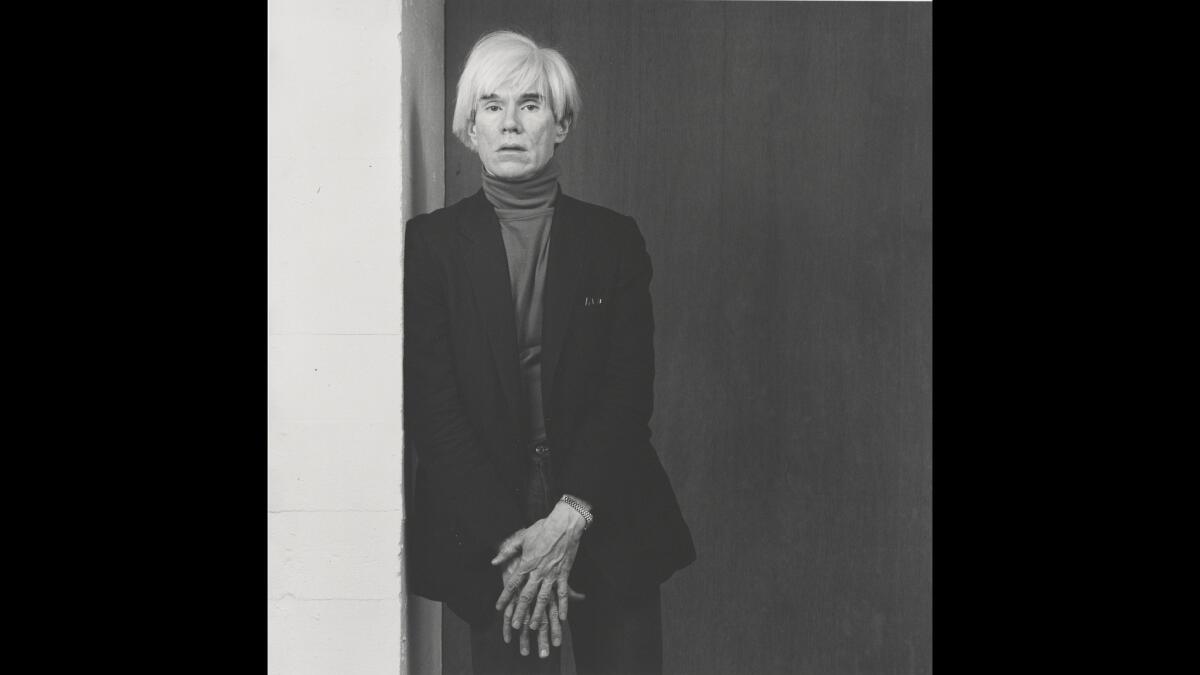

“Andy Warhol,” 1983. Gelatin silver print.

The move upset Mapplethorpe followers in New York, since the Queens-born artist had always lived there. But Los Angeles, a world center of photographic scholarship, clearly had the desire and capacity to care for the material.

Opening March 15 at the Getty and March 20 at LACMA, the exhibition features more than 300 photographs. Some have never been shown. One book of the hefty two-volume catalog focuses on “The Photographs,” the other on “The Archive” — student work, drawings and sculptures, plus 120,000 negatives, 6,000 contact sheets, letters, magazines, source material and other ephemera.

The show, divided between the venues, will travel to museums as far-flung as the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in Canada and the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia, after closing in L.A. July 31.

Such an outcome was unimaginable 25 years ago. The animus directed toward Mapplethorpe’s art and its complex homosexual frames of reference was partly simple scapegoating — a fearful shriek emblematic of the era’s AIDS hysteria. The incidence of the disease, then very much a medical mystery, increased rapidly through the 1980s, peaking in the early 1990s. It became a refracting lens focusing a deep vein of homophobia running through American life.

The vulgar moralizing hit an astonishing low in summer 1989, when the New York Times published a 2,500-word Sunday screed by its former art critic, Hilton Kramer. He asserted that public presentation of Mapplethorpe’s art posed a threat to social stability. Homosexuality was OK, the argument essentially went, as long as it stayed in the closet.

As the Times’ former columnist Sydney Schanberg once explained, the newspaper “interprets the establishment to the establishment,” so Mapplethorpe’s artistic reputation took a major hit. Nothing quite like it had been seen since the Victorian days of postal inspector Anthony Comstock, who once got the NYPD to raid George Bernard Shaw’s 1905 production of “Mrs. Warren’s Profession” for focusing on prostitution.

But don’t expect frenzy or fainting couches now at the Getty and LACMA. Conservatives long ago lost the establishment’s battle in the culture war.

1989 marked the start of a major transition in Americans’ world view. Mapplethorpe died on March 9. Eight months later, on Nov. 9, East German leader Egon Krenz announced the opening of a crossing point between East and West Germany. The Berlin Wall came tumbling down.

As the international Cold War unraveled, a domestic culture war ramped up. When the Soviet Union disappeared and the “godless enemy” suddenly vanished, America fabricated a profane and offensive enemy within to compensate.

It couldn’t last. AIDS exposed the closet, humanizing its victims. Conservatism seeks to halt social evolution and return to a way of life that is disappearing, but it’s inevitably a lost cause. “Conservatives typically start the battles, and liberals almost always win them,” explained Boston University religion professor Stephen Prothero in this newspaper not long ago.

Mapplethorpe’s stature has changed dramatically. Dozens of books have been published on his images of flowers, portraits, the bodybuilder Lisa Lyon and the outlandish sex pictures. His biography has been chronicled and relationships charted between his photographs and everything from classical Greek and Roman sculpture to Andy Warhol’s Pop art.

His work is enthusiastically collected by private individuals and art institutions. Last year, the once-notorious 1980-81 “Man in Polyester Suit” — a torso of a black man wearing a gray suit and vest with his uncircumcised penis hanging out of his zipper — sold at auction for more than $387,000.

Timing was instrumental to the change. Coincidentally, the sesquicentennial of photography’s invention also fell in 1989.

The medium’s history was explored in the press and scholarly publications, and celebrations took place in myriad museums. For 150 years, photography had been an artistic stepchild, its own significant internal history separate but not equal to painting, sculpture or even newer forms such as installation and Conceptual art. The sesquicentennial helped change that.

So did Mapplethorpe. The sex pictures showed that photography was an inherently promiscuous art form.

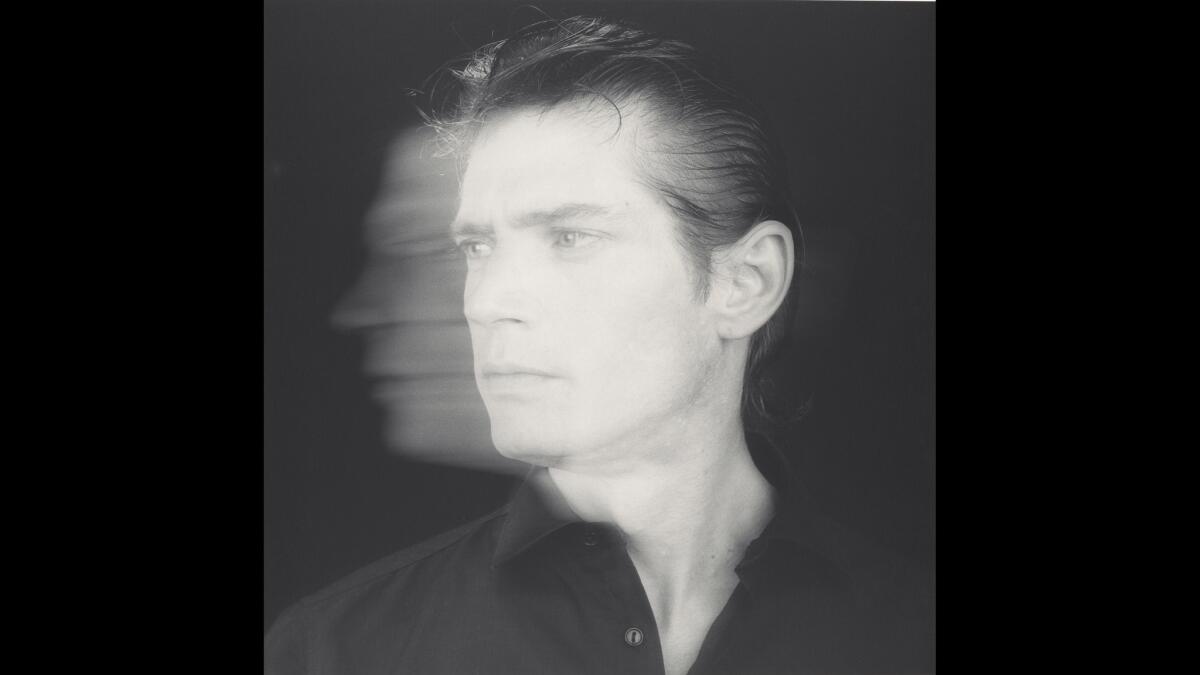

“Self-Portrait,” 1985. Gelatin silver print.

Before cameras, man-made images mostly represented the authoritative social class that held power. Most images were made to flatter or contest their patrons’ tastes.

Photography put an end to that. Precisely who could make and circulate pictures radically altered. The image-making door was opened to the untidy mob. Anyone, grandee or hoi polloi, could turn up in a picture. Mapplethorpe’s elegantly composed sex pictures made the point explicit.

Faced with photography’s widening challenge as the 20th century unfolded, the establishment could keep “the riffraff” at bay only by loudly proclaiming: Sorry, but photographs are not art. The fiction was impossible to maintain, however, as technology grew and diversified.

A market for photographs emerged in the 1970s, partly led by museum curator and art historian Samuel Wagstaff, who was also Mapplethorpe’s lover. (“The career Robert had would not have existed without Sam,” says writer and raconteur Fran Lebowitz in “Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures,” the finely textured documentary by Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato airing April 4 on HBO.) Wagstaff’s historically important collection of more than 25,000 photographs was acquired by the Getty Museum in 1984, becoming an anchor of its incomparable holdings. A selection will be on view in conjunction with the museum’s Mapplethorpe show.

------------

For the Record

An earlier version of this article said Samuel Wagstaff’s collection consisted of more than 2,500 photographs.

------------

Mapplethorpe’s career as a mature artist lasted barely a dozen years. It started with his initial 1977 exhibition at New York’s Holly Solomon Gallery and ended with his death just 12 days after “The Perfect Moment” opened at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art. He was 42.

Throughout those years, he made self-portraits. They play a significant role in the upcoming extravaganza.

The cover of the show’s photographs catalog features a remarkable self-portrait taken shortly after his 1985 AIDS diagnosis. Turning his head as the shutter was open and the exposure made, a classic 3/4 portrait blurs into a profile view. He fades away.

The blurred head also recalls Renato Bertelli’s 1933 sculpture, “Continuous Profile of Mussolini,” in which the dictator’s head seems to spin like a top. Mapplethorpe owned a cast of it. His self-portrait shows him as he was and as the fictional monster he was made out to be.

The artist’s greatest self-portrait is the grimmest one. Mapplethorpe, for what he knew would be his final chance to represent himself, went for visual opulence — and for posterity too. The startling photograph is a platinum print, a stable and durable darkroom technique that offers the widest tonal range.

Mapplethorpe’s head — careworn face, hollowed cheeks and furrowed brow together showing the cruel physical damages of AIDS — is juxtaposed with his right hand, which firmly grasps a wooden cane just below a knob carved into a human skull. Ravaged head and resolute hand float in a luxurious field of blackness.

When the photo was made, Mapplethorpe’s health was in serious decline. Wagstaff had died, and the artist arranged to sell his landmark collection of late-19th century silver and established a foundation whose initial mandate was to further the recognition of photography as art — including his own.

Ambitious he was. The self-portrait’s two, formally different, death’s heads show how.

Mapplethorpe’s skull-like face is gently fuzzed, slightly out of focus, as if a phantom hovering in the background. Up front, by contrast, his firm hand and carved cane are crisp and clear. The juxtaposition recalls the 19th century vogue for spirit photographs that early tricksters made, doctoring negatives to makes the dead seem to appear in the presence of the living.

The artist’s hand supersedes his ghost in this exquisite spirit photograph. Ars longa, vita brevis — if art is long and life short, he was prepared. Mapplethorpe had wrapped a fist around art, and he held it fast.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.