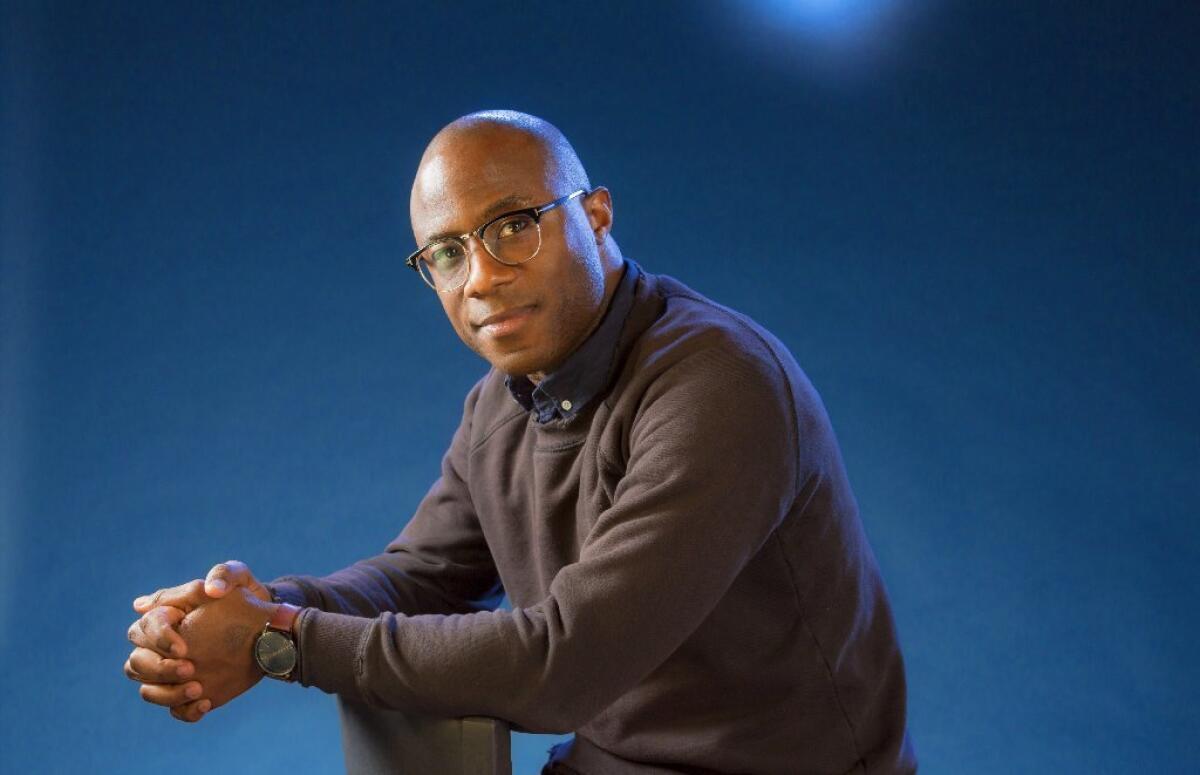

‘’Moonlight’ changed me,’ says director Barry Jenkins of his emotional story of acceptance

- Share via

On his way to the AMC Loews Lincoln Square on the day “Moonlight” opened in New York City, writer-director Barry Jenkins remembered thinking, “The AMC Lincoln Square? This movie?”

“Moonlight” was also showing at the art house bastion Angelika Film Center, a venue Jenkins figured to be more in line for his drama depicting three periods in the life of a young black man struggling with and ultimately learning to accept his gay identity. Jenkins knew the Angelika crowd from his first movie, the tender love story “Medicine for Melancholy,” released in 2008.

So, curious, Jenkins went to the AMC multiplex in New York’s Upper West Side, wandered into the 780-seat theater and looked out and saw a lot of faces he didn’t expect to find. It was racially mixed. There was a lot of gray hair. And, afterward, everyone stuck around for the Q&A, showing an interest in the film’s story and characters that went way beyond being polite.

These people really cared about this film.

That passion for “Moonlight,” one of the year’s brightest indie movie success stories, began when it screened at fall film festivals in Telluride and Toronto. Jenkins immediately realized his expectations might have been a bit modest.

“I was walking around Telluride 45 minutes after the first screening and I noticed this 65-plus-year-old white guy — North Face jacket, gray hair, very masculine-looking dude — and he’s just staring at me as I’m walking by,” Jenkins recalls. “So I ask him, ‘Are you all right?’ And he starts to speak … and he can’t speak. And the only thing I could do was to give this guy a hug. And he’s just sobbing in my arms.”

Jenkins, telling the story over a long dinner at the Grand Central Market in downtown Los Angeles, stops and shakes his head. “I can’t account for that North Face guy. Just as I couldn’t have pictured grown straight men having the reaction they’re having to these characters. I think this movie is a test of people’s empathy at this moment in America’s history. And right now, I have to say I’m encouraged by the response.”

“Encouraged” is probably selling short Jenkins’ mood these days. The filmmaker, who turned 37 this month, spent eight years trying to follow up his first film, a period marked by a prolific amount of work that didn’t get produced (two years alone on an epic combining time travel and Stevie Wonder), along with a few short films, shooting branded content for companies like Bloomingdale’s and Facebook and an unsatisfying stint as a staff writer on the HBO series “The Leftovers.”

“I look back and yeah, I should have done more,” Jenkins says of a time he describes as a “little bit of a dark patch.” “I wish I had done more. That’s time I can’t get back.”

The problem, says Adele Romanski, Jenkins’ friend from their days at Florida State University’s film school and a producer on the film, was a combination of bad timing (“Medicine,” his debut feature, arrived at the same time as the recession) and a self-doubt that crept in through the years. “Suddenly, you’re not new and exciting any more,” she says.

Finally, in January 2013, Romanski told Jenkins that she was going to “force him to make something.” The two started video chatting twice monthly, spit-balling ideas, narrowing choices, ultimately landing on Tarell Alvin McCraney’s play, “In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue,” and a James Baldwin novel, “If Beale Street Could Talk,” a love story set in Harlem. After polling his friends to find “the most boring city in Europe during the summer,” Jenkins left for Brussels, where he wrote the screenplays for both in six weeks.

The connections between McCraney’s play and what ended up becoming “Moonlight” are, as Jenkins puts it, “nuts.” Both men grew up in Miami’s impoverished Liberty Square neighborhood. McCraney’s mother died from an AIDS-related illness. Jenkins’ mother is HIV-positive. Both women had been intravenous drug users. Where they diverge: McCraney is gay; Jenkins is straight. And that was a “hurdle,” Jenkins says, when contemplating whether he was the right person to tell the coming-of-age story of a young gay man.

“I had some ambivalence because I thought, ‘Oh, this has to come from a first-person perspective,’” Jenkins says. “And I don’t know what it’s like to kiss another man. I don’t know what it’s like to not kiss another man because of what society thinks.”

But Jenkins felt like he knew so much about Chiron, the movie’s protagonist, from the “inside out” that he could step inside his shoes and use his empathy and passion to advocate for the importance of this character’s journey. He could be “fully present in the moment,” a state of mind he talks about again and again in conversation, an openness to finding specific truth and feeling that, Jenkins’ actors say, makes his movies relatable to anyone watching them.

“He always says he’s about making the film that’s in front of him,” says Mahershala Ali, who plays Juan, Chiron’s surrogate father in “Moonlight.” Ali points to one of the movie’s most cherished scenes, where Juan teaches Chiron to swim. Finding the heart of that interaction, which resonates as a joyful, peaceful moment of empowerment and liberation, took an hour spent in the Pacific Ocean, shifting between Juan’s teaching and Chiron’s discovery until the perfect balance was achieved.

Likewise, the scenes between Chiron and his drug-addicted mother were altered because once Jenkins found himself back in his old neighborhood, shooting material based on his childhood memories, he felt the words weren’t going far enough. He changed a scene in the movie’s middle section to give the audience a stronger sense that Chiron was seeing his mother in the throes of addiction for the first time and not being able to deny that reality. A third-act scene between mother and son at a rehab center changed because Naomie Harris, the actress playing, essentially, Jenkins’ own mom, couldn’t light her cigarette.

“That scene is meant to be an apology, but the actual apology is not written into it,” Jenkins says. “When Naomie couldn’t figure out how to light the cigarette, I saw an opportunity. I whispered to Trevante [Rhodes, who plays the adult Chiron] between takes, ‘Reach over and light it for her and give it back to her.’ And it just opened everything up. It was like waterfalls.”

When that scene finished, Jenkins turned from his monitor to find the entire crew in tears. At first, he thought, “Why are you crying? We’re professionals.” Then he realized he was just preventing himself from crying because he had to stay focused, particularly because they were going off script.

“They cried every damn take of that scene,” he says.

Jenkins took a break between the festivals and promoting “Moonlight,” spending 10 days directing an episode of “Dear White People,” the upcoming Netflix series based on Justin Simien’s 2014 film. He’s set to re-team with Romanski and Plan B Entertainment on a limited TV series adaptation of Colson Whitehead’s bestselling novel, “The Underground Railroad.” But that’s a massive undertaking. And Jenkins would like to find himself back on a film set — a place where he says he’s the best version of himself — sooner than later, so he’d like to make the Baldwin adaptation, “If Beale Street Could Talk,” first.

“To go another eight years again would be awful, totally awful,” Jenkins says. “But that’s not going to happen. ‘Moonlight’ changed me. To see people so moved by this movie inspires me to find something else to offer. And maybe the next one touches only five people or maybe just one person. To me, you know, that would still be worth it.”

See the most-read stories this hour »

Twitter: @glennwhipp

ALSO:

What can’t a little ‘Moonlight’ do?

Gotham Awards: Big night for ‘Moonlight’

Gold Standard: ‘Moonlight’ continues to exceed expectations, leading the way at the Spirit Awards

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.