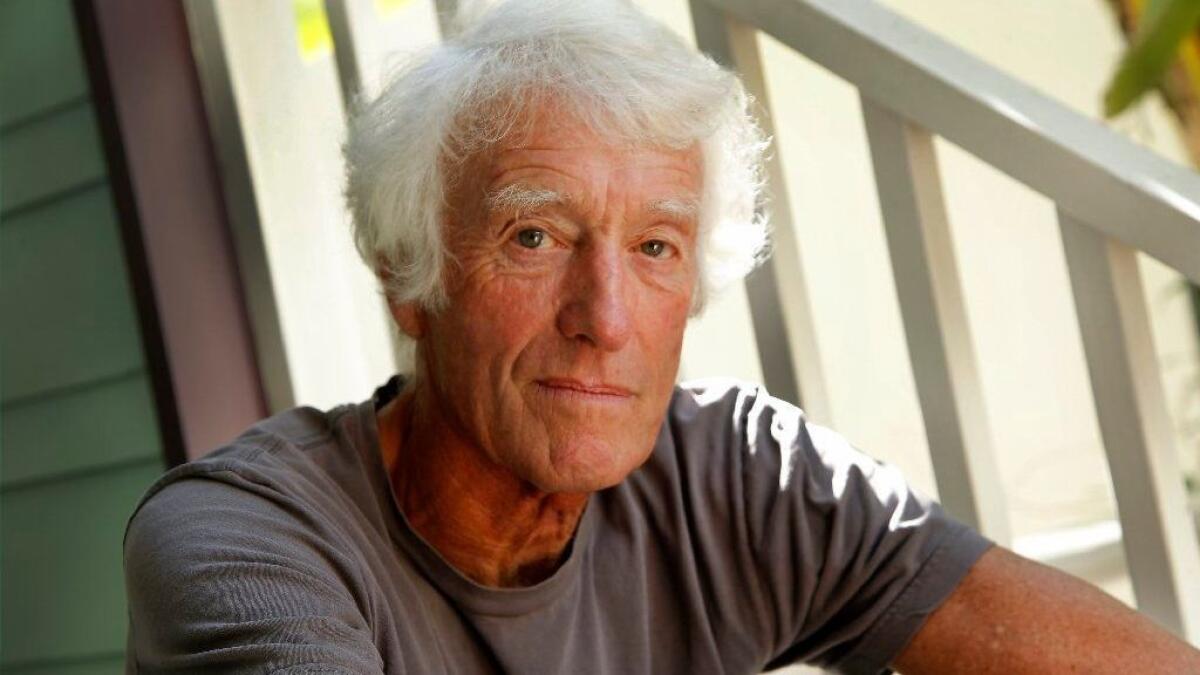

Roger Deakins has 14 Oscar nominations and is still seeking his first win

- Share via

One of Hollywood’s undisputed masters of light, British cinematographer Roger Deakins earned his 14th Academy Award nomination this year for his typically dazzling work on “Blade Runner 2049.” Yet Deakins, 68, has never actually taken home an Oscar statuette.

Fans of his work in such varied films as “Sid and Nancy,” “Dead Man Walking” and “The Big Lebowski” may call this an almost criminal oversight. But Deakins — whose work on “Blade Runner” has earned awards this year from the British film academy and the American Society of Cinematographers, and makes him an Oscar front-runner — isn’t one to complain.

“That doesn’t really bother me,” he said last week by phone from New York, where he is working on the film adaptation of the bestselling novel “The Goldfinch.” “I’m just proud to still be doing the job, really, and happy doing it.”

Here, he looks back on five of the films that earned him Oscar nominations.

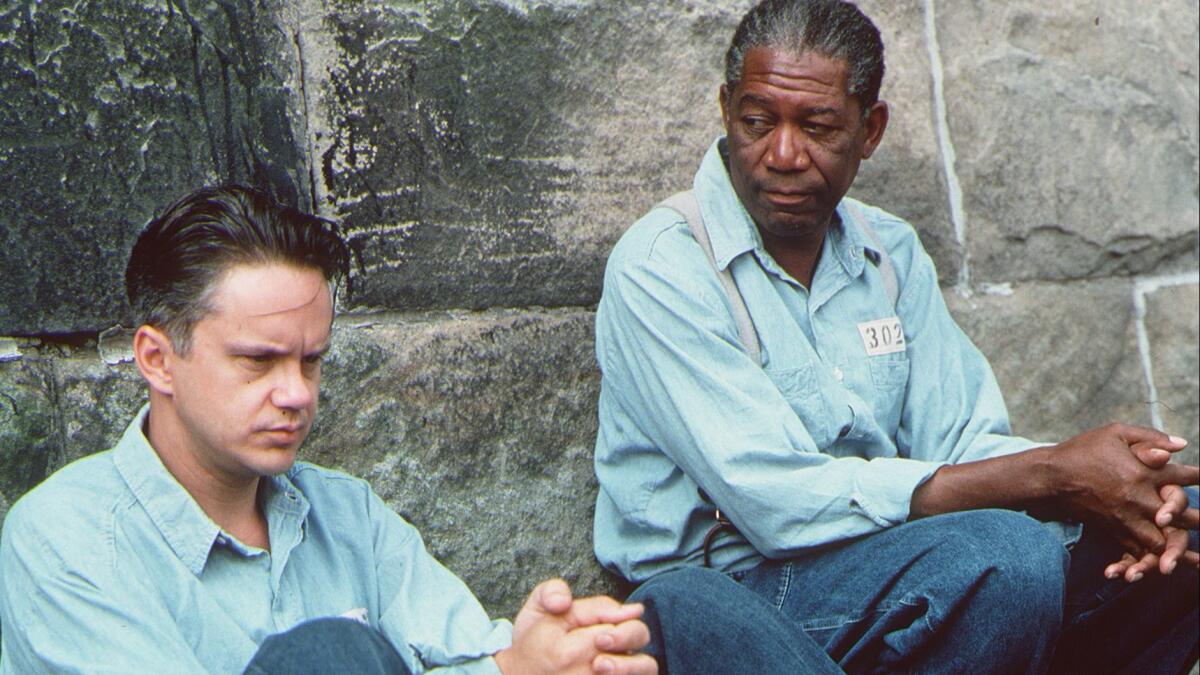

The Shawshank Redemption (1994)

Deakins, who’d started his cinematic career in documentaries, brought his naturalistic style to Frank Darabont’s adaptation of a 1982 Stephen King novella about a man unjustly sentenced to life in prison for murder. A box office dud that became a hit on home video, “Shawshank” earned Deakins his first Oscar nod and would go on to become one of the most beloved films of the 1990s.

What attracted me to it was the story — it was a brilliant script — and then, of course, the casting. But the challenge is always to immerse the audience in that world.

You could say that a prison isn’t that visually interesting but it actually was. Less is always more — that’s my mantra. In so many movies now, the camera is always moving, the light is always glittering. “Shawshank” was the antithesis of that, really.

I remember they released the movie [in theaters] twice, thinking maybe there was some marketing problem, and it still didn’t get any traction. But then the video release was kind of crazy. I wasn’t surprised that it was discovered. I think it’s a good film.

Fargo (1996)

Deakins received his second Oscar nomination for the Coen brothers’ darkly comic crime film, which marked the third of his 12 collaborations with the Coens. Deakins’ cinematography beautifully captured the bleakness of the winter landscape of the upper Midwest, as in one particularly memorable shot looking down at hapless car salesman Jerry Lundegaard (William H. Macy) as he trudges through an empty parking lot to his car.

The Coens are just so meticulous and their craftsmanship and their ideas are so brilliant, and every film they do is so different. I did “Barton Fink” with them and then I did “The Hudsucker Proxy,” which wasn’t very successful — for the life of me, I don’t know why, because I think it’s quite a brilliant film.

Then they said to me they were going to do this small film and I might not be interested because it was no money and all this — and it was “Fargo.” I was like, “You’re kidding, guys.” It was one of the best and most memorable experiences I’ve ever had on a film.

For that shot of Jerry going to his car, we had like 100 extras with cars that day that were originally going to fill the parking lot. We were at the top of this tower looking at this shot, and I just turned to Joel and I said, “Are you sure you want any other cars in this shot?” He just looked at me said, “Oh, right.” We all reacted to the image of this lone car, this lone figure, the footprints he left in the snow and the fact that there’s nothing else there.

The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007)

Showing his versatility, Deakins was Oscar nominated the same year for director Andrew Dominik’s revisionist western and the Coens’ bloody “No Country for Old Men.” Though few saw “Jesse James” in theaters, the slow, contemplative film featured what many consider Deakins’ most stunningly beautiful work, with his camera patiently lingering on the landscape as well as the faces of co-stars Brad Pitt and Casey Affleck.

I love westerns — Howard Hawks, Sam Peckinpah — and I’ve been very lucky to do a few of them. For me, “Jesse James” was a tone poem, similar to [the 1997 Tibet-set epic] “Kundun,” which I shot for Marty Scorsese — this melancholy poem. It was such a great opportunity to do a western with that kind of style and feeling.

I used to do a lot of rock videos when I was starting out. I remember I shot Muddy Waters and B.B. King and they were so magnetic, you didn’t want to move the camera. You stay in a close-up and just shoot the guy doing his thing. If you believe in the material and the performance, then you don’t need to do a lot, frankly.

It’s always disappointing when a movie doesn’t reach a wider audience. But on the other hand, when I meet students and enthusiasts at screenings and they say, “ ‘Jesse James’ really affected me” or “ ‘Jesse James’ is why I want to be a cinematographer” — you only have to have a couple of comments like that and it makes up for all those people that didn’t go to the cinema to see it for whatever reason.

Skyfall (2012)

Having never shot an action film, Deakins was initially wary when director Sam Mendes first approached him about working on the 23rd installment in the James Bond franchise. But his elegant, kinetic cinematography on the film would earn him his ninth Oscar nomination.

I’d watched Bond movies and they’re fun but, to be honest, I wouldn’t say I was much of a fan. But I had worked with Sam twice by then and the first film I did with him, [the 2005 war drama] “Jarhead,” I think is probably one of the best films I’ve worked on.

When Sam rang me the first time about “Skyfall,” he said, “Don’t put the phone down. Just hear me out.” I remember we went for a walk on the beach in L.A. to talk about it and he said, “OK, it’s a Bond movie and it’s going to have action and this, that and the other. But I want to do more with it and make it a character study.” He persuaded me.

I was nervous at the beginning but I really enjoyed it and I was glad I did it. I think he took that franchise and did something with it that was much more emotionally engaging. Sam went on to do another Bond film [2015’s “Spectre”] but I was quite honest with him and said I didn’t really want to do another one, which was a shame because I really love working with Sam.

Blade Runner 2049 (2017)

As a fan of director Ridley Scott’s original 1982 neo-noir sci-fi film, set in a dystopian future in which humans and androids live side-by-side, Deakins was excited about the idea of working on the long-discussed sequel. But both he and director Denis Villeneuve were very aware of the risks of trying to follow in the footsteps of a classic.

Denis and I talked about that and we both felt very much the same thing. But the thing was, it’s different. It’s not Ridley doing it — it’s Denis doing it. It’s the same world, 30 years later, but this was Denis Villeneuve’s film. The story is more expansive than the original in that you see more of the city, you see outside the city, you see more environments. So it was about creating the sense of the world.

For me, one of the most powerful science-fiction films is Andrei Tarkovsky’s [1972 movie] “Solaris.” Tarkovsky creates a world that is falling apart — the spaceship is retro and dirty and unkempt — and the way he does it, it’s totally real. It’s the most beautiful film because it totally takes you in. We were trying to do that a bit in “Blade Runner” with the [holographic] character of Joi. You could have made her very effects-y but we pulled back from that and said, “No, we want the audience to empathize with her rather than just be titillated by some effects-y thing.”

Sometimes I get a kick out of the seemingly simplest things. In the opening scene, you go into this little farmhouse and there’s just this little bit of ambient light coming in from these windows. It was like something from [the 1985 western] “Pale Rider” — you go into this dark room and your eyes have to get adjusted to it. It was so minimal, and I thought it was quite successful.

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.