Pedro Almodóvar’s deeply personal ‘Pain and Glory’ could bring his first Palme d’Or at Cannes

- Share via

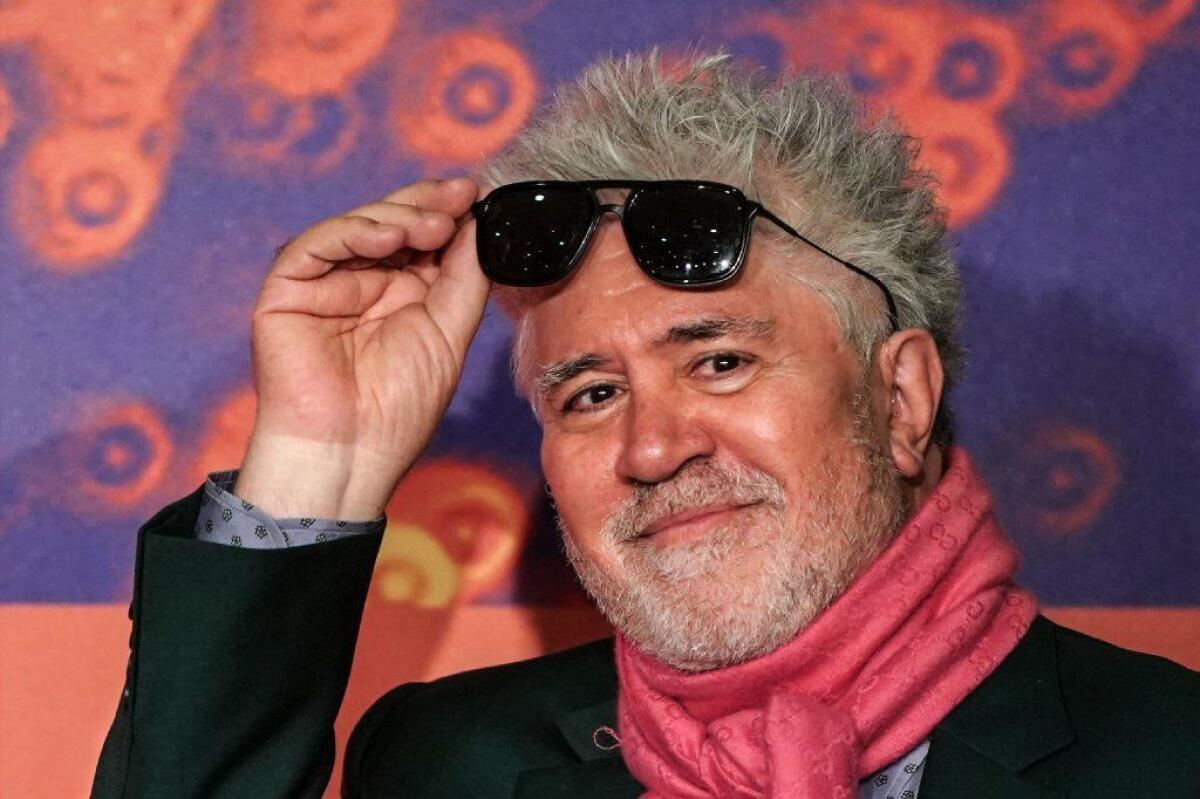

Reporting from Cannes, France — “This is the game,” Pedro Almodóvar says, his eyes positively twinkling as I apologize about asking an obvious question. “You will ask it and I will answer as if it’s the first time.”

The Spanish master director is sitting in a sheltered corner on a quiet hotel rooftop, enjoying the calm before the storm that is the Festival de Cannes.

“It’s exhausting and exciting,” he says, in advance of his latest film’s official festival premiere, “and by the end, you are completely destroyed.”

But it is early now, and Almodóvar, both serious and playful, has the time and leisure to talk about that new film, the emotionally potent “Pain and Glory,” starring frequent collaborator Antonio Banderas and the director’s sixth film in Cannes competition.

And although he won an original screenplay Oscar in 2003 for “Talk to Her” and his “All About My Mother” claimed the foreign language film prize in 2000, Almodóvar has yet to win Cannes’ top prize, the Palme d’Or.

Already playing in Spain and set to open in the U.S. on October 4, “Pain and Glory” concerns an aging filmmaker at a crisis point in his life, a protagonist the 69-year-old Almodóvar has called “a director with his aches and pains.”

But it’s also told in a style — “more drama than melodrama” — that the director recognizes as very much of a departure for himself.

RELATED: Pedro Almodóvar’s ‘Pain and Glory’ hands the Cannes competition its first triumph »

“Melodrama is a genre that I love in every place,” Almodóvar says. “Argentina, Mexico in the 1950s and ’60s, classic Hollywood films starring Joan Crawford and Bette Davis. Big huge melodrama with this kind of flamboyance is a lot of fun.”

But with “Pain and Glory,” he felt “a fascination with being much more austere. That attracted me because I didn’t do it before, and it’s also a question of the passage of time. This is because I’m getting old.”

The story involves solitary director Salvador Mallo (Banderas) who is thinking of leaving filmmaking because he is in intense and constant physical pain due to chronic back problems. A chance meeting leads Mallo to reconnect with a former star he has fallen out with, the heroin-using Alberto Crespo (Asier Etxeandia).

That meeting leads to unexpected situations and memories of a vibrant past with his mother (Penélope Cruz) that culminate in an emotionally buoyant resolution the earlier pain and loneliness would not anticipate.

Hearing all this — and knowing that Almodóvar like Mallo is gay, suffers from back pain and is considered the great Spanish director of his generation — you might label this film as autobiographical. According to the writer-director, however, it both is and isn’t.

“I’m always inspired by reality, something I read somewhere or heard on radio or television, and this time my own reality was the start,” Almodóvar says. “There is a lot of myself there, but some things belong completely to my life and some do not but could have been.

“I never had heroin but I was surrounded by people who did. I did not live in a cave as the child Salvador did, but my family lived in precarious conditions and I discovered those caves (in Paterna in Valencia) when I was shooting ‘Bad Education’ 14 years ago and have been wanting to use them in a film.

“The story of my mother giving specific instructions about being prepared after death came directly from my life, but it happened to my sister. I stole many memories from my brother and sisters.”

More than that, “from the moment I start writing, that creates a distance from the reality. And once I began shooting I don’t feel it’s me at all.”

For instance, Mello’s apartment, constructed in a Madrid studio, is almost a replica of Almodóvar’s residence in the same city. “The paintings are mine, more than 50% of the furniture is mine. My crew even asked me how it felt to go home at night to the same place I was shooting, but I didn’t have that feeling at all.”

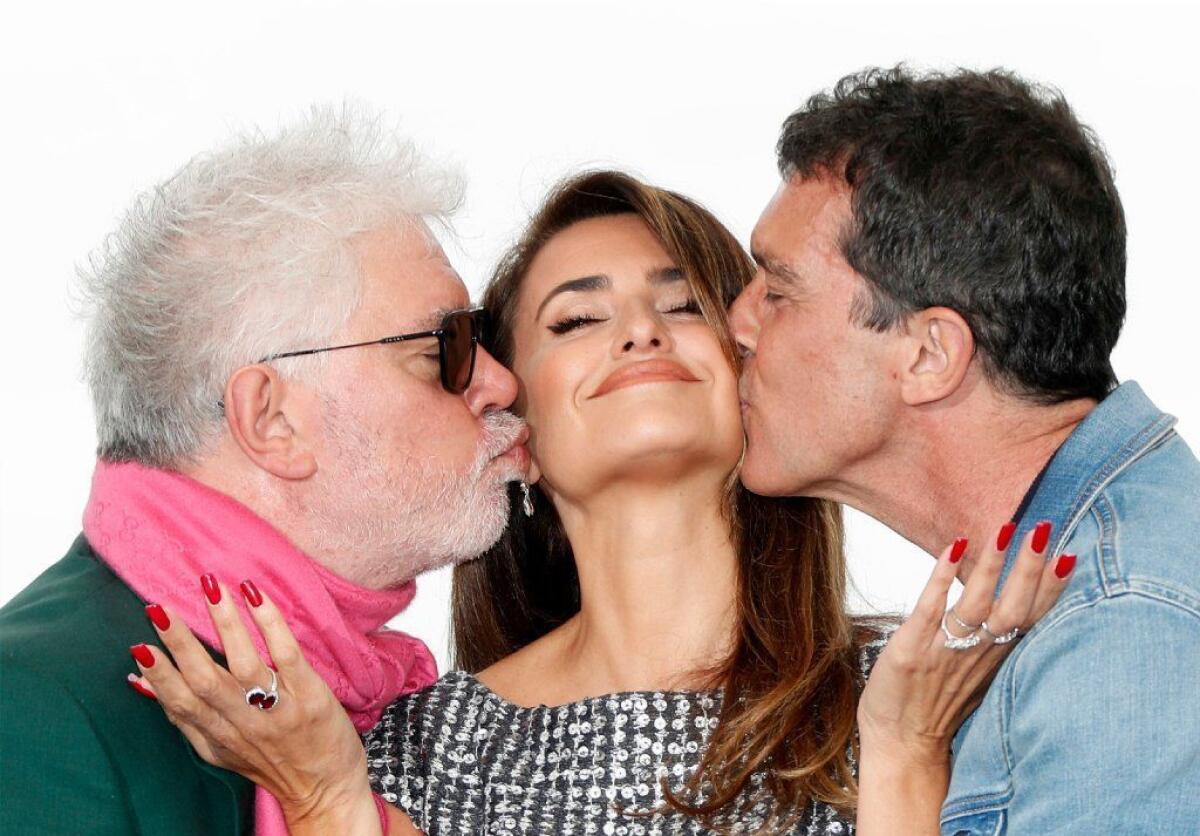

Equally singular and complex is Almodóvar’s relationship with his star. He and Banderas have made eight movies together, starting with 1982’s “Labyrinth of Passion,” but there is a twenty-plus year gap in their collaboration, and therein lies a tale.

“Usually there is an advantage if you keep on working with the same actors, you already have a common language, but in the case of Antonio it is different,” Almodóvar says.

“In the years between ‘Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!’ (1989) and ‘The Skin I Live In’ (2011), he changed a lot as an actor. Not as a person — since the 1980s he has been my little brother and we are very close — but he became a Hollywood star.

“It was a kind of miracle, I was very happy for him and very inspired too — he was the first Spanish star to walk into Hollywood and play the main character. But without criticizing that period, the kinds of movies he did were very different from those he did with me.”

FULL COVERAGE: Cannes Film Festival »

When the two reunited for “Skin,” “we had to adapt to one another. Our ideas about character were very different. It was not a struggle or a fight, we love each other too much for that, but there were differences we didn’t have in the past.

“So when I sent him the script for ‘Pain and Glory,’ I said, ‘We shouldn’t repeat that situation. We are too old, and too good [of] friends.’ And he said, ‘Don’t worry, I will put myself in your hands,’ and he did.

“I told him what I needed from him, just the opposite of the kind of passion and bravura he did in Hollywood. I needed someone frail. He did a brilliant job, I was impressed how far he went into these new gestures, gestures that were minuscule not big.”

And although he didn’t know it at the time, “Pain and Glory” would go on to enthusiastic notices when it played in the Cannes competition on Friday night.

“The reviews in Spain were incredible for him,” the director said, “And I hope Cannes is also generous.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.