The wonderful, improbable Palme d’Or triumph of Hirokazu Kore-eda’s ‘Shoplifters’ at Cannes

- Share via

On the last day of every Cannes Film Festival, word begins to leak out about which filmmakers from the competition have been called back for the closing-night awards ceremony. Many of us already knew, going into Saturday night’s show, that Pawel Pawlikowski’s “Cold War,” Alice Rohrwacher’s “Happy as Lazzaro,” Spike Lee’s “BlacKkKlansman,” Nadine Labaki’s “Capernaum” and Hirokazu Kore-eda’s “Shoplifters” were certain to go home with awards, though which film would win what remained a mystery.

Festival juries are notoriously difficult to predict, but several other critics shared my hunch that the Palme d’Or, the festival’s top prize, would go to either “Capernaum” or “BlacKkKlansman.” Both were among the most enthusiastically touted films in the competition, and they offered the jury a chance to anoint either Labaki, a Lebanese director who had just launched herself into the big leagues, or Lee, a veteran American auteur who had famously (and angrily) lost the Palme nearly 30 years ago for “Do the Right Thing.” Would they go with the striking new talent or the overdue veteran?

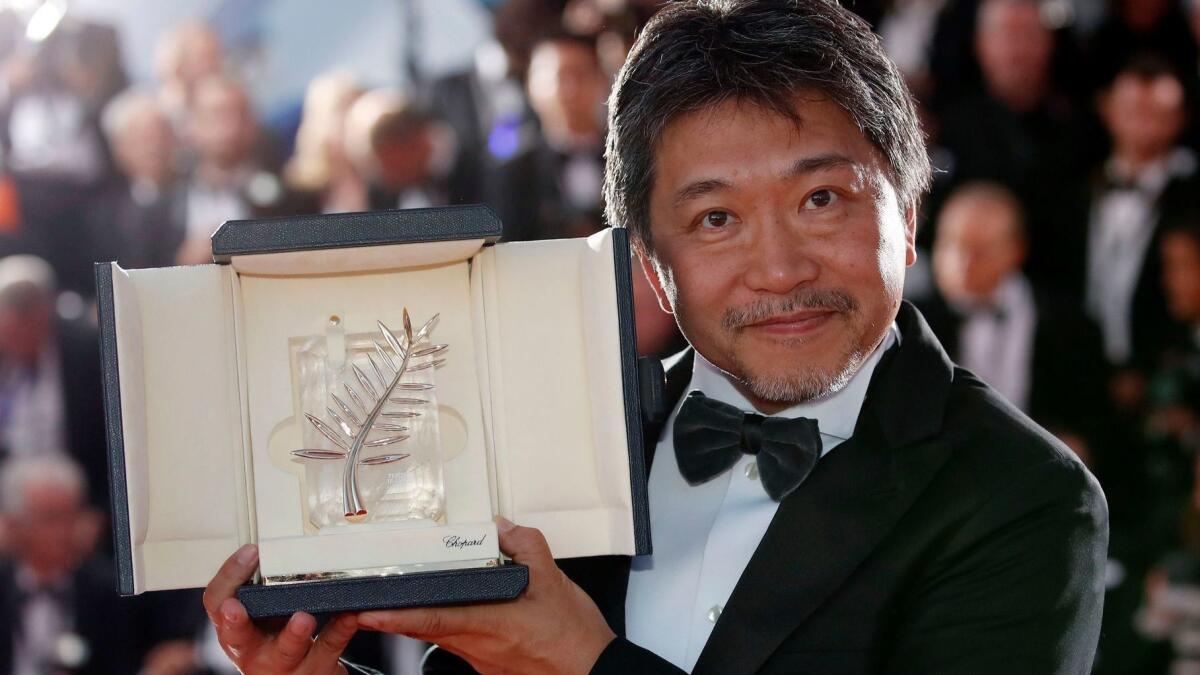

In the end they chose the overdue veteran, though not the one some of us were expecting. In a development as startling as it was altogether marvelous, the jury president, Cate Blanchett, announced that the Palme d’Or had gone to Kore-eda’s “Shoplifters,” one of the quietest, loveliest and most emotionally enduring films in the competition.

Did anyone see this coming? To judge by his genially shell-shocked reaction, Kore-eda himself certainly didn’t.

If anything, this beloved, prolific Japanese auteur had pulled off an upset as stealthy and light-fingered as his movie, which follows a makeshift family of supermarket thieves dwelling in cramped but loving quarters. A tender ensemble piece whose skillful performances dovetail into a perfectly symphonic whole, “Shoplifters” is a work of such emotional delicacy and formal modesty that you’re barely prepared when the full force of what it’s doing suddenly knocks you sideways.

Like so much of the director’s work, “Shoplifters” was so unobtrusive in its mastery that it seemed destined to be taken for granted, much like the director’s four previous Palme contenders: “Distance” (2001), “Nobody Knows” (2004), “Like Father, Like Son” (2013) and “Our Little Sister” (2015). Mais oui, another lovely humanist marvel from Kore-eda. What else is new?

There were other factors at play too. Being the first Cannes of the post-Harvey Weinstein era, the festival was dominated by discussions of gender parity and on numerous occasions became a bold platform for the #MeToo movement. Never was this more powerfully achieved than at the closing ceremony, when the actress-director Asia Argento took the stage and delivered a fearless speech excoriating Weinstein, the festival that had been “his hunting ground” and those in the theater who had yet to be called to account.

It was the kind of stunning, searing moment that makes any segue to the business of awards seem awkward at best, tacky at worst. In other words, it was emblematic of an industry trying to celebrate its best and brightest with one hand and holds its sins up to the light with the other.

Even before Argento left her indelible mark on the awards ceremony, many had theorized that Blanchett’s jury — perhaps the most scrutinized and second-guessed jury in recent memory — would be particularly keen on giving the Palme to one of the three films in the competition directed by women. To do so would be a small step toward righting the representational balance of a festival that has only awarded the Palme to one female director, Jane Campion. (Her 1993 film, “The Piano,” shared the prize with Chen Kaige’s “Farewell, My Concubine.”)

Cannes 2018: Read Justin Chang’s full diary from the annual film festival »

That was one reason, though hardly the only one, that many were predicting Palme glory for Labaki’s “Capernaum,” her third feature after “Caramel” and “Where Do We Go Now?”

A formally ragged, emotionally harrowing slab of Lebanese neorealism about a young boy who tries to sue his parents for bringing him into a world of unbearable cruelty and poverty, “Capernaum” sent a jolt of emotion through the festival when it premiered Thursday night. Already tipped as a strong contender for the foreign-language film Oscar (it will be released in the U.S. by Sony Pictures Classics), it offered the jury a popular, broadly accessible choice for the Palme.

A subtler, more beguiling Palme possibility would have been “Happy as Lazzaro,” a bittersweet fable from the Italian writer-director Rohrwacher (who won the festival’s Grand Prix, or second prize, for her 2014 film, “The Wonders”). Following a young innocent whose selfless compassion throws the cruel machinery of capitalism into stark relief, the movie became an early critical favorite with its sly, mischievous fusion of magical realism and classic humanist storytelling.

It was unfortunate that only three of the 21 films in competition were directed by women (the third was Eva Husson’s generally reviled war drama, “Girls of the Sun”), which shows that more work needs to be done on the festival’s part and, more importantly, on the part of the global film industry.

Still, an impressive two of the three did end up winning awards Saturday night: “Capernaum” took the jury prize, effectively third place, while “Happy as Lazzaro” shared the screenplay award with “3 Faces,” an ingenious fusion of mystery and social critique from the Iranian director Jafar Panahi (who wrote the script with Nader Saeivar).

In singling out “Capernaum” and “Happy as Lazzaro” for awards, Blanchett’s jury succeeded in recognizing two of the competition’s more popular films while sending a clear message of support for female filmmakers. But looking elsewhere for the Palme sent a message, too, defusing any possible charges of tokenism and alerting the outside world that this jury would ultimately hew to its own path.

Late into the ceremony, with only two films and two awards remaining, I assumed that path would lead to “BlacKkKlansman.” The improbable true story of a black police officer who infiltrated the Ku Klux Klan in the early 1970s, Lee’s blisteringly funny, topically urgent drama, which ends with a fierce denunciation of white supremacy in Donald Trump’s America, felt like it might well be this year’s “Fahrenheit 9/11,” which won the Palme in 2004.

Giving top honors to one of the few American films in Cannes this year might even have helped the embattled festival restore its tarnished reputation as a dream destination for Hollywood blockbusters and awards-season hopefuls. Also, as a friend quipped: “Would you want to be on the jury that gave Spike Lee second place?”

But in the end, that’s exactly what they did. Kore-eda won, and there was a sweetness to his victory that transcended even the simple pleasure of seeing a great filmmaker receive the highest honor in world cinema for one of his very best movies. It took discernment, for one, to see the shared virtues of “Shoplifters” and “Capernaum,” both wrenching portraits of young children on the streets, but also to see that one had been dramatized with a more assured hand.

A win for “Shoplifters” also partially acknowledged the unusual strength of the Asian-directed films in competition, which included “Ash Is Purest White,” a gripping gangster melodrama from China’s Jia Zhangke, and “Asako I & II,” an emotionally astute romantic triangle from the Japanese newcomer Ryûsuke Hamaguchi.

Both were shut out of the awards, and so, most disappointingly, was “Burning,” a hypnotically unsettling psychological thriller from the South Korean writer-director Lee Chang-dong, which set an all-time record of 3.8 out of 4 stars on the Screen International critics’ panel (in which I was a participant).

Blanchett’s jury made impeccably smart choices for director (Pawlikowski for “Cold War”), actor (Marcello Fonte for Matteo Garrone’s “Dogman”) and actress (Samal Yeslyamova for Sergei Dvortsevoy’s “Ayka”), but they also clearly admired more films than they could accommodate. In addition to the tie for screenplay, they awarded a “Palme d’Or Spéciale” to the veteran filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard, whose “The Image Book” was the most abrasive and adventurous thing in Cannes by several light years — another of his dense, synapse-frying meditations on the decay of language, imagery and civilization as we know it.

Compared with that option, “Shoplifters” might seem in retrospect like an unusually safe, palatable choice. Amid the hype, rage and politically charged bluster that dominated this year’s festival headlines — over #MeToo, over Trump, over Netflix, over selfies — perhaps what this jury needed was the catharsis of a good, collective cry.

All well and good, but what makes Kore-eda’s movie so quietly devastating, the work of a master in full command of his art, is that its emotional rewards stem from a deep engagement with the world rather than a retreat from it. It’s the rare movie indeed that can unite a jury without even remotely smacking of compromise.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.