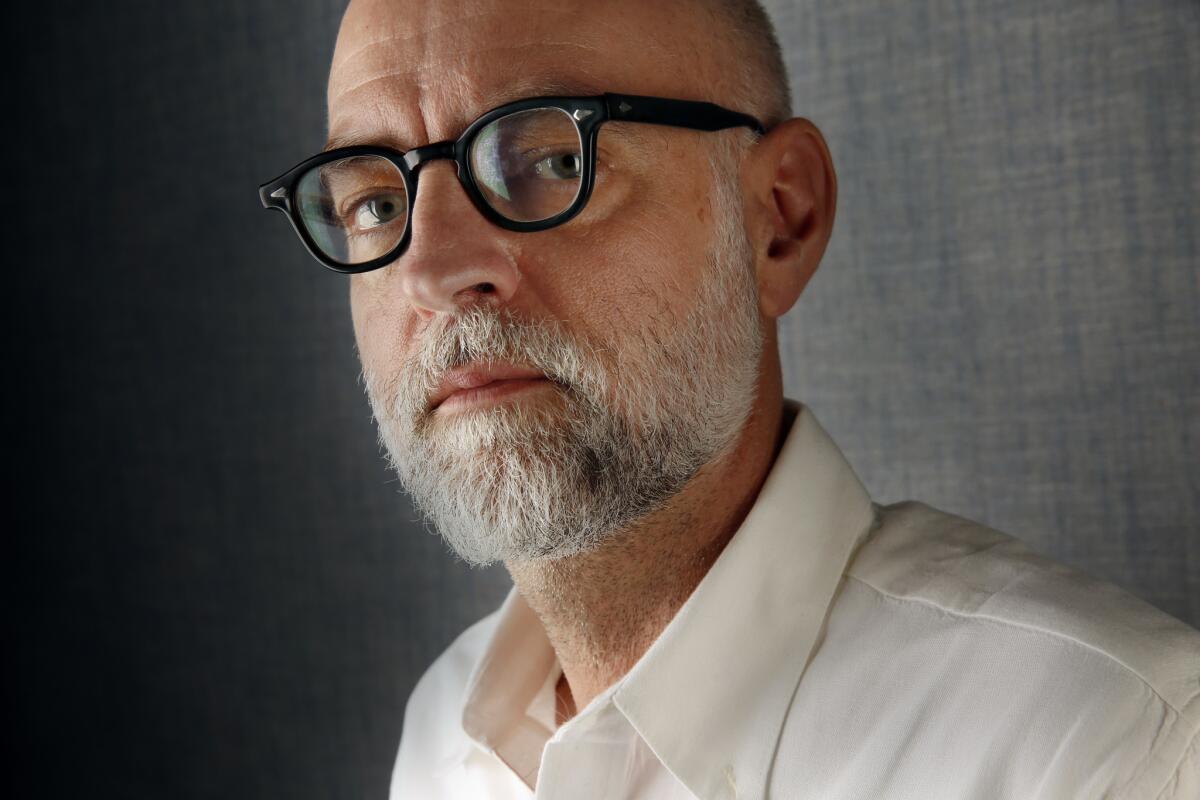

‘Wilson’s’ Daniel Clowes, patron saint of misfits and curmudgeons

- Share via

Reporting from NEW YORK — The graphic novelist Daniel Clowes was in the landmark Strand bookstore on a recent weekday, browsing the section of his chosen profession.

“Let me see if my signature is in here,” he said, flipping open a hardback copy of his time-travel romance “Patience.” “Oh, good,” he said upon seeing a clean title page. “I haven’t signed books here in a long time. If you see a signature it means the book has really been lying around.”

Not lying around is Clowes himself. Thirty years into an iconoclastic career, he could easily give his pen a rest. Instead he has continued drawing and scribbling.

Clowes released “Patience,” his longest book, last year, and is now working on the script for Focus. He also wrote the screenplay for the manically misanthropic “Wilson,” adapting his 2010 bestseller. As Craig Johnson’s movie hits theaters this weekend — starring Woody Harrelson as the crotchety wisdom-giver of the title and Laura Dern as estranged wife Pippi, more soulful and chatty than the sullen mess of the book — it brings to the screen one of the great modern literary cranks.

It will also bring back to the limelight one of the most influential of contemporary author-artists.

“A lot of kids think cartooning is something that pours out of your hand and onto the page. But it’s a lot of work to look like that,” said Clowes, in town to do some press and take in a city he once lived in. “People have approached me for a documentary. And I say, ‘You’re going to watch me at a desk, staring, then cursing every few hours. It really is a goofy job.”

His new Hollywood effort follows the title character on a series of tragicomic adventures. Wilson is the kind of person prone to walking up to laptop-tappers in cafes to complain about their lack of friendliness. After his father passes away (the story was inspired by the death of Clowes’ own dad), he sets out to find Pippi. She then shares a remarkable piece of family news that sets him on a further — but, as this is Wilson, benighted — quest.

“Wilson” is a book that many have described as best understood between the panels. The same can be said of its author, an affably deadpan type for whom little bits of color or opinion or anecdote, tossed in as low-key asides, paint the picture of the man uttering them.

Originally from Chicago, Clowes spent his formative student years at the Pratt Institute here, where he felt it was too rigid and theoretical (“I criticize, but it wasn’t their fault; I had to work up to that”). He has long lived in Oakland with his wife and 12-year-old son. He said that despite his reliable screenwriting career he spends almost no time in Los Angeles (“I realized early on they just want to meet you a few times to see you’re not crazy”).

That he was browsing in a high-end bookstore shouldn’t come as a surprise. Clowes may have a long IMDB page, but he is part of a small group of authors who have broadened the cultural perception of graphic novels — including the pop-cultural force Chris Ware, the “Fun Home” author Alison Bechdel and the uncategorizable, realm-jumping Neil Gaiman.

Clowes, 55, has covered a wide range of styles. He began more pulpily, appropriating classic genre tales and art in his influential 1993 work “Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron.” He then evolved with works like “Wilson and Mister Wonderful” paying homage to early newspaper comics and taking on themes like aging. (Much of his work first appeared in the “Eightball” comic series, the glorious hodgepodge he put out for a quarter-century.) He also has worked in Hollywood, penning screen adaptations of his misfits-coming-together tale “Ghost World” and Pratt satire “Art School Confidential.”

In the faddish world of graphic novels he has managed to stay relevant across generations, transcending the ‘90s alt-comics scene from which he sprang to gain popularity with the film version of “Ghost World,” out in 2001 and starring a young Scarlett Johansson, and recently with “Patience” and “Wilson.”

He even got to be known among the millennial social-media set when Shia LaBeouf a few years ago cribbed a whole bunch of his work and then mock-apologized by having a skywriter scrawl the message “I Am Sorry Daniel Clowes” over Los Angeles.

“Wilson” is not an easy book to adapt. Partly it’s a function of style, or styles, since pretty much every page in “Wilson” is done up as an homage to a different comics form. But it’s also a more subtle, characterological challenge. Wilson is a tone-deaf truth teller of the most curmudgeonly sort, Larry David without the shield of success. On the page that can be charming; at 20 feet of cinematic relief it can be punch-worthy.

“I was surprised when the book came out how may people under 30 really love Wilson and all these older Wilsonian types hated him,” said Clowes. “A friend has a theory: ‘The closer you are to Wilson the more you dislike him.’”

Clowes’ work is full of misanthropes and snark, and historically the criticism has been that it’s too easy to do jaded. But that’s also because of how effortless — and stylish — he makes it look. In any event, in person he is none of those traits.

“He’s not really a scathing person, just a very nice guy,” Harrelson said. “He’s the kind of person who may not say something for a while, but then when he does it’s deadly funny.”

Clowes has made his name on his talent for fierce observation, and his characters are often both watchers of humanity and studies of idiosyncratically human behavior.

“He’s the kind of person who’s just fascinated by humanity — he’ll walk by people in an airport, people we’d never give a second look to, and he’s cataloging them so he can make them the centerpiece of his story,” Johnson said of the writer. Added Harrelson, “He’s got a deep understanding of the people in society you might overlook.”

Perhaps that’s why he doesn’t appreciate it much when the fishbowl glass is inverted. Clowes says he doesn’t much like giving public readings--“I prefer one-on-one. You can see when you’re at a reading and they’re disappointed you’re not speaking. They expect you to have a grand thesis, and I don’t really have a grand thesis.”

He says for all his screenwriting work he has little desire to make a modern animated movie. “I would if I could just magically project onto a cel and make images appear and not put in an insane amount of labor. But it doesn’t work that way. It would also have look like a hand-drawn cartoon from 1958. Today’s animated movies seem inhuman—half the charm of an animated movie as a kid was knowing someone drew it.”

Clowes made his way up to the top floor of the Strand, an antiquarian-books section and parlor-like respite from the swarming crowds down below.

“I have a little bit of a collection problem,” the author said, flipping through books like a signed Joseph Mitchell (”Look at how nice and neat that signature is”) and vintage French pulp (”There was all sorts of dreck on newsstands”). His eyes alighted on an obscure 1970s children’s book titled “The Adventures of Fathead, Smallhead, and Squarehead.” “See, that’s the kind of thing I’ll be passing and feel like I have to have. And then I’ll look at it on my shelf and say, ‘Why do I have that?’”

He squinted skeptically when he came across George Saunders’ acclaimed debut novel “Lincoln in the Bardo.” “I haven’t read it yet,” he said. “I think it’s because everyone else is reading it. You don’t want to be the guy on the train or the BART reading that book that everybody’s reading.”

He continued on the subject of Bay Area literary scene. “There’s this hippy bookstore I go to sometimes. I walked in once with Michael Chabon, and he stepped away to use the bathroom. I said to the owner, ‘You know, you have a Pulitzer Prize-winner in here.’ And the guy looked at me and said, ‘I stopped caring about the Pulitzer after Sinclair Lewis.’

“Some people,” Clowes added with a shrug, “just don’t want to keep up.”

Satisfied with his used-book perusing, Clowes stepped out on to the street to a waiting car, ready to whisk him to a broadcast interview. Asked if he indeed had been registering people in the store, or this reporter, the entire time, he replied, “My wife says it’s a problem. We’ll be in a restaurant talking and she’ll say ‘OK, turn your head back, look at me.’ But I can’t really do that in New York. You can get overload trying to catalogue it all.” Then he got in the car, sized up the driver and was off to his interview.

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour »

Twitter: @ZeitchikLAT

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.