At the Military Film Festival, veterans are the target audience

- Share via

Master Sgt. Juan Valdez was the last Marine to climb off the roof at the U.S. Embassy and into a helicopter that skirted the horizon as North Vietnamese fighters surged toward Saigon. The images from that day in 1975 were visceral and cinematic, marking America’s defeat and the unsettled legacy of the Vietnam veteran.

Documentaries and feature films have since given perspective to that war and its soldiers. But it is hard, said Valdez, who traveled to the Mojave Desert last week to speak at the first ever 29 Palms Military Film Festival, to authentically capture the scents, visions and surreal moments that grind through bloodshed and battle.

“The one movie that got really close to the Vietnam war was ‘Platoon,’” Valdez said of Oliver Stone’s brutal homage to the infantryman. “‘Apocalypse Now’ was OK but they threw some ... in there for humor. And what’s that Italian guy’s name?” He paused and lifted a hand to his white mustache. “Robert De Niro in ‘Deer Hunter’ was good. I read a lot about it. Vietnam is the war that won’t go away. Even 41 years later I’m still getting calls to talk about it.”

Hollywood through the decades has cast the American soldier as an Everyman turned into hero, troubled soul, glory seeker, alcoholic and existentialist. Both on the battlefield and back home, soldiers embody our anxieties, fears and justifications; they are the front lines of shifting politics and changing times.

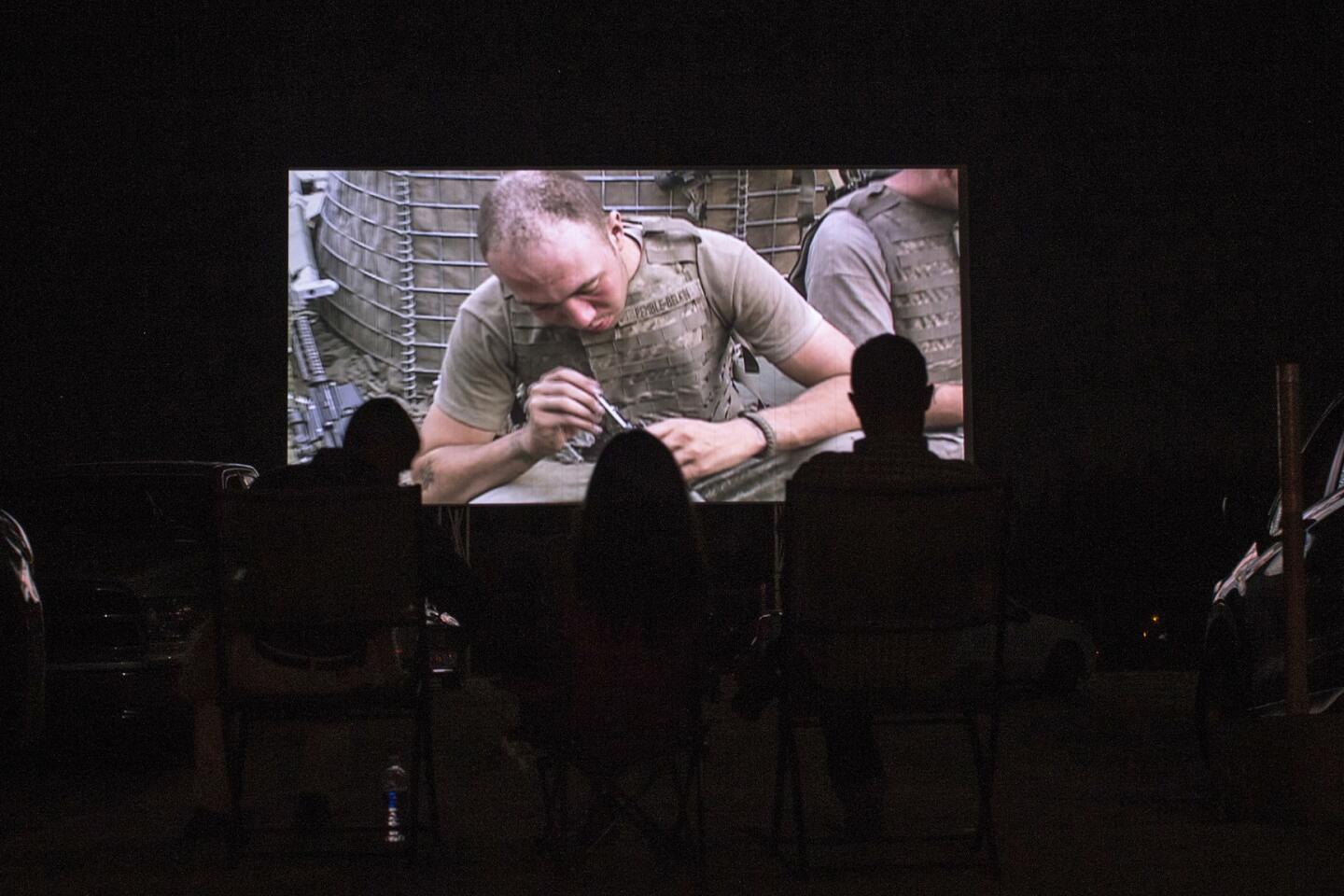

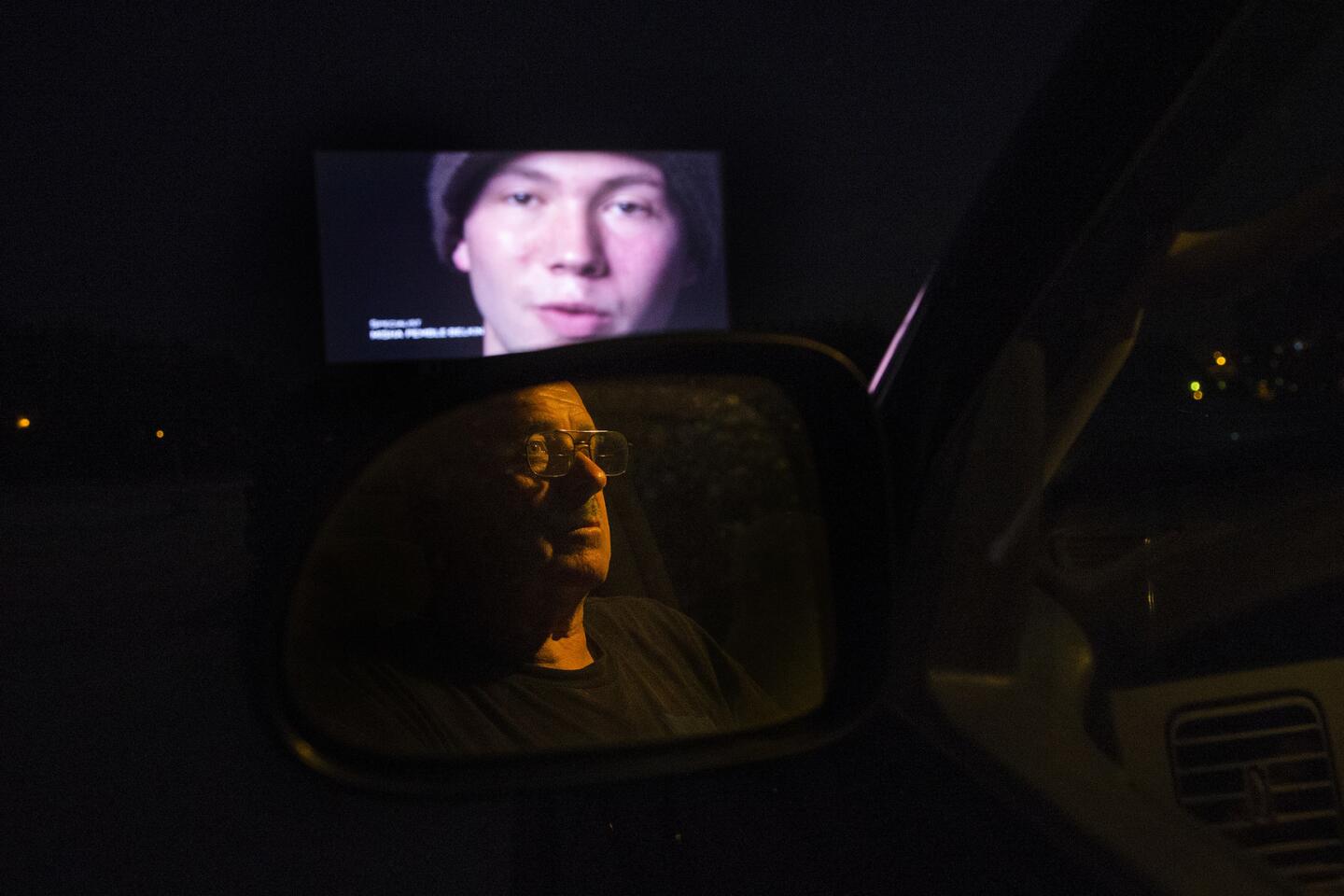

To understand the moral and strategic complexities – not to mention the failures – of military ventures one need only fast-forward from Saigon to Baghdad: U.S. forces withdrew from Iraq in 2011 but the rise of Islamic State prompted President Obama to reverse course and send back more than 4,000 troops. The films at the festival, some of which played under the stars at Smith’s Ranch Drive-In, evoked the isolation and the wonder mixed with horror soldiers encounter in distant lands.

That sense of wanderlust and adventure shaped Chase Millsap’s childhood. He grew up watching John Wayne in “The Green Berets” and was inspired to enroll in the U.S. Naval Academy by films such as “Top Gun” and “The Hunt for Red October.” After graduating from the academy in 2005, he went into the Marine Corps and served three tours in Iraq. He made a short film – “The Captain’s Story” – about an Iraqi officer he befriended who is now a refugee in Turkey.

“The idea that the war doesn’t leave you, that’s what the filmmakers of Vietnam-era movies got right. I thought ‘Deer Hunter,’ ‘Platoon’ and ‘Rambo’ did a decent job of showing the social repercussions of war,” he said, adding that today’s directors should focus on post-traumatic stress but also “that middle story of the day-to-day realities of coming back home to your community. I’d love to see a sitcom like ‘MASH’ come out and speak to today’s soldier. It doesn’t all have to be drama. There can be comedy.”

Twentynine Palms was a resonant setting for such discussions and for a festival program that included “Full Metal Jacket,” “Black Hawk Down” and “Flags of Our Fathers.” Home to the Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center, which gleams in the Morongo Basin, the city is a glimpse of tattoo parlors, fast-food restaurants, pick-up trucks, young brides, cases of Budweiser and signs advertising “military haircuts $9.” Marines trained here have done tours in Iraq and Afghanistan, and older residents reminisce about arriving decades ago as children in tow of their father’s latest orders.

Frank Sinatra’s voice drifted through the palms at the festival’s cocktail party. Vets from World War II, Vietnam, Iraq and other conflicts sipped wine amid canes, knee braces and stories of guns fired and ancient deeds done. Valdez recalled putting blown-up men into body bags and how “all those images come back.” The men mentioned war films they considered close to accurate and others they criticized for jingoism and caricature.

The older veterans came from generations that included the draft and produced filmmakers such as Samuel Fuller, whose World War II drama “The Big Red One” played at the festival, who had seen war. Many of today’s directors, although skilled in technology and craft, never served in combat and their films at times sacrifice understatement for hyper-reality.

Audience turnout at the festival was sparse, just shy of 500 admissions for 24 films. Festival co-director Patrick Zuchowicki said, “We had less active military personnel from the base than veterans and retired military personnel.” Among the most popular screenings were two Russian films: “Battalion,” set during World War I, and “Battle for Sevastopol,” the story of a female sniper in World War II.

Zuchowicki said the intent of the festival, one of the few in the country dedicated to combat movies, was to “honor the courage” that has long intrigued filmmakers. The festival urged veterans to share their war stories -- and scripts -- with screenwriters and directors. Organizers said the mix of films, including classics like “Casablanca” and foreign and cult favorites such as “How I Won the War” starring John Lennon, were chosen to represent diverse interpretations of war. One of the festival panels was called “Revisiting Hollywood’s Relationship with Vietnam.”

Vietnam was a turning point in how the soldier was depicted in both film and national consciousness. The flawed characters in Vietnam movies made in the 1970s and ‘80s were a prism of the psychological damage done to warrior and country. The home front’s recoiling at the war, which killed more than 58,000 U.S. soldiers, did not celebrate so much as abandon returning troops. That sentiment shifted dramatically during the American invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, leading to the glorification of soldiers in films such as “Lone Survivor” and “American Sniper.”

“The American soldier has been depicted unfairly in films,” said director Oden Roberts, whose feature “A Fighting Season,” an unvarnished look at military recruiters, was shown at the festival. “Not every soldier is quote-unquote a hero as we define him in film. They’re not John Rambo or Captain America. They’re ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances. To turn them into heroes ostracizes them in some ways.”

Kathryn Bigelow’s 2008 film “The Hurt Locker,” which won the best picture Academy Award, received praise and criticism from veterans. Some said the protagonist, bomb demolition expert William James (Jeremy Renner), was too full of swagger and recklessness to be believed. But Millsap said the scene in which James, just returned from Iraq, stands bewildered in a supermarket aisle captured the disorientation soldiers experience upon returning home.

“That was me to a T,” said Millsap, who was once stationed at Twentynine Palms.

Soldiers have been less reliant these days on Hollywood’s rendering of war. Multiple tours in Iraq and Afghanistan have turned them into auteurs. Phone cameras and social media have depicted unflinching battlefield realism and the boredom-breaking games and tediousness that fill the hours between patrols. This hand-held cinema verite has influenced feature films and documentaries, such as Sebastian Junger’s “Restrepo,” about a platoon of U.S. soldiers in Afghanistan.

“Films are getting more raw and realistic,” said Eric Hofmans, who served nine months with the Seabees in Afghanistan’s Helmand Province. “Soldiers with their iPhones can document war themselves. They’re capturing explosions and gunfire crack.”

He added: “You can really feel these guys in ‘Restrepo’ and you can see how ugly war is but you can also see the brotherhood that’s there. It used to be Hollywood reproductions like ‘Apocalypse Now’ or ‘Hamburger Hill.’ They were entertaining but not quite real. It’s getting more gritty.”

But it is the soldier and his unadorned story – whether ingrained in film or not – that carry the greatest power. Valdez, who appeared in Rory Kennedy’s documentary “Last Days in Vietnam,” speaks like a man you stumble upon at a car wash or a diner. He served 30 years in the Marines. He doesn’t make more of things than what they are – “I was involved in quite a bit of fighting” – and he doesn’t glance away from truths.

“We lost,” he said of America’s involvement in Vietnam. “We had to get out of there like a dog with its tail between its legs. . .The last 41 years I’ve been very bitter about what happened in Saigon.”

Twitter:@JeffreyLAT

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.