Still grieving, Anton Yelchin’s parents try to move forward with new documentary

- Share via

Anton Yelchin’s parents live where their son died. After his sudden death nearly three years ago, Viktor and Irina Yelchin couldn’t bear the thought of selling Anton’s home. He’d been obsessed with the place in Studio City, planting himself on his recliner sofa most nights with a bowl of pretzels, his Brussels Griffon, Elvis, and a stack of movies to watch until 3 in the morning.

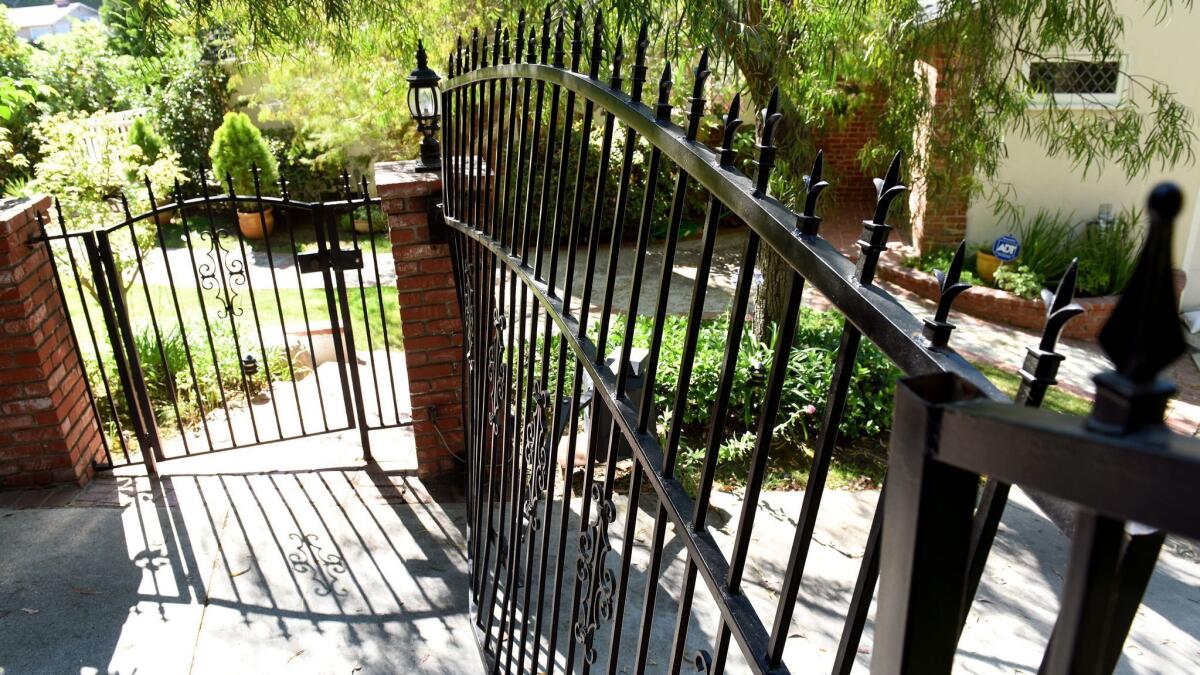

So even though it was in the driveway that his Jeep malfunctioned in 2016, rolling downhill and pinning him against a gate, this is where his parents felt they had to be.

“It’s difficult, but we feel his presence,” said Viktor, sitting on his son’s favorite leather sofa last week as the rain pattered on the roof. “We’re closer to him, even if it’s very hard.”

“It’s hard to walk there,” Irina said, her voice breaking as she motioned toward the driveway. “It’s hard to live. But we are. So we have to do something while we’re here.”

The couple have already done a number of things in tribute to their son, an actor who amassed close to 70 film and TV credits — ranging from the most recent “Star Trek” reboots to “Hearts in Atlantis” and “Curb Your Enthusiasm” — before his death at the age of 27. They erected a statue in his likeness at Hollywood Forever cemetery and donated $1 million to the newly named Anton Yelchin Cystic Fibrosis Clinic at Keck Hospital of USC, where he received treatment for the disease.

But at the Sundance Film Festival this month, they’ll debut their greatest labor of love: “Love, Antosha,” a documentary that celebrates the actor’s legacy.

The film, which debuts in Park City on Monday, Jan. 28, features revealing interviews with some of Anton’s many Hollywood collaborators: Kristen Stewart, J.J Abrams, Chris Pine, Jennifer Lawrence, Jodie Foster, John Cho, Martin Landau.

The documentary was the brainchild of one of the actor’s co-stars: Jon Voight, with whom he appeared in 2015’s “Court of Conscience.” After his death, Anton’s parents were sharing their grief with Voight, telling him how “we don’t see any reason to live anymore, that our whole life is over,” Viktor recalled. “He said, ‘Why? You have to live. Make a documentary and keep his memory alive.’

FULL COVERAGE: Sundance Film Fesival 2019 »

“Maybe it was a selfish reason, because Anton, we just didn’t want to let him go,” said Irina, surrounded by the dozens of photos and movie posters of her son she put on the wall. “He was gone, but everyone talked about him, and his movies were coming out still.” (Two of Yelchin’s final films, “Rememory” and “Thoroughbreds,” actually premiered at the 2017 Sundance Film Festival following his death.)

“Everyone was saying how brilliant and talented and smart and kind and tenderhearted he was. Maybe because of that. Maybe because he never left, truly.”

At Voight’s suggestion, the couple began pursuing the film idea more seriously, reaching out to Abrams for advice. The filmmaker suggested that someone who actually knew Anton should work on the project, so immediately Viktor and Irina thought of Drake Doremus, the director behind “Like Crazy” — one of Anton’s most beloved projects (and a Sundance grand jury prize winner in 2011).

Doremus felt he was too close to Anton to make the movie — they’d developed a close friendship after shooting the indie love story. So he enlisted his American Film Institute buddy, Garret Price — who’d never met Anton — to helm the project.

“It was so important the filmmaker didn’t know Anton and was objective,” explained Doremus. “It’s not like this is a perfect human being. There is so much darkness and truth in this, and that’s what Anton would have loved. He would have loved that it’s the truth, as opposed to a perfectly glossed-over version of a 27-year-old life.”

Perhaps the biggest revelation in the film is just how much Anton struggled with cystic fibrosis — a diagnosis he hid from the public and the entertainment business. As a precocious kid, he was pink-cheeked and enthusiastic, shooting short films with childhood friends and constantly performing impressions for his parents. He never seemed sick and barely demonstrated any signs of someone with the progressive disease, which causes mucus to form in the lungs.

In fact, he appeared so healthy that his parents decided not to tell him the full details of his diagnosis — CF patients have a life expectancy of around 37 — until he was 17.

“I didn’t want to introduce him exactly to what it was, because he was so artistic and so sensitive,” said Irina. “I was just afraid that he would go into it and he would get panicked or get affected by it too much. He didn’t even know what it was for real, how difficult and dangerous that illness was. Only after 17, 18, that’s when we talked, because I said: ‘You can’t go to this club. They are smoking there.’ You feel good, but it doesn’t mean you cannot get worse.’”

Upon learning about his illness, Anton worked hard to stay healthy, constantly running up and down the stairs and researching herbal remedies to try on top of his prescribed medications. Before long days on set, he’d wake up two hours early to put on an inflatable vest that helped him to clear his airways.

“I spent nine years with him, and I never knew,” said Doremus. “He always had a cough, but I just chalked it up to him just being sick all the time. We had to edit around his cough in ‘Like Crazy’ — we were like, ‘He’s constantly coughing, what’s going on with this guy?’ We didn’t know. Some of his really good friends didn’t know.”

Prior to his death, Anton had booked the show “Mr. Mercedes,” and he told his parents he was ready to publicly share his illness on the press tour. That’s the only reason why they said they decided to reveal his diagnosis in the documentary, which they hope inspires others with illness to live life to the fullest.

The film shows how eager Anton was to dive into artistic pursuits, spending hours marking up scripts, venturing downtown to shoot photography at seedy dive bars and performing in his own band. He cultivated a close group of friends and admirers, including Stewart, who admits in the movie that Anton “kind of, like, broke my heart” at age 14 after they appeared together in “Fierce People.”

“We had talked about that over the years, but I never in a million years thought she would be comfortable with sharing that,” said Doremus. “But it’s so important that she did, because it really reflects on Anton’s relationship with women and understanding his relationship with his mom.”

Indeed, Anton, an only child, was exceptionally close with both of his parents. When Irina got pregnant, the couple — well-known pair figure skaters in their native Soviet Union — decided to move to America. They arrived here when Anton was barely 6 months old and settled in the San Fernando Valley. He wasn’t afraid to show his parents affection, and constantly wrote them notes declaring his love for them. One such letter is framed in Viktor and Irina’s home now:

“My dearest parents, I love both of you so much! You guys are the best. When I act like a jerk and am selfish, I feel like killing myself. I think that all 1000s of kids on Earth would be jealous of me because of you … Happy New Year! Love, Anton”

As Anton grew older, eventually moving out and into his own place at 22, they sold their house in Tarzana and moved into a townhome just a few blocks away. Irina and Anton spoke on the phone every day, and most nights he’d have dinner with his parents.

Now, they visit his grave every day. Each Saturday, they let a heart balloon fly off into the sky in the hopes he’ll receive their love. Irina has planted heart-shaped gardens of flowers in the front yard, near where the accident occurred, and still drives the Porsche her son gifted her.

Asked if working on the documentary was therapeutic, Irina shook her head.

“It’s not such a therapy,” she said, tears clouding her glasses. “It’s just not. It doesn’t exist. Poor Viktor, because we needed to go through the home videos. I would ask him to close the door and he would go and watch every single video to give it to the film. Was it therapeutic for you?”

“It’s a strange feeling,” said Viktor, petting their three Brussels Griffons, one of whom was Anton’s. “It’s very hard, for one, and I’m happy to see him alive, on the other hand.”

Joy is still hard to come by for Viktor and Irina. When Anton died, they quit their jobs coaching figure skating because it was too difficult to be around loud music, putting on a happy face. Irina won’t go shopping at the mall anymore because it’s too chaotic, and she only listens to the news while she’s driving.

“Nothing is fun anymore,” Irina said, though she tries to take pleasure from what she sees as signs from Anton: Clouds shaped like hearts in the sky, tulip stems that sprout extra buds.

“We’re trying and trying. I’m trying to put on makeup in the morning, because Anton would always say, ‘You look so cute.’ I do it, and by the night, it doesn’t matter, it’s disappeared.”

Still, Price said that through the process of making the documentary, he’s noticed Viktor and Irina smiling more every day. He said he’s hopeful the movie will bring them a bit of solace.

“They’re so broken. And it’s completely understood why they are: Anton was their life,” said Price. “All they want to do is to talk about Anton, and now they have this tool. I hope that they can continue to do that in a different way than just telling stories. They can show something.”

“When people come up to them at Sundance and want to talk about Anton and ask questions,” added Doremus, “I think that is the point right now. That is where their joy can come from.”

Irina said feels like she and Viktor have done right by their son with “Love, Antosha,” sharing his spirit with the world.

“With this movie, it was difficult because everyone knows the end,” she said. “It can’t be changed, and you can’t avoid it. But I think people will love it, because even though everyone knows the end, they’re still smiling and laughing. We had the best baby in the world.”

Follow me on Twitter @AmyKinLA

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.