The Sunday Conversation: Violence in entertainment has long history, film expert says

- Share via

Elizabeth Daley, a former producer, has served as dean of USC’s School of Cinematic Arts for more than 20 years. She’s also the founder and executive director of the USC Institute for Multimedia Literacy, which develops educational programs and conducts research on “the changing nature of literacy in a networked culture.”

What purpose do you think violence serves in entertainment?

It’s so interesting as to how you define what we mean by violence in entertainment. Should we talk about Oedipus? Should we talk about Hamlet? Should we talk about any of the great [works of] theater or literature? Many of the stories we tell are about conflict. So I can’t think of a period of entertainment that’s been violence-free.

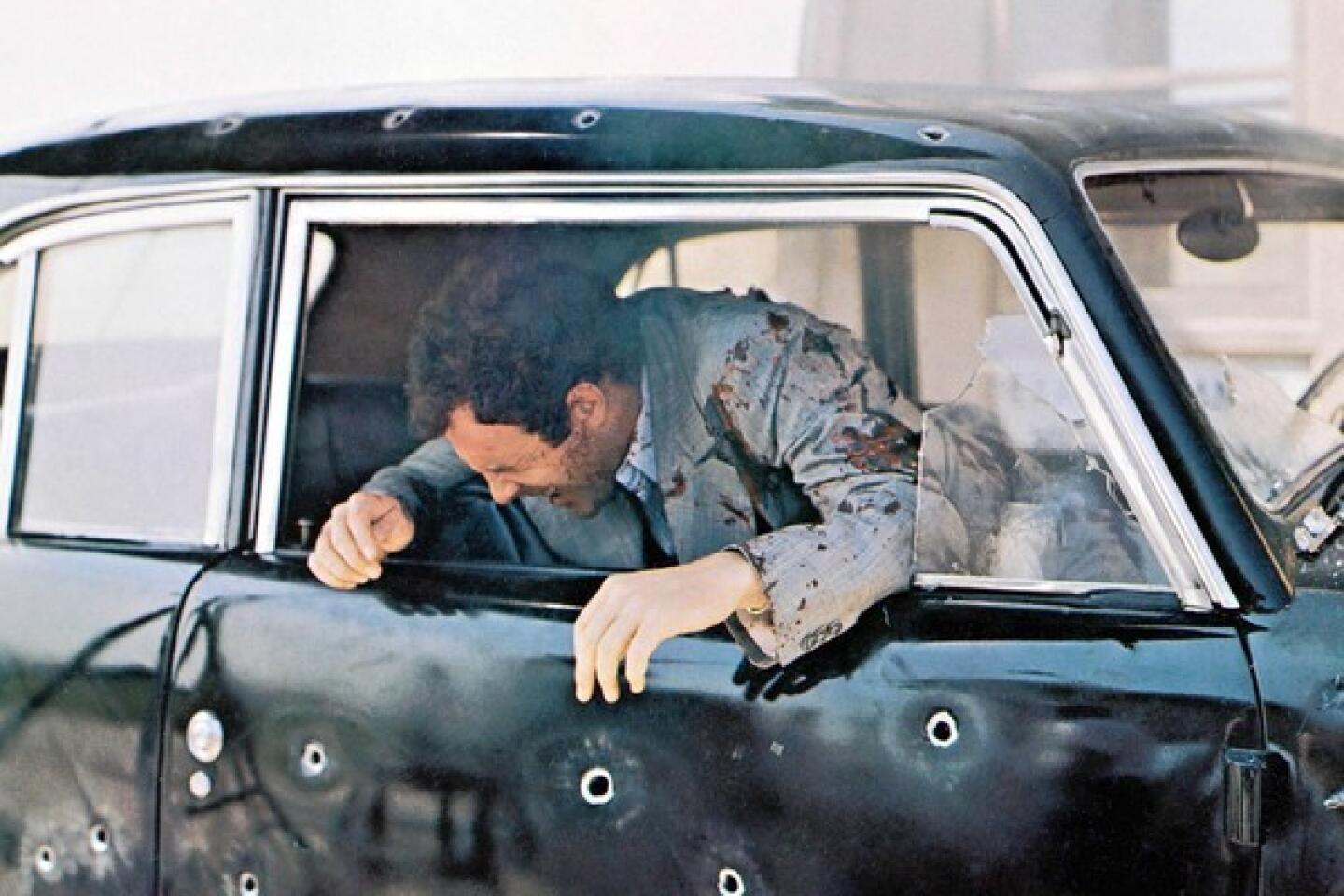

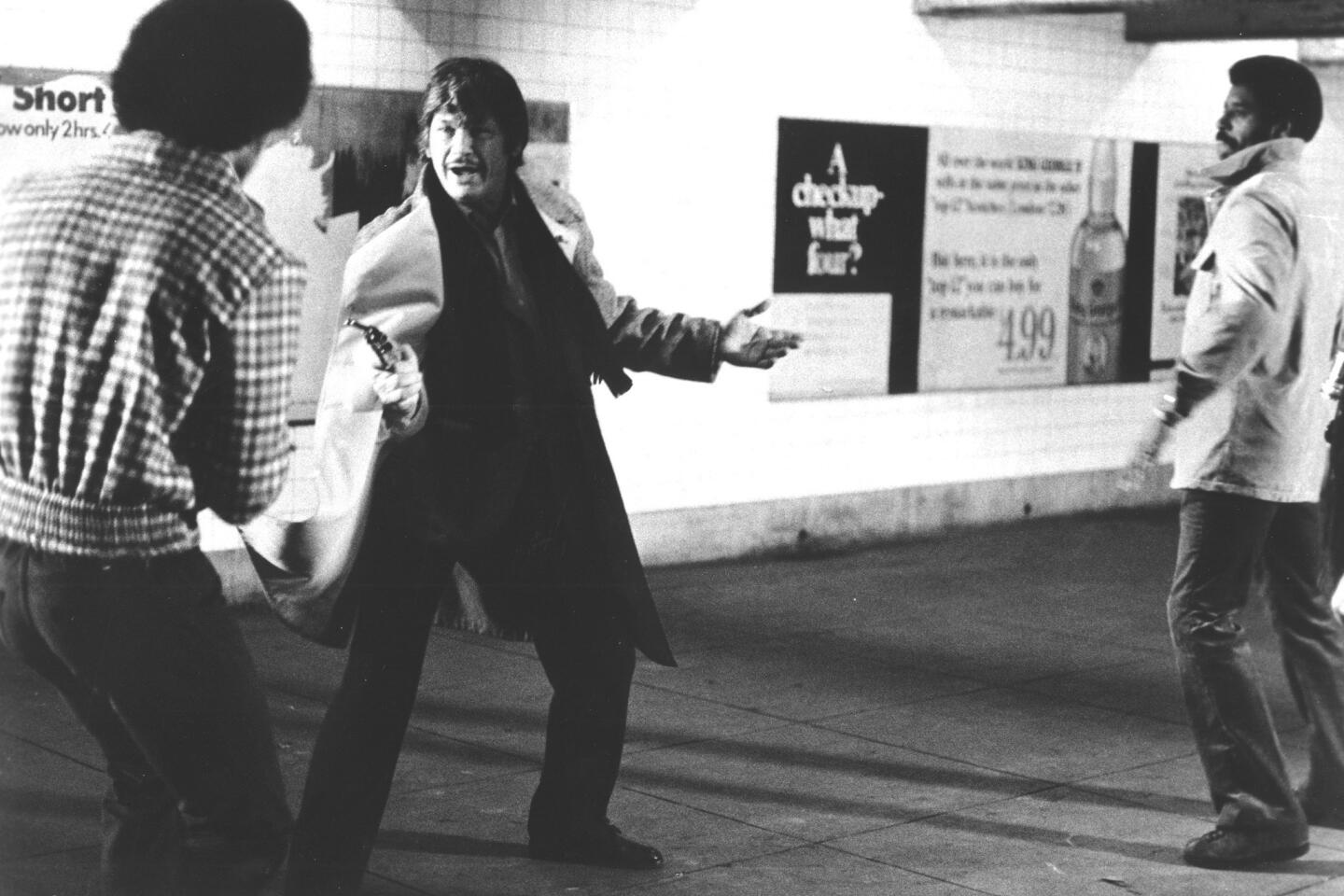

THE CULTURE OF VIOLENCE: Art | Film | Television | Hollywood

And yet it’s been growing more graphic in recent years. Why do you think that is?

I’m not even sure it has been. Is entertainment more horrifying than what we see on the nightly news? I think our society, certainly we are more aware of violence in it, although the rate of violence among teenagers has actually been dropping.

What does that tell you then? That there’s no connection?

I think the studies that have been done are very inconclusive. [reading] “The Pew Internet in American Life project in 2008 found that 81% of Americans between the ages of 19 and 29 play [video] games.” We don’t have 81% of our people running around murdering people.

Do you think someone would have to be mentally deranged to imitate in real life what he sees on the screen?

I would think so.

Do you think the industry has any responsibility to shield the mentally ill?

How can you? Who knows who’s mentally ill? The tragedy is we don’t have support for the mentally ill.

THE CULTURE OF VIOLENCE: Video Games | World Cinema

Do you think the industry is ducking the issue or do you think the media are being used as a scapegoat for gun violence?

Look, we’re a cheap target, right? Let’s just look at recent events — we were saying 81% of [young] Americans play games. We certainly know that many watch TV and go to movies. Let’s just take Canada, the country that’s probably closest to us in terms of culture. They watch exactly the same media. The murder rate in Canada is minuscule compared to ours. At the same time, ours has been dropping.

But I think we need to address what are clearly the real problems, which in my opinion are guns. Why anybody needs an assault rifle is beyond me. We also need to address better healthcare for the mentally ill. I think we would all be very happy to see serious studies done. But sitting around counting the acts of violence [on-screen], I mean, you can count the acts of violence in Aeschylus.

Is it possible to say that a movie or video game crosses the line to being too violent, and what would constitute that?

I never go down that road. What we do say to our students is, you’re responsible for what you put on the screen. So if you put up things, whether it’s violence or language or sex or whatever that’s gratuitous, then you have to say that that’s who you are. But if you can honestly say you think it’s necessary to the story you’re telling, then I would be very hesitant to ever draw that line. We live in a country with a 1st Amendment, and to me that is more important than drawing any line about too much.

But certainly you’re going to draw the line at things like child pornography, my goodness yes. None of us has a problem with drawing that line and saying it’s a criminal act. But when you start to say, is “Django [Unchained]” too violent? Frankly, I thought “Django” was one of the most impactful condemnations of slavery I’ve ever seen. And it was very violent. But so was what was being done to people.

So you think the filmmaker’s responsibility is not to have gratuitous violence?

I think the filmmaker’s responsibility is authenticity. It’s being willing to put yourself on the line for whatever you make. We’ve obviously tried to rate things; I think that’s important, so that parents do have some guidelines. On the other hand, we never seem to rate for violence. We only rate for sex and language.

Nina Tassler, who produced “Criminal Minds,” basically said she wouldn’t let her children watch the show. It wasn’t for them; it was for her. So I do think there is a certain kind of parenting responsibility here.

What I’m most worried about right now is we clearly need to do a lot of things in our society, and if we’re just going to say, “Oh, well, the media caused it,” there’s no proof of that whatsoever. We don’t have the research done, but at the moment what we do know is that we don’t have good healthcare for the mentally ill. I want us to quit ducking the real social issues of poverty and lack of healthcare and failure to regulate guns. I’m frankly really perturbed that we would try to dismiss the horrors of Colorado or Newtown or Virginia Tech and say, oh, it’s video games.

THE CULTURE OF VIOLENCE: On-screen history | Theater | Research

So you don’t think the industry should be self-censoring?

In many ways, that’s what the ratings system is. We always have been, in many ways, self-censoring.

There are all sorts of regulations about how you deal with minors in films and animals in films. And I think, knowing many of the studio heads, these are not people who are anxious to create things that they think are harmful to society. They’re mostly very responsible citizens. These are conversations we have every day with our students. What’s the impact of the film? What’s it saying? Not just violence, it’s what does it say about women? About race? About social class? What does it say about the way we deal in a global society? I don’t know filmmakers that don’t ask these questions.

What about gratuitous violence on-screen? Is that the price we pay for freedom of expression?

You probably do pay that price. And who’s going to define what’s gratuitous? This is when I get worried. Now there are films — and I’m not going to name any — that I won’t go watch, because I don’t want to see them. I don’t want those images in my head. But that’s my choice. It’s not anybody else’s choice.

And I would always err on the side of respecting the 1st Amendment. What we try to do with our students is we say, “All right, we won’t censor you. You have no right to do things that damage other people in your classes, but you’re going to have to justify what you do.” You want to get into trouble around here, real trouble real fast? You say, “Well, it’s only entertainment.” You probably will get asked to leave the school. Because we consider entertainment to be important. What you put on the screen matters, but you’ve got to decide that, and you’ve got to take responsibility for it.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.