From the archives:: Q&A with David Bowie: The man who fell ... then got up again

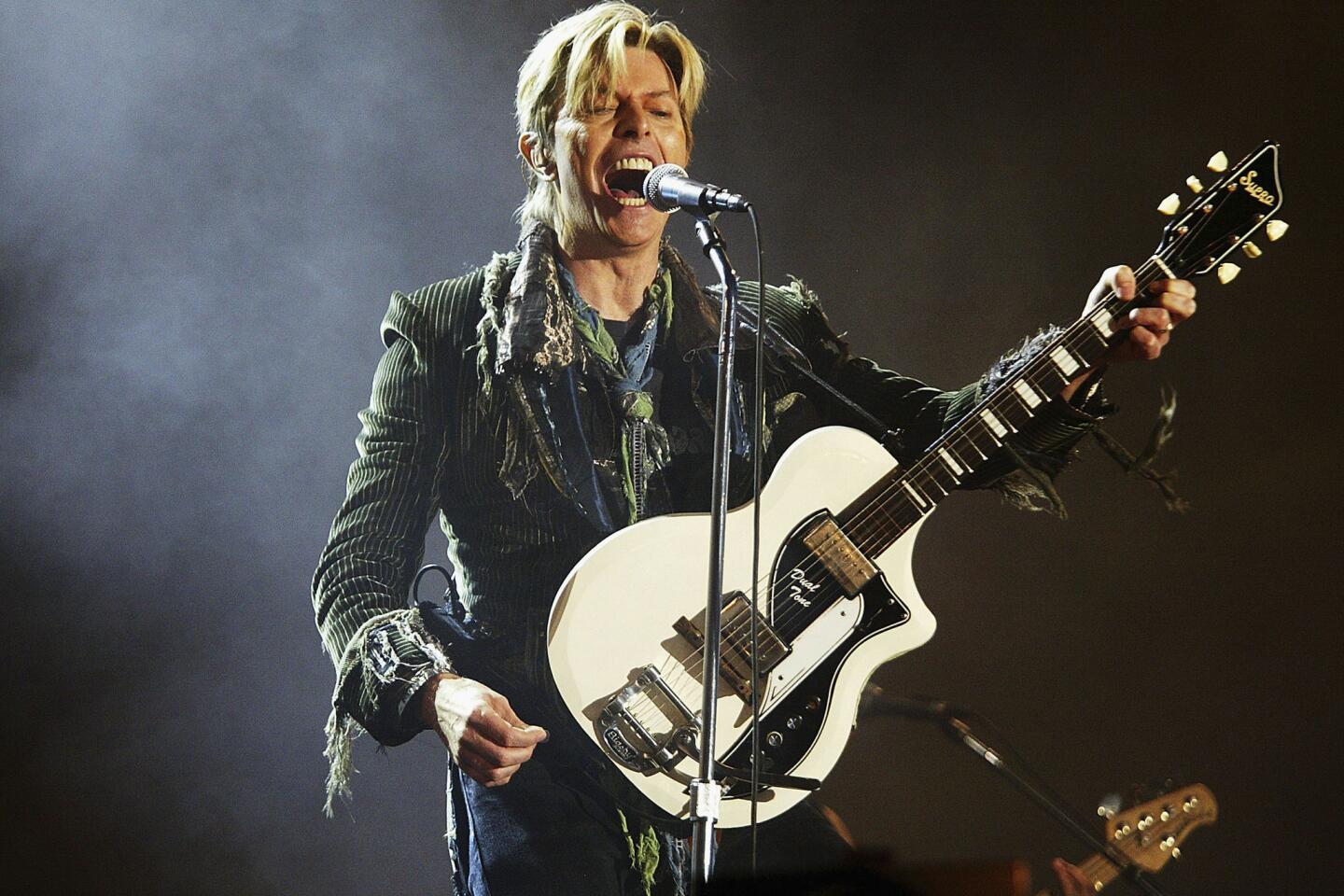

David Bowie performs at the Olympia concert hall in Paris on Oct. 29, 1991.

- Share via

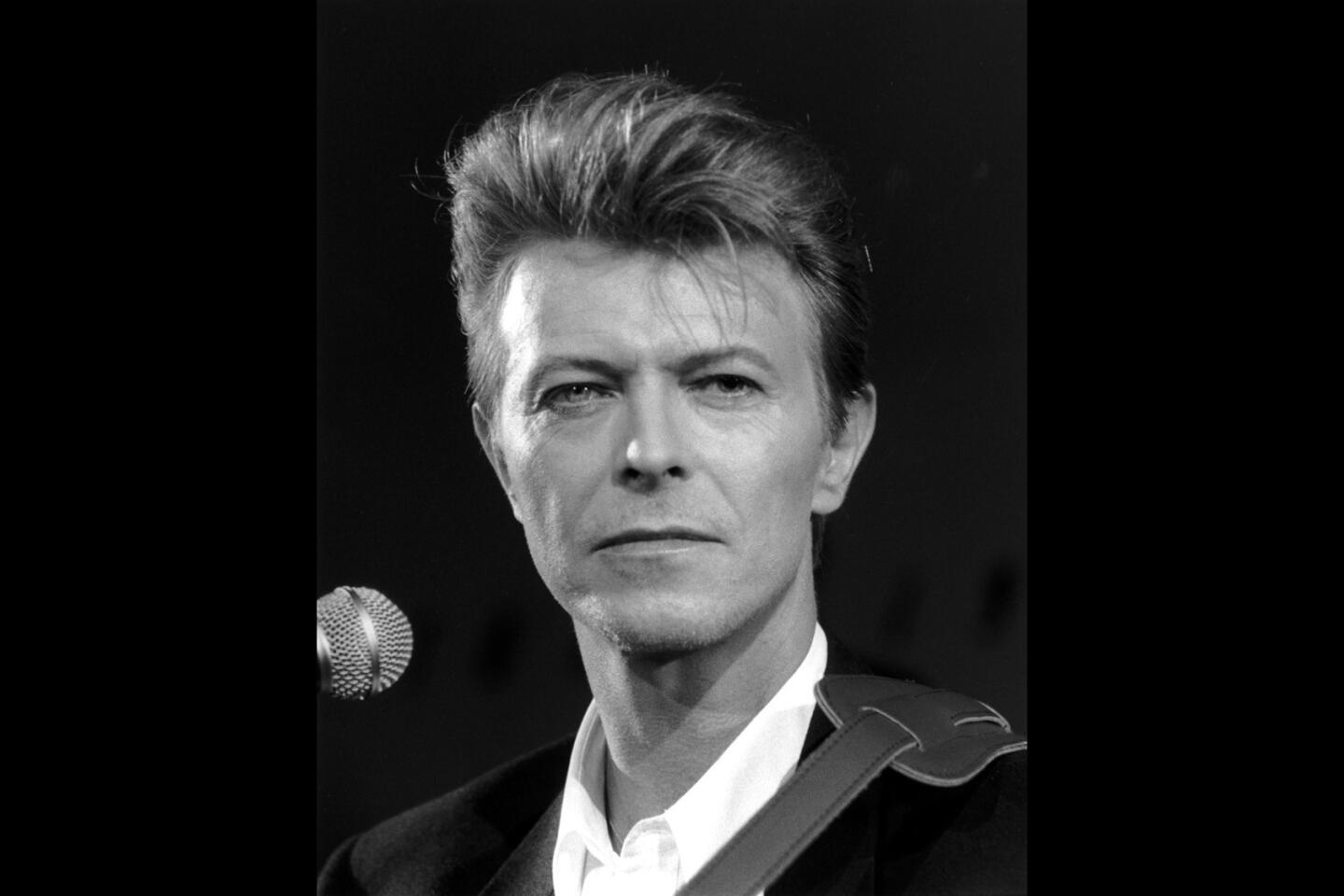

David Bowie died Sunday at the age of 69. The following is from a 1993 interview.

Icy. Cynical. Self-absorbed.

Those were just a few of the darker images adopted and mastered by David Bowie in the ‘70s, when he reintroduced the terms boldness and risk to a stagnant rock world through such landmark albums as “The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars” and “Low.”

By the end of that decade, the constantly shifting images had become so intertwined with his personal life that it was hard to distinguish between his art and his demons, including drugs.

But a new set of attitudes dominates Bowie’s conversation these days: Love. Marriage. Sobriety.

In many ways, it adds up to the most remarkable change of all by the man who didn’t just create a parade of mostly neurotic characters for his albums and stage shows, but frequently changed musical style--rock to cabaret to soul--as well as career direction as he ventured into movie and stage acting.

The Englishman was a dominant figure in ‘70s rock, but he didn’t become a mega-seller until 1983, when “Let’s Dance,” a funky single produced by Nile Rodgers, opened the way to platinum albums and stadium tours.

It wasn’t a comforting experience for Bowie, who now admits that he tried in “Tonight,” the widely panned follow-up to the “Let’s Dance” album, to duplicate that hit-making recipe. His 1987 “Never Let Me Down” was also considered a major disappointment.

Feeling the need for creative rejuvenation, Bowie took an unprecedented step in 1990. He vowed to never again perform his old songs in concert, thus betting his future on his ability to write compelling new music.

After two albums with the band Tin Machine and his 1992 marriage to Somalian-born model-actress Iman, he found the confidence and desire to attempt his first solo album in six years. “Black Tie White Noise” is due Tuesday from Savage/BMG Records. (See review, Page 66.)

During a recent interview, Bowie, 46, seemed unusually relaxed as he sat in the warmth of the morning sunshine and spoke about the latest changes in his life.

Q: Even though you were married in the ‘70s (to Angela Bowie, who recently wrote a book about the couple’s life together), it seemed hard to think of you as the love and marriage type. Were you as cynical about it as you appeared?

A: I think I quite desperately wanted to have that kind of special companionship . . . a special relationship, yet I hid from it for many, many years and pretended to be cynical about it.

Q: Why?

A: I think the first experience scared the hell out of me. Within months of my initial marriage, I realized I had done a really naive and rather stupid thing. . . . I don’t think either of us had any real resolve about being together. The result was it made me wary of relationships.

As if that wasn’t enough of a (hurdle) to new relationships, my life started taking on all the problems of addiction. So that took me off into an area where relationships were absolutely impossible to handle on any real level. . . . Even communicating with other people was impossible.

It took me a long time to reach the bottom and it went through various stages. I went from drugs into an alcohol stage. For a while, one feels, “Ah, I’ve kicked drugs,” but what I discovered was I had another addiction instead.

Q: When did you reach bottom in terms of the personal problems?

A: By the mid-’80s, it was really apparent to me that I really needed to stop losing myself in my work and in my addictions. What happens is you just wake up one morning and feel absolutely dead. You can’t even drag your soul back into your body. You feel you have negated everything that is wonderful about life. When you have fallen that far, it feels like a miracle when you regain your love of life. That’s when you can begin really looking for a relationship . . . when you can (appreciate) the whole concept of giving to someone, not just taking.

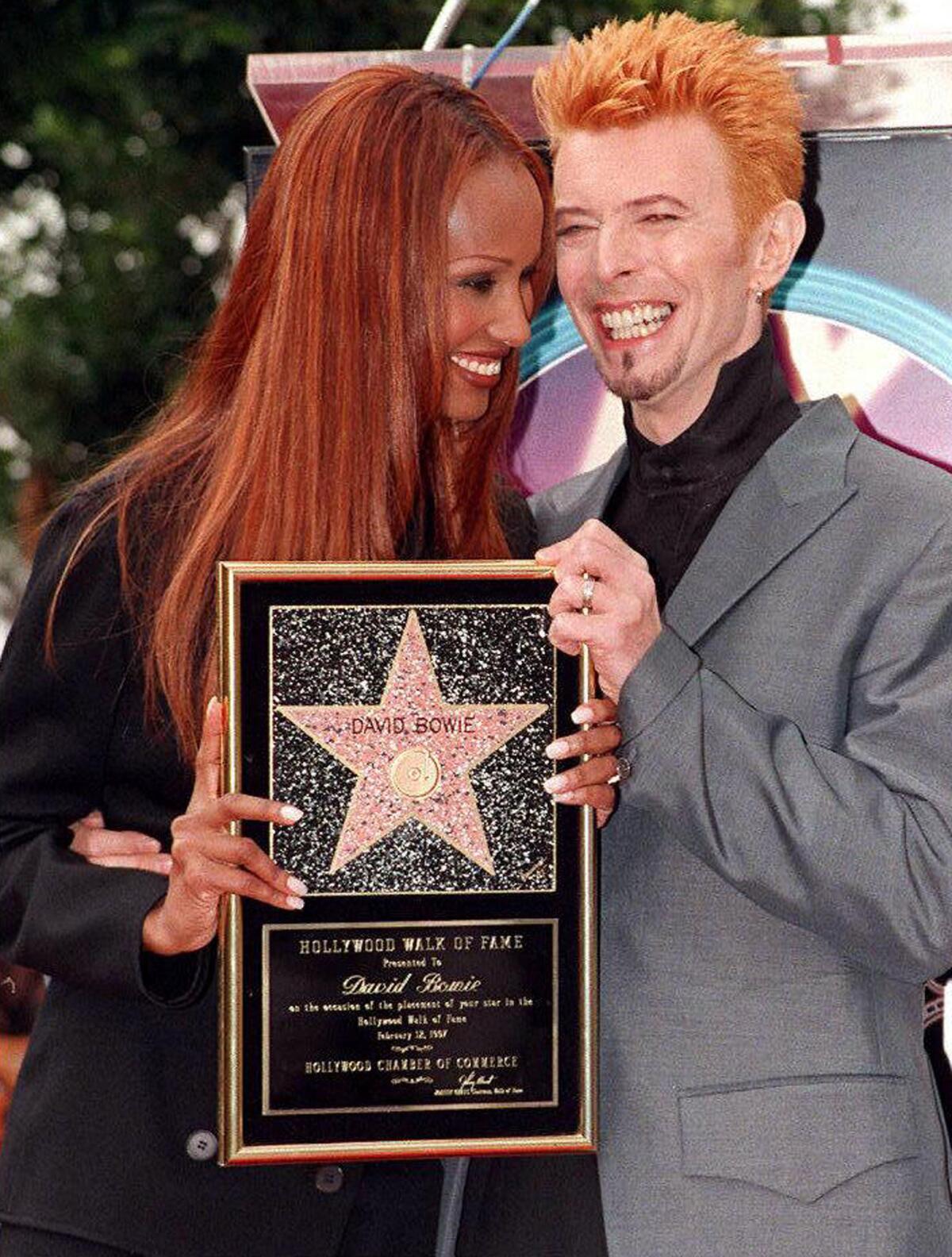

David Bowie and his wife, Iman, smile after Bowie received a star on the Walk of Fame in Hollywood on Feb. 12, 1997.

Q: How did you meet Iman?

A: A mutual friend knew that we were both on our own, with broken marriages and with children. We were brought to dinner one night. . . . It was absolutely instantaneous. I couldn’t get her out of my mind . . . sleepless nights--real 18-year-old stuff.

Q: How much time do you see each other now? Is there time for a personal life within your careers?

A: We see each other a lot. I couldn’t stand to be separated for months. It became quickly apparent to me that I needed to find a balance between my absolute work obsession and a private life that we could share without my disappearing all the time. With this album, I’m not touring at all. I think getting married and then running away for 10 months would be an absolute disaster.

Q: Did you write “The Wedding Song,” the opening track on the album, for the wedding?

A: When we decided to marry, we had two ceremonies--one was more bureaucratic for the sake of the Swiss authorities (Bowie’s primary residence is in Switzerland), then a church service in Florence, and I wrote the music for the church service. The challenge in that was that Iman’s family are Muslim and mine are Protestant. I had to be careful about the prayers that we chose and the music I wrote because I didn’t want to offend either side. That music ultimately became the focus for the new album--inasmuch as it opened me up to writing quite a lot about the last two or three years.

Q: The album’s title song is about the Los Angeles riots. Isn’t it unusual for you to be so topical in your music?

A: Iman and I arrived in Los Angeles from Italy on the day the Rodney King verdict was announced and the riots started, and it was a very numbing experience . . . a sense of true revolution. It did seem to have the feel of nothing less than some kind of prison riot. . . . People who had been treated inhumanly, not given a chance to secure any foot on any ladder--and all the social mores were suddenly abandoned.

When I finished the song, I gave it to (R&B singer) Al B. Sure! to read and fortunately he found it pertinent and agreed readily to do the song with me.

Q: Did you worry when you decided to work again with producer Nile Rodgers that people would think you were just going to make another “Let’s Dance”?

A: I think every time I said, “I’m working with Nile,” the reaction was, “Oh, great. I love ‘Let’s Dance.’ ” I think that’s pretty expected. I’m not sure Nile and I went in consciously not to make “Let’s Dance.” We just wanted to work together again. I felt it would be nice to sort of introduce melody into what I consider the new rhythm and blues, and he was thinking very much in a similar direction.

Q: What about “Tonight,” the follow-up album to “Let’s Dance”? Weren’t you guilty then of trying to copy a successful formula?

A: Yes. I was almost overnight Establishment. It was an extraordinary feeling. I was pressuring myself. I thought, “Well, I’d better adapt to the change that I had been put into.”

Q: But you had considerable success before, during the “Young Americans” period in the ‘70s, for instance--and you remained challenging. What was the difference?

A: You’ve got to remember that during “Young Americans,” I was so out of it. I really have trouble recalling that period with any real clarity . . . as to what my reaction was to anything at that particular time. That wasn’t the case after “Let’s Dance.” I was very clear-headed in a way, even though I made the wrong decision.

I had very deep concerns about my financial status because I found that up until “Let’s Dance” I was virtually broke again. I had been so irresponsible in how I dealt with my financial affairs. I take full responsibility for that. With “Let’s Dance,” there was actually a chance that I was actually going to be able to keep the money I had made.

On “Tonight” I think I was torn dreadfully between writing what I wanted to write, but keeping it in a style that would follow up what I had just done. That’s where I feel I was untrue to myself as an artist . . . that album and, to a lesser extent, “Never Let Me Down.” I think a lot of that album is still very good . . . the songs, but I think I was indifferent to the arrangements.

Q: You were clearly one of the most important figures in rock over the last two decades, yet the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame voters have passed you over three years now. One reason is some people thought you were never serious about rock. How do you feel about that?

A: I have complete sympathy with anyone who says, “Well, what exactly is he? He sort of does a bit of this and a bit of that.” There’s the suspicion that anyone who hops around like that doesn’t have a real sort of love for any of it very much.

Q: What was your burning vision when you started out?

A: When I was going through those very fast changes, I think it was terribly important to me that I was seen to be inventive. I think that was the characteristic of my work that I wanted people to see. It was fun to be clever.

Now, I think I am a lot more relaxed about what I have or haven’t done. I know its weight, I know its importance. I almost feel that I don’t really have to try very hard to prove anything anymore in that way. Over the 20 years, it is evident what I’ve done.

Q: Any second thoughts on the vow to not do the old songs anymore?

A: Not yet. I wouldn’t have a problem utilizing some of those songs for some agency or charity work. But I don’t see any room for them in my own concerts. I’ve interpreted and portrayed those songs until I’ve ground them into the dust. I really don’t need to dig them up again. I want to explore fresh ground.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.