Monkees’ Michael Nesmith spins ‘an autobiographical riff’ in ‘Infinite Tuesday’

- Share via

The signs were there pretty early on, had anyone been paying attention, that the young Texas kid who eventually would be dubbed “the smart Monkee” was, well, traveling to the beat of his own drummer.

“When I was 14, I applied for a job at the music store … and I was refused,” Michael Nesmith writes in “Infinite Tuesday,” a new reflection on his life suitably subtitled “An Autobiographical Riff.” “Obviously I was too young, but I just started working there anyway, on my own.

For the record:

12:55 p.m. Jan. 23, 2025An earlier version of this post described Nesmith’s 2009 novel “The America Gene” as an online download. It was published in physical and digital form.

“I came in one day, hung around, saw a broom leaning in a corner, grabbed it and started sweeping up and organizing the storeroom. There was just enough of a bureaucracy that no one knew whether I had been hired or who I worked for or what I was actually doing there. I came in the next day, and the next, and they all got used to me.”

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour »

That incident, which sounds like the blueprint for the classic “Seinfeld” episode in which Kramer reported every day to a job for which he’d never been hired, is fairly indicative of the way Nesmith has moved through life for 74 years.

In his memoir, which Random House will publish April 18, he writes of inventing his own high school schedule, attending those classes that interested him, skipping those that didn’t. “My self-designed school day consisted of three lunch periods, three choir periods, two speech and drama periods and a homeroom,” he writes.

The same free-spirited mind-set prompted him, at 20, to leave the Dallas home of ihis single mom — Bette, who would go on to invent Liquid Paper and amass a fortune — for the bright lights of Hollywood.

“I was in flight,” Nesmith explains now between bites of a chicken sandwich at a hole-in-the-wall restaurant across the street from the Burbank hotel where is he camped out during a quick trip to L.A. from his longtime home in Monterey.

“When you do that, you think, ‘I’ll head to a beach in Mexico — or Africa, or the South Pacific — and live off coconuts and whatever rum you can bargain.’ But those are fanciful. When you are really out there in full-scale flight, you think about the weather, and where you might know somebody and Hollywood is where it’s at.

“At least,” he adds, “at 20 years old that sounds like the truth, and you hope it is the truth.”

After several years as a starving artist — some of which he spent emceeing weekly hootenanny sessions at the Troubadour in West Hollywood — he was cast in “The Monkees,” a television show created and co-produced by Bert Schneider and Bob Rafelson in response to Beatlemania and the success of “A Hard Day’s Night” and “Help!” (Rafelson parlayed his “Monkees” success into a film career that included the 1970 counterculture classic “Five Easy Pieces.”)

But Nesmith was a maverick not a teen idol, emerging in the mid- to late-’60s as a pioneer of country-rock music and later as a visionary whose early blends of music and video earned him the first Grammy Award ever bestowed on a music video.

In 1974, that same innovative mind-set fueled the launch of his own Pacific Arts record company as an alternative to the major label system and most recently led to “Infinite Tuesday,” a lively and unconventional reflection on his life. He’s scheduled for an April 27 question-answer session with moderator D.A. Wallach as part of the “Live Talks L.A.” series at the Moss Theatre in Santa Monica.

The book’s title — for which he quickly credits his publisher — references a single-panel comic by Paul Crum first published in 1937 in the British magazine Punch, which appealed to his absurdist sense of humor: Two hippos stand side by side in a pond, nearly submerged, and one says to the other, “I keep thinking it’s Tuesday.”

“The cartoon was a window into a playground where other people thought as we did,” Nesmith writes in the first chapter of the book, which ping-pongs from decade to decade, subject to subject in a manner not unlike Bob Dylan’s autobiographical “Chronicles, Vol. 1.” “It showed me that someone else shared my sense of humor and my sense of absurdity.”

The book, Nesmith explains in the soft, slightly sandpaper-edged voice that’s been a signature of his vocals, is “anachronistic in a way, because I certainly didn’t plan on saying ‘And then I wrote, and then I did this, and then I learned, and then I found out…’ That was never part of it.

“What was a part of it, what I said in the preface, is [the approach of Federico Fellini’s 1973 film] ‘Amarcord.’ I’m looking back over these events that I can’t quite remember, so I fill in the gaps, like we all do,” he says. “It’s not a lack of memory, it’s just the way we all go into our past. And putting that together in the context of a life lived.”

Not surprisingly, the book reads like the chronicle of a relentless seeker rather than the diary of a celebrity, although Nesmith certainly doesn’t ignore the professional and social collaborations he’s had with “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy” author Douglas Adams, members of the Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, actor Jack Nicholson and numerous others.

In one chapter, he tells of heading off one evening in the 1960s to the Palomino country music tavern in North Hollywood just as the Monkees had become household names. He’d befriended Nicholson, yet to achieve stardom, through their mutual friend Peter Fonda, and invited him along to catch one of Nesmith’s heroes, Jerry Lee Lewis.

“At one point, Jerry Lee began to introduce me from the stage, having no idea who I was or what I looked like,” Nesmith writes. “He had been told only that ‘one of the Monkees’ was in the audience. Jerry Lee started the intro, looking directly at Jack, finally pointing at him with a flourish and saying to the crowd, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, one of the Monkees! Please stand up and take a bow.’ …Nicholson’s light was shining so bright even then, even when he was unknown, that Lewis pegged him for a standout.”

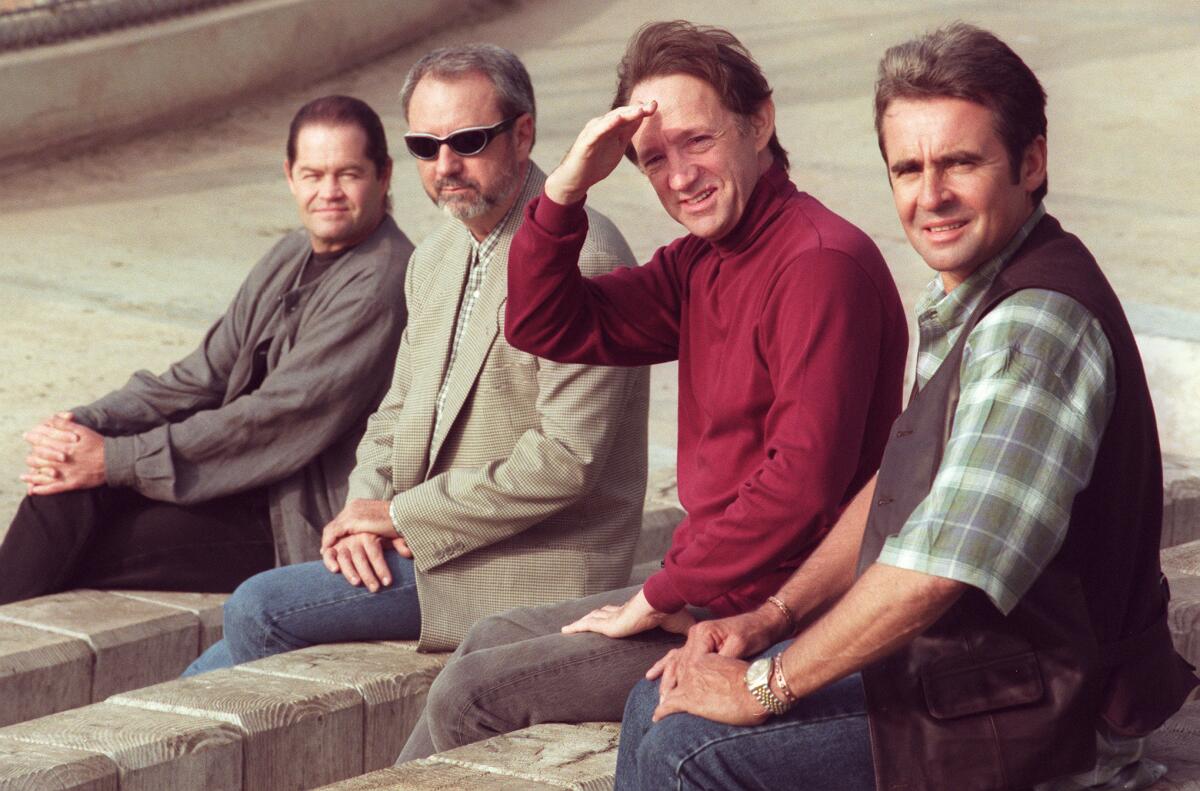

Just a single chapter of the book is devoted to his years with the Monkees, even though the TV show’s relatively brief two-season run made him a bona fide pop star and provided lifetime recognition for him and the guys with whom he once monkeyed around: Davy Jones, who died in 2012, Micky Dolenz and Peter Tork.

His experience in “The Monkees” brought fame beyond his wildest boyhood dreams but was accompanied by a plethora of challenges, one of which he shorthands in the book as “Celebrity Psychosis,” an affliction that causes the sufferer to inflate his own importance beyond all reason.

For years after that he distanced himself from the show, and his former band mates, but over time reached a sense of acceptance about what he’d been part of.

“To watch the internal dynamics of the Monkees persist — that is to say, what was good about it — was gratifying,” he says. “But it’s not the topic of the book.”

After joining Dolenz and Tork on a 50th anniversary Monkees tour last year, Nesmith indicated he’s hung up his wool knit Monkees cap for good, leaving Dolenz and Tork as a duo to keep serving up such effervescent pop hits as “Last Train to Clarksville,” “Pleasant Valley Sunday,” “I’m Not Your Stepping Stone” and “Daydream Believer” by the group once derided as “the Prefab Four.”

Nesmith provided some of the teen pop group’s most literate songs, from the Dylan-esque wordplay of “Tapioca Tundra” to the heart-on-sleeve bittersweet romantic parting in “Some of Shelley’s Blues” (the latter covered both by Ronstadt and her band, the Stone Poneys, and the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band).

And though many might reasonably assumethat Nesmith’s primary influences were Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie or even Cole Porter, this is not the case.

“I’m definitely a child of Bo Diddley,” he says. “There were these simple sudden truths in the way he wrote that turned into riffs … that were underpinned with his primitive basic rhythmic foundation [in a way] that taught me a lot about how to communicate with a song.”

Not coincidentally, Nesmith’s book has generated a companion Rhino Records compilation CD, “Infinite Tuesday: Autobiographical Riffs — The Music.”

Numerous facets of his long recording career are represented in 14 tracks, from Monkees songs “Papa Gene’s Blues” and “Listen to the Band” to material that blurred the line separating country and rock in the 1960s: “Different Drum,” and his early ’70s solo hits “Joanne” and “Silver Moon” up through “Rio,” a 1977 single that put him on the track to creating music videos for a new generation.

Among the many varied career turns he touches on in the book is the idea he cooked up in the late 1970s for a show he called “Pop Clips,” consisting of 30 minutes’ worth of videos created for various pop songs. There was no outlet for such a thing at the time, but Nesmith was directed to meet with executives at Warner Bros., who were looking for new ideas to program video channels; “Pop Clips” became a template that helped lay the foundation for what would become MTV.

Nesmith, however, had already moved on, producing pet film projects such as “Timerider: The Adventure of Lyle Swann,” an absurdist 1982 time-travel movie directed by his friend, Bill Dear, and director Alex Cox’s acclaimed indie film “Repo Man” in 1984.

Those were financed in part by money left him by his mother, a former secretary who decades earlier had invented Liquid Paper, a company she sold in 1979 for nearly $50 million.

Nesmith also used his inheritance to fund the Gihon Foundation, which supports free live performances, on stage and online, of music, theater works and dance by emerging and established artists, and which Nesmith still oversees.

Although “Infinite Tuesday” is Nesmith’s first formal foray into long-form nonfiction, he has also written and published two novels: “The Long Sandy Hair of Neftoon Zamora” in 1998 and “The American Gene” in 2009.

“I’ve never really been happy as a performer,” he says. “I didn’t mind a little bit of movie stuff and TV stuff — that was OK because there was a certain interior quality to it, even though you were in the middle of a bunch of people.

“I think I’m really cut out for the writer’s life,” he says, sounding not a little surprised at this late-in-life realization. “I like the long hours of solitude and thought. It’s really my cup of tea.”

Follow @RandyLewis2 on Twitter.com

For Classic Rock coverage, join us on Facebook

ALSO

Review: The Monkees celebrate 50 years at Hollywood homecoming

‘Davy Jones deserves a lot of credit’--Monkees co-creator Bob Rafelson

The Monkees celebrate 50th anniversary by teaming with modern pop luminaries for a new album

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.