The power of play: Phil Burgers, aka Dr. Brown, isn’t just clowning around at his L.A. theater

- Share via

Earlier this year, I received an email that contained a link, which led me to a beautiful short film called the “The Passage,” which led me to the Lyric Hyperion Theatre in Silver Lake and the professional doorstep of Philip Burgers, aka Dr. Brown, teacher and clown.

I might have encountered Burgers/Brown sooner had I seen his episode of the 2016 Netflix comedy anthology “The Characters,” or two short episodes on YouTube of “Comedy Blaps,” made for Britain’s Channel 4, or attended one of his several acclaimed appearances at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe.

But it was “The Passage,” created and co-written by Burgers with director Kitao Sakurai (“The Eric Andre Show”) that I saw first, falling in love with its strangeness and simplicity. It moves from tension to release (to tension, and so on), from celebration to horror. There is drumming, there is dancing and there is death, as Burgers’ character is chased, for no clear reason, from a storefront church, to a Japanese bath house, to an African household, onto a Scandinavian trawler. Burgers doesn’t speak at all, and none of the speaking characters speak English. There are no subtitles.

“You want to just be suggestive,” Burgers told me recently, “and then the audience has space to dream around it, and is an active participant in it. Their imaginations are working.”

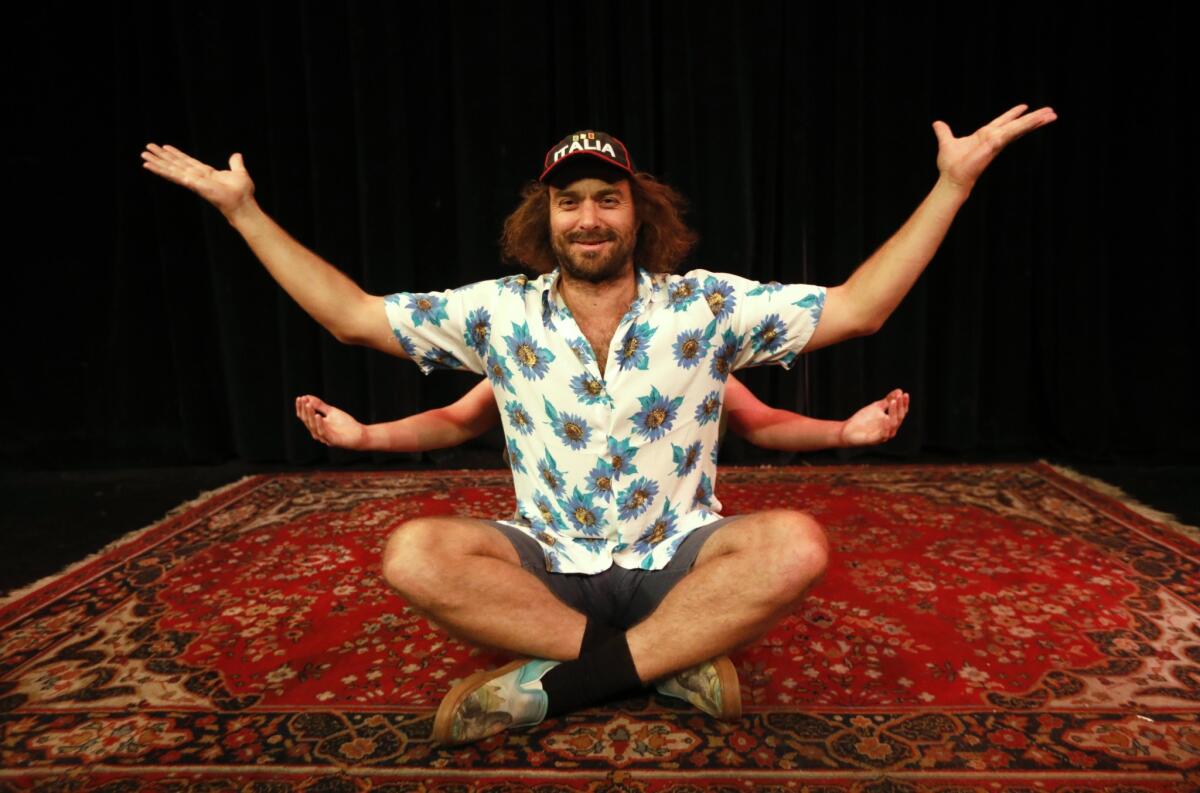

When I say that Burgers is a clown, you should not picture the white face, the red nose, the orange wig of circuses and nightmares. His training is theatrical and European and the sort of thing its practitioners often called “work,” though its goal is play. It is serious and silly, simultaneously. Still, in person, with a thick frizz of hair jutting out from beneath a ball cap, a colorful patterned shirt, shorts with dark socks and an energy that might be described as relaxed restlessness, there is something about Burgers one could call clownish.

“Phil can hide nothing,” says collaborator Chad Damiani. (Damiani and Juzo Yoshida, partners in the clowning duo Jetzo, play Burgers’ mysterious pursuers in “The Passage.”) “He says exactly what’s on his mind; if he’s upset, he wears it through his whole body. He’s, like, a pure clown.”

We were sitting with Burgers on the streetside patio of the Lyric Hyperion Theatre, at the corner of Lyric and Hyperion avenues. Burgers has recently improved the theater, replacing a Plexiglas partition with wood and creating a friendly, protected space within. He was just back from the Venice International Film Festival and a screening of Mexican director Carlos Reygadas’ new film, “Our Time (Nuestro Tiempo),” in which Burgers co-stars.

Burgers, who speaks fluent Italian and Spanish, French “quite well,” “a little bit of Polish” and “a tiny bit of Dutch,” calls himself “a nomad by nature.” He says “The Passage” was born out of “frustration of not traveling and not being exposed to new cultures. I was living in Echo Park in a gentrified neighborhood and going to my coffee shop with a bunch of other people who looked like me. And then I’d drive to Westlake and it’s a totally different culture, people selling things on the street and Mexican churches; it was this whole other life I was not a part of even though I lived so close to it.”

He cites as an inspiration “City of Gold,” Laura Gabbert’s 2015 documentary about the late L.A. Times food critic Jonathan Gold, “where he goes to different parts of L.A. and tastes their food and learns about their culture.”

“I think that Phil has the ability to take ephemeral, instinctual, emotional ideas and find ways of making them concrete and real onstage and on screen while also retaining a sense of mystery,” director Sakurai told me. “Everything that Phil does I think he both understands from a very technical level, but he’s OK with certain things being mysterious and coming out of the ether and not knowing why he’s attracted to them.”

The film has had a run of good and bad fortune. It had its world premiere in February at the Sundance Film Festival (in the television category “Indie Episodic”) and more recently won awards at the L.A. Film Festival, Aspen Shortsfest and the New York Television Festival. (It works as a short film or a pilot, as the occasion demands.)

But last month, as an upshot of the merger of AT&T and WarnerMedia, Super Deluxe, the studio that produced “The Passage” (with Abso Lutely, the production company run by Tim Heidecker, Eric Wareheim and Dave Kneebone), fell to the corporate ax. And the streaming service FilmStruck, which this month began offering “The Passage” for what was meant to be an indefinite run, was struck down as well. Still, you can see it there through November, as well as on the TBS Digital website and its YouTube channel.

Phil can hide nothing. ... He’s, like, a pure clown.

— Chad Damiani

Learning to hear ‘no’

Burgers, 41, grew up in Rancho Palos Verdes; his mother is Italian and his father is from Holland. His road to clowning was long and circuitous; he worked in Long Beach as a “mental health specialist,” doing outreach with the homeless; taught Spanish in San Francisco and Westchester; and was a production assistant before deciding that Hollywood “felt like a very unhealthy breeding ground as a young artist. It’s a good place to come when you know what you have to offer, but if you want to discover it, it feels really destructive to that process. That’s why I left, to go find my voice.”

He was 28, working in Italy as a bicycle tour guide, when he traveled to Scotland to check out the famed Edinburgh Festival Fringe and saw a show by a Philadelphia group called Pig Iron. “[It] really blew my mind,” Burgers said. “It was a silent show, and it made me laugh, it made me cry, it was so beautiful. And I asked them afterwards, ‘What is this?’ They said, ‘This is clown.’ ”

They directed him to the École Philippe Gaulier outside Paris; Gaulier had trained Roberto Benigni, Sacha Baron Cohen and Emma Thompson.

“It’s not an academic approach at all,” Burgers said. “You just have to come onstage and make us laugh or just be beautiful, and most of the time [Gaulier] just tells you how [bad] you are.”

“I’d always been this gregarious, outspoken, extroverted, entertaining type person and thought I was really funny. And I came to school with that kind of, ‘All right, I got it,’ and he just killed it. The first four months were about me realizing I’m not really good, and when I realized I wasn’t good, that’s when things started to come.”

Accordingly, anyone interested in taking classes with Burgers will find this warning posted on the theater’s website:

“Come learn how not to take your self so seriously, be stupid and relatively free, and have fun with an audience. Note — this sounds fun and easy, but the workshop is actually very difficult — seriously. I (Dr. Brown/Philip Burgers) am often NOT nice and some people don’t like this approach, but if you can handle admitting that what you just did on stage was horrible and nobody really laughed, then perhaps you’ll get something out of this class.”

“It’s called ‘via negativa,’ ” Burgers said, “which is ‘by way of no.’ It’s saying no to the work until there’s a yes moment. Which is very different than the American approach, which is much more through positive reinforcement: ‘That’s so great, keep going.’ I’m also an American from Southern California, so positive reinforcement just naturally finds its way in. I am harsh, but it’s never no to you personally; it’s no to the work. But because the work is so personal, the lines are blurred.”

When I say that Burgers is a clown, you should not picture the white face, the red nose, the orange wig of circuses and nightmares.

“I think it’s a really important thing, to protect this community of spirit, of having it not be too competitive,” Burgers said. “Clown work helps because you just admit you kind of suck. Once that happens, everybody’s on each other’s side.”

After years working abroad, Burgers returned to the states in 2015 to make his episode of “The Characters,” an intricately choreographed single-shot circular journey along a block in Queens, in which he dodges in and out of wigs and costumes and characters, apartments and cafes and bars, gathering strangers as he goes. In its traveling structure, it prefigures “The Passage,” and though Burgers speaks in it, it’s a full-body performance.

Moving back to L.A., he soon found his way to the Lyric Hyperion, where he began to perform and help develop other performers’ shows and where “a troupe started to develop,” made up of “the people who inspire me the most, and who surprise me the most, that I’ve found so far.”

Eventually he became the theater’s creative director and, after former owner Mark Sherman moved out of state early this year, its owner.

“I just want this to be a safe place for failure,” said Burgers, who recently converted the theater into a tax-exempt nonprofit, “without the pressures of the commercial industry. I think the nonprofit ethos fits well with artists.”

“The Lyric provides a platform no other theater in Los Angeles provides,” said Natalie Palamides. Her one-woman shows “Laid,” about a woman who lays an egg every morning and has to decide whether to raise or eat it, and “Nate,” in which she plays a man to explore issues of consent, were directed by Burgers. And like Burgers’ own shows, they were Festival Fringe hits. “It’s really a home for artists to explore and to fail, whereas other theaters make you go through a process to put up shows in which they want to make sure you’re not failing — they make you submit an application and a script — where at the Lyric they let you try out whatever your artist heart and brain desires. They encourage people to fail, because through failure is where we find the best things.”

Failure, of course, is only a place to start. “I want you to do bad,” said Burgers, “but with the intention of making great work eventually.”

“Phil always pushes you to keep refining and developing your work,” Palamides noted. “He doesn’t let you sit in mediocrity, and he’s always encouraging you to look for ways to subvert the material instead of just going for the cliches and the tropes. Even after we take the shows to Edinburgh, I’ll still get pages of notes after every show.”

Spirit of play

The Lyric Hyperion Theater is not the only place theatrical clowning is done or taught in Los Angeles. There are clown shows at the Clubhouse on Vermont Avenue and the Pack Theater on Santa Monica Boulevard, and classes at Cirque Du Soleil vet John Gilkey’s The Idiot Workshop and at the Clown School, whose David Bridel was a student of Gaulier.

And it’s not all clowning at the Lyric Hyperion. There are stand-up nights, variety shows, plays, music, screenings. Sunday mornings there’s a drag brunch; Sunday afternoons, a “piano bar” that brings in “the older generation of the neighborhood.” It’s also a hangout; coffee and alcohol and some simple food are served. “The mornings are busy,” said Burgers, “and at night it’s packed out here.”

As a performer, Burgers is directing his energy into taking “that clown-y kind of playful stupidity, the spirit of play and irreverence and surrealness and bringing it into film. I’m not so interested in doing solo stage stuff anymore. I did that for many years — cracked that nut.”

Nevertheless, he’ll perform his unpronounceable one-man show, “Befrdfgth,” at the Lyric Hyperion Theater for three nights in December.

“They’re prop-based and physical and really dumb,” he says of his shows. “I come on with this” — he’s holding a bottle of water — “and pretend to drink and it falls all over me. I’ll play with the audience too. I’ll pretend that I’m swimming and need a lifeguard, and they have to save me. Lots of visual gags and lots of action; there are no clever jokes in it. It’s all a relationship between me and the audience and then playing with that relationship.”

“There’s something very primal and innocent about clowning,” Damiani told me. “It’s getting to this place where the audience can see everything you’re thinking and feeling, and it’s all happening, no different than a puppy or a baby; we wear it all in our body and on our face. And the choices we make, no matter how dumb, the audience is on board because we’re connected with them.”

“So much of this work is about receiving and being open,” said Burgers, “and not like performers where we see, ‘Yes, I’m a performer’ and they give so much. This is just the opposite: I listen, I watch, and with that we go somewhere.”

The Lyric Hyperion

What: Shows, classes

Where: 2106 Hyperion Ave., Los Angeles

Info: (213) 928-2299, lyrichyperion.com

ALSO

Carlos Reygadas’ films search for authenticity beyond reality

The fresh ‘The Characters’ and the stale ‘Flaked’ have Netflix in common and little else

Review: In ‘Homecoming,’ a Julia Roberts acting question and the dark fun of data-mining tyranny

Follow Robert Lloyd on Twitter @LATimesTVLloyd

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.