Here’s Peter Lassally: A life in late-night television

- Share via

Late-night television, busier than ever (and at its best, better than ever) with talk shows and comedy, has been in the news again lately, with the hand-over of “The Tonight Show” from Jay Leno to Jimmy Fallon officially announced for next spring — a change in stewardship that will also take the show back to New York from Burbank.

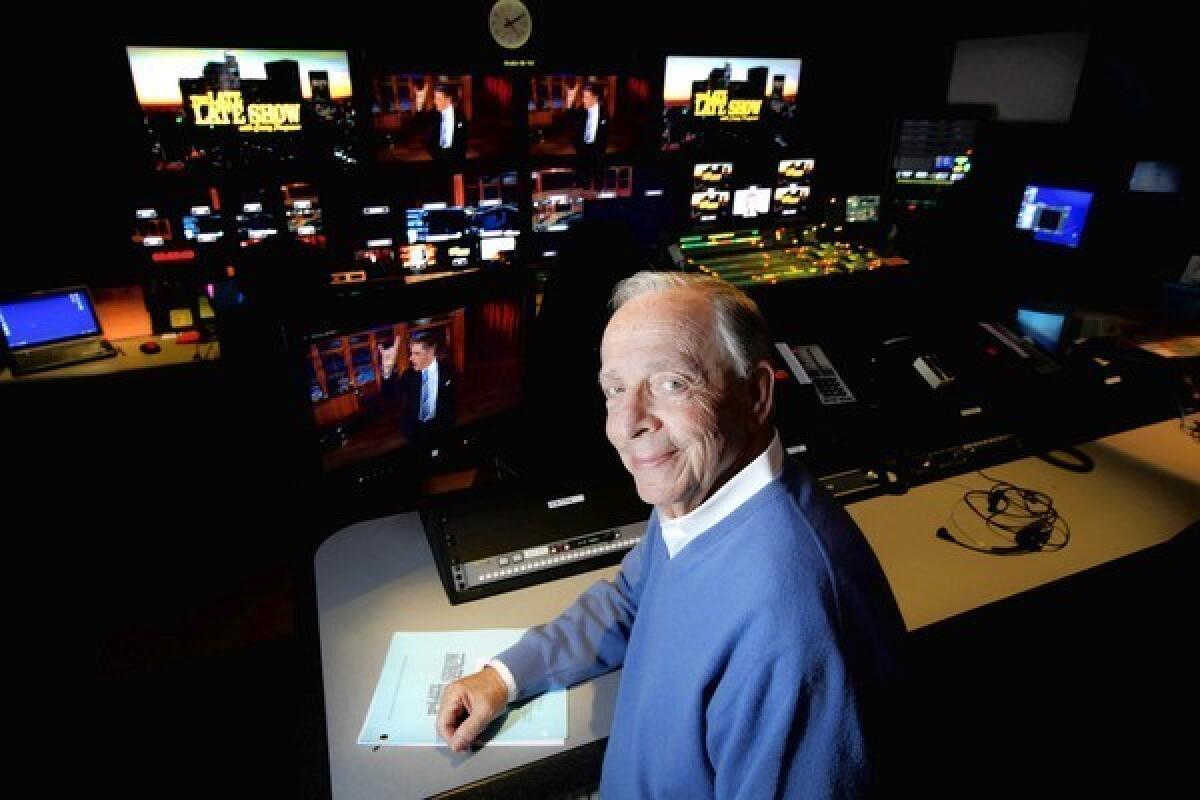

The man who brought “The Tonight Show” west in the first place is producer Peter Lassally, who wanted to live in Los Angeles and in 1972 convinced Johnny Carson that California was the place he ought to be. Lassally, 80, is now producer of the singular “The Late Late Show With Craig Ferguson”; when I interviewed Ferguson in 2010, he told me that the person I really should be talking to was Lassally. Finally, I did.

It’s a Friday afternoon in the complex of unassuming offices that make up the Television City headquarters of the Ferguson show and the local branch of the company that makes it, David Letterman’s Worldwide Pants Inc. Lassally was fresh from a booking meeting.

PHOTOS: Classic ‘Tonight Show’ moments

“That’s the hard part of the job,” he said, “because there are three 11:30 talk shows which come first on everybody’s agenda, and then God knows how many at 12, 12:30. So you’re constantly competing for basically the same group of people; and now they sometimes only do the campaign in New York, they don’t come to L.A. So it’s a very small group that you’re fighting for.”

Lassally, whose TV career runs back to Arthur Godfrey, who ruled the medium in the 1950s, is probably the most experienced man in late night — and as the man closest to the men behind the desk, one of the most important. He worked with Carson for 23 years before going on to Letterman, shepherding his move from 12:30 a.m. to 11:30 p.m. It was Lassally who suggested to a retired Carson that he send some of the topical jokes he was writing in his retirement to Letterman to use in his monologues.

He also pioneered the 12:30 slot for CBS, with “The Late Late Show,” originally with Tom Snyder (“a complete original, and a true broadcaster”), and sometimes guest-hosted by Jon Stewart.

“I’ve been very lucky that I’ve worked with really talented people almost all my life,” Lassally said. “But I have a good eye for talent. I think that’s my biggest talent, if not my only talent. And so there is a comfort between the host and me, and trust and respect. I’ve learned things from them, and they’ve learned things from me.”

“I don’t think there’s any question that those shows have guests that tend to have the right chemistry with the host because of Peter Lassally,” said Garry Shandling, who met the producer in 1981 when he guested on “The Tonight Show” and who got to know him well as a regular substitute for Carson.

“He has an innate ability to sense when someone’s going to get along with the host. The joke used to be that he’d look at a comic and say, ‘Well, Johnny won’t like him,’ but what that’s really saying is, ‘That’s not the show we’re producing.’ He’s got a point of view, and it’s a very subtle point of view. He’s got a warmth about him and yet gets his point across — he’s very kind and very direct. “

First impression

“He was rather dignified, vague and a distinguished gentleman,” Ferguson recalled, by email, of his first impressions of the man he has worked with for the last nine years. “Perhaps a little doughty — and probably a genius. I wouldn’t be interested in doing the show without him.”

PHOTOS: Hollywood Backlot moments

Lassally is soft-spoken but not exactly reserved. He laughs easily and often. But he doesn’t feel the need to talk about himself, and he doesn’t like the spotlight, though his life has been remarkable enough that Ferguson wanted to make a movie of it. (“I’m sorry,” Lassally told him, “I can’t cooperate with that.”)

On occasion, he will agree, reluctantly, to appear in public. After Carson died, Letterman persuaded Lassally to come on “Late Show” and talk about his old boss. “I was so scared,” he told me, describing himself, inaccurately, as “inarticulate.” I pointed out that he got laughs. “Believe me,” he replied, “I was totally numb.”

On “The Tonight Show,” he was teamed with the flamboyant Fred de Cordova, who died in 2001, the man most people think of as that show’s producer. “We were good and bad together,” Lassally recalled. “I liked the work, he liked the schmoozing, and was great at it. We didn’t think alike when it came to how to produce the show, so it wasn’t always easy. But we had lunch every day together for more than 20 years.”

It was at “The Tonight Show” that Lassally “really put my likability factor into practice, where I said, ‘I don’t want to just book the person that’s hot right now.’ That was probably my major influence, in that we would not go after the same people as the other shows. I would book an author or an opera singer or a magician. I wanted it to be a little bit of everything.”

At “The Late Late Show,” he continues to strive for range, noting that “because of my age, I will book people that are in their 60s, which is ... forbidden in the television industry. We can’t have three or four old people in one week, because you need to go for that young audience.”

Still, his main concern is that the guests “be likable and interesting and not too actor-y. Especially on a 12:30 show, you’d better make it interesting and funny and comfortable. If somebody walks out and is obnoxious and working to the audience instead of to the host, you’ll say, ‘Oh, I think it’s time to go to sleep.’”

Lassally was born in Hamburg, Germany, in 1932; his father was in the coffee business. Young Peter was a “lazy” violin prodigy: “I didn’t know how to read music, but I could memorize something if I heard it three times.”

In 1938, the family, who was Jewish, fled to Holland. The Lassallys’ objective was eventually to reach England. “Fishing boats were smuggling people out and three times I think we were scheduled to go and it was canceled at the last minute because ... they would have shot you.”

The Nazis followed them into Holland; for a time, the family lived in Amsterdam, under a growing set of restrictions. (Anne Frank was a high school classmate of Lassally’s older sister, who reported that “she was not liked by anyone.”) “They created new limitations all the time. I remember, we went to some soccer stadium and everyone had to turn over their bikes — I mean, who thought of that?”

Then, starting in 1943, not long after the death of his father from cancer, Lassally, his sister and his mother were interned for a year and a half at Westerbork in Holland and for an additional nine months at Theresienstadt, a “model” camp in what is now the Czech Republic that the Nazis used for propaganda purposes. But, Lassally said, “convoys of trucks and trains were shipping people off every day.”

“You’d be called out of the barracks in the middle of the night and stand there, and you’d say, ‘This is it, now we’re being shipped out to another camp.’ And two hours later, you could go back in. You were totally off balance the entire time.”

Was there anything he learned from his time there that helped him in his career?

“You have to grow up fast,” he said. “So I was probably mature for my age. And somewhere along the way, I learned not to be intimidated by either big titles or big stars.”

After the war, the family moved to New York. Lassally worked as an usher at Radio City Music Hall and then at NBC as a page, which at that time was an entry-level broadcasting position.

“People in television in those days either came from radio or the theater,” he recalled. “Nobody knew what they were doing, although they were smart, talented people who were creative and cultured. Ratings weren’t as important as they are now, and decisions were made creatively rather than what would reach 18 to 49.”

At NBC, where he met his wife, Alice, he worked first in radio, as a producer on “Monitor,” a news-culture-and-variety omnibus that lasted the entire weekend, and “Nightline,” where he helped introduce a generation of comedians that included Mort Sahl, Mike Nichols and Elaine May, and Shelley Berman. “That’s really where I started to blossom,” he said. “I felt very comfortable with comedy.”

On the job

Comfort is at the heart of what Lassally provides: creating a space in which big, complicated personalities under pressure can do their work. He learned, beginning with Godfrey, that “if you are really, really talented, you have to be different. You’re not a regular person. You’re going to be neurotic, or narcissistic, and that just comes with the territory.

PHOTOS: Classic ‘Tonight Show’ moments

“The most normal of the ones I’ve worked with was Carson. He was not all show business; he was well-read, and we would talk about problems of the world. Not narcissistic, and not really crazy. He was moody — he’d come in in the morning sometimes and you’d think, ‘Oh, my God, what is it this time?’ You didn’t know if it was another marriage falling apart or whether it was the job. But he was not difficult at all.”

Of Ferguson, he said, “He’s a man of many moods, not unlike Johnny. He can come in and you say, ‘Uh oh, there’s a black cloud over there.’ And he can be the sweetest man at the same time.”

Before Ferguson auditioned to replace then-”Late Late Show” host Craig Kilborn, the producer got word that the Scottish comedian and actor was doing it as “a lark.” “I don’t want you to do this for fun,” Lassally told him. “I think you’re the guy, and I want you to think seriously about this.”

Ferguson did, and the two went on to create the most original and spontaneous show in late night.

Lassally admires the host’s willingness to “try different things on the show, different structures,” to “deconstruct the format all the time. All the other hosts really want to be another Johnny Carson or another Dave Letterman. And Craig isn’t looking for that.”

“Every performer jokes about the fact that something like ‘The Tonight Show’ is overly prepared,” said Shandling. “You have a pre-interview and an outline, and they stick to it; I think Peter’s very supportive of going off that outline and just talking to the person.”

“There are some notes,” Lassally told me. “Craig looks at them and goes, ‘Fine,’ and doesn’t use them 95% of the time; it’s really conversation on the spot.”

The best advice Lassally has given him, Ferguson said, was “to relax and tell the truth. And don’t do my creepy laugh.”

On a typical show day, Lassally said, the two will meet in the afternoon to discuss the night’s guests and “shoot the breeze. We’ll talk about today’s news or politics or anything in the world; you know, he reads everything. Then we do the show, and after the show we spend 20, 30 minutes talking about what worked, what didn’t work, and whether we liked the person or not.

“When we first started to work together, Craig wanted to know about my background. He listened to all my adventures and one day I came into the office and he said. ‘I have a gift for you’ — and it’s that painting that’s hanging up there.”

He points to a framed picture that faces his desk from the far end of the room. “It’s the ship I came on from Holland to America.”

PHOTOS, VIDEOS & MORE:

Real places, fake characters: TV’s bars and eateries

PHOTOS: ‘The Ellen DeGeneres Show’ through the years

PHOTOS: Violence in TV shows

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.