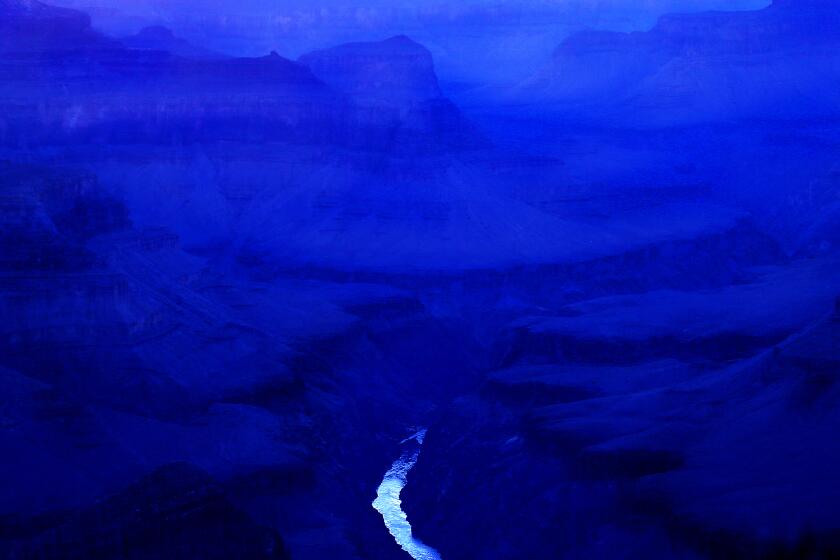

As drought crisis deepens, government will release less water from Colorado River reservoir

- Share via

After years of severe drought compounded by climate change, the water level in Lake Powell, the second-largest reservoir on the Colorado River, has dropped to just 24% of full capacity and is continuing to decline to levels not seen since the reservoir was filled in the 1960s.

In an effort to boost the shrinking reservoir, the federal government announced Tuesday that it will hold back a large quantity of water this year to reduce risks of the lake falling below a point at which Glen Canyon Dam would no longer generate electricity.

“Today’s decision reflects the truly unprecedented challenges facing the Colorado River Basin and will provide operational certainty for the next year,” Tanya Trujillo, the federal Interior Department’s assistant secretary for water and science, said in a statement announcing the measures.

It is the first time the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation has invoked its authority to change its operations in this way at Glen Canyon Dam on the Arizona-Utah border. The agency said the plan is intended to protect infrastructure at the dam and its ability to generate hydropower and will ensure that water supplies continue to be available for the nearby city of Page, Ariz., and a portion of the Navajo Nation.

The plan is aimed at reducing the risks of Lake Powell falling to critically low levels. The measures will involve releasing about 500,000 acre-feet of water from Flaming Gorge Reservoir, which is located upstream, and leaving an additional 480,000 acre-feet in Lake Powell by reducing the volume of water released from Glen Canyon Dam this year.

For comparison, California, Arizona and Nevada used 6.8 million acre-feet of Colorado River water in 2020.

To water resiliency advocates at the U.N. climate conference, the Colorado River stands out as ‘the best example globally of how things can go badly.’

The Colorado River supplies water to nearly 40 million people in cities from Denver to Los Angeles and to farmlands from the Rocky Mountains to the U.S.-Mexico border. The river has been chronically overused, and its reservoirs have fallen dramatically since 2000 during a severe drought that scientific research shows is being intensified by global warming.

The federal government last month proposed the plan to combat declines in Lake Powell to the states in the Colorado River Basin. In a letter, Trujillo asked the seven states that depend on the river for their input on the plan.

“We believe that additional actions are needed to reduce the risk of Lake Powell dropping” below a level of 3,490 feet above sea level, Trujillo said in the letter.

Trujillo warned that below the threshold of 3,490 feet, Glen Canyon Dam’s facilities face “unprecedented operational reliability challenges, water users in the Basin face increased uncertainty, downstream resources could be impacted, the western electrical grid would experience uncertain risk and instability.”

The level of the reservoir on the Arizona-Utah border now stands about 32 feet above that threshold.

“We are approaching operating conditions for which we have only very limited actual operating experience,” Trujillo said in the letter.

Representatives of the seven states responded in a letter on April 22, saying they agreed that “additional cooperative actions should be taken this spring to reduce the risk of Lake Powell declining below critical elevations.”

The state officials said they support the government’s plan to release less water from Lake Powell “to reduce the risks we all face.”

For the first time ever, Southern California water officials will limit outdoor watering to just once a week in certain areas beginning June 1.

To cut the total annual amount released from Glen Canyon Dam to 7 million acre-feet, the Bureau of Reclamation is keeping 350,000 acre-feet of water in Lake Powell that was already held back earlier this year, and will hold back an additional 130,000 acre-feet by the end of September.

David Palumbo, the bureau’s acting commissioner, praised the quick response by the seven states. He said while carrying out these short-term measures, “we recognize the importance of simultaneously planning for the longer-term to stabilize our reservoirs before we face an even larger crisis.”

Trujillo said everyone who relies on the river “must continue to work together to reduce uses and think of additional proactive measure we can take.”

Even with less water flowing downstream this year, managers of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California said they have stored enough Colorado River water to fill the aqueduct for now and will not have to limit how much is delivered to the region.

“Drought and climate change are creating incredible challenges that must be addressed in both the immediate and long term,” said Adel Hagekhalil, the district’s general manager. He said that while the reduced releases at Glen Canyon Dam “will not impact our ability to deliver Colorado River supplies this year, they are a reminder that the Southwest is in uncharted water territory.”

Hagekhalil said the district is urging all Southern Californians “to immediately cut back their water use by 20% — or more in some areas — to stretch available supplies and storage.”

The MWD imports water from the Colorado River and the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, serving agencies across six counties that supply 19 million people — about half the state’s population. The supplies from the Delta, delivered through the State Water Project, have been reduced to just 5% of full allocations this year.

The shortage on the State Water Project last week prompted the MWD to order water restrictions in areas that depend heavily on those supplies. But cities that depend largely on Colorado River water won’t face mandatory restrictions.

Areas that get water from the Colorado River or other sources will be spared from restrictions, at least for now. The strategy has divided experts.

“On the Colorado system, we’ve prepared for years like this, so we can take delivery of Colorado River water into the future,” said Bill Hasencamp, MWD’s manager of Colorado River resources.

“We might start having limits on the Colorado,” Hasencamp said. “But that’s still a few years away before we’re anticipated to get to that level. So for the next two to three years, at least, we have enough supplies stored to fill the aqueduct.”

The Metropolitan Water District’s approach, with mandatory water restrictions in some areas and none in others, has been criticized by some.

Felicia Marcus, a researcher at Stanford University and former chair of California’s state water board, said she thinks leaving areas that depend on the Colorado River without mandatory restrictions, and not cutting back across the region, is like “high-stakes gambling.”

“Even if they’ve got enough for this year, the question is, do they have enough for the next three to five years?” Marcus said. “To me, it seems that we need to take more dramatic action.”

Over the last several years, state and federal officials have repeatedly negotiated deals to try to reduce risks of reservoirs falling to critically low levels.

In 2019, representatives of the seven states gathered on a terrace overlooking Hoover Dam and signed a set of agreements called the Drought Contingency Plan, which included a pact between California, Arizona and Nevada to take less water from the river to try to limit the declines in Lake Mead, the nation’s largest reservoir.

Last summer, the federal government declared a water shortage on the Colorado River for the first time, triggering substantial cutbacks in water deliveries to Arizona, Nevada and Mexico.

With the reservoirs continuing to decline, water officials from California, Arizona and Nevada signed another deal in December to significantly reduce the amount of water they take, aiming to keep an extra 1 million acre-feet of water in Lake Mead over two years.

As Colorado River levels continue to drop, water agencies are working with local growers to leave some fields fallow in exchange for cash payments.

Some of those reduction will come through payments for water conservation in farming areas, including payments to growers who leave some fields dry and unplanted. Tribes have also agreed to leave water in Lake Mead in exchange for payments.

The latest short-term plan is “yet another kind of a Groundhog Day on the Colorado River,” said Bart Fisher, a farmer who is a member of California’s Colorado River Board. The last few years have brought repeated attempts that turned out to not be enough, he said, and the states’ representatives need to start negotiating a new set of rules for managing shortages after 2026.

“The consensus, in California at least, is let’s stop playing whack-a-mole,” Fisher said.

“Let’s sit down and start seriously negotiating the next set of guidelines,” he said. “The clock is ticking. We need to get going.”

Jennifer Pitt, Colorado River program director for the National Audubon Society, wrote in an article last month that the Colorado River Basin is inching closer to “Day Zero,” a term that arose in 2018 when Cape Town, South Africa, faced a real risk of running out of water.

“In recent days, state and federal officials have announced plans to address the immediate crisis. These plans will help, but only to avert the immediate danger looming over the basin for the current year,” Pitt wrote. “They do nothing to decrease the unrelenting risks of Colorado River water supplies and demands out of balance, because all they do is move water from one place to another.”

She stressed that climate change is drying out the Colorado River and that in the last two decades the river’s flow has been about 20% less than the average flow in the 20th century. The conditions in the watershed today, Pitt said, are likely to worsen over the coming decades.

“What’s needed now, urgently, is for federal and state water managers to work, in partnership with tribes and other stakeholders, to take the steps necessary to build confidence in the enduring management of the Colorado River,” Pitt said. “This will require focus and dedicated resources to develop and implement plans that put water demands into balance with supplies.”