What is causing the parade of storms battering California?

- Share via

California has gone from one extreme to another, from extreme drought and empty reservoirs to too much rain all at once. Beginning on New Year’s Eve, a parade of punishing storms has hit the state, causing widespread flooding and destruction. Tragically, at least 19 people have been killed and the toll in damage is about $1 billion, with more storms forecast. Southern California is expecting additional rain this weekend.

What caused this drought-to-deluge turnabout?

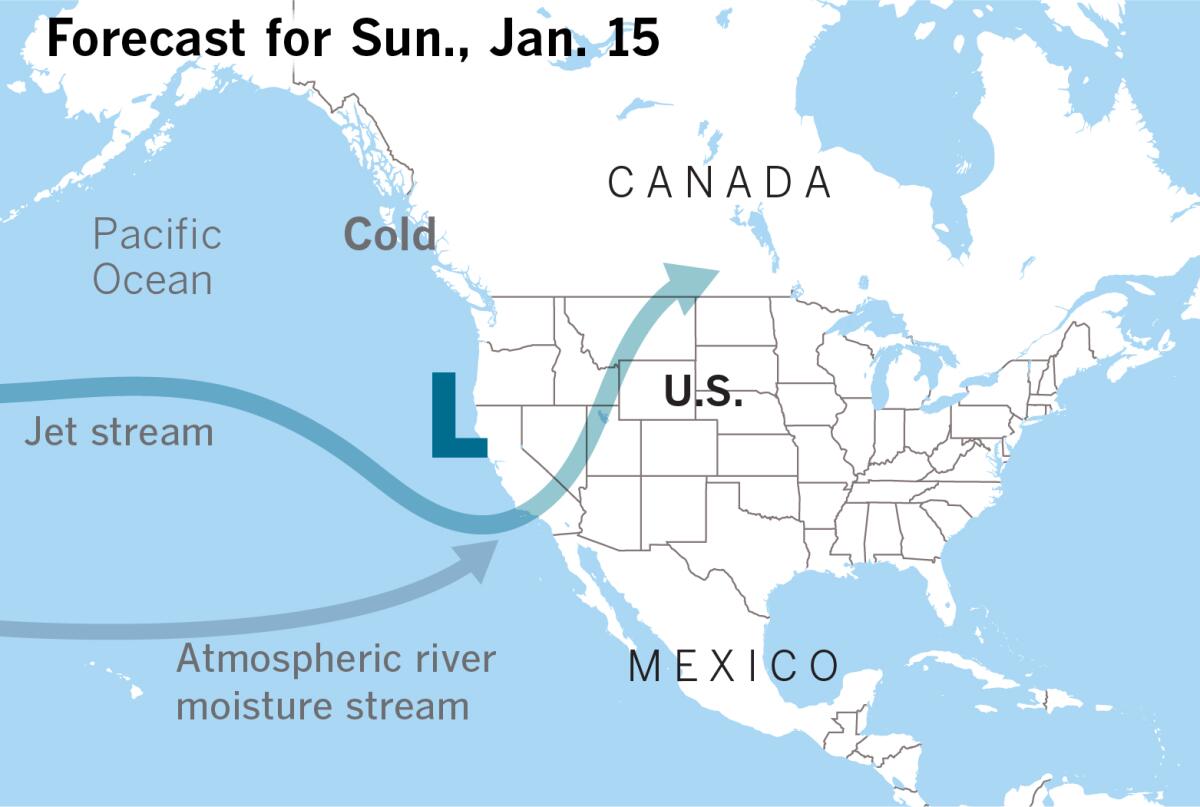

The short answer is the location of the jet stream or storm track — a belt of strong winds high in the troposphere where airliners fly. “It has been parked across the Pacific with multiple low-pressure systems rippling along over the last few weeks,” said Eric Boldt, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Oxnard.

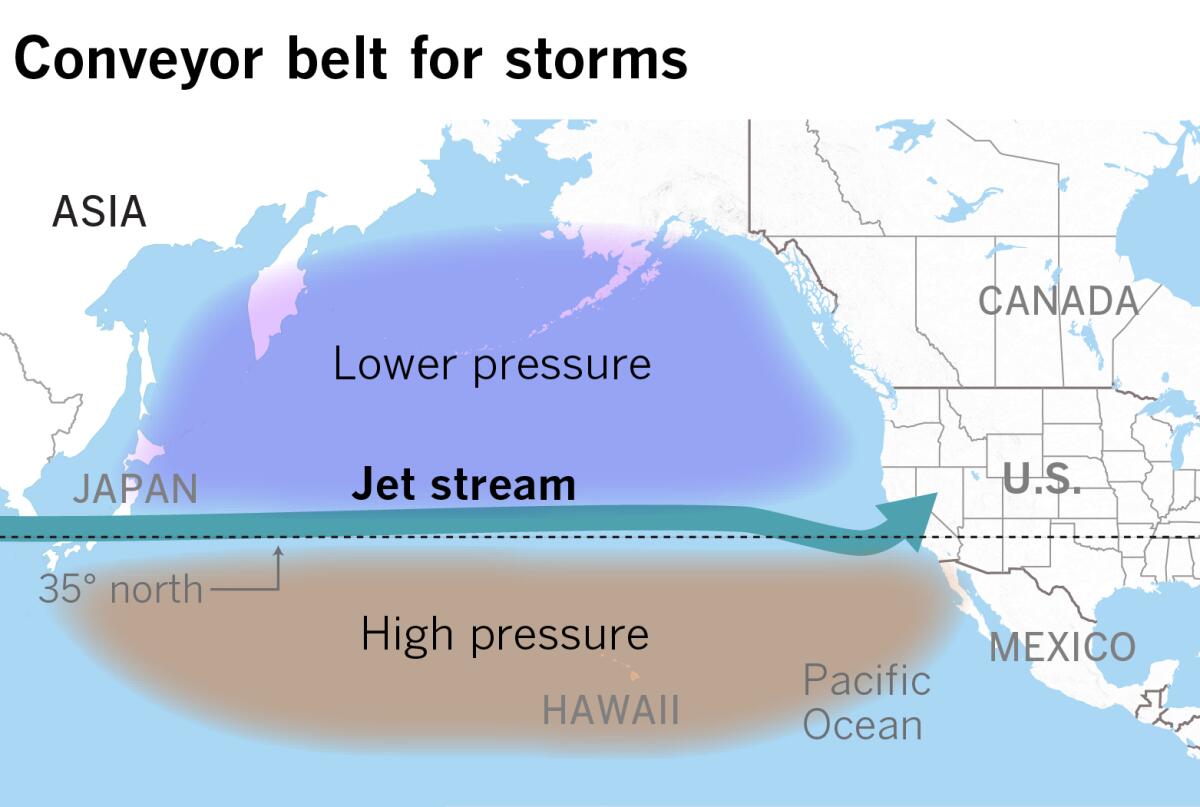

The jet stream pattern this winter is very unusual for current La Niña conditions, said Alex Tardy, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in San Diego. It looks more like La Niña’s unruly sibling, El Niño, as it barrels across the breadth of the ocean, from west to east, along about 35° north latitude, on average.

Traditionally, La Niñas are associated with dry winters in Southern California.

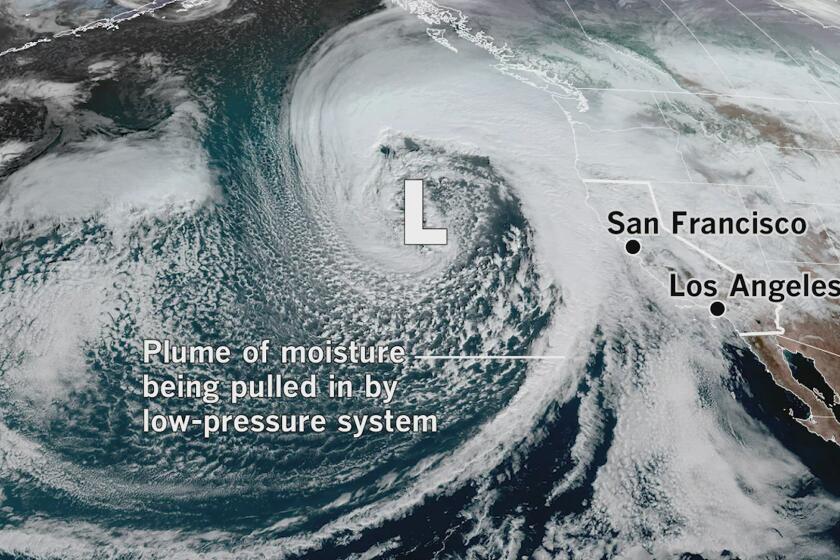

It’s not unusual for storms to move along the jet stream. It’s the position of that moving belt that has been a key factor this winter. This jet stream is like a moving sidewalk at the airport, where storms can pick up baggage along the way. Moisture is plentiful in the western Pacific, where waters are warmer than usual because of La Niña, and storms can easily grab more as they pass by the tropics on their eastward track. They tap into moisture from areas around Hawaii, sweeping it along in atmospheric rivers as they head toward California.

Atmospheric rivers are concentrated streams of water vapor about 100 to 250 miles wide in the middle and lower levels of the atmosphere. These “rivers in the sky” can transport enormous amounts of often-beneficial moisture. On average, about 30% to 50% of annual precipitation on the West Coast comes from a handful of atmospheric rivers. But potent ones can cause extreme rainfall with catastrophic flooding and mudslides. When they arrive in quick succession, as has been the case in recent weeks, it can be overwhelming: Too much of a good thing for a drought-stricken state. Like trying to fill a champagne glass with a fire hose, to use retired Jet Propulsion Laboratory climatologist Bill Patzert’s analogy.

Weather patterns over the Pacific since Dec. 20 found the jet stream to be in what meteorologists call a zonal pattern, flowing straight west to east, with a region of upper-level lower pressure to the north and an area of high pressure to the south, closer to Hawaii. Storms on this route tend to grab warmer moisture as they barrel across the ocean in expressway fashion, one after another.

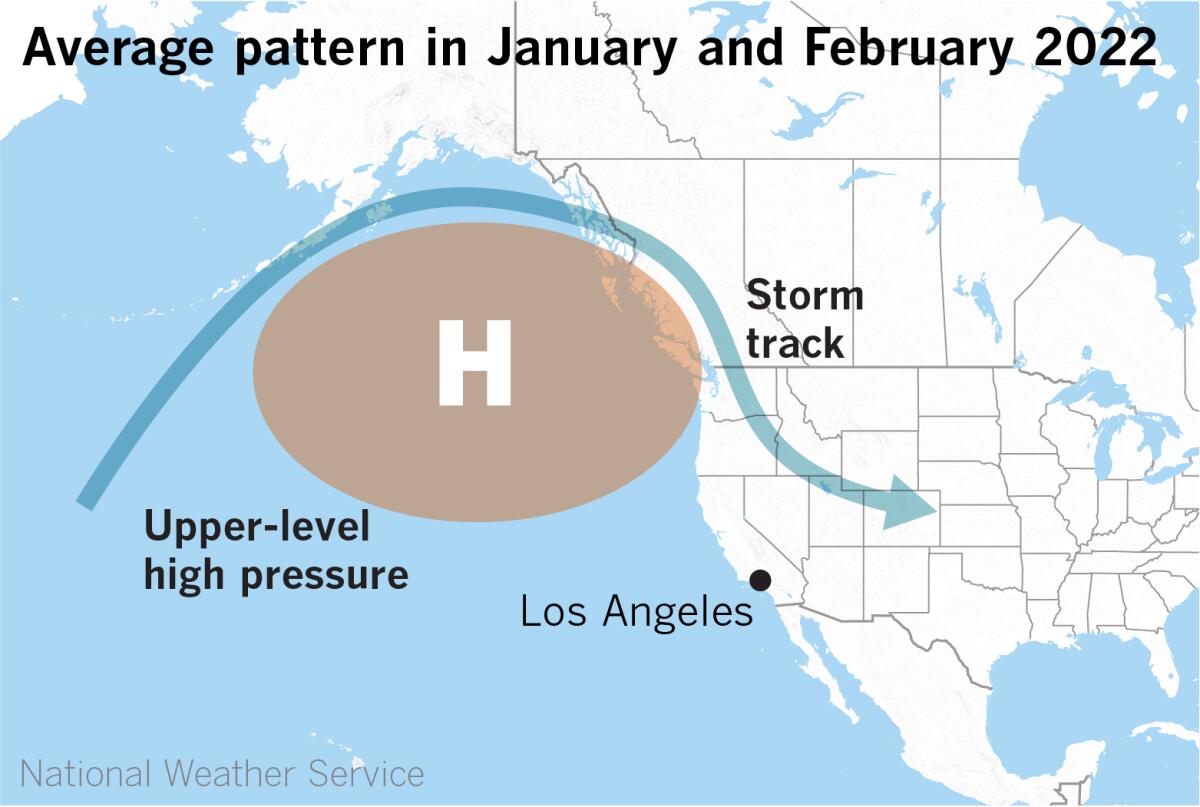

This is significantly different from the patterns that brought the Southland a wet December 2021, then a a record-dry January and February 2022.

In December 2021, the upper-level high situated in the North Pacific — one byproduct of a La Niña atmosphere — backed away to the west by just enough to allow storms from the Gulf of Alaska to plummet down the West Coast over water. This upper high-pressure system has been blamed for blocking storms from reaching a parched Golden State, leading to consecutive dry winters in California. Storms moving south over the ocean stock up on moisture, resulting in more rain.

Then, in January, the high shifted back to the east, slamming the storm door shut for Southern California, resulting in a record-dry January and February — months that are normally the state’s wettest.

Storms riding along the storm track were shunted inland, moving over the Intermountain West or the Rockies. These are called “inside sliders.” This pattern is conducive to Santa Ana winds in Southern California, where winter wildfires broke out in February. The rain-starved state had to contend with dry conditions and above-average warmth, and a heat advisory was issued because of predicted highs of 85-90 degrees when Super Bowl LVI was played at SoFi Stadium in Inglewood on Feb. 13.

Such conditions are more typical of La Niña, the cool phase of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (abbreviated as “ENSO”) climate pattern. This is the third consecutive winter that’s firmly in La Niña territory, based on conditions in the ocean and atmosphere in the tropical Pacific. La Niña is forecast to persist, with a 50-50 chance of conditions turning neutral in the January-to-March period.

Conditions in the state are nevertheless entirely different this year, compared with the previous two La Niña winters. As Tardy points out, snowpack is twice average right now, and about 310 inches has accumulated at Mammoth, which is more than any of the three prior seasons there.

While atmospheric rivers can cause flooding and mudslides, many are weak and can provide beneficial rain to drought-stricken California.

So La Niña typically means warm, dry conditions in Southern California and the Southwest, but it’s not always the case.

Central California continues to be the primary focus of this El Niño-like jet stream position, and the part of the state that has received the most above-average precipitation. For reference, San Luis Obispo sits just north of 35° north latitude, the line that the persistent, elongated Pacific jet stream has followed across the ocean in recent weeks. The Santa Barbara area, a bit to the south, has received 12-15 inches of flooding rain.

Even though California has been deluged with rain in recent weeks, it doesn’t compensate for more than two decades of drought, which played a big part in record-shattering fire seasons.

Atmospheric river moisture plumes in the lower and middle levels of the atmosphere, when they encounter mountains, are forced to rise quickly, enhancing the rainfall. This collision and lifting effect means that mountains wring the maximum moisture out of atmospheric rivers. This frequently causes mud and debris flows. Hillsides blackened and denuded by fires are the worst possible place for heavy rain to fall. And heavy rains at higher elevations mean the water has to go somewhere, and that’s always downhill.