How a perfect storm of climate and weather led to catastrophic Maui fire

- Share via

Drought. Howling winds. Plummeting humidity. Tinder-dry grass. A historic city of exposed wood structures in a thirsty rain shadow.

To a Californian, many of the factors that appear to have coalesced into a catastrophic fire that killed at least 36 people on Hawaii’s Maui island are all too familiar. Yet for a tropical region that traditionally sees only mild wildfire activity, the chance interaction of terrain, weather, building development, vegetation and the growing force multiplier of climate change have seemingly rewritten natural history.

Researchers note that although any one of these factors would typically lead to increased fire risk, all of them together created a tinderbox that was primed to explode. All they needed was a spark.

A Maui tourist hub looks like a wasteland, with homes and entire blocks reduced to ashes in one of the deadliest U.S. blazes in recent years.

The exact cause of ignition remains under investigation, but what is known is that roughly 80% of Hawaii is under abnormally dry conditions, with more than 14% in a moderate drought and nearly 3% in a severe drought, according to recent data from the U.S. Drought Monitor.

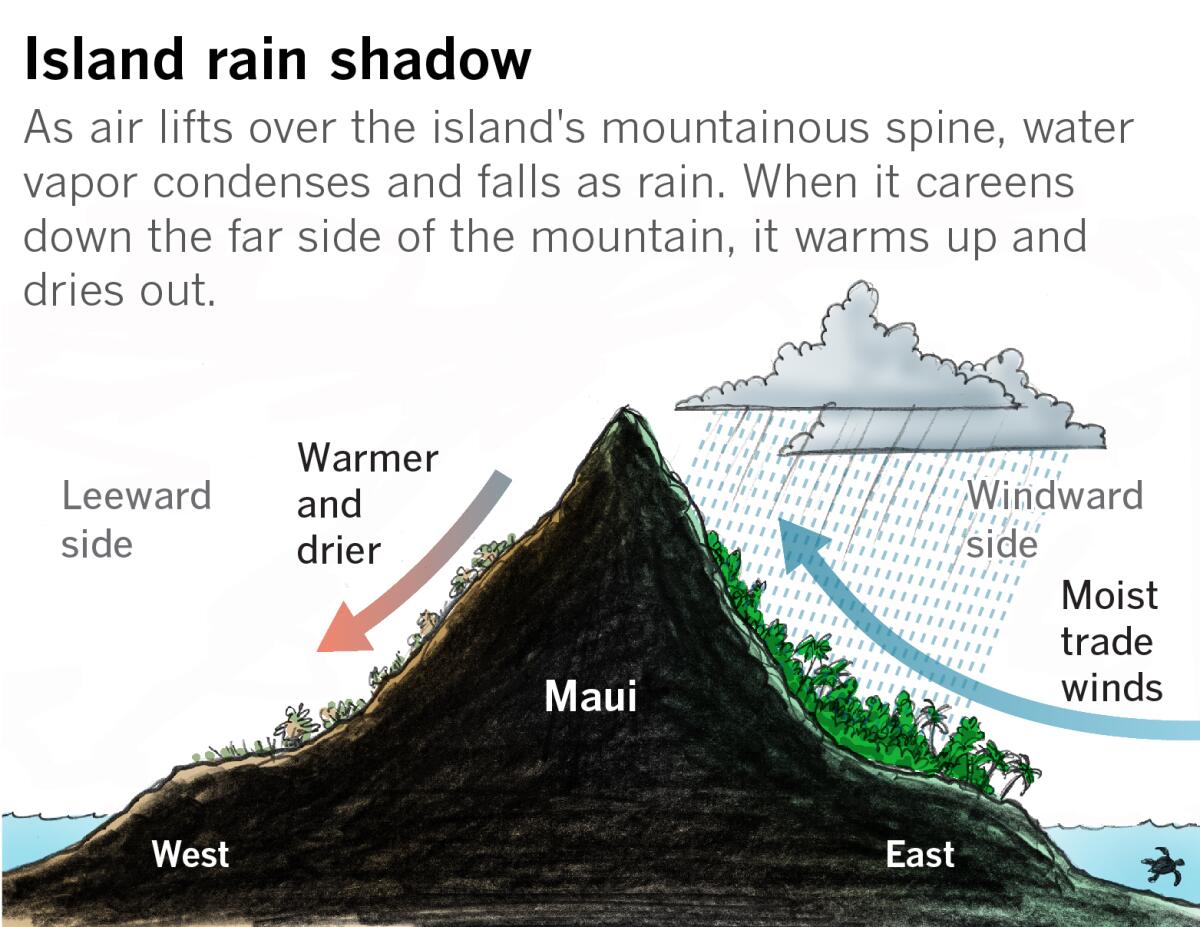

Areas in “severe drought” include Maui’s leeward side — where the now burned town of Lahaina is — while the windward side is considered “abnormally dry.”

“A lack of humidity and a lack of moisture is what you need in order to get a place like Hawaii to experience drought conditions,” said Samantha Stevenson, associate professor at the Bren School of Environmental Sciences & Management at UC Santa Barbara.

Maui’s terrain and prevailing wind patterns also had a powerful effect on the fire’s movement.

Although winds generally blow west to east along California’s coast, the opposite happens in Hawaii. On islands such as Maui, where a volcanic spine runs down the middle of the island, the eastern flanks are generally moist and lush — while the western slopes are in a rain shadow and typically drier.

“That means that the ecosystems on western slopes are often brushy scrubland more than lush forests,” said Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at UCLA. “And so the fires that we’re seeing are on the dry side — on the leeward side of the islands — where there is a lot of dry brush this time of year. … Also, it is unusually dry and warm, even for the dry season, right now.

But it’s the wind that turned the blaze into a firestorm, he said.

On Monday morning, winds from a passing Category 4 hurricane — 300 miles to the south of Maui — and a high-pressure system to the north, collided to generate gusts of up to 80 mph along the dry slopes of the island.

Hurricane Dora wasn’t close enough to deliver meaningful precipitation, but it helped amplify downslope winds that dried the air mass — not unlike what happens during a Santa Ana windstorm or sundowner event in California, Swain said.

Wind-whipped wildfires raced through the heart of the island of Maui, killing 53 people, forcing evacuations and gutting much of the historic town of Lahaina.

And although no scientist is likely to point to any one storm and suggest climate change is responsible for its generation, there’s been a steady uptick in the number of cyclones passing through the Central Pacific over the last 40 years, said Hiroyuki Murakami, a project scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory.

His work shows climate change is having an overall effect on both the frequency and intensity of cyclones across the globe.

Murakami said cool waters around the Hawaiian Islands had historically dissipated incoming cyclones — providing a natural barrier against these devastating storms. But warmer ocean waters caused by climate change and a burgeoning El Niño probably helped fuel the 4,300-mile trek that took Hurricane Dora from the waters off Mexico to the Central Pacific.

“That is an exceptionally lengthy trip for a Pacific cyclone,” Murakami said.

Fires across Maui have destroyed buildings and lead to at least six deaths. Photos from space show the scale of the destruction.

In addition to the winds and drought-like conditions, the humidity that morning was also exceptionally low — below 45%, said Ian Morrison, a meteorologist at the National Weather Service in Honolulu.

Indeed, although drought and wind can individually make fires more likely to ignite and spread quickly, “if you have them both together, it’s even worse,” said James Urban, an assistant professor in the department of fire protection engineering at Worcester Polytechnic Institute in Massachusetts.

When a blaze spreads from drought-dried vegetation into communities, it can become a different beast altogether.

Once a fire gets ahold of homes and structures, it can jump quickly from house to house, Urban said — particularly when strong winds send firebrands and embers aloft. He noted that some material inside homes such as furniture, clothes and insulation can also be highly flammable.

“If it started as a wildfire and then spread into the community, that transition could rapidly change the dynamics of the fire, and would be indicative of a pretty high-intensity wildfire,” Urban said.

Floods, fires, extreme heat, awful air quality, warming seas: As extreme weather engulfs the nation, the United States resembles a disaster movie set.

Abby Frazier, an assistant professor of geography at Clark University in Worcester, Mass., who earned postgraduate degrees at the University of Hawaii and has conducted research in the state, described a perfect storm of hurricane-fueled winds and dry conditions that contributed to the deadly blaze.

Land-use changes and the presence of non-native grasses also played a role in the conflagration. Maui does experience regular wildfires, and invasive grasses often sprout in their wake, Frazier said.

“If those aren’t managed very well, then we have a situation where you have lots of land area that’s primed to burn, unfortunately,” she said.

She also noted that Hawaii has a legacy of plantation agriculture, where land was managed for sugarcane, pineapple and other crops. But recent declines in farming have left many areas unmanaged and overgrown — brimming with even more invasive grasses and other flammable vegetation.

Improved forest management practices such as prescribed burns and fuel breaks could help mitigate some fire activity.

Record heat. Raging fires. What are the solutions?

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter about climate change, the environment and building a more sustainable California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

But, like Murakami, Frazier said that although it’s tempting to ascribe the current inferno to the worst effects of global warming, she cautioned that it is difficult to isolate the fingerprint of climate change on this particular event.

“We’ve seen century-long trends in drought across Hawaii — that droughts have been getting more severe and lasting longer, but it’s really difficult to actually put a climate change signal on that,” she said.

“I’m sure [climate change] is there in some level with the higher temperatures, but in terms of the precipitation variability and the land use, I think those are bigger factors in this particular fire.”

Frazier, who departed from Oahu shortly after the blaze ignited, said it has been terrible to witness the damage and rising death toll from afar.

“I really hope that people are OK,” she said. “I’m terrified to see the final aftermath and what things look like. It’s such a beautiful part of the state, and it’s absolutely devastating to see it like this.”