- Share via

HANFORD — As dark clouds massed over Kings County on the chilly morning of March 18, scores of panicked farmers and landowners packed the Board of Supervisors chambers in Hanford for a third day of emergency hearings. They were there to hurl accusations and blame and to plead with county leaders to do something to divert the floodwaters that were submerging their fields and homes, sapping their livelihoods and now threatening to wipe out the city of Corcoran and farm towns across the region.

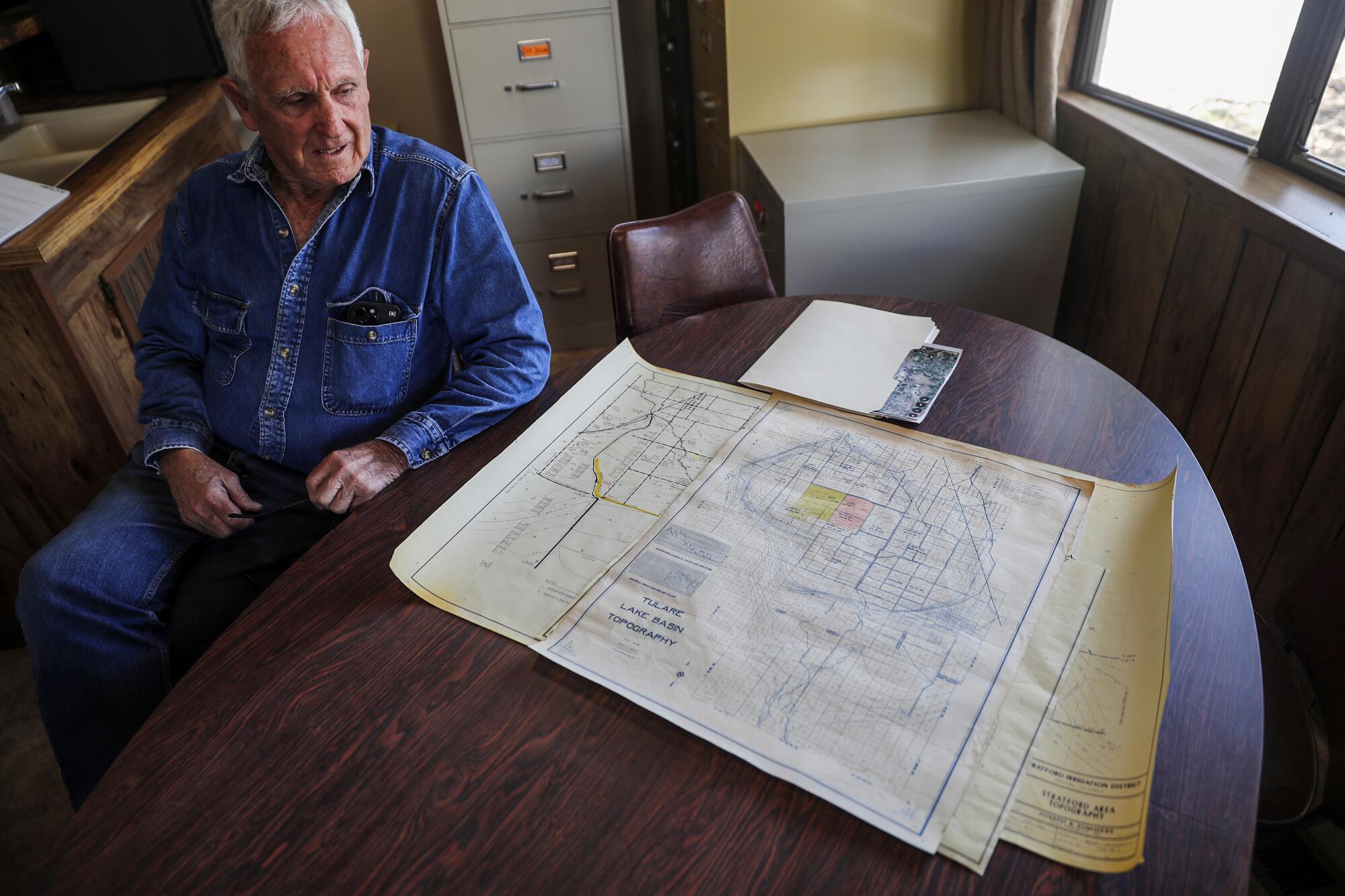

One by one, agitated farmers stood to address the supervisors. They pointed at maps and diagrams to show areas of the Tulare Lake Basin that had been inundated in past floods that now were dry, and areas that had never flooded but were now underwater.

They didn’t understand what was happening with the floodwater — and why it seemed to be coursing onto farms and ranches where it had never gone before.

“We’ve lost control,” one farmer shouted in exasperation.

For three months, storms had pounded California, and rivers in the southern San Joaquin Valley were overflowing. Levees were breaching. Tulare Lake, an ancient inland sea drained a century ago in the service of agribusiness, had reemerged with a vengeance in the valley’s lowlands, swallowing vast acres of farmland. Chickens were drowning at industrial-scale poultry farms, and dairies were evacuating thousands of cows.

As the lake grew deeper and wider, some landowners in the basin embarked on a mad rush to protect their interests. One levee was cut in the dead of night, sending water rushing toward the small town of Allensworth. Private security forces roamed the tops of berms to prevent anyone else from acting on a similar idea.

Aggressive and impactful reporting on climate change, the environment, health and science.

At one point in the hearing, brothers Phil and Erik Hansen, fifth-generation farmers in Kings County, voiced a brewing suspicion: J.G. Boswell Co., the tomato- and cotton-growing giant whose namesake family had wielded outsized power in the region for nearly a century, was brazenly rigging conditions to spare its own property in the lowest reaches of the lakebed.

It was a sentiment several local officials and landowners had expressed only in private, for fear of drawing the company’s wrath: that instead of letting the floodwaters take their natural course onto Boswell acreage in the lowest areas of the old Tulare lakebed, the company had raised levees and engineered irrigation canals to send the water surging onto farms and ranches on higher ground.

Cotton fields and homes the Hansens owned on the southeast side of the lakebed that had never flooded were now submerged — devastation they claimed occurred because Boswell had sent water rushing onto their land.

“It was premeditated,” Erik Hansen told the crowd. “They knew it would break on us.”

Boswell representatives acknowledged at the hearing that they had an interest in protecting the company’s crops and infrastructure. But they maintained their top priority was protecting Corcoran and said they were managing the floodwaters on their land to that end. Others in the room pushed back, saying Corcoran remained at grave risk.

At the end of the contentious hearing, Kings County supervisors took an action never before taken in county history. They voted to cut a levee on farmland owned by Boswell to buy time for Corcoran, home to 20,000 people and one of California’s largest maximum security prisons, as the town scrambled to raise earthen defenses against the encroaching floodwaters.

The decision was met with incredulity and fury by the powerhouse farming company.

“Boswell has been farming in the Corcoran area since 1925. Ninety-eight years,” George Wurzel, Boswell’s president and chief operating officer, told the supervisors. “And in 98 years, the county supervisors have never gotten involved in telling us where to put floodwater.”

In most parts of California, and indeed the United States, the idea that the government would largely cede to private companies management of a natural disaster that could decimate multiple towns, displace thousands of farmworkers and wreak destruction across hundreds of square miles would be unfathomable.

But that has long been how things operate in the Tulare Lake Basin. Land barons, chief among them J.G. Boswell’s founder, seized control of the basin and its water generations ago and have since managed it with minimal government interference.

In recent months, a team from The Times interviewed dozens of farmers, residents, government officials and policy experts; reviewed property records, court filings, water district records and historical documents; and spent hours driving around and flying over the lakebed.

The picture that emerged is one of a region that operates more like a secretive fiefdom ruled by a handful of legacy farming clans than a publicly governed jurisdiction where decisions affecting the well-being of residents are made on a foundation of transparency and accountability.

Among The Times’ findings:

The flood-prone Tulare Lake Basin is the one part of the Central Valley that has a special exemption from state-required flood control plans, leaving the area without a clear public strategy for managing floodwaters. State and federal flood maps offer scant information about the location or condition of the hundreds of miles of levees and canals in the basin — which spans portions of Kings and Tulare counties — because no one has ever reported it in detail.

And because the landscape is constantly in flux — as levees, berms and ditches are built, cut and rerouted as private landowners see fit — residents, lawmakers and water managers were unable to plan for and mitigate the damage as the floodwaters poured in.

The situation has been compounded by the unrestrained pumping of groundwater in recent decades. This is causing large swaths of the valley floor to sink, further changing the path water takes in the basin.

Local flood control and water conveyance districts, made up of powerful farming interests, make decisions about water infrastructure. Some refer to themselves as government entities; others receive tax-exempt status to store, divert and channel water.

Even the governor appeared flummoxed when he visited in April.

“It’s complicated,” Gov. Gavin Newsom said as he stood beside the newly formed Tulare Lake near Corcoran. He had come down after local officials begged the state for money to build up the Corcoran levee, a 14-mile-long earthen wall that protects the town and prison when water rises in the lake bottom.

But the region’s lawmakers had opted out of so many state programs, and officials had such scarce information about the region’s water dynamics, that figuring out how to provide aid was complicated. State officials, Newsom said, were trying to assess “exactly the rules of engagement.”

Six months later, they’re still trying to figure it out.

“I would observe that we have some big local landowners that say, ‘See, we managed this, and it went fine this year,’” said Karla Nemeth, director of California’s Department of Water Resources. “But there’s also a lot of folks in that region that came away from the spring saying, ‘We don’t understand what happened. We don’t understand who was making decisions, and we don’t understand what the plan is.”

This year, Corcoran and other towns in the Tulare Lake Basin were largely spared, in part because of decisions made by landowners and state and local officials — and in part just by pure luck as record snowpack in the southern Sierra Nevada melted more slowly than expected. But in the years to come, the potential for more record precipitation and drought — volatile weather swings unleashed by the changing climate — is likely to stress the system in ways that will make this past year seem benign.

While whole towns were not destroyed, this year’s flooding left clear winners and losers. The revived Tulare Lake could put some farmland and orchards out of circulation for years. The economic devastation is projected at roughly $1 billion.

“Are we going to be bankrupt? Are we going to be in business? I don’t know,“ said farmer Makram Hanna, whose pistachio orchard was flooded by a broken levee, leaving hundreds of acres of trees suffocating under 2 feet of water.

The episode has fractured some longtime relations in this lucrative corner of the San Joaquin Valley, and left troubling questions about the wet winters and dry summers to come: When water is overwhelming — or desperately scarce — who will suffer and who will thrive? And who gets to decide?

Before the rivers that once roared out the southern Sierra Nevada were diverted for agriculture, back when Tulare Lake was the center of life for the Native Yokut people, the lake could stretch for 790 square miles, four times the size of Lake Tahoe. The lake and its extensive wetlands once teemed with fish, birds, beavers and frogs, and the people who lived on its shores built rafts out of tules and fished with basket traps.

But even after the region’s four major rivers — the Kaweah, Tule, Kern and Kings — were diverted for irrigation and the lakebed carved up and cultivated, Tulare Lake returned in years of heavy rain. It came back in 1937, 1952, 1969, 1983 and, in much smaller form, in 1997.

More than a decade after California passed the Human Right to Water Act, about 1 million residents still lack access to clean, safe, affordable water.

This year, after the spate of intense winter storms and spring runoff from a record-high Sierra snowpack, the flooding was more intense than many old-timers could remember.

“I don’t even want to call it a lakebed,” Kings County Supervisor Richard Valle said in April after viewing the scene from the air. “I saw an ocean of water. I want to be clear about that: I saw an ocean.”

Each time the water returns, the biggest landowners get to work managing the flow. They maintain most of the irrigation canals and levees that weave through the lake bottom, dividing it into cells where water can be channeled and stored. They often have more extensive earth-moving equipment than the local governments — and are more skilled at using it.

During the second week of March, as it became clear Tulare Lake was rising once more, Boswell, the indisputable lord of the lakebed, got cracking. Company crews brought in a small army of earth-movers, trucks and bulldozers and started rearranging earth.

Boswell family members and company officials have a long history of refusing to talk to the media, and declined numerous requests from The Times for comment. But local government officials and fellow farmers in the basin shared their observations of what unfolded.

In years past, there has been an established order for how to handle the periodic episodes when floodwaters cascaded into the basin: Water would be allowed to flow where gravity took it, to the deepest section of the lakebed, before being allowed to encroach on higher ground.

“You can’t fill a bucket from the top down,” Jim Verboon, descendant of another legacy farming clan, said at the March 18 supervisors meeting.

About 44% of the lakebed — more than 97,000 acres — belongs to the Boswell company. And this year, said experts and fellow farmers, the company took a starkly different approach to letting its bottom lands flood.

Across the lake bottom, Boswell had bolstered its levee system to direct the water, while keeping expansive stretches of the company land protected and dry.

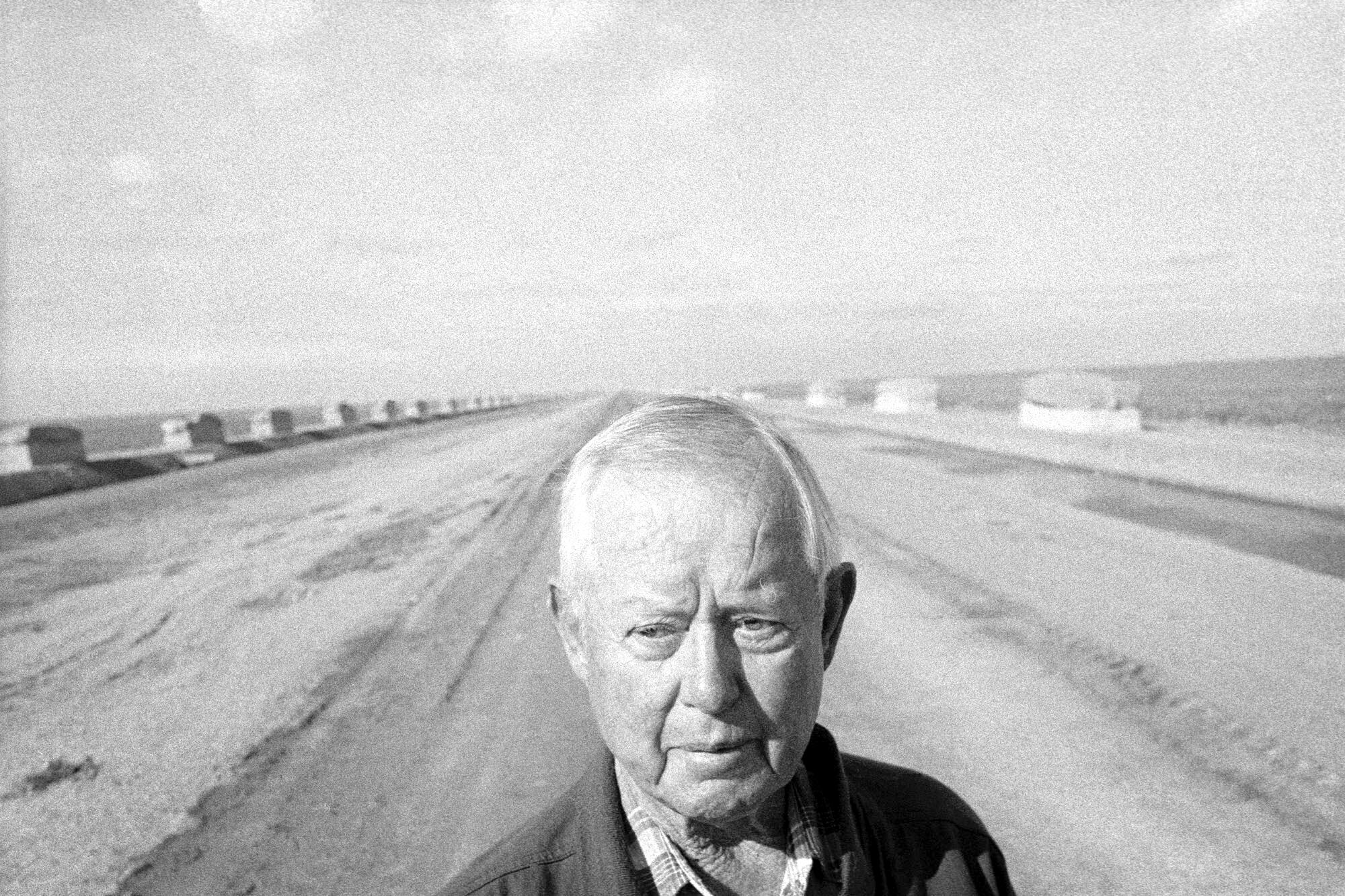

“This was all underwater in ‘83,” Mark Grewal said during a truck tour of the basin in early May. “All that water should have been contained here and it shouldn’t be near Corcoran.”

Grewal was a manager at Boswell for 26 years and is deeply familiar with company operations and basin history. He now works as an independent agricultural consultant for other growers, and said this year’s response to the flooding — and the resulting devastation — was unlike anything he’d witnessed.

Grewal stopped his pickup along a raised road that cut through Boswell property in the lakebed bottom. Small tomato plants sprouted in tidy rows on one side of the road and pima cotton on the other.

In the distance, a Boswell crew with earth-movers was building a levee, a rising barrier of mounded dirt. “That’s their new battle wall,” Grewal said. “They’re going to go ahead and plant their crops from that point south.”

“They might have all the rights to do what they’re doing,” Grewal added. But “because something’s legal doesn’t make it right.”

He said in previous floods, this area — in Delta Lands Reclamation District 770 — was the first to be flooded. Local reclamation districts, many of them controlled by Boswell, worked to contain floodwater to the fewest acres possible, to minimize crop losses and dampen the economic hit to the broader community.

That requires directing water to the deepest areas of the lakebed. In past floods, Boswell made strategic cuts in its levees to allow certain sectors of its cropland to be flooded and then held off planting those fields until the water receded.

That didn’t happen in the same way this time.

Instead, Grewal and others said, water flowed toward the east and north. The result was wide-scale inundation on farms and ranches that had not flooded in the past. Much of that land is planted with permanent crops, such as pistachios and almonds, which amplified losses in the region, Grewal said.

“There’s a lot of money at stake here, and they want to protect their crop,” Grewal said of Boswell’s tactics. “They don’t want to take the hit. So somebody else will.”

Grewal said his issue was not just with the Boswell response. In general, he said, the floods were being handled differently than in the past, including the county’s unprecedented involvement. The combination, he said, had put Corcoran in serious danger — and now the city was asking for millions of dollars in public funding to shore up defenses.

Similar accusations against Boswell had been lodged weeks earlier by growers at the March 18 meeting: that the company was either sending water onto other farms and ranches on higher ground, or altering infrastructure to change historical flows.

Elsewhere in the state, disaster response officials have detailed maps of levee systems and roads that help them strategize flood management. Using advanced satellite and mapping capabilities, they know the elevations of fields, ditches, berms and even the contours of ancient lakebeds.

One of America’s reddest states is seeking 100% clean energy. But does hydropower count as clean?

But as the flooding happened in March, the only maps readily available were ones created by the Boswell company.

Corcoran City Manager Greg Gatzka said he turned to the state Department of Water Resources for guidance when it first became clear the city was at risk of catastrophic flooding.

“Their assessment to us was, ‘Hey, we don’t have enough information. ... This is a black hole of data to us,’ ” Gatzka recalled.

But it wasn’t a black hole to the Boswell company. Officials there, Gatzka said, had “critical information” about where water was flowing and when. “Their watermasters, their water engineers and hydrologists were giving us updates,” he said. “It was a game changer.”

It’s also what led to the distrust and confusion.

According to the Boswell map, the Hansens’ land was in an area of the basin called the Southeast Lakebed. It was depicted as one of the lowest-elevation areas in the region.

“That Southeast Lake area right there? That’s made up,” Phil Hansen told supervisors at the March hearing as he pointed to the Boswell map. “That area has never been in the lake bottom. It’s never flooded before.”

Boswell representatives contended that subsidence of the valley floor and other infrastructure projects in the region had changed the way water flowed. But without maps or information from a neutral party, the supervisors seemed skeptical.

“I met with an expert and someone who worked the last two floods,” Valle told the audience. “And almost every question that I asked, his answer was opposite of what I was told by Boswell.”

As the crisis mounted, the company’s unusual clout in the basin played out in other remarkable ways.

At the southwest edge of the lakebed, the Los Angeles County Sanitation District owns 14,600 acres of farmland. Roughly eight times a day, a truckload of sewage sludge, processed in part from human waste, is dropped at the site and converted to compost.

After news stories suggested the composting facility could flood and sewage could contaminate basin acreage planted with food crops, nearby farmers, including Boswell, “became concerned,” said Doug Verboon, a Kings County supervisor and fourth-generation farmer. He said he put the sanitation district and Boswell in touch to exchange information.

Within days, the Boswell company brought earth-moving equipment onto the county’s property and dug two canals, according to officials from the sanitation district.

The purpose of the canals was to help Boswell move water off its lands to the east, said district officials. Whether it also was meant to prevent sewage sludge from infiltrating farms is unclear, because little was done to document it.

The work was all done without a contract. When The Times asked the sanitation district for documentation on the construction project — who paid for the canals, who is responsible for upkeep — officials said there wasn’t any. A public records request also came up empty.

“I think, you know, in terms of what we would normally do — in terms of how we’d ordinarily have a really rigorous, like an agreement structure in [place] and those kinds of things — because it was an emergency, we don’t have all those bells and whistles,” said Ajay Malik, head of the county sewage district’s technical services department.

Malik was referring to an executive order signed by the governor on March 31 that waived “certain statutes and regulations to expedite emergency flood preparation” in the Tulare Lake Basin.

Mike Sullivan, assistant head of the technical services department, drove a Times team around the county site in June. Slicing two miles east to west across the property, fresh earth from a deep cut in the fields was pushed up along the perimeter of a 10-to-12-foot-wide canal. To the east, water could be seen gushing out of a handful of pumps located on flooded Boswell property and into the newly cut canals on the district property. A similar canal was dug at the southern edge of the property.

When asked why the Boswell company was pumping water into the canals and where it was going, Sullivan said he did not know.

Asked who owned the canals built on county land, Malik said it was a “good question.”

“I think you make a very good point about ownership,” he said. “I think that’s a very critical thing and who’s responsible for maintaining them or operating them? I think these are all excellent questions to ask. We’re going to go and sit down with the Boswell representatives and decide on all of these things.”

James Griffin Boswell, the company’s founder and the scion of a cotton family in Georgia, arrived in California in 1921. He jumped into the cultivation business, joining forces with other pioneer families to re-engineer the Tulare lakebed into an agricultural powerhouse.

As Mark Arax and Rick Wartzman recounted in “The King of California,” their 2003 book about Boswell and his nephew and successor, James G. Boswell II: “No longer content with simply siphoning water from the Kings, Tule and Kaweah, farmers began altering the very bend of the rivers, turning meanders into lines as perfect as a draftsman’s.” The end result was so incredible, they noted, that Tulare Lake turned up in “Ripley’s Believe It or Not” as the “Square Lake.”

“No landscape in America — not the cotton South, not the grain belt of the Midwest, not the cane fields of Florida — had been more altered by the hand of agriculture,” Arax and Wartzman wrote.

Boswell eventually married Ruth Chandler, daughter of The Times’ then-publisher, land baron Harry Chandler, and quietly carved out one of the richest cotton empires in the nation. Boswell II inherited the business when his uncle died in 1952 and over time tripled the size of the company’s holdings, which now encompass more than 150,000 acres across the San Joaquin Valley.

The company scored a critical coup in that journey in 1954. Pressed by Boswell II and other Tulare basin farmers, the federal government finished construction of the Pine Flat Dam on the Kings River, followed in the 1960s by dams on the Kaweah and Tule rivers. The dams limited flooding in the lakebed in wet winters and guaranteed the farmers a steady supply of water in the San Joaquin Valley’s long arid summers.

While the Boswells were the largest landowners, the basin had other legacy families that accumulated power along with land. Among them: the Gilkeys, the Hansens and the Boyetts.

Through heavy lobbying and fancy legal footwork, the Boswells and other barons prevailed upon the government to exempt them from federal reclamation laws that were supposed to ensure that cheap federal water went only to small farmers. The big farmers consolidated their power by creating flood control and irrigation districts — government agencies whose boards are largely run by the farmers or their representatives. The farmers also created tax-exempt organizations to manage their water rights.

Ron Stork, a senior staff member for the environmental group Friends of the River, noted that in other flood-prone regions of the state, flood protection boards, counties and the Army Corps of Engineers have authority over levees and the flow of water. But in the Tulare basin, Stork said, the accepted practice has long been for farmers to simply do “what they can to protect their land and farming operations.”

Because of local opposition, the Tulare basin was exempted from 2008 legislation that led to the development of the state’s Central Valley Flood Protection Plan, which guides strategies in managing flood risks. Left out of this blueprint, the Tulare basin remains a zone with minimal state involvement and little public planning for flood control, even though its low-lying location puts towns and farmland at risk.

“I think the challenge in the Tulare basin is, when the flood planning is managed so extensively by individuals, significant landowners, who does a community call when they sense a flood threat?” said Nemeth, director of the state’s water department. “Are they calling a big landowner to say, you know, ‘Tell us what’s happening, tell us what we need to do to be safe.’ ”

Tulare Lake’s rebirth will reshape life in the San Joaquin Valley for years to come. But longtime residents remain committed to the region and its remarkable seasonal rhythms.

The large number of water-related districts and special entities adds to the confusion. The Times identified more than two dozen flood control and irrigation districts and tax-exempt water purveyors in the Tulare basin, although the exact number was difficult to come by. Not every organization has a website or a clear way for the public to identify its scope and membership.

Of the 25 districts and canal companies The Times identified, representatives from the Boswell company serve on the board of at least 17.

Michael Kiparsky, founding director of the Wheeler Water Institute at UC Berkeley’s School of Law, studies such districts across the western United States and noted that they often operate with “all the shadowiness of a privately held corporation and all the power of a public entity.”

A case in point: The Cross Creek Flood Control District, which maintains the 14 miles of levees protecting the city of Corcoran, has a landing page on the county website but no information, not even a phone number.

Kiparsky said the idea behind creating these quasi-governmental districts was sound. They brought together a group of landowners and enabled them to pool resources and build costly water infrastructure.

The problem, he said, is that you can “get situations where you literally have one or a small number of very large landowners controlling an entity that is managing a public resource owned by the state of California.”

In dry years, the farmers’ control over the water has been a source of outrage to some who question why such a vital public resource — water — should be presided over by so few.

But in wet years, when the lake comes roaring back, the fight isn’t about who should get the most water. It is about who will get drowned.

Over the years, many private landowners have built levees and berms to protect their investments. In May, a privately built levee on farmland near Corcoran broke and water rushed onto a neighboring orchard planted with hundreds of acres of pistachio trees.

Hanna, who owns the 1,270-acre orchard together with relatives and two other families, had planted the trees in 2021. About 800 acres were inundated.

Hanna fumed about how one of his neighbors responded to the flooding. After the neighbor harvested his wheat, Hanna said, that farmer built a berm that prevented water from flowing onto his empty field, which kept water on a portion of Hanna’s orchard.

Reached by The Times, the neighbor declined to comment.

That section eventually dried out, but tens of thousands of trees elsewhere in Hanna’s orchard remained underwater through the summer, while workers ran pumps to siphon it off. When the floodwaters finally receded, many of his trees had been reduced to withered sticks. Hanna estimates the farm will be left with about half the trees it once had. Ultimately, he paid a contractor $92,000 to haul truckloads of dirt, about 300 loads, to plug the broken levee.

Looking back on the flooding, Hanna said he was deeply grateful to one neighbor, Kirk Gilkey, who sent a crew to build a mound to keep water off part of Hanna’s land.

“Good people come to aid,” Hanna said. “Selfish people think about themselves.”

Fifteen miles west, farmer Charlie Meyer commended neighbors helping neighbors but said the free-for-all illustrates why the government should play a stronger role in managing levees during floods.

Meyer is 83, and has spent his life in Stratford, where his family farms 1,100 acres of cotton, pistachios, alfalfa and hemp. Small farmers on the lakebed’s edge, he said, have long operated at the whim of lake bottom farmers and their ability to channel water where they see fit on their massive holdings.

To make his point, he took a reporter up in his plane in May. As the four-seater Cessna climbed from the airstrip behind Meyer’s home, roofs of submerged dairy and poultry farms jutted out from underneath the seeming ocean of grayish-blue water.

In 1969, Meyer said, water came close to his house. But it was shallow, and it took only a week to pump it dry. This time was different, he said, in part because the big farmers raised levees that stopped the water from moving south and flooding areas that historically had filled.

“There’s no justice,” Meyer said. “There’s only political clout.”

No matter which side of the levee they stand on, almost everyone in the Tulare Lake Basin agrees that the damage has been more far-reaching than in years past.

One factor was the sheer intensity of the storms that moved through the basin.

Another is that growers such as Hanna have planted so many more permanent crops in and near the lake bottom. That makes the losses much costlier. Forgoing a seasonal cotton crop for a year or two is one thing; the loss of thousands of nut trees to root rot is quite another.

In addition, there are the shifting contours of the San Joaquin Valley floor due to excessive groundwater pumping. Over the last two decades, farmers have pumped so much water from the aquifer beneath the Tulare basin that the land has sunk. In some areas of the basin, especially to the north and east, the land has sunk by 3 to 6 feet since 2015, according to recent satellite data.

The consequences of that were evident when this year’s flooding began. Buildings — including homes and dairies full of cows — that had never flooded before and that their owners assumed were safely constructed began to take on water.

“I never thought it would come,” said Anja Raudabaugh, president of the Western Dairies Assn., after hearing from dairy owner after dairy owner that their structures were inundated.

“They knew they were farming in a floodplain and tried to mitigate by maybe building their barn, you know, 4 or 5 feet higher in elevation,” she said. “It’s like Poseidon’s hand has literally covered Tulare and Kings counties.”

The subsidence cannot be laid at the feet of any one farmer. Through years of drought, almost anyone with a drill and well pumped as much water as they could. But many locals, including Supervisor Verboon, say two of the basin’s most powerful landowners bear much of the responsibility.

One of them is the Boswell company, which since 2009 has been led by Boswell II’s son, James W. Boswell. As the area’s largest groundwater pumper, the company has caused a substantial share of the subsidence.

Another is Sandridge Partners, a company controlled by the family of Silicon Valley multimillionaire John Vidovich. Vidovich is heir to De Anza Properties, a real estate enterprise founded by his father that was instrumental in turning the Santa Clara Valley into a commercial metropolis.

Over the years, Vidovich has generated resentment in the basin because of a history of buying land and selling some of its water outside the valley.

He and Boswell have had nasty public disputes involving water, as chronicled by reporter Lois Henry on her news site SJV Water. A Boswell-controlled company has sued to keep Sandridge from constructing a large pipeline to move water around the county, while Vidovich has openly challenged Boswell over the company’s practice of pumping up groundwater and storing it in ponds for later use.

Verboon contends enmity between Vidovich and Boswell made the flooding worse this year. He said that Vidovich could have used pumps to take water onto his land, but that he didn’t want to take it “until Boswell is flooded out first.”

“Each one wants to see the other fail,” Verboon said.

In an interview, Vidovich said, “I don’t have tensions with the Boswells.” He said that subsidence played a major role in this year’s flooding, and that he has suffered major losses because water conveyance systems are sinking. He wants limitations put in place to force significant reductions in groundwater pumping in the region.

“What went downhill is now going uphill,” he said. “We used to go by gravity, and now we have to put in many pumps to bring it back.”

As the water poured down in March, rushing into unexpected places, the Kings County supervisors felt they had no choice but to get involved.

On the morning of March 17, the board voted to cut Levee 749 in hopes of protecting Corcoran — only to stay their decision when the Boswell company objected.

Two board members, Verboon and Valle, drove to Corcoran that afternoon to meet with company representatives. “My daughter took photos because she thought they were gonna kill me,” Verboon said.

In the end, they agreed Boswell could make its case to the board the following day.

The meeting was as contentious as anyone in Kings County could remember.

Boswell officials gave a presentation laying out why they had sent water flowing to the southeast part of the lakebed. They argued that keeping space in the bottom of the lakebed was the best way to protect Corcoran from the threat of future flooding posed by the massive Sierra snowpack looming to the east.

But other farmers rejected the rationale, saying to prevent the threat of imminent flooding near Corcoran a Boswell levee had to be cut.

“What it does is buy you time,” said Jim Verboon, the supervisor’s cousin. “Right now we’re not doing a very good job of managing it to keep people that are upstream safe.”

In the face of such arguments, the supervisors held firm and upheld their vote to cut the Boswell levee. The cut was made that afternoon, with two sheriff’s deputies looking on.

Kirk Gilkey, 65, watched the fight between the Hansens and the Boswells and did his best to stay out of it. Gilkey descends from a family that bought into the lake bottom more than 100 years ago and owns more than 8,000 acres. By mid-April, he had lost 2,300 acres and was expecting to lose thousands more. It would be the first time in 75 years, he said, that his family did not grow cotton.

Members of the Gilkey family have, over the years, served on Corcoran’s chamber of commerce and city council and on the boards of water management districts that control where water flows in the basin and when. Gilkeys have walked as grand marshal in town parades and been crowned queen of the cotton festival.

But over and again this spring, Gilkey insisted that he wanted to stay out of the political and landowner disputes swirling around the flooding. It was a vow he stuck to through an hours-long tour of the flood-ravaged basin in his truck and over drinks at the Lake Bottom, Corcoran’s most popular bar.

The only time he broke that vow was when the issue of greater county or state regulation of Tulare basin was raised.

“Should there be more regulation? Hell no,” Gilkey said.

The Kings County supervisors, he said, have “got no clue.” And as for the state officials: “They don’t know what they’re doing.”

Tulare Lake is vast and inviting, but is it safe? We took a boat tour to find out what lies beneath its shimmering surface.

Given such sentiments and the region’s deference to its land barons, it’s difficult to say whether the supervisors’ decision to defy Boswell has any long-standing implications for water management in the Tulare Lake Basin.

Earlier this month, Verboon and the other supervisors quietly accepted two Boswell donations totaling $60,000. Both were intended for the county Sheriff’s Office, including a $50,000 gift for the sheriff’s “outstanding leadership during the recent floods.”

But the chaotic spring — and just how close the basin came to far-reaching disaster — has lit a simmering call for change.

It’s time for the basin to move on from “the Wild West,” said Deirdre Des Jardins, director of California Water Research, which analyzes how climate change will affect the state’s water infrastructure. “It’s insane to have a bunch of desperate farmers out there with backhoes, ignoring the liability of what might happen if they accidentally make things worse. We need a rational flood control plan and sustained long-term investment.”

Nemeth has come away thinking something has to change.

“And that’s where I would tell some of the bigger landowners, ‘Yeah, you managed it successfully this year. But you got this big temperature assist from Mother Nature,’ ” she said.

“And the public doesn’t know what it was and what to do and who made decisions.”

Nemeth said that as climate change rocks California, the Tulare basin needs to develop the same kind of regional flood planning in place in the rest of the Central Valley, and that it likely will take an act of the Legislature to make that happen.

“And again, it’s not about going in and directing what should happen. I want to be really clear about that,” she said. “But the state can’t be left completely holding the bag when there are gaps in that flood planning.”

After the last big flood in 1983, it took about two years before all the water receded. Now that Tulare Lake has resurfaced, some have suggested it would make sense for local governments and the state to coordinate on buying land from farmers to create space for future flooding.

There are also those who see forces at work stronger than the Tulare basin landowners. The Yokut people who once thrived along Tulare Lake’s shores are calling on the state to let the lake live on in some form rather than once more draining it into submission.

“Let Mother Nature take its course,” said Leo Sisco, chairman of the Santa Rosa Rancheria Tachi Yokut Tribe. “I think there’s plenty of room for having that lake here.”

Times staff writer Hayley Smith contributed to this report.

More to Read

About this story

A perimeter for the Tulare lakebed was produced by the United States Geological Survey.