Ken Baumann’s secret life in books

- Share via

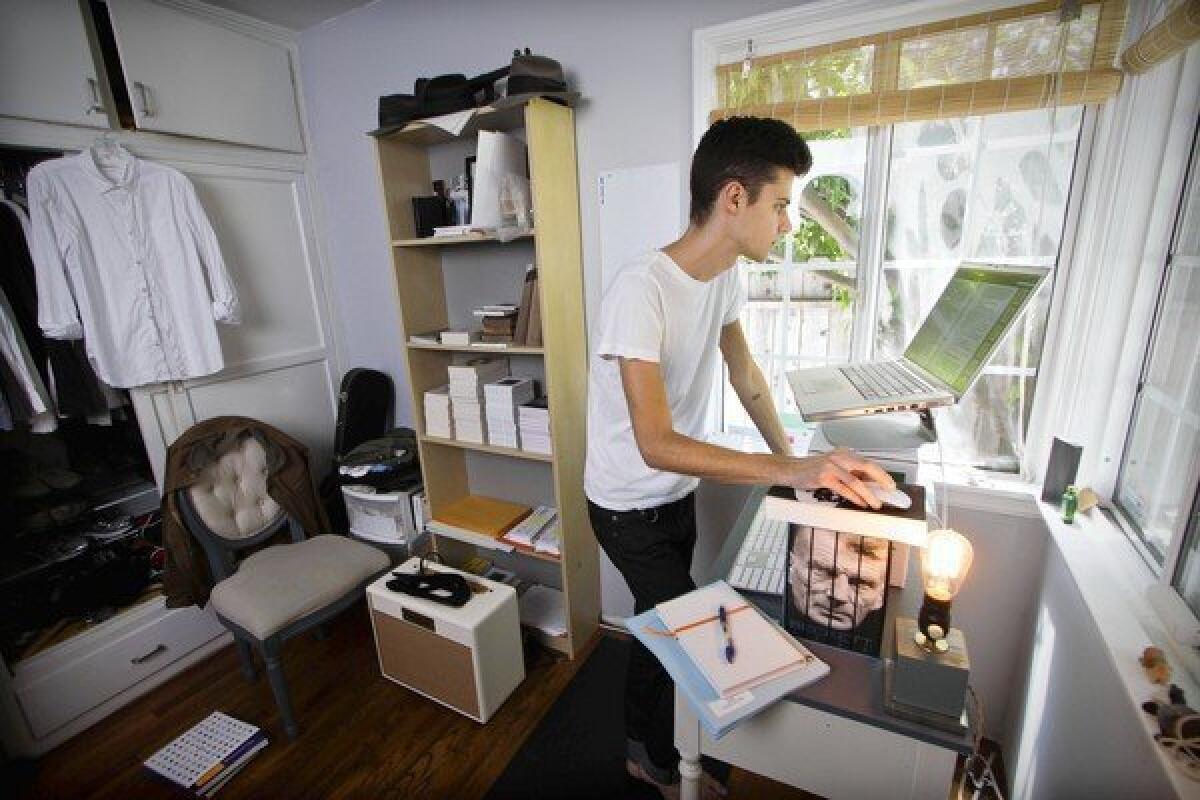

To some people — those who might attend a guerrilla reading in San Francisco, for example — Ken Baumann is a writer and small-press publisher who is part of the contemporary literary vanguard. And yet, to a generation of adolescent girls, he’s instantly recognizable as a star of the beloved ABC Family series “The Secret Life of the American Teenager,” now in its last season.

“As long as I can do both, why wouldn’t I want to?” Baumann asks at an L.A. cafe. He’s lanky and pale-skinned, making it easy to see why he was cast as a high school student in 2008 (he’s now 23).

“I am supporting myself doing something I love, which is performing, and I’m doing it for a huge audience, and that feels great,” he says. “I get to use what that gives me — both time-wise and financially — to brew up my weird little witchcraft on the side.”

That’s how he describes his literary life, which includes Sator Press, the avant-garde small press he founded in 2010, as well as his own writing. His first novel, “Solip,” will be published May 14 by the underground press Tyrant Books.

“‘Solip’ is hard to describe,” Baumann says. “When I wrote it, it felt like a grotesque, weird voice that had to get out. I’m glad it’s out, and I think it does some really cool stuff.” It’s an edgy book, without the comforts of a third-person narrator explaining the setting or plot.

Instead, its narrator appeals to the reader as if to prove its existence, sometimes aggressively, sometimes playfully. “Can I go dumb if I refuse? Forget at all if I use? Talk not to stop ought. Rather bark. Sour tickling is confined: Base of the skull or summit of stem. It’s very peculiar!”

On the book’s cover, publisher Giancarlo DiTrapano describes it as a “non-novel, a vast detonation of language” and acknowledges a debt to Samuel Beckett. Beckett’s importance might be a given among certain PhD circles, but Baumann doesn’t have a PhD. He graduated from his charter high school at 15 and has never taken a college class.

“I had really terrible, beautiful examples in my mom and dad: Neither of them went to college,” he explains. “My dad was a brilliant engineer; now he builds race cars and tries to break land speed records. My mom is equally as brilliant, so I have these two autodidacts — staring me in the face. I thought, man, I’m already reading a lot, and trying to think critically.” There was no reason to detour from his acting career to head to a university; he’d given himself an education.

It began when he found a copy of “The Stranger” by Albert Camus in an airport bookstore at 14 or 15. “When I got home — this is the new, modern, Enlightenment — I Googled ‘existentialism,’” he says wryly.

His Web search led him to Tao Lin, the absurdist and sometimes controversial author of “Eeeee Eee Eeee.” Lin’s website was a magnet for like-minded creative writers, and Baumann threw himself into their online midst, reading, learning and building relationships online and offline. One summer, he traveled through Europe with the author Blake Butler, founder of the contrarian literary blog HTML Giant; together, they edit the zine No Colony.

Working on the zine gave Baumann the confidence — and experience in print and design — to found Sator Press. He took the name from “SATOR AREPO TENET OPERA ROTAS,” a Latin palindrome written in five lines that reads forward, backward, up and down. Its first appearance was on a Pompeian wall and has been found across Europe over centuries; its true meaning is lost. Baumann used his favorite translation — “The great sower Arapoe holds all works in his hands” and uses “holding great works” — as the tag line for his publishing house.

In Sator Press, he wanted to create the right print home for the kind of works he’d been reading online. “I knew that there was an abundance of texts floating around from authors who had trouble placing them in the larger ecosystem,” he says. He did his research into the real world of publishing, talking to veterans like Richard Nash, former publisher of Soft Skull.

Nash recalls: “As the doctors might say, he presented as a patient with exactly the condition I expected him to be in possession of — the disease known as I Want to Be an Indie Publisher.” Nash had no idea Baumann was an actor; he saw him simply as a book lover. “He’s the real deal. It’s not like buying a quirky pair of pants; you don’t do this sort of thing unless you’re really into it.”

Baumann founded Sator Press as a nonprofit. His goals are manageable — a book or so a year, and press runs that are modest but not insignificant; each book starts with 1,000 copies. His highest-profile author is the poet-slash-aphorist Mark Leidner, whose Sator Press book was 2012’s “The Angel in the Dream of Our Hangover.” Baumann is Sator’s only employee, serving as editor, publisher, operations manager and book designer.

Layout at Sator is a serious undertaking — where most books consist of text flowing down a page, Sator’s may not. In “The Complete Works of Marvin K. Mooney,” a novel by Christopher Higgs published in 2012, lines of text break and stutter like poetry.

“I’d say 80% of the pages are complete architecture. Almost every page is a beautiful sculpture,” Baumann says, paging through the book. “That said, it almost gave me an aneurysm, doing the interior layout.”

He’s joking, but he did have a genuine health scare last year, when an undiagnosed case of Crohn’s disease led to emergency surgery — just weeks before his scheduled marriage to actress Aviva (“Superbad”). “I’m in great health now,” he assured me in April by email. “The ironic pleasure of being really sick with an on-the-books disease is having one distinct thing to hate and fight against.”

Baumann has a bit of the pugilist’s approach to literary culture — as Nash describes it, “a little in your face, a little bit of extra grit in the teeth.” It’s a tradition that goes back to some of America’s most important publishers, like Grove Press, which challenged censors to publish James Joyce in the U.S.

“I read a very long article on Barney Rosset and early Grove, and I was just sold,” Baumann says. “I’ve found the more I do it that it’s the most rewarding thing I do: Produce other people’s work and not just focus on my own. It’s a great step away from the swamps of self.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.