How I learned to stop worrying and love my Asian Glow

- Share via

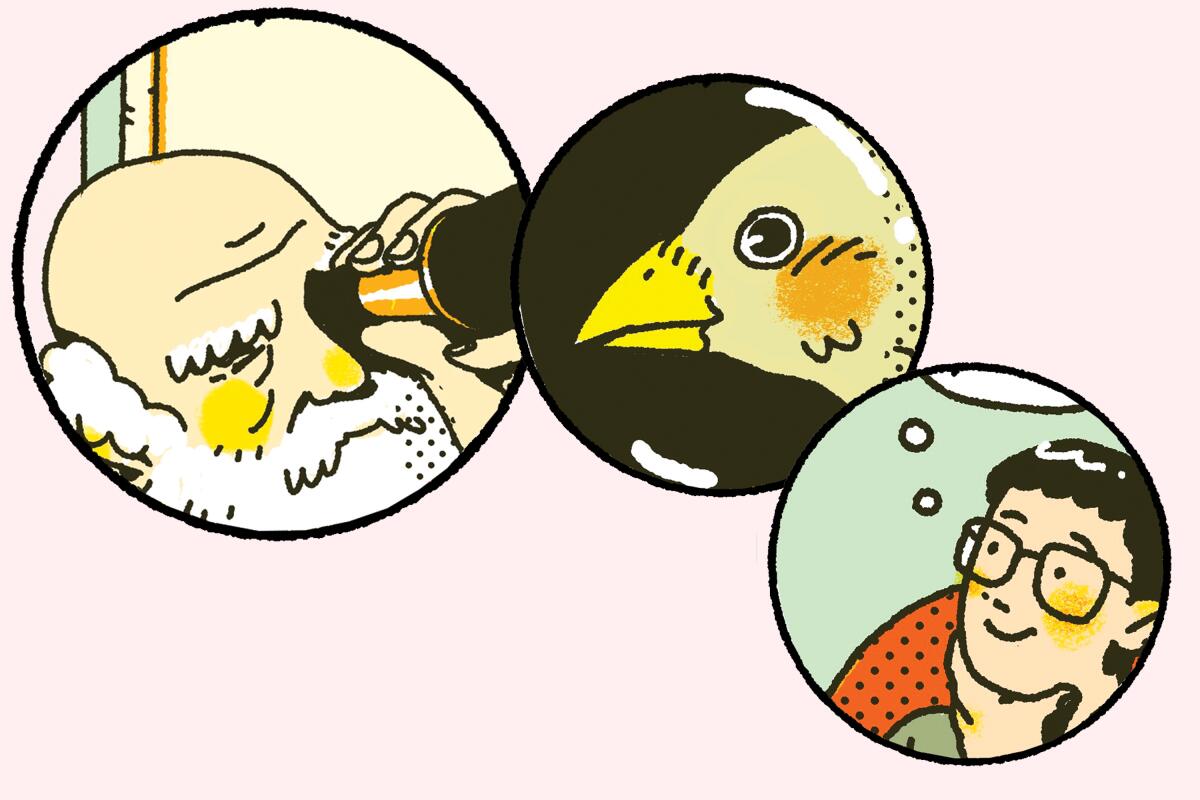

It starts almost immediately, within the first few sips. No more than a gentle warmth in the cheeks initially — like fogging a cold window with your breath, or the feeling of minor embarrassment, like getting caught talking to yourself in public.

But the sensation grows exponentially as I continue to drink an alcoholic beverage. And as the blood vessels in the face dilate, the heat spreads to the lobes of the ears, crawls up the scalp and slowly creeps down the neck.

My breathing becomes slightly labored and wheezy, as if a particularly dander-heavy cat has wandered into the room — a room that has puzzlingly begun to cant gently to one side, belying the single bottle of Bud Light on the bar that is most definitely still half full. My heart races, the skin around my eyes tightens, and the redness slowly permeates my rest of the body, like ink droplets in a glass of water.

My name is Lucas, and I have The Glow. The Asian Glow. It has taken me a long time to come to terms with it.

As a teenager, my inability to drink without turning into a crimson Violet Beauregarde tortured me. In my head it cost me friends, dating opportunities and a romantic, Hemingway-esque vision of myself sitting in an overstuffed armchair with a glass of Scotch writing lines like, “It was January. And it was cold. It was always cold.”

Because I turn bright red at the faintest whiff of alcohol, I felt like I was missing out on imagined nights of spontaneously getting blitzed and breaking into the high school’s pool, or making out with a cute stranger at a bar, or drunkenly stumbling home with a group of friends.

I wanted those memories — and felt robbed by my heredity. What other group of people is genetically predisposed to have an adverse reaction to Fun and Good Times?

Asian Glow, or alcohol flush reaction, is a perplexing genetic variation that affects almost exclusively persons of East Asian descent — a whopping 38% of us — and is the bane of many young adult lives.

This is basically how it works: It’s different from an allergy, which is an overreaction by the immune system to an irritant, like pollen or peanuts. When humans drink, the ALDH2 gene, located on chromosome 12, encodes an enzyme that breaks down acetaldehyde, a toxic byproduct of alcohol. That toxin, for whatever reason, triggers blood vessel dilation when it floods the body, which makes you turn red.

A lot of East Asians have a variant of the gene that underperforms. “If you have the variant, the process slows down,” explained Becca Krock, a product scientist at genetics company 23andMe. “It still produces the enzyme, but the enzyme doesn’t work as well.”

And what happens if you can’t metabolize that acetaldehyde? It triggers blood vessel dilation as it courses through the body, which makes you turn red. Lustrously, luminously red. And also maybe gives you a pulsing headache that comes with a side of slight nausea as well as an order of need-to-lie-down-for-a-second.

My imagined life as a debonair, free-wheeling drinker came to a screeching halt the first time I drank during a house party in mostly white suburban Chicago in high school. Someone had brought Zima. We listened to “Ill Communication.” And I drank the execrable fizzy malt beverage until a friend pointed at me and said, “Dude, what is wrong with your face? You’re like, bright red!”

In the bathroom, I examined my face, which was, indeed, bright red. But it was oddly nonuniform. My cheeks were glowing; my nose wasn’t. The area around my eyes was red; my mouth wasn’t. The skin that wasn’t red looked waxy and slightly green-ish, like that of a corpse. I already felt self-conscious about being the only Asian kid at every party I went to; this compounded it. Alcohol, the promised salve of every teenage woe, was doing the opposite of what it was supposed to do.

I spent my first couple of years at college trying to drink and failing. Once there was a deliberate attempt to get drunk with my roommate in which we sat on the floor alone and matched each other shot for shot with a bottle of Cuervo. (I wanted to know what drunkenness was and if it was the same thing as Asian Glow. It’s not.) During most of the others, I ended up calling it an early night after a cup of Milwaukee’s Best turned me into a splotchy lobster. On one or two rare occasions, for apparently no reason at all, I was totally unaffected.

In adulthood, my drinking life has largely been one big lie. Ordering beers with the lowest alcohol content. Drinking half then secretly dumping the rest into the bushes when no one is looking. Bringing drinks to the bathroom and dumping them into the toilet. Ordering soda and bitters at the bar and pretending I’m drinking a cocktail.

Why go through all this?

Because alcohol, the great social WD-40, is hard to eschew, especially in your teens and 20s, and especially if you care about having friends. A study led by a French doctor (naturally) found that men and women who regularly drank were happier — not for physiological reasons but because they had more active social lives.

It’s easier to play along rather than reject the friend offering you a drink, hand outstretched, and risk seeing a smile turn into a look of befuddlement. Who wants to risk the incredulous response to already-poured wine, the face that says, “Well, what do you want me to do? Pour it back into the bottle?” And no one who drinks — which feels a lot like everyone — likes the person who, at the end of a meal, wants to pay for what they ate but not what they didn’t imbibe.

I’ve tried every home remedy and apocryphal cure to counteract the Glow, never with any success. Tums. Hot showers. Eating a heavy meal beforehand. Claritin. Pepcid is a popular choice — I know a dozen people who swear by it — but it’s never worked for me. And it’s just as well; an antihistamine can block some of the effects of Asian Glow but doesn’t necessarily affect or improve the body’s ability to process alcohol.

It’s similar to people who have trouble breaking down lactose, Krock explained, in which the small intestine doesn’t produce enough of the enzyme lactase. But in the lactose-intolerant, there’s a dearth of the enzyme; in those who get Asian Glow, the enzyme is there, it just underperforms.

The irony is that many Asians continue to drink, hard, despite the discomfort associated with the drinking as well as the health risks, like an increased chance of esophageal cancer associated with this reaction to alcohol. Alcohol consumption rates in some Asian countries, like South Korea, are higher than in the United States.

In countries where drinking is thoroughly ingrained into male-dominated workspaces, it’s almost impossible to refuse. During a year of living in China, I went to at least a dozen parties and functions where I had baijiu, the paint-thinner-like spirit, foisted on me by friends, coworkers and superiors. One night, I was railroaded into playing a drinking game that involved a rock-paper-scissors-like strategy I didn’t quite grasp. (It involved smacking chopsticks on the table while yelling about sticks, tigers and worms, all of which trumped each other in various ways. Anyway, I lost.)

But there, at least, I had comrades in my redness and discomfort. “It does seem to be clear that this variant arose in southeast China,” Krock said. “It’s most common in this area and becomes less common the farther away you get.”

I’d always regarded my inability to drink as a disadvantage. But as I’ve aged, I’ve accepted the Glow. The social capital I missed out on I’ve saved in actual, legal tender by forgoing the 500 or so drinks per year consumed by the average American. I’m a cheap date; a few sips of wine or a bottle of 1-proof kombucha and I’m good to go for the evening. I’ve never gotten a DUI or said or done anything I’ve regretted due to having drunk too much.

And as time goes on, it’s gotten easier. Aging, which takes its toll in myriad other ways, grants at least one benefit: You stop caring as much what other people think. Rejecting alcohol is no longer as taxing. You also can’t party like you used to: Many of my friends have naturally cut back on their drinking, for personal or health reasons, rather than hereditary (and sometimes all three). And — less of a factor but still relevant — more restaurants are catering to nondrinkers. Nonalcoholic pairings at fancy restaurants are often more interesting than the wine program.

But why did this mutation evolve? And why in Asians? And, as my 22-year-old self frantically splashing cold water on his face in the bathroom in the middle of a date might ask, “Why me?”

There’s no definitive explanation. “It may have arisen in a time and place where people weren’t drinking much alcohol and it just happened to spread,” Krock said.

I’ve found my greatest peace with the Glow in, of all places, the words of Charles Darwin.

In 1835, during the second voyage of the H.M.S. Beagle, he documented more than a dozen species of finches that became essential to his theories of evolution and natural selection. The birds, he noted, had developed different-shaped beaks depending on their environments or what they ate on the Galápagos Islands.

These small genetic variations “will tend to the preservation of that individual, and will generally be inherited by its offspring. The offspring, also, will thus have a better chance of surviving,” Darwin wrote in “On the Origin of Species.”

That’s my hope: that we’re like those finches with the short, stubby beaks that were great for breaking seeds or maybe the ones with long, thin beaks that were handy for punching holes into the sides of cacti. That there’s a clear, useful reason that millions of us turn into hothouse tomatoes, one that will become obvious as time goes on, and we’ll know for certain why we’ve been blessed by this variation — a beautiful adaptation that will protect and preserve us, and give us a better chance of surviving.

Los Angeles Times Food Videos

How to make this extra limey guacamole

6:55

The best Black-owned coffee shops to visit in Los Angeles

5:38

Making no-waste chocolate at this L.A. Michelin-star restaurant

5:12

How L.A. schools feed up to 300,000 meals a day

6:52

How Tito's Tacos food is made

9:52

Testing gas and induction stoves to see which is better

9:12

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.