Okra is so much more than its slimy reputation

- Share via

When I mentioned recently to a friend that I was developing some recipes highlighting okra, he forced a polite smile and said, “Well, there’s a lot there to work with.” Sensing his distaste, I assured him the recipes would be worth it.

I often find myself trying to convince people that a food they say they don’t like is actually great, but okra may be the steepest hill to climb. Typically, you either love okra or you hate it — either you don’t mind the slime or it repulses you. That sliminess — a survival mechanism that helps the plant store water — is also present in cactus and purslane, as anyone who’s cooked with those ingredients is familiar.

Fortunately, in my home, it’s all love. My partner and I eat okra often and with gusto, working it into lots of dishes in place of the more basic healthful dinner representatives, green beans and broccoli. And though you find it in grocery stores throughout the year, the vegetable always screams “summer” to me because it’s in season from July through September.

It’s a vegetable that deserves a spotlight rather than its reputation as the slimy thing that thickens gumbo. While that Cajun dish may be the only reason okra is known to most people in the U.S., the vegetable’s uses globally are almost too many to count.

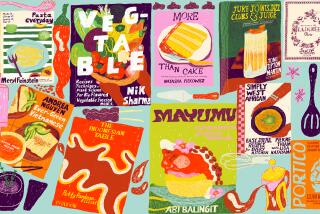

I paged through more than two dozen cookbooks to get the full story of how okra is treated around the world so I can be armed with resources to convert the haters. I found many common themes for dealing with its slime, both in terms of getting rid of it and in terms of using it to the cook’s advantage.

In “My Bombay Kitchen,” Niloufar King sautés okra with green chiles, garlic and ginger and uses it as a base for eggs, a Parsi specialty. In “The Food of Morocco,” Paula Wolfert documents a recipe for “marak of okra and tomatoes,” a melange of the pods and fresh tomatoes mixed with paprika and garlic.

In “Senegal,” chef Pierre Thiam boils it with sorrel to make a green sauce for stewed meat, a common dish in other parts of West Africa as well. Indeed, in “The Africa Cookbook,” Jessica B. Harris chronicles its use from Senegal and Benin in the west to Ethiopia in the east, where it most likely originated. In Sub-Saharan Africa, okra is known — with various similar spellings — as gombo in many of the languages spoken there, linking the vegetable’s use in the stews of the region to those of the American South, where it migrated along the slave-trade route.

But perhaps no region of the world seemingly takes to okra more than the Middle East. From Turkey to Iran and everywhere in between, the vegetable is cherished for its flavor and thickening power. In the Turkish village of Konya, it is dried on strings in summer to use in winter for soups. In “The Turkish Cookbook,” Musa Dagdeviren makes sour okra, stewed in tomatoes with lemon juice. This tradition is also documented in “Feast: Food of the Islamic World” by Anissa Helou, where she simmers the dried okra with tomatoes and lamb for a stew from Konya.

In “Food of Life,” Najmieh Batmanglij stews it with lamb, tomatoes, green chiles and turmeric and then finishes it off with lime juice and grape molasses in a khoresh, or Iranian stew. In the Persian Gulf version of that same dish from her second book, “Cooking in Iran,” potatoes are added, and the sweet-and-sour final flavorings come from tamarind paste and date molasses. It seems okra pairs well with just about any flavor on earth.

In “The New Book of Middle Eastern Food,” Claudia Roden includes a recipe for an Egyptian preparation of sautéed okra perfumed with a garlic-coriander paste fried in olive oil, while Harris’ book recounts another Egyptian recipe for sweet and sour okra in which the pod is cooked with lemon juice and honey.

One of my favorite dishes I encountered came from “Sephardic Flavors: Jewish Cooking of the Mediterranean” by Joyce Goldstein, who soaks okra pods in vinegar water for 20 minutes to strip them of their “slipperiness.” She then braises the okra with chicken in a dish called pollo kon bamiya, made with red wine and pinches of cinnamon and cloves.

I found the vinegar trick more amusing than useful, since I couldn’t find proof anywhere else that it worked. But its use echoed sentiments throughout all the recipes I came across in which okra is cooked with acidic ingredients, most often tomatoes, because the acid seems to minimize the strength of the slime.

Armed with these techniques, I set about developing some new okra recipes that highlight the beauty of the vegetable in all its versatility, both in complementary flavors and techniques. To use its thickening abilities to my advantage, I riff off Goldstein’s chicken dish and braise rendered chicken pieces and okra in a tomato paste-enriched broth, flavored with olives and caramelized lemon to help tame some of the slime.

For those who want all the slime gone, I have two options: My roast okra dish rubs the cut pods with spices, salt and sugar and then blasts them at high heat in the oven until all the slime is driven out of the pods and into the spices to hydrate them. They’re then served over a bed of creamy labneh spiced with chiles, ginger, garlic and spicy, golden turmeric.

And my okra stir-fry rids the pods of their slime by frying them in oil until blistered and caramelized before tossing them with sweet fresh corn and aromatics like garlic, scallions and chiles that accentuate the savoriness of the vegetable.

Though I may not win over die-hard okra haters with these recipes, my plan is to at least show them what they’re missing. There’s more to the pod than the slime, and okra is a vegetable that adapts to almost any flavors you throw at it and any way you want to cook it. That versatility alone is evidence of why it has endured for so long despite its sticky reputation.

Get the recipes:

Braised Okra and Chicken with Caramelized Lemon and Olives

Crunchy Roast Okra With Golden Labneh

Stir-Fried Okra With Corn and Red Chiles

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.