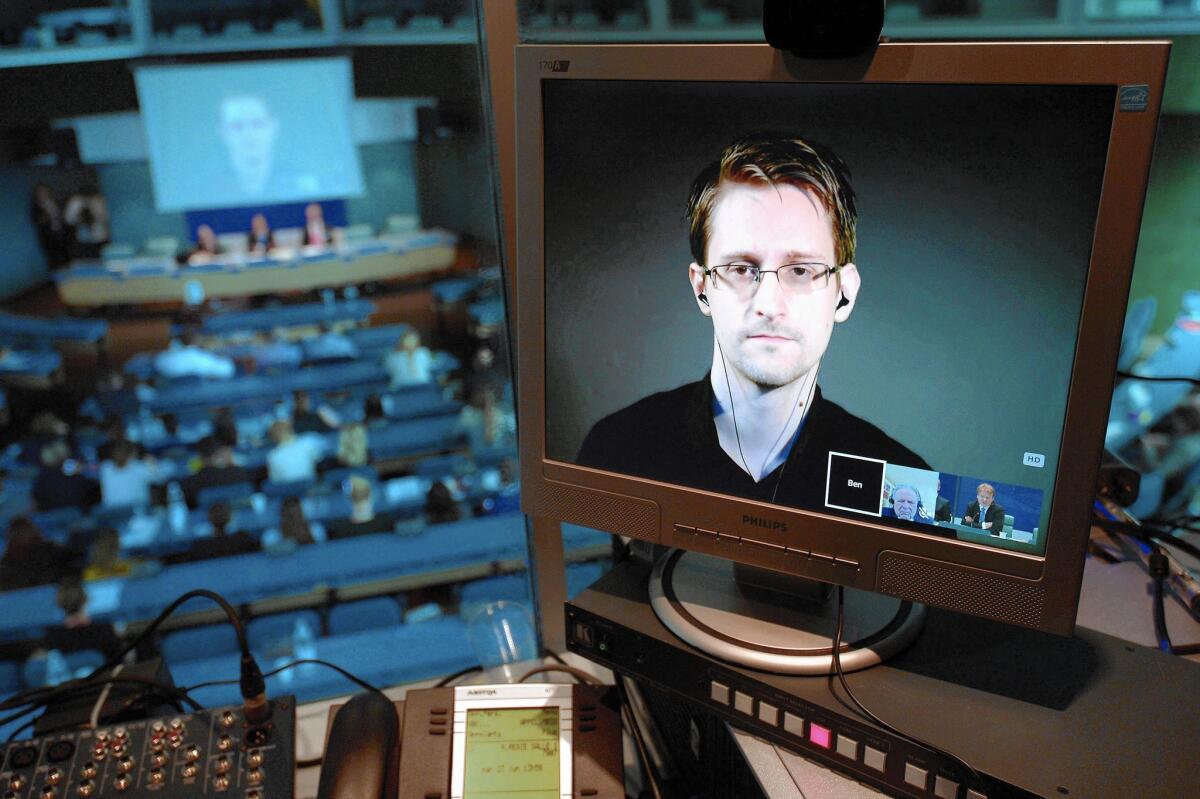

NSA leaker Edward Snowden seeks return to U.S., on his terms

- Share via

Reporting from Moscow — Somewhere in the thousands of towering apartment blocks that ring the Russian capital, whistle-blower Edward Snowden remains in hiding two years after outraging U.S. intelligence agencies with revelations of their snooping into the private communications of millions of ordinary citizens.

Snowden’s release of classified files he took from his National Security Agency contractor’s job blew the lid off programs long said to be aimed at catching terrorists and keeping Americans safe. The leaks triggered a global debate on government trampling of personal liberties and led to last month’s congressional action to end the mass collection of telephone records, the first major restrictions on spy agency powers in decades.

The journalists who were the conduits of Snowden’s disclosures have been bestowed with their profession’s highest honors, as has director Laura Poitras with an Academy Award for her documentary on the fugitive, “CitizenFour.”

SIGN UP for the free Today’s Headlines newsletter >>

The film ends with a glimpse of Snowden in a high-rise window that could be anywhere in Moscow’s populous suburbs, where one building is indistinguishable from the next.

But Snowden has gained little more from his revolutionizing disclosures beyond the sense of accomplishment he is said to feel, according to the few people in and outside Russia with whom he has occasional contact. In rare interviews the reclusive exile has granted, he has said he would like to return to his U.S. homeland but not to detention and interrogation.

Snowden, 32, appears to believe he can set the terms for his repatriation and resolution of the felony espionage charges lodged against him. At this distant remove from American politics and security concerns, however, the young crusader may be counting on an unlikely shift in public opinion.

Although pollsters find many younger Americans applaud his whistle-blowing, the majority express dislike for him, which probably will discourage leading candidates in the looming presidential election from expending political capital on a call for clemency. In a U.S. News & World Report poll in April, 64% of respondents familiar with Snowden said they held a negative view of him.

Even those helping him navigate the blocked pathway home acknowledge that the prospects look grim for the foreseeable future.

“Edward loves America and he would definitely like to return home,” Anatoly Kucherena, Snowden’s Moscow lawyer, said in an interview at his ornate central Moscow office. “But it is our position, and a very simple one, that as long as his case is politicized and commented on as it is by politicians of all levels, that his return to his motherland is impossible.”

Kucherena, who has close ties with the Kremlin, said his client won’t negotiate with U.S. authorities as long as they refuse to provide “a guarantee that he won’t go to jail for 100 years.”

The Russian lawyer who was dispatched to assist Snowden when he was marooned at Sheremetyevo International Airport two summers ago points out that Snowden didn’t defect to Russia, nor did he disclose to Russian intelligence agents the classified material with which he absconded in May 2013.

“It is 1,000% true that he did this as an act of conscience,” Kucherena insisted, noting that Snowden has said he left all the documents he took from the NSA with journalists in Hong Kong.

That is small comfort to intelligence and security veterans who see Snowden’s leaks of classified information and his refuge in Russia as treasonous acts deserving of the felony charges brought against him two years ago under the 1917 Espionage Act.

“Nobody gives credence to his statements that he’s got better encryption than Russians or Chinese can break, especially when they have had the time and incentives they’ve had. So whether he intended to become a foreign agent, he has become one,” said Kori Schake, a National Security Council member in the George W. Bush administration who is now a fellow at Stanford’s Hoover Institution.

She points to the potential for more of the classified information he stole being made public, by him or anyone who has had access to it, as providing little incentive for leniency from the Justice Department.

“If what Snowden did isn’t prosecutable under the Espionage Act, I can’t imagine what would be,” Schake said.

Snowden didn’t set out to seek asylum in Russia. He was reportedly attempting to fly to a sympathetic Latin American country — Cuba or Ecuador — via Moscow. The U.S. government suspended Snowden’s passport as he was en route from Hong Kong, leaving him stranded in an immigration no man’s land at the Moscow airport.

Sergei Markov, an ardent nationalist and Kremlin advisor on diplomacy and international affairs, said Snowden was in need of Russia’s protection because “he can compromise thousands of intelligence and military officials.”

“We can’t send him back just because America demands it,” Markov said, describing the U.S. justice officials seeking the fugitive’s return as a “mafia” intent on revenge.

Ronald Goldfarb, a former federal prosecutor, curated “After Snowden,” an anthology of essays on security versus privacy in the Information Age that examines the fallout from the NSA leaks for the news media, the courts, the intelligence community and the whistleblowers.

“We didn’t begin this book as a defense of Snowden. Everyone has his own views, that he’s either too much an angel or too much a devil. But he has raised profoundly important issues,” said Goldfarb, who advocates a more moderate prosecution of Snowden in light of the surveillance reforms that have resulted from his disclosures.

Goldfarb points to Snowden’s claims — and NSA officials’ denials — that he attempted to take his concern about surveillance excesses to higher-ups at the agency, who turned a deaf ear.

Determining what information Snowden stole and whether it fell into the hands of hostile governments is also necessary, he said, to assess “what damage he caused other than embarrassment” of intelligence officials who lied about the scope of domestic surveillance.

“It would be wise on both parties’ parts for him to plead guilty to the technical crime he’s committed. There is no question he took property he shouldn’t have taken,” said Goldfarb, whose work for the Justice Department goes back to the Kennedy administration.

“Let’s give the government the benefit of a doubt. If Snowden has hurt us in ways we don’t know yet, we need to take that in mind. If not, the case can be made for a modest as opposed to severe sentence.”

Even if Snowden was willing to return to the United States and face trial with assurances of a light sentence and possible clemency when President Obama leaves office in January 2017 — and that deal isn’t on the table yet, those privy to the back-channel negotiations say — the window for taking that risk is closing.

Any deal could become grist for debate in the upcoming presidential campaign, and it seems unlikely that candidates with a serious chance of getting nominated would risk standing up for the perpetrator of one of the biggest national security data breaches in history.

“This is the wrong time for the politics of it,” Goldfarb said.

Ben Wizner, a staff attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union representing Snowden, acknowledges that his client isn’t likely to be going home soon.

“Right now he has two choices: Stay indefinitely there or report to a U.S. prison,” Wizner said, alluding to the charges that could bring a 30-year term.

Snowden feels that time is on his side, Wizner said, not just because of his youth but also because he is able to advance the global debate on privacy rights and judicial reform, even from the unlikely refuge of Russia.

“The reform we’ve gotten so far, albeit historic, is totally unequal to the challenges we face,” Wizner said. “We still have a lot of work to do.”

Twitter: @cjwilliamslat

ALSO:

Death penalty is sought against James Holmes, but governor stands in the way

Sandra Bland arrest video wasn’t edited, had technical problems, Texas officials say

Interviewing Obama, Jon Stewart gets serious for a moment

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.