A lasting glow instead of flash

- Share via

Gerard Colcord’s wouldn’t be among the first names dropped in a discussion of 20th century Los Angeles architects. He isn’t as famous as contemporaries Wallace Neff or Paul Williams, nor do his homes command the premiums frequently tacked onto the prices of houses designed by Modernist darlings Richard Neutra or Rudolf Schindler.

At Hennessey + Ingalls, the vast Santa Monica art and architecture bookstore, no monograph on Colcord can be found among the stacks, because none exists. But customers frequently ask for one, and Colcord has become enough of a brand for pretenders to advertise homes for sale as “Colcord-like.” And that would be what?

Imagine a fieldstone and clapboard farmhouse with deep bay windows, a roof of dark wood shakes and an arcaded front porch, nestled among mature trees. A white picket fence separates its front yard from a street uncluttered by sidewalks. The sturdy front door opens, and a young Bing Crosby steps out into the sunlight, smiling. Or maybe the man of the house is Jimmy Stewart. In any case, a wholesome paterfamilias belongs with the rustic film-studio Connecticut house, because both are redolent of a good time in a prosperous America, a confident, happy place that hadn’t yet become Prozac nation.

From the late 1920s into the ‘70s, about 100 private residences designed by Colcord were built in some of the most attractive neighborhoods on the Westside of Los Angeles. The exact number is unknown because the architect, who lived from 1900 to 1984, was more concerned with making a living than burnishing his reputation; his archive was not donated to a university, and although he married three times, he had no children to tend his legacy.

But an architectural pilgrim can still find his Pennsylvania country houses, Tudor mini-mansions, New England farmhouses and Cotswolds cottages on the leafy streets of Brentwood, Pacific Palisades, Westwood, Bel-Air and Beverly Hills. Some are made of whitewashed brick, others of stucco and stone now covered with ivy. Colcords were also built in and around Coldwater Canyon, in Holmby Hills and occasionally farther east, in Hancock Park, Pasadena, San Marino and Pomona.

“For what they are, Colcord houses are really the best there is. Gerry was one of the most sought-after architects for people who wanted a truly traditional house,” says William Krisel, who got his architectural license in 1950 and went on to design thousands of homes and public buildings in L.A. and Palm Springs. At the time, Krisel says, a local architect like Colcord would work for one client at a time.

“In a practice like his, it would be normal to do two houses in a year,” he says. “Each was very personal. He remained good friends with a lot of his clients, which is unique; people who lived in Colcord houses loved them.” Yet Krisel is surprised that Colcord’s oeuvre is still appreciated. “It speaks well for Gerry Colcord that today people want to restore his houses. Within the profession, architects didn’t think too highly of his work because he was copying the past.”

Krisel’s style was contemporary, and Modernists are typically contemptuous of traditionalists. Isn’t a 19th century Cape Cod built in Westwood in the 1930s a phony re-creation? And what’s an East Coast saltbox doing in Southern California anyway?

“The criterion for creativity is doing something that’s unique, that hasn’t been done before,” says Robert Timme, dean of the USC School of Architecture. “But except for the midcentury modern style, which came out of an industrial movement, everything is really reinterpretations. Even Greene & Greene houses were transformations of Tudor homes with an Asian influence. Gordon Kaufman’s Greystone Mansion isn’t authentic, but it’s wonderful.”

The houses with early American and British roots that Colcord specialized in were historical revivals arguably as valid as the Spanish Colonial or Mission-style houses built in the same areas after World War I. Nearly everyone came to the West Coast from somewhere else, and as they invented their futures, the houses they chose weren’t necessarily reminiscent of their pasts. When architects who mined the styles of other regions and eras were hired, all that mattered was that someone’s history be referenced.

All over Los Angeles, many houses as old as Colcord’s creations have been torn down, replaced by larger, showier structures — sprawling Moorish haciendas and bloated neo-Palladian villas. Some Colcords have been destroyed by wrecking balls too, but not many. “People want to preserve Colcord’s houses because they have a great sense of proportion and a level of craftsmanship and quality that isn’t easy to find these days,” says Crosby Doe of Mossler, Deasy & Doe, a real estate agency that specializes in historic and architecturally significant properties. “His houses are part of the fabric of Los Angeles. People who know about Colcords look for them and ask for them by name.”

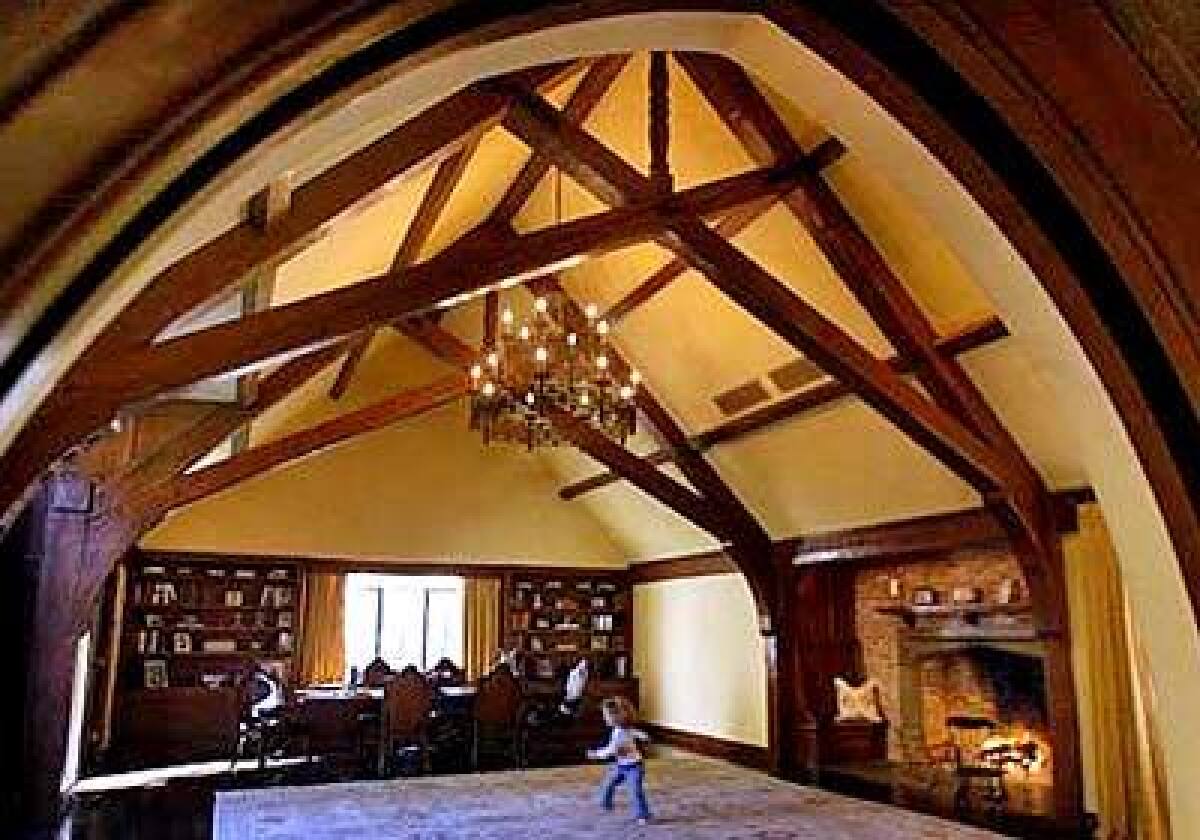

Others become fans by accident. One month before Laura and Sanford Michelman were to move into a home they’d extensively remodeled, they went to look at an elegant Tudor in Bel-Air built in 1969, even though it presented itself as an older, if well-preserved, dowager. The stucco and brick house with half-timbers painted slate blue had peg-and-groove floors, lots of built-in storage, leaded windows and cathedral ceilings accented by exposed beams. “We fell in love with the house and decided not to let it go,” Laura Michelman says. “We were told it was done by a famous architect, but we didn’t know anything about him.”

They learned. At first, they wondered why the fireplace in the family dining room had a big wooden beam across the top. Isn’t that a fire hazard? A workman pointed out that the beam was actually molded concrete given the color and grain of wood. In most of his houses, Colcord employed an Italian craftsman to create the “wood” hearth beams.

At least 50 Colcord originals remain as testaments to the popularity of homes with a feeling of and for history, even if they hark back to an apocryphal past. Of course, in Los Angeles you never know when fantasy and reality blend: Jimmy Stewart’s 70th birthday party really was held in a friend’s Colcord house on North Beverly Drive.

Long before a glut of magazines and TV shows cemented the late 20th century as the age of celebrity, architects, interior designers and artists were often judged by the company they kept. Neff built houses for Hollywood royalty. When Brad Pitt and Jennifer Aniston bought a grand Neff house in the Hollywood Hills built for a movie star couple in 1933, the architect’s reputation acquired new luster.

Through the years, actors, producers and studio executives owned Colcord houses too, but he never got the sort of gilt by association that style makers can bestow. Robert Wagner lived in a Colcord. So did Bob Newhart, Richard Chamberlain, Reese Witherspoon and Ryan Phillippe. But even if Madonna had shared a Colcord with Rudolph Valentino, the architect’s appeal would never rest on celebrity provenance. And while today several of his houses sit next to Neffs in neighborhoods where dogs are walked by the help, he also designed many modest family homes.

The Brentwood house that Jennifer and Christopher Lewis bought in 1992 had been built in 1953 for James Aubrey Jr., then a rising TV executive, and his wife, actress Phyllis Thaxter, on what had been Frank Capra’s citrus grove. Although construction cost $45,000, a substantial amount at the time, and the house is surrounded by enough land to accommodate a yard, pool and tennis court, it isn’t huge or fancy. The living room is dominated by an open brick fireplace and the distressed wood ceiling beams that were among Colcord’s trademarks. Built-in bookcases, one concealing a secret closet, are adjacent to the hearth. With the help of architect Ward Jewell, who had designed an expansion when the house belonged to Jennifer’s uncle, the couple made more changes as their family grew. But they wanted the house to retain the charm it had when they first saw it 15 years ago.

Lewis told his wife’s uncle then, “If you ever put this place on the market, you have to let me know.” He did, and the Lewises lived in the house for 10 years before remodeling. Colcord often put children’s bedrooms upstairs and the master bedroom on the first floor. Jennifer Lewis wanted to preserve the quirkiness of her home’s layout.

“You don’t usually walk into a house and see into the bedroom,” she says, “but that never bothered me. The size of the house is very manageable. It’s livable. We wanted to keep it small and quaint. What I love about it is everything centers around one room — the living room. When I’m at home, I love being able to see my three children, to know what they’re doing. I could use a den and an office, but I like the way we don’t lose touch with each other in this house.”

When Colcord aficionados talk about their houses, their vocabulary runs to the gemütlich: Homey. Cozy. Warm. “Warmth was very important to Mr. Colcord,” Lea Rasmussen says. She and her husband, Art, live in the 1936 Colcord farmhouse they bought in 1974. The couple met the architect when they asked for a set of blueprints. “He was slim and quite dapper, and very much a gentleman,” Mrs. Rasmussen recalls. “He dressed like a banker, in a three-piece suit. He used the word ‘elegance’ a lot.”

In 1996, a music industry executive moved into a 5,000-square-foot English manor that Colcord designed in 1929. The owner carefully restored and updated a number of rooms, and he put the house on the market recently. He’d first seen it as a child growing up in the neighborhood. “I’ve always been interested in architecture,” he says, “and the details in this house are extraordinary. It isn’t a small house, but it’s the antithesis of the big, glitzy places being built now. The scale of the rooms is intimate, and it has lovely arched doorways. This house has character. It has soul.”

The indefinable quality that Colcord dwellers describe can be as perceptible to them as the scent of a lover’s perfume. Bruce and Toni Corwin have lived in a 1940s Colcord in the flats of Beverly Hills, one of three on their street, since 1972. A few years ago they were at a fundraising event in Holmby Hills, at the home of a Hollywood producer. The house was an American Colonial, not a style usually associated with Colcord. “I was looking around, and I got this eerie feeling,” Toni Corwin says. “I asked the owner if it was a Colcord, and of course it was. I just knew.”

Finding Colcords can lead to Colcord clusters. On one short block near the Riviera Country Club in Pacific Palisades, two majestic Colcord houses were built side by side, and a third sits across the street. There’s a smaller, less regal Colcord, built decades later, around the corner. Another, a brick house that would be convincing as the gatehouse of an estate in the Yorkshire countryside, is a short walk away. Residential architecture is a word-of-mouth business, so it isn’t a mystery how the groups of Colcord houses came to be.

Mary Jane Hanson and her husband, Wayne, still live in the Brentwood house Colcord designed for them in 1951. She remembers a couple who had bought a lot around the corner asking about the architect the Hansons had used. “I told them he was wonderful,” Hanson says. “I loved working with him. He was so knowledgeable and such a perfectionist. He was so in demand that you’d think he’d have a big ego, but he didn’t.”

The couple, Andy and Jane Andreson, commissioned a Colcord house that was completed in 1957. Mrs. Andreson lived there till she died. “I adored the house, and I would have loved to have kept it in the family,” says daughter Sally Vena, who was a teenager when her family moved in. Given the whopping cost of Brentwood properties north of Sunset, Vena’s adult children couldn’t afford it, but they all wanted to find the right buyer. “If someone had bought the house and torn it down, my children and I would have been extremely upset,” she says. “It was important to us that the house be saved, even if that meant taking less money.”

Caryl Golden, an interior designer who’d been on the hunt for a Colcord for more than two years after losing one in Bel-Air to a higher bidder, bought the Andreson house. Vena gave her the original blueprints and a book of sketches Colcord made of the interiors. When a restoration and remodel designed by architect Jewell is completed, the front of the house will still look very much like Colcord’s drawing, but bedrooms and bathrooms will be added, closets expanded and the kitchen updated.

“We call it ‘Caryl’s Folly,’ ” Golden says. “It would be much simpler to tear that house to the ground and build a new one. What we’re doing makes no economic sense whatsoever. My husband has an expression: He says Colcord houses hug you.”

Curators of midcentury modern glass boxes treat them with the sort of reverence accorded long-lost Rembrandts. The cult that appreciates Colcord is smaller and less doctrinaire, even if its sense of stewardship is great. Golden says, “Even though we’re doing as much work as we are, I want to keep the stylistic integrity of the house. We’re keeping the Douglas fir paneling, the brick fireplaces, the beams, the staircases, which are great. We’re milling all the baseboards and the doors to match the old ones. The original windows have decorative trim, and we’re going to match that. We’re trying to match the old hardware too. We’re keeping as much of the brickwork in the kitchen as we can. Every time you’d open a cabinet you’d find special little appointments you don’t find in new houses. Colcord designed a knife rack we had to rip out, and there’s a spice rack. Under the dormer windows in the upstairs bedroom, there was storage hidden beneath the window seats.” Jane Andreson asked Colcord to create that space so her daughter Sally would have a place for her circle skirts.

“My mother was at the house the day the beam over the fireplace was made,” Vena says. “When the concrete was still wet, she drew a heart, then carved her and my father’s initials in it.” The wide brick chimney was demolished when work on the house began late last year, but the faux wood beam, signed nearly 50 years ago by a young wife and mother building her dream house, survived.

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

Elements of Colcord style

Wood

Exposed rough-hewn wooden beams gave big, high-ceilinged living rooms and cozy family dining rooms rustic character.Wide-plank wood floors, like those found in country houses built a century ago, were used throughout many houses.

Paneling of Douglas fir or stained pine covered the walls of family rooms, dens and living rooms.

Kitchens were constructed with built-in spice and knife racks.

Masonry

Exteriors were paved with fieldstone and other irregularly laid stones with wide mortar joints.

Fireplaces of old brick were sometimes built oversized — wider and taller than several children standing together.

Large, distressed faux “wood” beams hung above stone or brick hearths were actually cast in concrete.

Windows and doors

Leaded glass windows in a traditional diamond pattern gave houses an old English look.Dutch doors adorned with antique hardware were often used in kitchens and elsewhere.

Homes of more than one story featured dormer windows in gable roofs covered with dark wood shakes.