An original composition

- Share via

A single, elegant vase sat in the kitchen window of the high desert retreat built by late composer Lou Harrison.

As the first light of day crept in, documentary filmmaker and concert promoter Eva Soltes, who worked with Harrison on numerous projects over three decades and now owns the house, looked up at the vase and smiled.

“That’s Lou,” she said quietly.

The comment could have been taken as her describing the ornate object as just the kind of thing he loved. So she laughed and added, “That really is Lou.”

Soltes pressed her hands together and bowed slightly toward the window. The ashes of Harrison, who died on Feb. 2, 2003, at age 85 while en route to a festival of his musical works, were inside the vase.

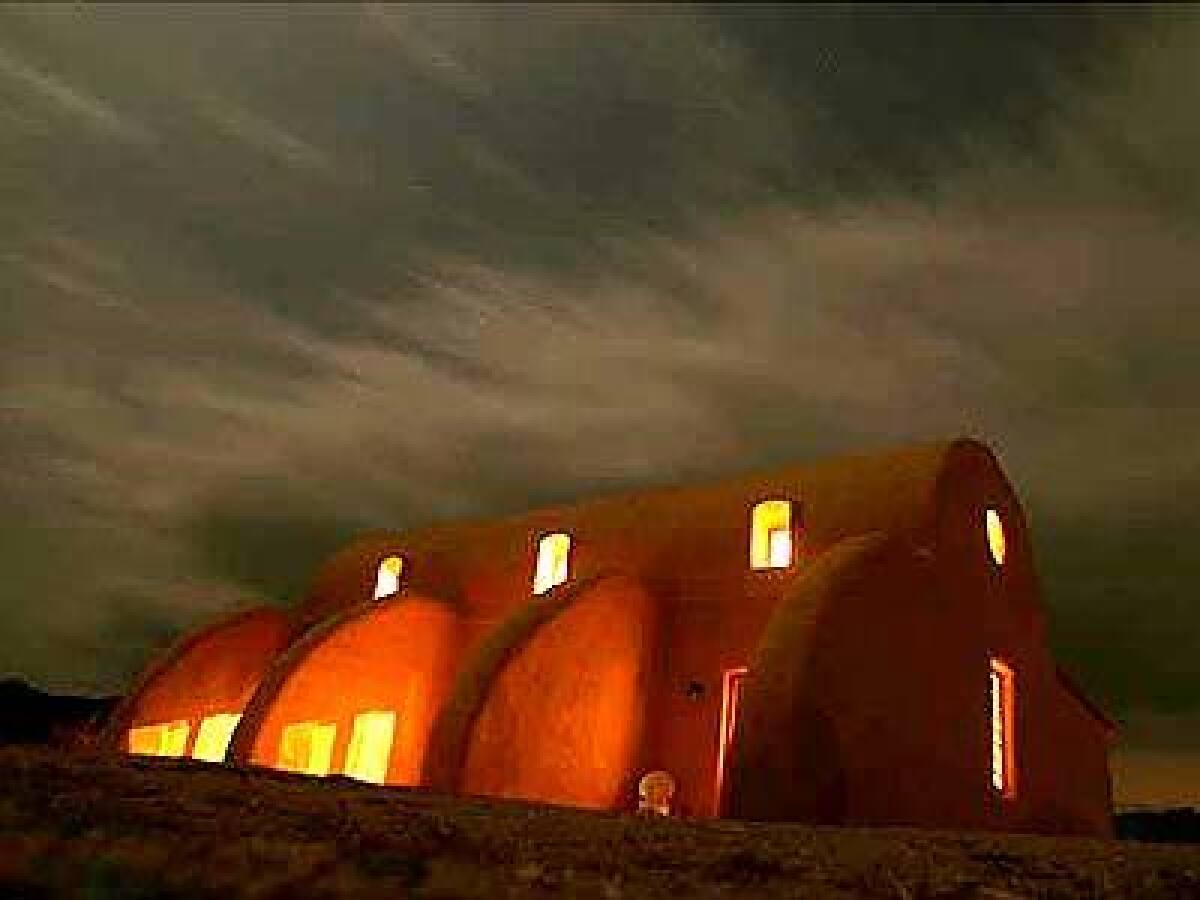

The house, built against a stunning backdrop of huge granite rock piles common to this landscape near Joshua Tree National Park, is very much representative of what Harrison — for whom the term iconoclast seemed coined — was all about.

Like Harrison — who incorporated Baroque, Asian and a wide range of other musical forms into complex, achingly beautiful works — it’s a glorious mixture.

The retreat is dominated by a soaring, arched roof that took design cues from both mosques and medieval cathedrals. It uses traditional materials in an experimental way, so much so that it took almost three years to get through the permitting process. It was built in large part by a community of people, some of whom were longtime friends and admirers of Harrison and others who were lured by the novel way in which the house was constructed. And finally, it has strong ties to the environment.

Inside the retreat’s 2-foot-thick walls, the primary building material is tightly bound bundles of straw. Straw-bale construction — a rapidly growing nationwide trend — was used because of its recycled materials, low cost, malleability and insulating quality that makes heating and air-conditioning more efficient.

But while most straw-bale houses end up looking either quite conventional or like something out of a hobbit village, the Harrison retreat is so elegant and awe-inspiring that it’s not unusual for first-time visitors to drop their voices to a whisper as they step through one of its many doors into the main hall.

Soltes was visiting from her regular home in San Francisco to host a small celebration — with music, dance and the scattering of those ashes in the desert — to mark the first anniversary of his death and to look toward the future of how the retreat would be used, perhaps as the core of an artists’ colony.

Harrison was a man of ample girth and flowing white beard, which led to his being referred to as the Santa Claus of new music. His work, though long respected in music circles, did not become widely known until his later years, when it was performed by the likes of the San Francisco Symphony, Yo-Yo Ma, the Kronos Quartet and Keith Jarrett.

He had a wide network of friends, a legendary thirst for knowledge and a just-as-legendary generous nature. “When Lou found a book that he liked, he would buy at least three copies,” said George Zelenz, an architect who lives nearby. “One for himself, one in case the first got lost and one for a friend he thought might like it.”

Many of Harrison’s close friends were involved in his broad range of projects, including the building and playing of gamelan, an orchestra of bell- and marimba-like instruments native to Indonesia for which Harrison wrote numerous pieces.

But woe to anyone who confused his jovial persona with permission to vary from his precise ideas for how he wanted his music performed. And that goes for other expressions of his artistry too, including the house.

“He thought of it as being made up of modular pieces in the way that gamelan music is modular,” said Chris Daubert, an artist and furniture-maker who built several instruments for Harrison.

“Traditional gamelan pieces are short and repetitive, and then embellishments are added to the simple structure. In that way, you can think of the house as starting out with nine modular pieces, almost like a tic-tac-toe board.”

On the south side, the three pieces are the equally sized kitchen, bathroom and bedroom.

The three pieces of the design puzzle on the north side are not exactly rooms, but equally spaced, outdoor patios, set apart by graceful arches. Soltes said that Harrison spoke of perhaps enclosing these spaces someday, making them into additional bedrooms.

But the heart of the house, figuratively and literally, is the great room in the center that is the combination of three of these modules with no walls in between (imagine the three squares down the center of the tic-tac-toe board and then erase the top and bottom lines of the center square, leaving you with one long space).

Although not a large room, area-wise, its drama derives from its being three times bigger than the others and, most importantly, from the fact that its thick gray walls climb 22 feet to a vaulted ceiling that gives the house its cathedral-like feeling, making the retreat seem far larger than its total of 1,000 square feet.

The smooth walls of hand-applied plaster give the doorways — there are six leading to the room — a sculpted, sensual look.

There are other dramatic touches that give this room a quieting, exalted feel. The entire east side is a vaulted window — providing a striking view of the sunrise — that was built by Daubert to withstand 100-mph desert winds.

On the outside of the window is a wooden lattice, made up of rows of triangles, called a mashrabiya in Arab desert countries. It diffuses strong sunlight.

Harrison would not allow his desert retreat to be built without the Romanesque, vaulted ceiling, not only for appearance, but also for the incredible spaciousness of sound it would give to live music played in the room.

That vault ended up causing painful delays, not to mention a great deal of heartbreak, during the building of the house. But it also helped lead to this little retreat forging into new territory in housing, and its legacy is already being felt on the other side of the world.

Harrison started telling friends in the early 1990s that he wanted to build a second home to get away from the intrusions that had come with growing fame.

“Our house has turned into a sort of office,” he explained in a speech before the American Humanist Assn. “We intend to build a getaway house. If I have a project that I want to take, I can take it there and complete it undisturbed.”

Harrison’s primary house, shared with life partner William Colvig — an electrician by trade who built numerous Asian instruments with Harrison — was in coastal Aptos, near Santa Cruz, Calif. Both men were in fragile health and thought that spending at least part of the year breathing dry desert air would help. But not much money was available for buying land and building a retreat. Commissions for serious music are not bountiful and all but a tiny handful of serious music composers in this country have to teach or otherwise supplement their incomes, even when in demand.

“He started a special bank account,” said Soltes, “and when he would get a commission, he would say, ‘That’s for the house.’ ”

On the way home from a concert event in New Mexico in 1995, Harrison stopped off to see Zelenz, who shared his interest in gamelan music. “I drove Lou around in my truck for a couple hours, showing him the different neighborhoods,” said Zelenz. “A couple days after they got home they called and asked me to find them some property.”

Zelenz found a 1.25-acre lot in a failed development for about $8,000, sent them pictures, and they bought it.

Harrison and Colvig, both ardent environmentalists, were committed to straw-bale construction. It recycles straw, which is essentially a waste material, and provides bountiful insulation to cut back on energy use.

The Skillful Means construction and architecture firm, which specializes in straw bale, was engaged. Harrison’s design ideas were influenced by famed Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy.

Luckily, project architect Janet Johnston had visited whole desert villages Fathy had designed.

“Originally, we had not only the vault, but three domes — one over each of the single rooms,” said Johnston.

The original plan was to seal the straw-bale insulation with gunite, a strong concrete mixture that can be blown onto a structure. But during the planning stage, the cost of gunite skyrocketed, placing it far beyond the modest $70,000 budget for the retreat.

The house ended up costing Harrison a lot more — about $125,000. Still, Skillful Means officials said their company lost money on the project, due to the extra costs they absorbed.

The backup plan was to use stucco, but in seismically active Joshua Tree that would have required an interior wood frame to meet the code. And the vault and domes would have to be eliminated.

Harrison was willing to let the domes go, but not the vault.

Delays began. Finally, a prominent seismic engineer in the Bay Area, David Mar — who had worked on San Francisco’s Ritz-Carlton hotel and several downtown commercial buildings — heard about the project. He was intrigued and took the job pro bono.

At that point Mar had never heard of Harrison.

“I was invited to the concert of the San Francisco Symphony with Michael Tilson Thomas conducting his music,” Mar said. “It blew my socks off.”

Mar came up with a theoretical solution, and a full-scale, prototype vault was made for testing. It passed easily, Mar said, showing integrity more than three times the code. But code officials still balked.

As delays grew longer, costs and frustrations mounted. But saddest of all, Colvig — who had shared Harrison’s life since 1967 — died in 2000.

Finally, a compromise was negotiated. An outside engineer could be hired to go over the plans. The cost of this was shared equally by Harrison, Skillful Means and Mar. The engineer gave them a passing grade and construction finally went ahead full speed.

When it came time to stack the straw bales in the walls, volunteers — including Daubert, Johnston, Mar, Soltes and Zelenz — came from all over California. That part was done in two weekends.

Soltes, who is making a feature-length documentary about Harrison, was on hand to film the moment, on Feb. 2, 2002, when the house was declared finished and the proud owner rushed in to play a gamelan for the first time in the main room. (Clips from the in-progress documentary are at https://www.harrisondocumentary.com.)

A year later to the day, Harrison was gone, having had the chance to take only about five trips to his retreat. On the last of those, in November 2002, guitarist John Schneider played him what turned out to be the composer’s last major piece, “Scenes From Nek Chand.”

“He really enjoyed it,” said Schneider, another longtime Harrison associate, “and I was so glad. Who could have known it was the last time?”

Sitting in front of the main window, on a blustery night of the celebration, Schneider played it again. It was spacious, haunting music, so appropriate for the desert setting. And the sound in the room was luminous.

The ashes were spread outside and Zelenz read an epic poem by Harrison, mostly concerning the death of Colvig. One passage was about the musical instruments they built together.

It ended: “They will sing his lasting voice into the future, for we lived a covenant of love and tune.”

The integrity, adventurousness and stubbornness with which Harrison took on the project of building his house will likely play a future role in the lives of many people who will never hear his music or know of the Joshua Tree retreat.

“We proved that you could make housing appropriate for areas with high seismic activity for very low cost — maybe $4 a square foot in parts of the developing world,” said Mar. Of course, this would be without a vault. But a plain home that can withstand strong earth tremors and still be afforded in poor areas could save lives.

“More than 400 of these houses have already been made in China,” Mar said. “Lou would be so proud.”

*

A sampling of his work

For a sampling of Lou Harrison’s music, go to https://www.musicmavericks.org/listening to hear a San Francisco Symphony concert — conducted by Michael Tilson Thomas — devoted to his works. An interview with the composer also is on the site. Notable CDs include:

Piano Concerto (New World Records), performed by Keith Jarrett and New Japan Philharmonic Orchestra.

Rhymes With Silver (New Albion Records). Music written for Mark Morris Dance Group.

Just Guitars (Bridge Records), featuring John Schneider.

Gay American Composers (Composers Recordings), includes Kronos Quartet playing two movements of his string quartet.

Lou Harrison: A Portrait (Argo). Selections performed by the California Symphony.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.