The artistic evolution of the Sobieski house

An innovative South Pasadena house treats living spaces like art galleries. For the Sobieski family, each household function -- sleeping, dining and more -- takes place in its own small building, and the garden spaces in between are just as important.

- Share via

When the Sobieski family bought a run-down ranch house in South Pasadena, they imagined that they would replace it eventually. But they didn't anticipate the unconventional form its successor would take: a mix of small, free-standing buildings and a series of linked rooms masquerading as separate pavilions, some opening onto gardens -- and every space an impromptu gallery for the family's medley of artwork.

The story begins in 2002, when the family moved into that 1940s ranch house, with its leaks and rotting floor, and discovered how it actually enhanced their way of living.

"It was so non-precious that kids would ride bikes right through the front door and so laid-back that friends would come by to nap on the couch," Anne-Elizabeth Sobieski recalled of life there with her husband, Jamie, and their sons, James, now 15, and Oliver, 14. They wanted to carry that spirit of casualness and improvisation into their next home.

But they stayed put for more than seven years while Anne-Elizabeth prepared for her master of fine arts in painting and Jamie, whose career has spanned from stock trader to chef to gallery owner, completed a law degree. The pause gave them time to consider the potential of their 0.6-acre site.

It's a flag lot, accessible from the street via a long driveway, the pole. The flag itself is surrounded by neighboring yards and buffered by hedges.

Such unusual privacy inspired the Sobieskis to push the concept of indoor-outdoor living. They envisioned giving each household function, such as sleeping or dining, its own small building. That would allow the in-between garden spaces to become as important as the inside rooms.

They began in 2005 with just one building: Anne-Elizabeth's simple, white-stucco painting studio, designed by architect Warren Techentin, with a steel-ribbed, vaulted ceiling and French doors opening an entire wall to the outdoors. Though pleased with the results, the couple turned to Koning Eizenberg Architecture of Santa Monica to continue the experiment three years later.

Click the "home tour" link above and explore the angles of the home through the green cameras.

Sources: Koning Eizenberg Architecture, Azure, Architectural Record. Interactivity by Lorena Iniguez Elebee, graphics reporting by Tia Lai and photography by Ricardo DeAratanha.

Right away, the site impressed the designers. The driveway leaves the streetscape behind and leads to a large hidden pocket of land where "distinctions between front and back yard disappear," partner Julie Eizenberg said. "The sequence is a fantastic setup for an indoor-outdoor house."

Now at the driveway's private end, a deadpan traffic sign declares: "You will never be the same." It's art -- and a first taste of the Sobieskis' sensibility.

Pass through a gate into the cluster of white, cube-like pavilions on grassy terrain completed by Koning Eizenberg in 2012, and the compound feels like an artists' colony. The resemblance is not entirely by chance. "The Sobieskis really seemed to want art studios where they could live," rather than the other way around, Eizenberg said.

The Sobieski family lived in the guest house, at right, during the 18 months of construction. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times) More photos

By creating varied structures around the solar-heated pool, the architects integrated the existing studio into the mix. The approach dovetailed with the owners' request for phased construction, sparing them the expense and upheaval of a temporary move off-site.

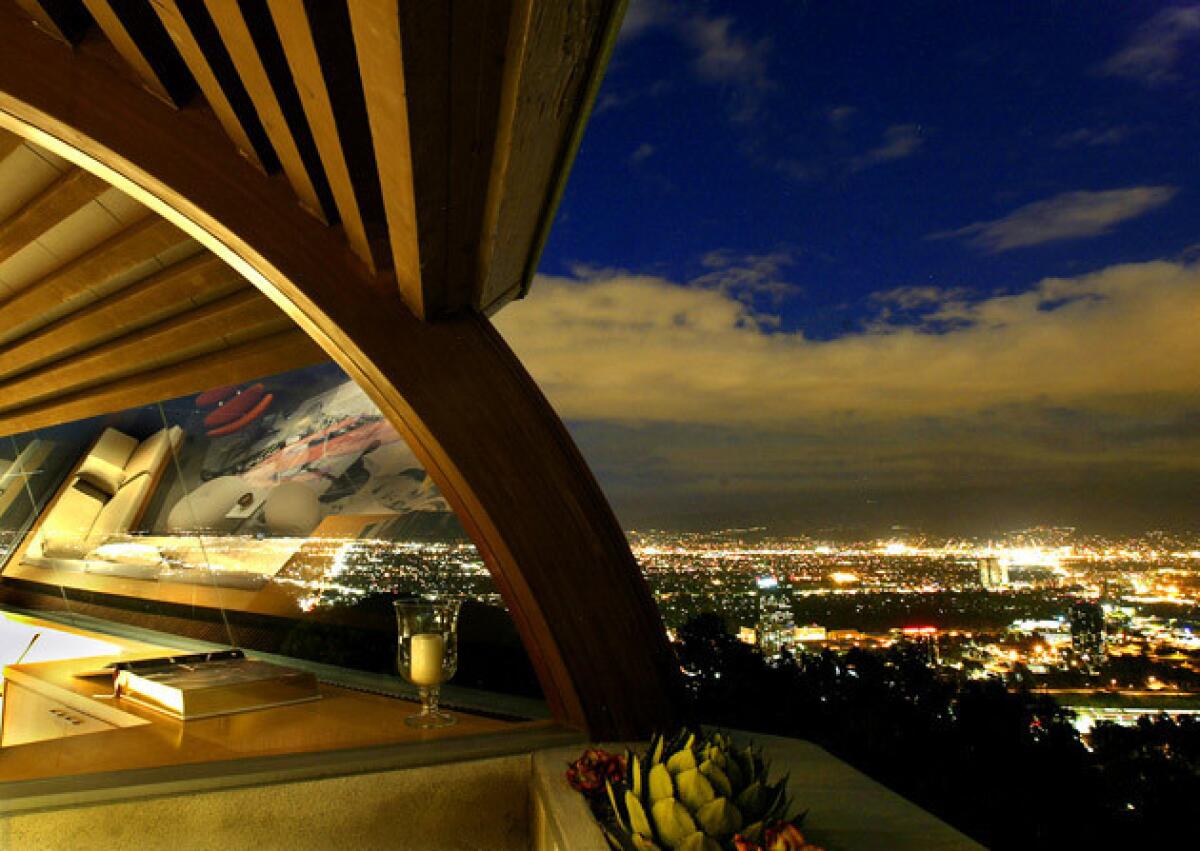

Phase 1, where the family bunked for 18 months, is a 635-square-foot pool/guesthouse with a kitchen, bedroom and sleeping loft. Its exposed wood framing, strand board, metal siding and polished concrete floor play against translucent polycarbonate sheathing that glows, lantern-like, by night.

For Phase 2, zoning disallowed additional pavilions, so the 3,265-square-foot main house merely reads as free-standing white stucco volumes. Its smaller boxes -- the linking forms, housing bathrooms and storage -- are clad in sugi board, or Japanese burnt cedar. Each one has a roof garden and deck.

Fan-assisted earth tubes, chilled deep underground, cool the interiors at nominal cost, even when the sliding barn doors -- big, chartreuse-framed glass panes -- are wide open. Activity spills freely between inside and out. Movies are often projected onto an outside wall. Ping-pong is played beside the living room's grand piano.

The open kitchen has professional steel appliances, tempered by the earthiness of an 18-foot-long oak counter. "It's a kitchen you can hose down like a pro," Jamie said, "but also a place where the kids and their friends can hang out in pajamas flipping pancakes."

The vinyl museum exhibition banner of a Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres painting hangs over the guest house living room. (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times) More photos

Artwork has an equally playful edge, juxtaposing, for example, Pae White's "Popcorn" sculptures and Anne-Elizabeth's paintings with carvings handed down in the family and mural-scaled canvases commissioned in 2007, when the Sobieskis spent a year in Shanghai. An enormous blow-up of a Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres painting covers an interior guesthouse wall, spectacularly recycling what had been a museum's vinyl exhibition banner. Hand-painted reproductions nonchalantly intermingle with original works.

With the compound complete, the guesthouse draws friends and family, and the Sobieskis have already hosted a museum fundraiser.

"We love sharing what we've created here," said Anne-Elizabeth, who occasionally holds art workshops on the grounds.

"We designed the place knowing their lives brim with improvisation," Eizenberg said, "and, in a couple of years, I wouldn't be surprised to find them using it all quite differently."

Photographer Ricardo DeAratanha wrote about the process of photographing the Sobieski home — and other houses — for L.A. at Home. Read his article in our Los Angeles Times photography blog, Framework.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.