From the Archives: Pompous diva or fun-loving friend? Carly Fiorina presents a sharp contrast in images

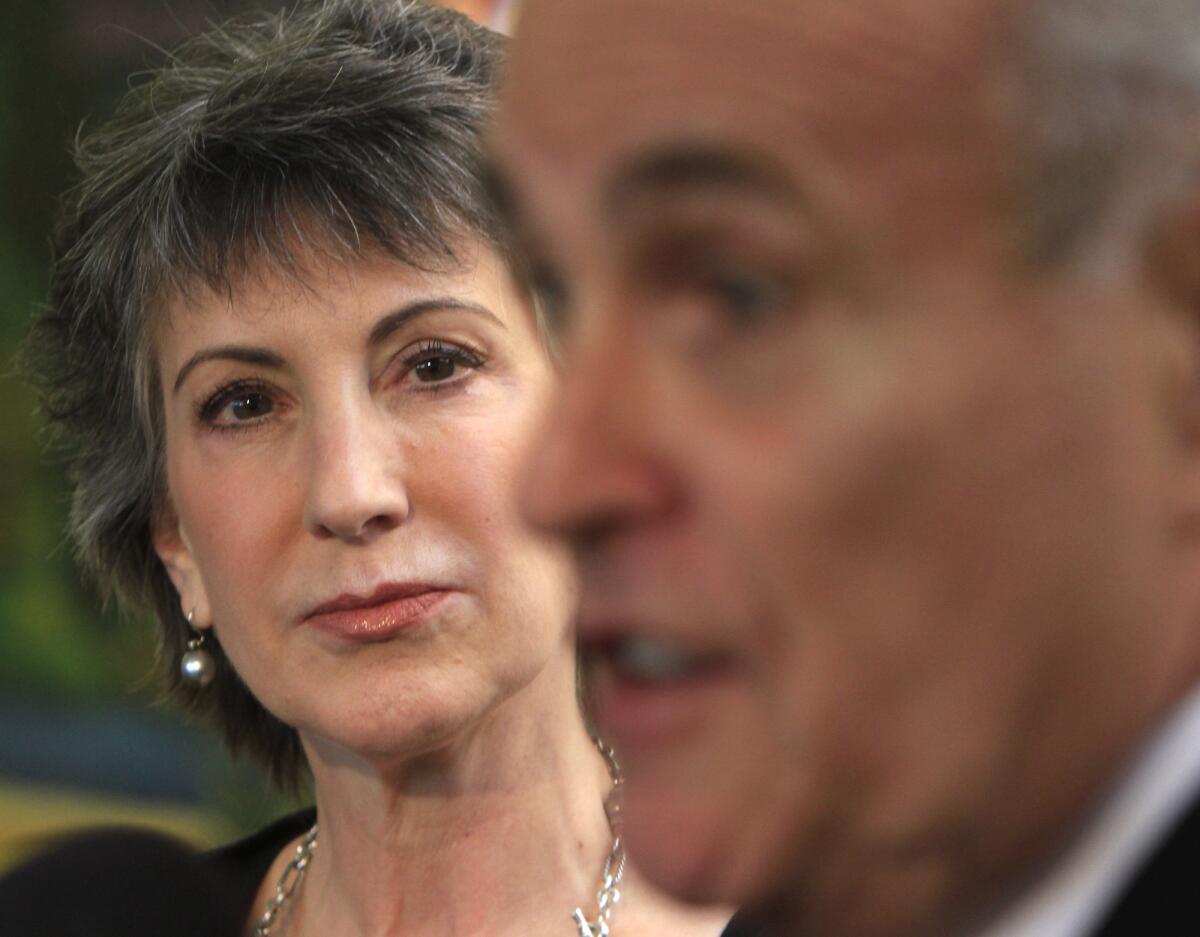

Carly Fiorina looks on as Former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani endorses her during a news conference at the Asian Garden Mall in Westminster in October 2010.

- Share via

One night a few years back, a California communications executive named Deborah Bowker was worried about her husband, who was sick and hospitalized. An old friend told her she shouldn’t be alone, that she should come over and stay the night.

The guest bedroom at the friend’s house was used most often by grandchildren, and contained two tiny beds. That night, Bowker was crying herself to sleep in one of them when the door cracked open. Without a word, Carly Fiorina padded across the room and crawled into the other bed.

Bowker and Fiorina have been close friends since they went to MIT together, and little changed for 20 years — until Fiorina decided to run for the U.S. Senate, with Bowker as her chief of staff.

CAMPAIGN 2016: Get the latest news on the presidential race on Trail Guide >>

That fretful night doesn’t seem like a big deal now. Bowker’s husband recovered, and Fiorina might not even remember it, Bowker said with a laugh. Bowker said she hadn’t told the story before and wasn’t sure why she was telling it now — except that she hardly recognizes Fiorina in the image that’s been created through the veneer of politics.

Those closest to Fiorina, 56, describe her as loyal and fun-loving, witty and bright. But they are well aware of the other image — of a pompous diva, aligned with the most strident factions of her Republican Party, pampered by a golden parachute after being fired from her high-profile job.

Fiorina the candidate hasn’t always helped matters. Her tone on the stump can be caustic. At one point in her dogged campaign against the Democratic incumbent, Sen. Barbara Boxer, an open microphone caught her belittling Boxer’s hair as “so yesterday.”

In a sneering attempt to connect with a “tea party” crowd near Fresno recently, she referred to San Francisco — the center of the metropolitan area where she spent nearly half of her life, the city just up the road from her 5,400-square-foot Los Altos Hills estate — as “that faraway world.”

And her critics tend to roll their eyes when Fiorina — who was raised on opera and French lessons, was the daughter of a powerful judge and has a sterling academic pedigree — pitches herself as a kind of Horatio Alger. Her journey, she said at one recent campaign event, was “only possible in the United States of America.”

Getting to know the person friends call “the real Carly,” meanwhile, can be a confounding task. Stung by several episodes in her life, including the unraveling of her first marriage and the brouhaha surrounding her firing from Hewlett-Packard, where she was chief executive, president and chairman, she is private and guarded.

Fiorina’s work ethic is legendary, and her discipline is one reason Boxer — a lioness of the left seeking her fourth Senate term — is in arguably the toughest race of her career. But Fiorina can be so on-message that she comes across as a machine.

During a recent heat wave, Fiorina met with business leaders in a sweltering City of Industry warehouse. A visitor joked that the record heat might cause her to rethink her position on global warming. Fiorina was not amused, launching instantly into her talking points about climate change — contending that she reserved the right to “challenge the science.”

On the campaign trail, it can be difficult to envision the Fiorina who could often be found dancing with the interns and the secretaries at the end of corporate parties, long after the other executives were gone. Or the woman who, on a recent boat trip, suddenly disappeared; she had jumped off the stern and hauled herself onto a tiny raft with her step-granddaughters.

Friends say she’s a fair cook and has a nice touch on the piano. She was raised Episcopalian but is not a regular churchgoer. She does Jane Fonda-style aerobics, whether she’s home or on the road.

She reads policy briefs on her iPad but reads books the old-fashioned way. She’s a voracious shopper, said one friend of 20 years, and gave one Hong Kong jeweler enough business that he put her picture in the window. She has at her disposal a household net worth estimated as high as $121 million and yachts on both coasts, and will be one of the wealthiest members of Congress if she wins.

She and her husband, Frank Fiorina, a former AT&T executive with blue-collar roots in Pittsburgh, have been married for 25 years. It is a second marriage for both; she calls him a “hunk” with some frequency.

Last fall, she threw him a sock-hop-themed 60th birthday party, tracking down friends he hadn’t seen in 30 years. Fiorina was stylish as ever, said an old friend, Kathy Fitzgerald, in a black dress and textured stockings — and, since she was being treated for breast cancer, bald.

Cara Carleton Sneed was born in Austin, Texas. Her mother, a talented oil painter, was a refugee from a troubled childhood in Ohio. Her father, Joseph Tyree Sneed III, was a University of Texas law professor whose ambition in academia meant that she was perpetually “the new kid,” she wrote in her autobiography, as the family moved repeatedly.

In 1969, while teenagers across America experimented with a new counterculture, Fiorina was in Ghana, where her father was teaching students about the country’s new constitution.

Fiorina’s father soon joined the Stanford law faculty, and she graduated from Stanford with a degree in philosophy and medieval history — which, she jokes, rendered her unemployable. She bounced from job to job, working as a typist, a temp, a receptionist. In 1980, she signed on as a management trainee with AT&T.

There, the more confident and tenacious she became, the brighter her star shined. She persuaded the company’s chairman to sue the federal government for giving away AT&T’s pricing information; it was a risk, and it worked. She selected AT&T-spinoff Lucent’s red logo with her mother’s bold paintings in mind; it was derided initially as “the million-dollar coffee stain” — and soon widely imitated.

“She just didn’t take ‘no’ for an answer,” said Frank Fiorina, who was a mid-level manager at the time.

In 1999, Fiorina became, by some measures, the most powerful woman in the history of American business — the chief executive of Palo Alto-based Hewlett-Packard Co. Her makeover of HP, especially her push for a $19-billion merger with Compaq Computer, meant tumult for the company and the technology industry. Layoffs — 33,000 by some estimates, though Fiorina says she created more jobs than she eliminated — earned her the disdain of many employees.

She lasted until 2005, and her tenure is viewed in two dramatically different ways, both of which cannot be true.

To loyalists, she was little short of a visionary, someone whose ideas drove up revenues, reformed a once-plodding company and enabled a storied company that helped launch Silicon Valley to survive the “tech wreck” that crippled so many other companies.

“Carly’s strategy is what saved HP — no doubt about it,” said Bill Mutell, who worked for Compaq and retired from HP in 2006 as a senior vice president.

Many analysts call that revisionist history, noting, among other things, that HP stock fell by roughly half during her tenure. One business publication ranked her among the worst CEOs in American history, arguing that she was “posing for magazine covers while her company floundered.”

She was fired, with compensation worth about $42 million.

Jeffrey A. Sonnenfeld is a senior associate dean at Yale School of Management and founder of the Chief Executive Leadership Institute, a training academy of sorts for CEOs. He has studied HP extensively and called it preposterous that she would stake her candidacy on her business experience.

“This board agreed on nothing else other than they would like to breathe in oxygen and breathe out carbon dioxide. The only other thing they agreed on was that Carly ought to be fired,” Sonnenfeld said.

After HP, Fiorina wrote her memoir, “Tough Choices,” and joined the speech circuit, earning as much as $100,000 a pop in Paris, Abu Dhabi, Cabo San Lucas. Her name had been bandied about in political circles for years, and in 2008, she signed on as an advisor to Sen. John McCain’s presidential campaign. Fiorina joined McCain for long stretches, often acting as emcee at his campaign events.

She stumbled on several occasions, particularly after McCain selected then- Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin as his running mate. After Fiorina told an interviewer that Palin was unqualified to run a corporation, her TV appearances were curtailed.

Bowker, Fiorina’s chief of staff, questioned whether Fiorina’s involvement with the campaign was a good investment of her time. She said Fiorina replied: “I’m learning.”

Fiorina announced her bid for the Senate last fall, pledging to work tirelessly to bring jobs to California — partly by increasing agricultural water supplies in the Central Valley — and to “take our government back” by reining in what she calls Washington’s out-of-control spending.

Some of her associates were stunned that she had the energy for a campaign; she was on the heels of chemotherapy and surgery. She seemed to be running not in spite of her cancer, but because of it.

“I watched her draw energy” from the campaign, Bowker said. “It gave her something in her future to look forward to. She’s an unusual person that way. If it were me, I’d want to curl up in a ball.”

The Senate bid is Fiorina’s first run for office, but she has a voting record that is spotty at best and, by all accounts, she had little interest in politics well into adulthood.

“She had,” her first husband, Todd Bartlem, said in a recent interview, “no opinions.”

She set sail against Boxer with the ideological winds of the moment, tapping into the anti-incumbent anger that has swept some portions of the nation. While decrying the partisan divide in Washington, Fiorina has derided Boxer as “an embarrassment” and has claimed that Boxer is backed by environmental “extremists,” although she seemed flummoxed recently when asked to name them.

In a state where registered Democrats outnumber registered Republicans, Fiorina has surprised the political establishment by declining to make many nods toward the center.

She has remained a steadfast defender of Arizona’s controversial immigration law and has not wavered in support of Proposition 23, the November ballot measure that would suspend efforts to curb greenhouse gas emissions. Fiorina has called Proposition 23 a job-saver and was recently feted at a fundraiser hosted in part by the billionaire Koch brothers, who control oil pipelines and have pumped money into the fight.

Fiorina has said she would support overturning Roe vs. Wade, saying her views on abortion were formed largely because Frank Fiorina’s mother was told to abort him due to health risks.

She is something of a sensation among hard-line conservatives, particularly tea party organizations.

“She takes on impossible things, and she accomplishes them,” said Glenda Gilliland, a Fresno Tea Party activist who retired from HP in 2005 and attended a recent Fiorina speech. “I think she will fight — I know she will — for the people of California.”

But Fiorina’s support from hard-line conservatives can make for an awkward dynamic; she appears to be more measured and moderate than they think she is. At recent campaign appearances, for example, several of her supporters volunteered to a reporter — as fact — that President Obama is an African-born Muslim.

Asked whether she’s comfortable with support from that arm of the political spectrum, Fiorina said: “I certainly don’t agree with it. I don’t think the president is a Muslim. He clearly is a Christian. He clearly was born in America.”

Meanwhile, two organizations that have said the Obama administration promotes the “homosexual infiltration of schools” have spent $60,000 on advertising for Fiorina and pledged more. Fiorina’s aides made clear that she does not agree with the groups’ position — and contended that she has no control over who promotes her candidacy.

“One of the things that has happened in politics that doesn’t happen in the rest of life is that people say: ‘Well, if I don’t agree with someone 100% of the time, I can’t work with them,’” Fiorina said in an interview. “And I think it’s why there is so much partisan bickering on both sides of the aisle.”

“In the rest of life … you rarely agree with someone like that.… But if you can find enough common ground, you can get something done,” she said. “You can solve a problem. You can accomplish a goal.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.