L.A. schools to reopen Wednesday; threat against schools was ‘not credible,’ officials say

Students return to school a day after a threat that closed all LAUSD campuses was determined not credible.

- Share via

A crudely written email threat to members of the Los Angeles Board of Education prompted officials to close all 900 schools in the nation’s second-largest school system Tuesday, sending parents from San Pedro to Pacoima scrambling to find day care — while New York law enforcement dismissed a nearly identical threat from the same sender as an obvious hoax.

The unprecedented districtwide shutdown reflected the tense atmosphere over possible terrorist attacks less than two weeks after two Islamic radicals opened fire at a workplace party in San Bernardino, killing 14.

L.A. Unified School District Supt. Ramon Cortines said he made the decision to order the school closures because he couldn’t take a chance with the system’s 640,000 students.

By evening, school officials said they had inspected all campuses and that the FBI had discredited the threat.

“We believe that our schools are safe and we can reopen schools in Los Angeles Unified School District tomorrow morning,” school board President Steve Zimmer said in an evening news conference.

L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti and Police Chief Charlie Beck defended the decision to close the schools, saying investigators did not know at the time whether the threat was legitimate.

“I think it’s irresponsible … to criticize that decision at that point,” Beck said. “Southern California has been through a lot in the past few weeks. Should we put our children through the same thing?”

He said the email included all Los Angeles Unified schools and mentioned explosive devices, “assault rifles and machine pistols.”

“These are obviously things we take very seriously,” Beck said.

The district called and texted parents early Tuesday morning to alert them that schools would be closed — the first systemwide closure since the Northridge earthquake in 1994.

Although the school district could technically be subject to a loss of $29 million in per-pupil funding for closing campuses, state Supt. of Public Instruction Tom Torlakson said that he is certain the district would not be docked those funds.

Alan Glasband, a substitute teacher at San Pedro High School, said he and several other instructors had not received notifications. He said he heard about the bomb threat through a text from a friend.

Another friend, he said, had driven from his home in Norwalk to Orville Wright Middle School near Los Angeles International Airport before he heard the news.

“I’m pretty distraught that they didn’t bother to tell us,” Glasband said.

By midday, elected officials briefed by law enforcement said the threat did not appear to be credible.

Rep. Brad Sherman (D-Los Angeles), a senior member of the House Foreign Affairs committee, said the email lacked “the feel of the way the jihadists usually write.”

Sherman said the roughly 350-word message did not capitalize Allah in one instance, nor did it cite a Koranic verse. He said the elements of the threatened attack also seemed unlikely, such as the claim that it would involve 32 people with nerve gas.

“There isn’t a person on the street who couldn’t have written this,” with a basic level of knowledge of Islam, Sherman said. “Everybody in Nebraska could have written this.”

Still, he added, the person did have a knowledge of Southern California, and the threat could not be immediately discredited.

“I don’t know whether this was sent by a radical Islamic jihadist or somebody who had an anti-Islamic agenda or just a prankster,” Sherman said.

The FBI is working to determine where the email originated and who wrote it. Officials said it was routed through Germany but probably came from somewhere closer.

District officials and law enforcement worked since at least 10 p.m. Monday to decide how to respond to the email, police sources said. Cortines, who is retiring from the school system, told The Times that he was notified at 5 a.m.

All members of the Board of Education were alerted of the threat in an email sent at about 3 a.m. from L.A. School Police Chief Steven K. Zipperman, according to a district source.

One or more board members already were aware of the threat, including Zimmer, who was a recipient of the email.

New York officials received the email at roughly the same time, and with three hours less time to assess it, came to a sharply different decision.

Mayor Bill de Blasio said the threat was “so generic, so outlandish” that it couldn’t be taken seriously.

“It would be a huge disservice to our nation to close down our school system,” De Blasio said.

The mayor went so far as to suggest whoever wrote the threat was a fan of the cable television show “Homeland.”

New York Police Department Commissioner Bill Bratton said “we cannot allow ourselves to raise levels of fear. Certainly raise levels of awareness. But this is not a credible threat.”

Brian Levin, a former NYPD officer and director of the Center for the Study of Hate & Extremism at Cal State San Bernardino, said that while “it makes sense to err on the side of safety,” there is a drawback in doing so.

“When a closure like this takes place, unfortunately it will embolden others to try it again.”

At least one group largely celebrated the district closure: students, many of whom were scheduled for final exams in this last week of classes before winter break.

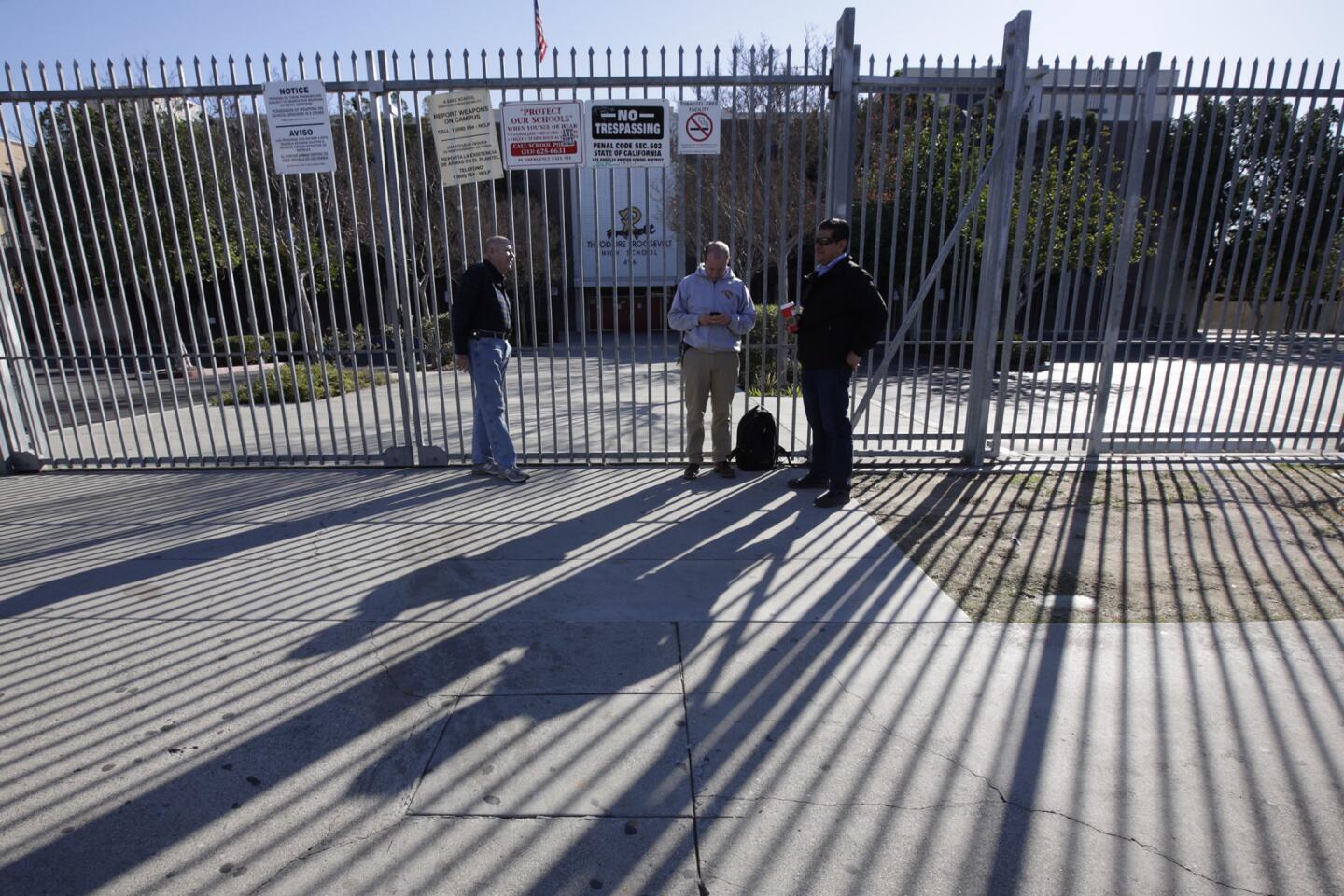

Alexis Diaz, a senior at Roosevelt High in Boyle Heights, and his little brother glided by the deserted campus on hoverboards.

His cousin had called him early to tell him that school was canceled. Diaz didn’t believe him, but he turned on the news and saw that it was true.

“I thought, well, that’s good because I have finals,” he said. “I was ready for the AP Spanish test, but not history.”

Michael Ramirez, 18, skateboarded down the middle of Cypress Avenue in Northeast Los Angeles, popping wheelies and blasting music into white ear buds.

He had been on the way to Lincoln High School when a friend texted that there was no school.

“He said, ‘ISIS or something,’ “ Ramirez recalled.

“I’m kinda tired of hearing all this ISIS,” he said. “It’s annoying. I’ve got finals. But I guess it’s good to take control. Better safe than sorry.”

His plan for the unexpected day off: “Get with some friends; maybe go hit downtown.”

Parents had to rush to find someone to watch younger students, and coped with fears about terrorism that seemed a lot more realistic since the attack in San Bernardino.

Sarah Nichols of Echo Park decided to keep her three elementary school-age children with her for the day.

“I would prefer for them to be with me under the circumstances,” Nichols said.

She didn’t want to explain to them what terrorism was, what kind of danger might have awaited. She just told them it “wasn’t safe to go to school today.”

“I didn’t go into detail because I didn’t want their little minds to wonder,” she said.

Los Angeles Times staff writers Joe Mozingo, Ruben Vives, Joseph Serna, Joy Resmovits, Bob Sipchen and Sarah Wire contributed to this report.

Hoy: Léa esta historia en español

MORE ON THE LAUSD CLOSURES:

L.A. schools threat disrupts many people’s daily routines

L.A. defends response to threat that New York dismissed as a hoax

With Los Angeles schools back open, families can expect to see more police

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.