Must Reads: L.A. County deputies stopped thousands of innocent Latinos on the 5 Freeway in hopes of their next drug bust

- Share via

The team of Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies cruises the 5 Freeway, stopping motorists on the Grapevine in search of cars carrying drugs.

They’ve worked the mountain pass in Southern California since 2012 and boast a large haul: more than a ton of methamphetamine, 2 tons of marijuana, 600 pounds of cocaine, millions of dollars in suspected drug money and more than 1,000 arrests.

But behind those impressive numbers are some troubling ones.

More than two-thirds of the drivers pulled over by the Domestic Highway Enforcement Team were Latino, according to a Times analysis of Sheriff’s Department data. And sheriff’s deputies searched the vehicles of more than 3,500 drivers who turned out to have no drugs or other illegal items, the analysis found. The overwhelming majority of those were Latino.

Several of the team’s big drug busts have been dismissed in federal court as the credibility of some deputies came under fire and judges ruled that deputies violated the rights of motorists by conducting unconstitutional searches.

The Times analyzed data from every traffic stop recorded by the team from 2012 through the end of last year — more than 9,000 stops in all — and reviewed records from hundreds of court cases. Among its findings:

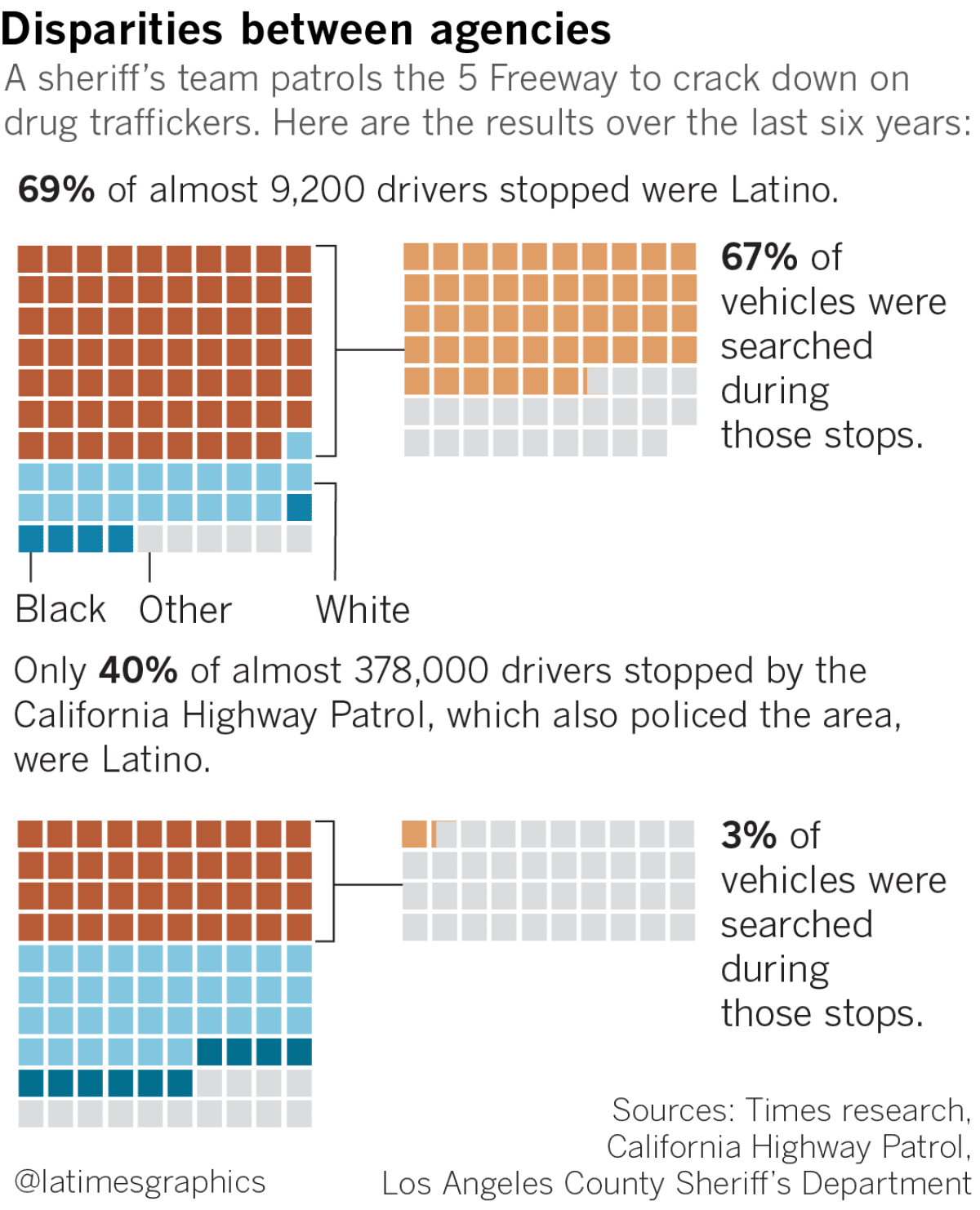

- Latino drivers accounted for 69% of the deputies’ stops. Officers from the California Highway Patrol, mainly policing traffic violations on the same section of freeway, pulled over nearly 378,000 motorists during the same period; 40% of them were Latino.

- Two-thirds of Latinos who were pulled over by the Sheriff’s Department team had their vehicles searched, while cars belonging to all other drivers were searched less than half the time.

- Three-quarters of the team’s searches came after deputies asked motorists for consent rather than having evidence of criminal behavior. Several legal scholars said such a high rate of requests for consent is concerning because people typically feel pressured to allow a search or are unaware they can refuse.

- Though Latinos were much more likely to be searched, deputies found drugs or other illegal items in their vehicles at a rate that was not significantly higher than that of black or white drivers.

How a team of L.A. County sheriff’s deputies stops Latino drivers at a disproportionate rate

The L.A. County Sheriff’s Department said that racial profiling “plays no role” in the deputies’ work and that they base their stops only on a person’s driving and other impartial factors.

“The [team] has removed tens of millions of dollars’ worth of illegal narcotics from circulation, including heroin, methamphetamine, cocaine and fentanyl,” the department said in a statement responding to The Times’ analysis. “A recent arrest involved the seizure of approximately 10,000 Oxycodone tablets, a small dent in the opioid addiction crisis that has enveloped our nation.”

A Sheriff’s Department spokeswoman declined interview requests to discuss The Times’ specific findings. The department would not say whether it has conducted its own analysis of the deputies’ stops.

Sheriff’s Department officials said the team was launched as a response to a spate of drug overdoses in the Santa Clarita area. Similar units operate around the country as part of a federal program designed to use local and federal law enforcement agencies to combat drug trafficking.

In December, Sheriff Jim McDonnell heaped praise on the team, ticking off its accomplishments in a lengthy statement. “The importance of this mission cannot be overstated,” the sheriff said.

But several legal and law enforcement experts said the department’s own records strongly suggest the deputies are violating the civil rights of Latinos by racially profiling, whether intentionally or not.

“When they say, ‘We’re getting all these drugs out of here,’ they are not taking into account the cost,” said David Harris, a law professor at the University of Pittsburgh who studies racial profiling by police. “They are sacrificing their own legitimacy in the community as a whole and the Latino community in particular.”

Kimberly Fuentes, research director for the California League of United Latin American Citizens, described The Times’ findings as “extremely disturbing and troubling” and said the advocacy organization would demand a meeting with Sheriff’s Department officials.

“These findings risk tarnishing any trust between the Sheriff’s Department and the Latino community,” Fuentes said.

On Thursday, after The Times published its findings, McDonnell released a statement saying he was proud of the team’s work but also “concerned about any allegation of racial and ethnic profiling.” He said he takes “very seriously questions about race and police procedures” and would work with the county’s inspector general “to examine any issues of concern.”

‘Looking for a defeated expression’

On a recent morning, Deputy John Leitelt wound his way up the Grapevine.

The shift had been uneventful. Leitelt had stopped several vehicles, but he quickly cut the drivers loose after exchanging a few words and seeing nothing suspicious.

He had spent an extra few minutes with a Latina motorist he stopped for an expired registration. When Leitelt learned she was traveling to Fresno to visit a friend, he asked where she would be staying. When she said she hadn’t yet made a reservation, he would say afterward, he was suspicious.

He asked whether he could squeeze a large stuffed toy dog sitting in the passenger seat. She agreed, and Leitelt then asked whether he could look in the trunk. Inside was a small suitcase, and Leitelt decided she was telling the truth. He thanked the woman and let her go.

Later, Leitelt explained that he carefully studies a motorist’s reaction when he asks for permission to search their car. “I’m looking for a defeated expression,” he said.

Leitelt, a deputy for 18 years, joined the highway team at its start. He and the team’s three other deputies — all white men — typically work alone in marked SUVs. Their terrain spans the roughly 40 miles of freeway from the border with Kern County to just south of Santa Clarita.

“If we search everyone just because as cops we think we have carte blanche and have authority over people, then we’ve lost our way.”

— L.A. County Sheriff's Deputy John Leitelt

Though the deputies are looking for any criminal, nearly all of the arrests are for drug-related crimes. The 5 Freeway, they say, is a pipeline for cartels to move drugs up the West Coast and return to Mexico with cash from drug sales as well as weapons purchased in the U.S.

Although The Times’ review of department data shows that 74% of the drivers he pulls over are Latino, Leitelt said race or ethnicity does not influence whom he chooses to stop.

“I’m not looking for people from Mexico — not at all,” he said. “I’m looking for people who are driving a certain way…. If we search everyone just because as cops we think we have carte blanche and have authority over people, then we’ve lost our way.”

He later declined to comment on The Times’ analysis of the team’s stops.

In deciding whom to stop, Leitelt said, he looks for certain behavior, such as drivers traveling at or below the speed limit and then hitting the brakes when they see his cruiser. He also tirelessly “kills plates” — cop jargon for running license plate numbers through a state law enforcement database on his in-car computer. Cars with expired registrations, a man driving alone in a car registered to a woman, or an older car with a recent registration will get closer attention, he said.

Once he sees a car he believes is worth checking out, Leitelt needs a valid reason to make a stop. That can include any minor traffic violation, such as speeding or crossing a lane line without signaling.

To prolong a stop and continue questioning a driver, Leitelt and other law enforcement officers need reasonable suspicion that a crime is being committed, a legal bar that the U.S. Supreme Court defined as something more than a hunch.

They can search a vehicle if the driver gives permission. Otherwise, an officer needs probable cause — where the facts and circumstances indicate a crime is being committed. The smell of an illegal drug, a weapon lying on a seat or a police dog outside the car signaling the scent of drugs inside can be enough.

As he was on his way back to the station at the end of his shift, Leitelt noticed an old Volkswagen Beetle struggling up a hill in the middle lane. The deputy drove up alongside the car and saw a young Latino-looking man behind the wheel.

The deputy dropped back and slid in behind the car. Tapping the California plate into his laptop, he saw the vehicle had new license plates and was recently registered to someone who lived several hours north. Leitelt noticed the windshield was cracked — a violation of the state’s vehicle code and legal justification to stop the car.

The man, who said he spoke no English, explained in Spanish he was driving slowly because the car’s engine was old and “didn’t have any heart.” He said he worked in California and was making his way to Mexico to visit his young daughters.

The man seemed fidgety and nervous to Leitelt. With traffic zooming by, the deputy instructed him to get out and walked him to the back of the Volkswagen. Leitelt asked in Spanish whether he was carrying methamphetamine. Heroin? Cocaine? Marijuana? A large amount of cash?

The man repeatedly said no, and his voice and expression remained unchanged — usually a sign, the deputy said later, that someone is being truthful. But Leitelt also thought the man was avoiding eye contact, which he interpreted as an indication of possible deception.

Leitelt and another member of the highway team did a quick pat-down of the man’s clothes for weapons and then put him in the back of a patrol SUV.

“He’s super nervous,” Leitelt said.

Leitelt wondered aloud if the driver feared the deputies would ask him about his immigration status. Nonetheless, he pressed ahead, opening the car’s hatch with the man’s key and unzipping his suitcase. Inside were neatly folded clothes, including new dresses for young girls, and some greeting cards.

Thinking the suitcase could be “a prop,” Leitelt kept going. Using an assortment of prying tools, he and the other deputy popped off a section of the dashboard in search of a hidden compartment traffickers sometimes build.

When a density meter dubbed “the Buster” gave an irregular reading on the passenger-side door, Leitelt knocked, peered down into the window well and swung the door open and shut several times before deciding there were no drugs hidden inside. The stop lasted about 15 minutes.

The deputies walked back to the SUV and opened the door.

“OK, adios,” the other deputy told the man, making a shooing gesture with his hand. Without saying a word, the man walked back to his car and drove off.

‘Psychological babble’

Allegations of racial profiling by police are common, but researchers using data on traffic stops say it is difficult to show definitively that officers selectively target one race or ethnicity. In the case of the Sheriff’s Department’s highway team, experts said using the population of L.A. County, which is 48% Latino, as a benchmark would be misleading. Ideally, they said, they would want to know the racial breakdown of all drivers on the particular section of the 5 Freeway.

But the fact that Latinos made up such a smaller percentage of stops by CHP officers along the same stretch strongly indicates that the Sheriff’s Department team was targeting the group, said several racial profiling experts who reviewed The Times’ findings.

“No matter how justified the stops are, this is what we call selective enforcement,” said Jeffrey Fagan, a Columbia Law School professor who was an expert witness for plaintiffs in a federal civil rights lawsuit against the New York Police Department over its now-defunct stop-and-frisk policy.

Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino counties’ sheriff’s departments have similar highway enforcement teams. In response to public records requests, officials in Orange County said the Sheriff’s Department does not collect racial data on traffic stops. The other two agencies refused to release data.

The federal Domestic Highway Enforcement program drew criticism in recent years over concerns that teams were using stops to improperly seize cash and other property from motorists. In California and elsewhere, defense attorneys have challenged stops, arguing that the highway teams overstep constitutional lines.

In 1999, drug searches by a group of CHP officers during traffic stops led to a lawsuit alleging racial profiling of Latino drivers. To settle the claims, the department banned all officers from asking drivers for consent to search vehicles for several years and retrained them on racial biases.

Douglas Wright, executive director of the National Criminal Enforcement Assn., a nonprofit group that provides training to highway teams, described such units as an effective tool for finding drug traffickers. He said they also help deter unsafe driving whether or not they search vehicles and find anything illegal.

His organization, he said, teaches officers to avoid any profiling.

“All races, all genders and all people are capable of committing these crimes … smuggling these drugs, guns, humans,” he said.

Have you been stopped by L.A. County sheriff’s deputies on the Grapevine?

Get in touch with the reporters at [email protected] and [email protected].

Asking drivers for permission to search a vehicle is a commonly used method for police to check for contraband when officers lack the type of evidence that would legally justify a search without a warrant. The U.S. Supreme Court has sanctioned such searches, viewing consent as a straightforward green light from drivers or passengers to proceed unless there is evidence of coercion.

The Times reviewed data from nearly 4,500 searches conducted by the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department’s highway team and found that about 75% were based on consent from drivers or passengers.

A Sheriff’s Department spokeswoman said the agency was “confident that the DHE team appropriately uses consent searches as a recognized investigative tool, in compliance with all applicable legal standards.”

Some legal scholars have raised concerns about police routinely seeking permission to search.

Consent searches “are based on this fiction that people who say yes … are gleefully saying, ‘Yes, officer, I am happy to help,’ and that anyone who doesn’t want to be searched will simply say no,” said Hofstra University law professor Alafair S. Burke. “But, in reality, the average person hears an officer’s request as a command.”

In Rhode Island and New Jersey, police are prohibited from asking for consent to search a car unless they have reasonable suspicion of a crime.

Data for all types of searches by the L.A. County team show that deputies found contraband in 20% of vehicles driven by Latinos. For black drivers, contraband was found 18% of the time; for whites, 16%. Those differences were not significant, according to a regression analysis conducted by The Times.

The Sheriff’s Department’s highway team has run into trouble in federal court, but not because of racial profiling allegations. In nearly two dozen cases filed by U.S. prosecutors, no judge has ruled whether the team is selectively targeting Latinos. Instead, the deputies’ tactics and credibility have come under fire, resulting in 11 cases being dismissed.

In one, attorneys for a man caught with 38 pounds of cocaine and 8 pounds of heroin argued that Deputy Adam Halloran illegally prolonged the stop to grill the driver about whether he was carrying drugs.

U.S. District Judge Robert H. Whaley agreed and warned that the highway team’s practice of frequently seeking consent to search vehicles “imposes an enormous burden on the privacy interests of drivers. Most drivers would be anxious to move on and would fear that a denial of permission to search would indicate something to hide…. Voluntariness of such consent, if given, does not justify the tactic.”

In his ruling, Whaley said the team’s mission seemed certain to lead to more illegal arrests.

“A policy of the police to create a department to make traffic stops only to seek consent or probable cause [for a search] is troubling,” he wrote.

Seven more federal cases were dismissed amid questions over the credibility of one deputy, James Peterson. Defense attorneys questioned the cases against their clients by pointing out that Peterson had been disciplined in the past for misconduct that involved dishonesty and that a federal prosecutor had once raised doubts about Peterson after the deputy changed his account of an arrest.

Peterson was reassigned from the highway team last year.

Defense attorneys have also challenged claims that deputies can tell whether a motorist is concealing drugs by their responses to simple questions.

In an arrest report detailing the seizure of 48 pounds of methamphetamine from a car he stopped, Deputy Michael Vann said the driver handed over his license so quickly it “seemed abnormal, as if he wanted to speed up the traffic stop … as if he were trying to distance himself from me.” The man’s rocking slightly back and forth in his seat, Vann wrote, was possibly “a way for him to release built up nervous energy.”

How we reported this story on the L.A. County Sheriff's Department highway enforcement team »

When the driver, Mario Manjarrez, told Vann he had been visiting family in Los Angeles and pointed toward the city, the deputy saw the gesture as “an anchor point movement,” which he said criminals use to distract officers. In this case, Vann concluded, Manjarrez had been struggling to recall a made-up story about visiting family and pointed toward the city in an attempt to seem more confident.

When the motorist took a step away from the car, the deputy wrote, it was an unconscious attempt at “distancing himself” from what was inside. And the fact that he switched from saying ‘no’ to silently shaking his head when asked if he had methamphetamine or cocaine was reason for Vann to suspect he was carrying the two drugs.

Manjarrez’s lawyer questioned how handing a license over too quickly could be a telltale sign of deception. She noted that Vann claimed in other stops that it was suspicious when drivers were slow and clumsy in handing over their licenses.

And she pointed out that although Vann maintained that Manjarrez’s finger pointing was a sign of a forgotten cover story, the deputy also had said that in other stops he based his suspicions on people who recited their stories too smoothly.

“I have doubts about the magical psychological powers of Deputy Vann.”

— U.S. District Judge Philip S. Gutierrez

Vann argued that each stop was unique and that he had based his suspicion of Manjarrez on all he said and did.

U.S. District Judge Philip S. Gutierrez concluded that Vann’s justifications could make any word or movement grounds for suspicion.

“I have doubts about the magical psychological powers of Deputy Vann,” Gutierrez said at a hearing in November. “To me, it’s psychological babble.”

Prosecutors dismissed the case before the judge issued a ruling on whether Vann’s search of the car was illegal, and Manjarrez went free.

Another man caught with 10 pounds of methamphetamine concealed in a tire was let go after a different judge ruled that Vann violated the man’s constitutional rights when he kept him detained without a valid reason. In a third case, a judge upheld the legality of a drug seizure but found that Vann had violated the driver’s Miranda rights.

Vann, Peterson and Halloran did not respond to a request for comment made through the Sheriff’s Department. The U.S. attorney’s office declined to comment.

Only a small proportion of the arrests made by the highway team result in federal prosecutions, which generally carry stiffer sentences than state charges. In state court, more than 450 people pulled over by the deputies have been convicted of drug transportation and other crimes, according to a Times analysis of court data. About the same number of people arrested were not charged with a crime.

Sheriff’s Department officials who oversee the highway team said in interviews they were unaware that any of the deputies’ arrests had fallen apart in federal court. Sgt. Daniel Peacock, the team’s direct supervisor, said the department no longer sends the team’s cases to the U.S. attorney’s office for review.

Times staff writers Ryan Menezes and Ruben Vives contributed to this report.

Additional credits: Graphics by Swetha Kannan. Produced by Agnus Dei Farrant and Sean Greene. Video edited by Robert Meeks.

Twitter: @joelrubin

Twitter: @bposton

UPDATES:

6:50 p.m.: This article was updated with comments from a statement released by the sheriff.

This article was originally published at 3 a.m.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.