- Share via

This story is part of Image issue 17, “Offering,” a special gift from L.A.’s creative community to a city that seemingly has it all. Read the whole issue here.

We have bumped into each other somewhere, yes? I swear. You look familiar. Where have I seen you before? Meeting an artist can be a disorienting experience — in part, because of how difficult it is to anticipate the paradoxical nature of the encounter. Many times, the work precedes them. You’ve seen the painting. The photo. That sculpture. The body has perfect memory when it comes to energy. You’ve felt something created by someone. What the artist made already hit you. Essentially, the first official “hello” is when you recognize you’ve already made the connection.

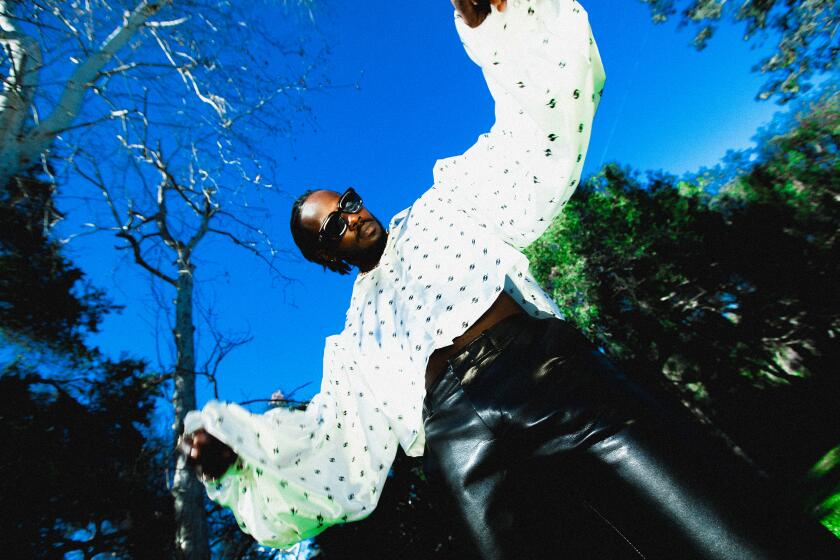

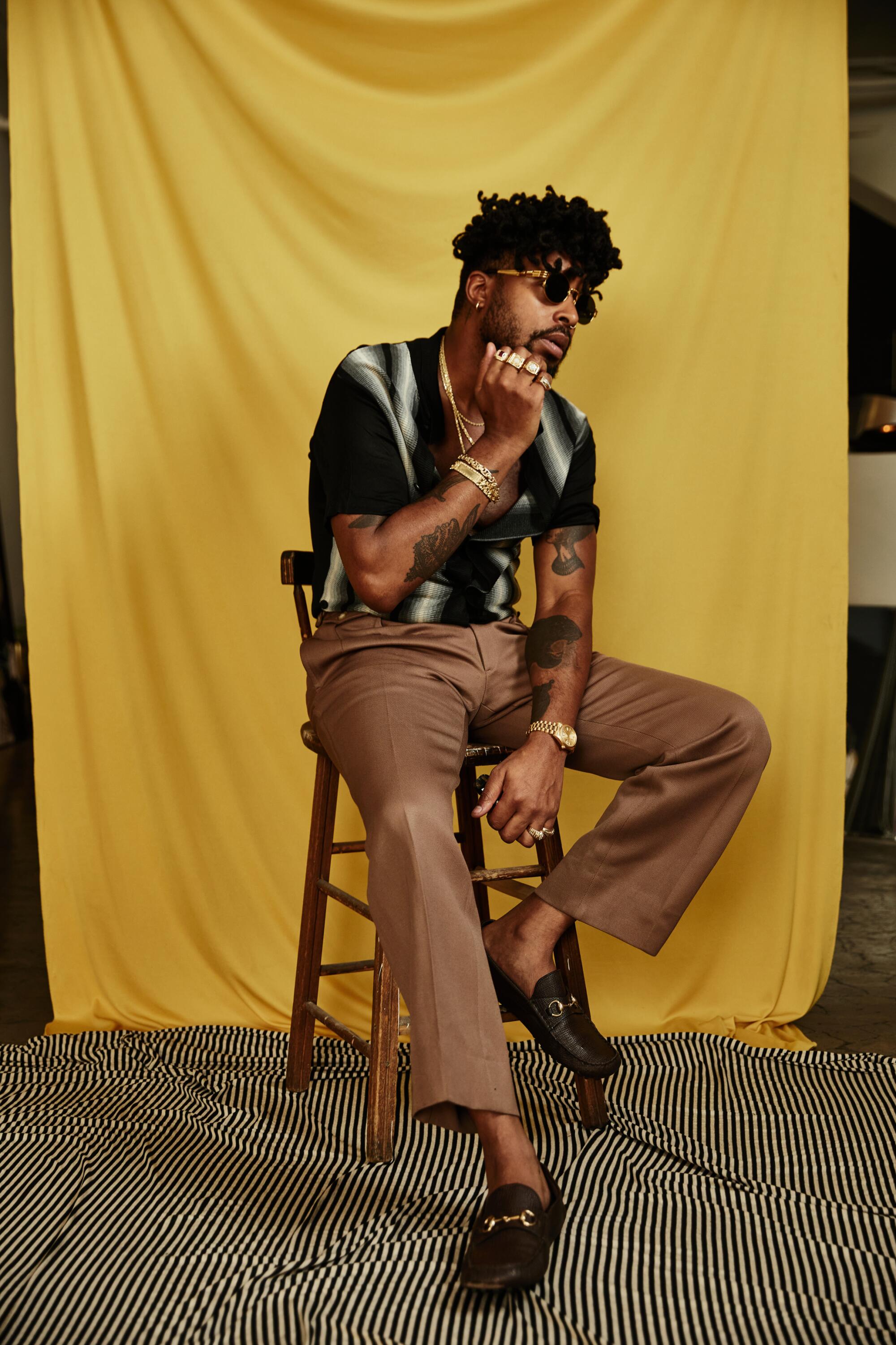

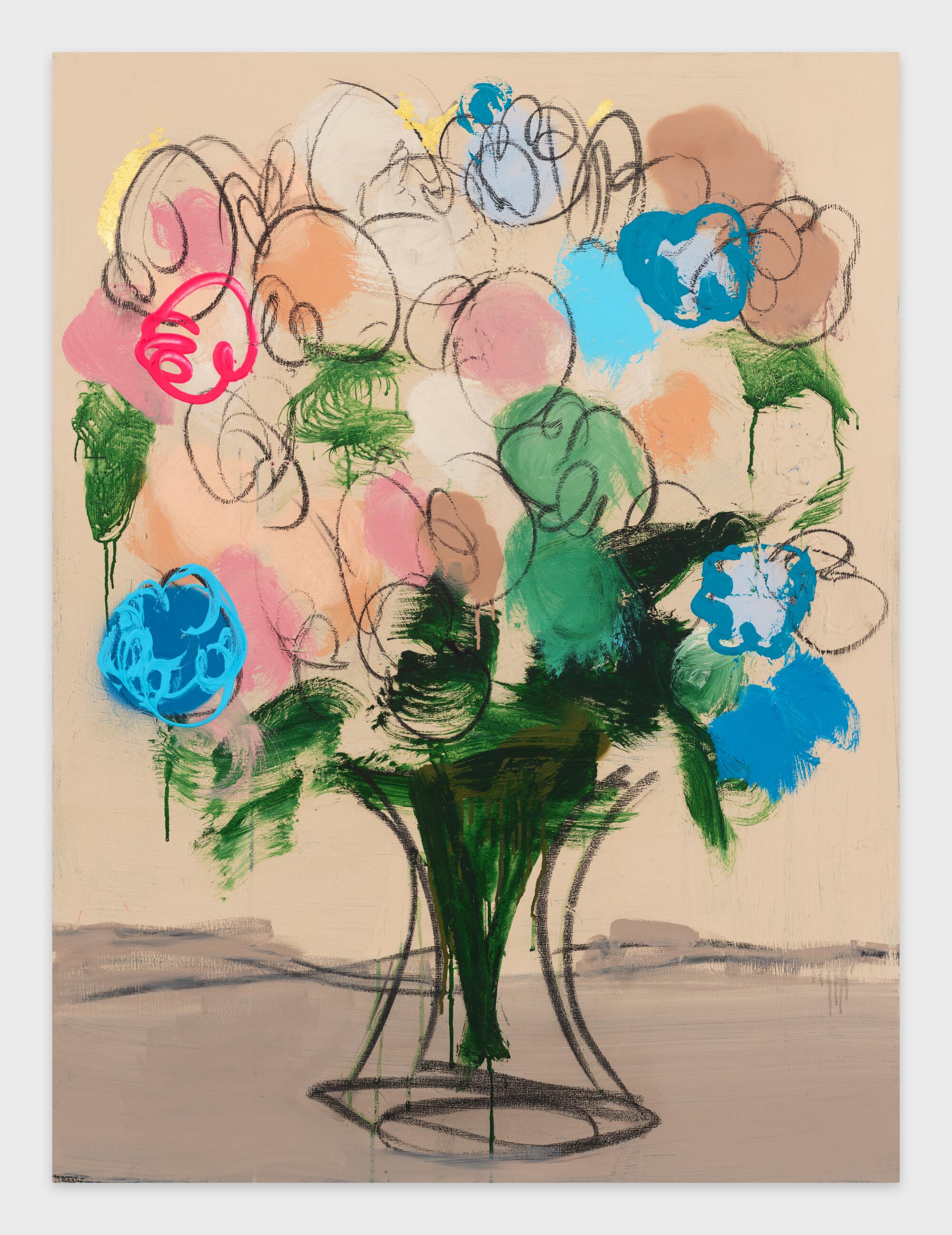

You know a Ferrari Sheppard when you see it. It punctures and wounds the soul with its emotional clarity, then it heals you with its honesty. Which is why, in our first conversation, I couldn’t quite shake the sensation that we were picking up where we’d left off. Sheppard’s voice is one I’ve heard for the better part of a decade. His oeuvre spans disciplines — from Twitter (where he went by Stop Being Famous) to sonic art (as one half of hip-hop group Dec 99th, with Yasiin Bey) to visual art, where his large paintings shift between abstraction and figuration.

On the eve of Frieze L.A., where Sheppard is presenting new work, we spoke about many things — his journey as an artist, the people he’s met (that time at Chateau Marmont with designer Rick Owens), his influences and how abstraction creates space for mystery to bring someone’s human experience more into view.

Ian F. Blair: I’ve been following you for a while, even before I knew you were an artist. I remember you from the Stop Being Famous days on Twitter.

Ferrari Sheppard: It’s crazy. Because I almost want to hide that part of my life. That period I was obviously in my early 20s. In 2010-ish. I’m doing these interviews; I’m interviewing celebrities. I kind of shaped or molded my personality as a journalist around Lester Bangs, who used to write for Rolling Stone. I just loved how cavalier he was. He would ask the hard questions and just get into the real meat and potatoes of what a person is. So, the alter ego of that was me, completely speaking my mind on this platform. I would tweet. It wasn’t purposely controversial. It’s just something that a young man is thinking. This was before the introduction of consequence — you can be dragged for your thoughts, you can be canceled, you’re gonna be eliminated. And I’ll be honest, I didn’t really respect that early on, because I’m just like, “This is a video game, a social experiment.” I viewed it more like an art project than anything.

I was always making art — that was my secret life. And one day I just had this epiphany. I was like, “Dude, what you’re doing is almost like Pablo Picasso being on Jerry Springer. It doesn’t make sense. Why are you doing this?” I find value in tangible things and thoughtful things. You can’t find tweets, you can’t find a viral moment. So, for me, that’s what kind of brought me [to leaving Twitter]. It was also just me maturing. [I’m] closing in on 40, and I know that I want to contribute something greater to society. And I think I saw where social media was heading. It was a pretty dark place, and it wasn’t fun anymore.

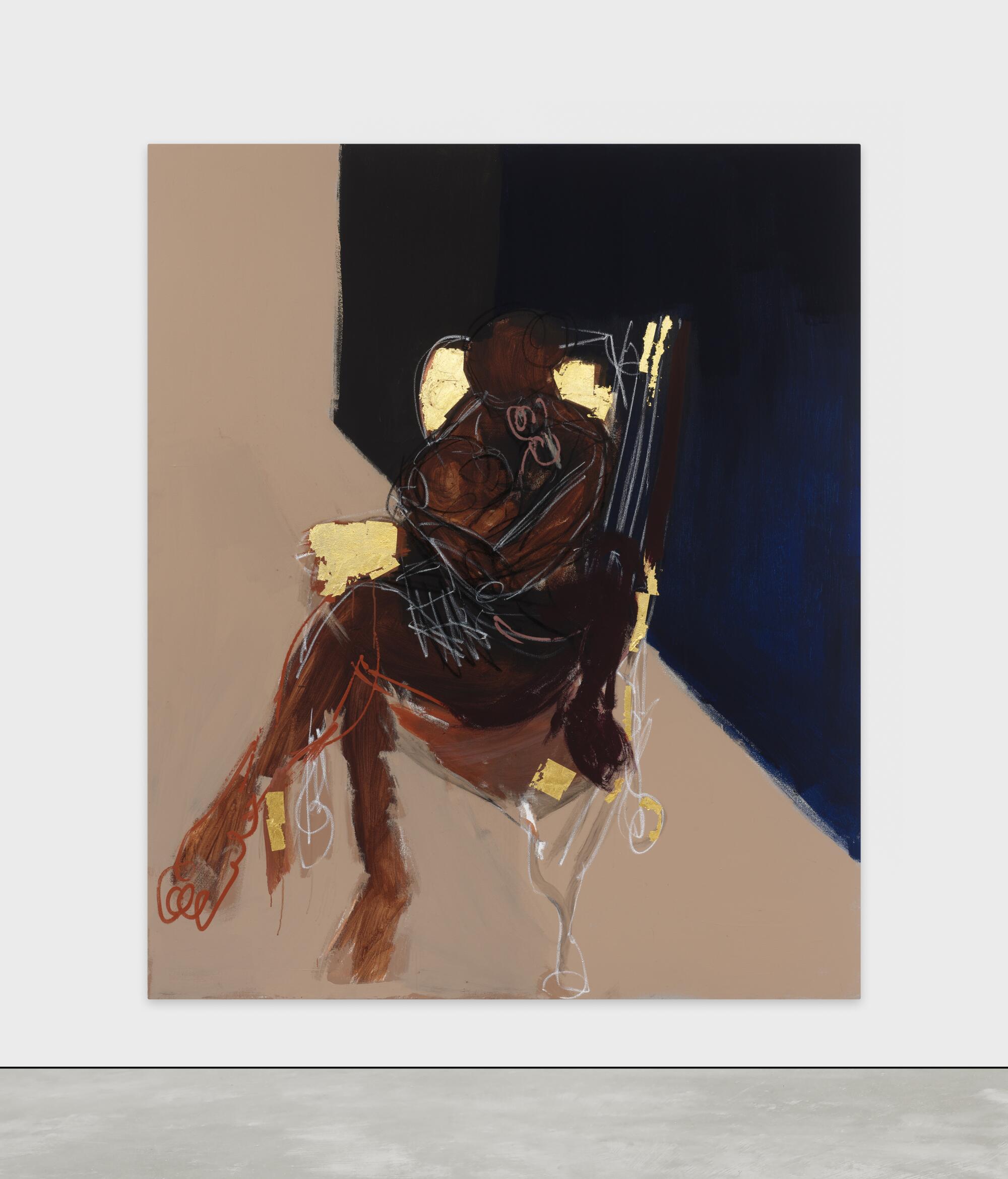

IFB: I went to the UTA show “Positions of Power.” That was the first time I had seen your work in person. One thing that’s hard to see on a screen — but totally jumps out at you in person — is the gold. How did gold first become a part of your practice? Why did you start experimenting with gold?

FS: Gold was an obvious thing for me. If you’ve ever seen any of my first paintings, they were really realistic. I think most artists, that’s the way they start — master anatomy, get the fundamentals down. Then, what eventually happens [is] you become bored with the realistic figure.

In the Renaissance and the earlier European movements, they used this gold leaf. I say, “You’re in the middle of abstraction and figuration, but it’s also very much gestural, loose and explosive. What if [you] threw in something that is familiar?”

The first piece that I tried gold on, I wasn’t careful with the gold at all. I was going over the gold and violating the gold. And I’m like, “There is something to this.” That’s what started my journey.

IFB: Thinking back to that UTA show, you had all these abstract portraits of subjects sitting around this Rick Owens bench in the main room. The interesting thing about that experience was how you communicated a strong desire to play with or think through the role of the gaze.

FS: I take notes while I’m in the studio because I’m always trying to understand why I do things and why I don’t do things. In my notes, I’ve noticed that more than anything, the figures are representative of me. I am exposing myself through my lines, through my compositional decisions and my memories.

Some of my best work is where you could tell — I could tell — it had no inhibitions, that I am feeding you all instinct from my subconscious. With the trust that I understand anatomy, human emotion, things that are left unsaid — all of these things could come through in just a few lines. If I trust myself and I’m true to myself and I’m true to my practice, then the viewer will feel it. I never sit there and think, “What will people think?” Because that is the opposite of what my practice is based on, which is freedom from all of that. I’m free! The only place in this world that can be, or resembles, freedom; I’ve found that in art.

Rick Owens [and] Michèle Lamy volunteered that furniture for that show. One night I met up at Chateau Marmont with Michèle Lamy and Rick came, and I met his mom. His mom was this little Mexican woman, almost looked like my mother. She was just so kind. I think about Rick Owens’ image — people may think he’s like a devil worshiper or whatever. And I’m just like, “He’s an artist.” I saw a reflection of him through me in how he interacted with his mom.

IFB What was that night like?

FS: It was more normal than you would probably think it is. It was just a group of people sitting around talking about world events and fashion and art. For a minute there, I forgot that this was Rick Owens. No one got on top of the table and danced. I meet artists and they’re regular people, man.

IFB: Tell me about the “Dec 99th” project with Yasiin Bey.

FS: Yasiin came to me because I was Stop Being Famous. During that time, it wasn’t odd for me to receive an email from a celebrity who was like, “Who are you? I want to get to know you.” And that’s what he did. We first met in Addis Ababa, in front of the Friendship [International] Hotel. And from then on, we became inseparable.

The album came organically. He heard me playing some of my music. Next thing you know, we had an album. I was really upset about how fans reacted to that work, because I don’t think they gave it a fair shot. It’s bittersweet, because I [saw] the little things on social media — people say that I ruined his career. They were expecting [Yasiin] to be like, when he made “Black on Both Sides.” (He was in his early 20s, man!) He was deep in his spirituality. And I just played the role of facilitator. I said, “Whatever you feel, I’m just trying to complement that.” That’s just where he was, man. And I think that that is beautiful.

At the end of the day, I am pro-artist. That doesn’t mean I am pro-successful artist — someone who is selling a bunch of records or a bunch of paintings or whatever. I am for someone who wants to create instead of destroy, you know, because that to me is beautiful.

IFB: Why do you think people are attracted to creativity?

FS: Because the destruction is so foul. There’s so much destruction and sorrow on Earth. I’m always looking for something that gives me just a little hope. And that’s why I say that the role of the artist is so important. It’s often underappreciated. Everything that an artist makes in his world — whether it’s your Mercedes-Benz, your apartment, fashion, anything that you think of — can take you away from the harsh realities of rent, death and poverty.

It’s obviously important to be rooted in reality — and there are artists who do examine reality. But I don’t think that I’m good at depicting violence and negativity. And that’s OK. We have a spectrum: We have Dr. Seuss and we have Edgar Allan Poe. Edgar Allan Poe could never be Dr. Seuss. Dr. Seuss could never be Edgar Allan Poe. I don’t believe it’s just happy-go-lucky when you look at my paintings, because [there] definitely is pain, but it’s just not overt. There’s violence there. But it’s not overt. Maybe the violence has already occurred, and maybe this is the aftermath of it. Or maybe it’s impending.

IFB: The abstracting of the human form — the facial expressions, the way in which they’re sitting or standing or whatever — opens up a really interesting space that can hold multiple things at the same time. Like multiple emotions, multiple feelings. It seems like there’s a certain level of hope, to use your word, or possibility in that space. How does your practice make room for that kind of emotional space?

FS: I grew up in public housing, bro, during the height of the crack epidemic. My friends was selling crack. And that was normal. We were all disenfranchised. I’ve been shot at five times in my life on different occasions. And it’s just now that I realize — I’m in therapy — how traumatized I am. Some nights, I have night terrors [where] people are trying to kill me. And it’s because that actually happened. It wasn’t until I became an adult that I understood that it’s not normal to be attacked with a gun. Somebody’s shooting at you, trying to kill you. It was some really dark times, so I had to create, within myself, a fortification to survive.

I didn’t have any hope. When people don’t have hope, they don’t care about their surroundings. They don’t care about a lot of things. It’s important to feel that you matter. So, with my art, what you’re probably experiencing is an aspiration and a realization of self. If you see something that is regal about my work, that is what I see us as, or I see myself as. It’s something to aspire to. If you see love in my work, that is a realization that there’s love within us. In fine art, some of those terms that I just used are often viewed as corny or sentimental, because art likes to be clinical. That means you’re intelligent. I disagree; I think that emotional intelligence is just as important as any other thing.

L.A.-based artist Panteha Abareshi speaks to a contradiction: Our bodies are the only things that we have, yet they are not us

IFB: Do you work with live subjects or from photographs?

FS: It’s a blend. I try not to be so dependent on source material. Jack Whitten said it best that photography has influenced visual art in the 20th and 21st centuries more than anything else. It’s easy to just go through a magazine and say, “That figure looks interesting.” I do that sometimes. That figure triggers something that I can build around, maybe their body language. When the work comes from my mind, that’s when photography has failed me. I can’t find anything that anyone else has produced that will inspire me. That’s scary; I always call it the “no man’s land.” Because that’s really me.

IFB: I’m a big fan of Jack Whitten. How do his ideas of abstraction factor into your work?

FS: What attracted me to Jack Whitten were his lectures. I didn’t have a relationship with my father or my grandfather. I always longed for some type of grandfather figure that would help me, assist me, in the way I might view the world. When I listened to Whitten, it brought visual art to a level of sophistication that I had not seen before. He’s elevating visual art to a science. Or even beyond a science into a philosophy — how to see, how to view the world, how to think.

I went to school at the Art Institute [of Chicago], which was heavily conceptual — almost too conceptual for my taste. But at that time, I was in poverty coming from a really horrible situation. I was like, “How do I make money to sustain myself, you guys?” We watched a video in 4-D class with a girl banging her head against a locker for 10 minutes. I’m like, “I can’t relate to this.”

But being introduced to Whitten, I could understand him, because we come from similar backgrounds. Abstraction, with African or Black abstract artists, means so much more to us. We’re always being asked to show our hands — put your hands up, make sure you’re not doing anything. And with abstraction, you could keep your hands behind your back. You can play around, then you present it to the world, and there’s still a mystery there. I think that as a Black man growing up in America, we’re not allowed to have mystery. So that was the first space where I found there can be mystery. That’s what drew me to Jack Whitten.

IFB: How does preserving mystery connect with the vulnerability that you try to present in your work?

FS: If we look at the greatest works of art in any medium, there’s always this opportunity, this invitation, for a loop. And by loop, I mean that the ending is not quite the ending. If you’re writing a movie script or if you’re writing a story, you don’t want the last portion of it — the conclusion — to just say, “And that was it.” That doesn’t live on. Some of the best works of art, you can come back to them 10 years later, 20 years later, 100, 500 years later, and they have different meanings. And they’re still speaking, and they’re talking different languages. [The work is] different, it’s moving, it’s progressing. Other than me seeing the work as a loop, an ouroboros of sorts, I don’t think that there’s any equation to make it where it’s open-ended other than to introduce abstraction.

There are fundamental principles to my practice. And one of the fundamentals that I’ve come to realize is that I can bend the shape, the form, the figure — I can abstract these things, but I cannot abstract human emotion. If I paint something and it makes me sad, it’s f—ing sad. That is the barometer of the life of the piece, so to speak.

There have been times when I’ve made something that is aesthetically pleasing as f—. Like, that’s sexy! That is beautiful! But I’m like, “Something is missing.” A truth, an emotion, a conflict. If I’m having a confused week or month, and I’m not myself, I’m going to create work that is not myself and there’s a certain uneasiness about it. I think that there’s space for art that does that. Some people want that on their wall. I’ve seen some [of that] work — that’s not for me. Like, some awkward stare.

I don’t want to be sentimental. So what I’ll do is I’ll put flaws in it. I’ll introduce flaws to the painting. Flaws that are not contrived but [that] are very much letting you know that a human being made this and I’m not trying to have some glory moment.