Verbal jiujitsu, disarming and other tips for dealing with microaggressions

- Share via

“I was wondering why you don’t have an accent,” U.S. figure skater Mirai Nagasu recalled a parent asking her at a recent meet-and-greet, after asking if she was from California.

Nagasu froze, unsure how to respond.

For the record:

10:15 a.m. June 2, 2021A previous version of this article identified Mindy Hoang as a physician. She is a medical student.

Did the person assume all Asians were recent immigrants? Was it naive ignorance or subtle racism?

The moment passed, but Nagasu continued to dwell on the interaction. As a public figure and role model, she needed to be diplomatic, especially when interacting with kids. But she also felt the need to push back, especially now during the resurgence in anti-Asian hate and xenophobia that left her parents concerned for their safety.

Olympian or not, her experience is all too relatable.

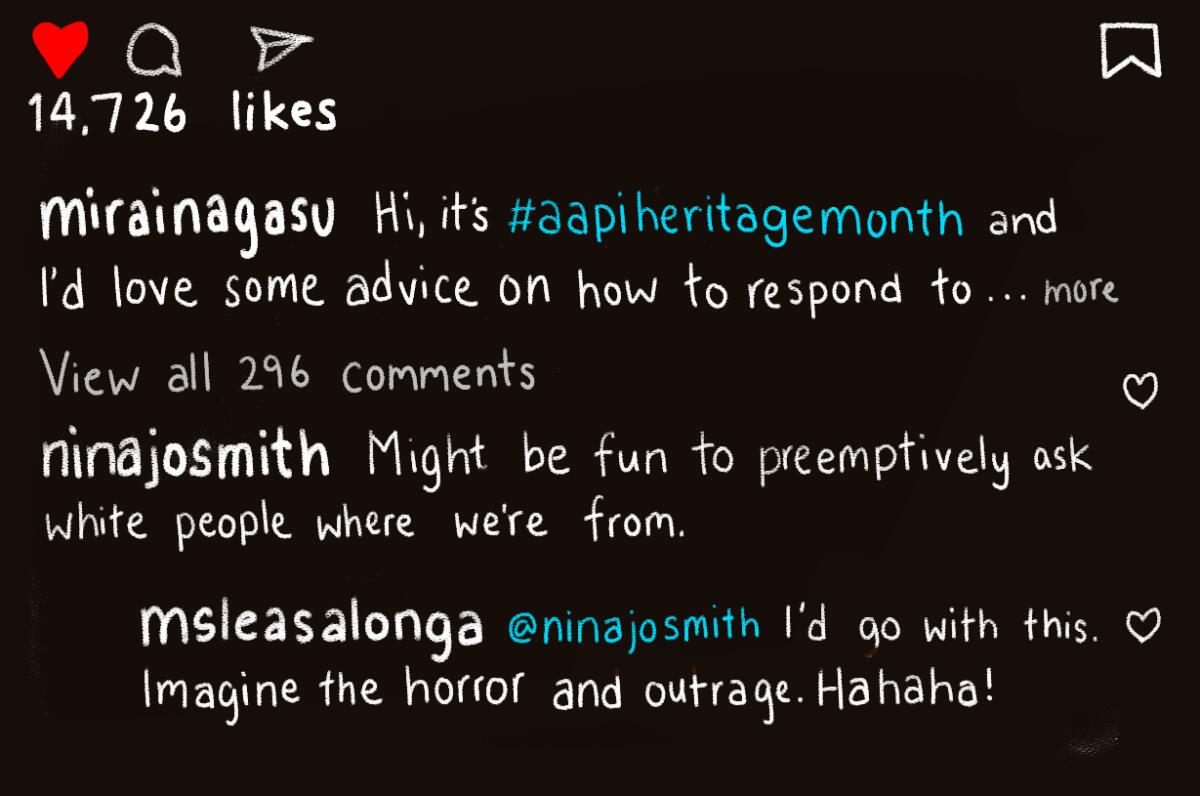

For Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, The Times asked our readers: How have you responded to microaggressions?

One spoke of having to educate co-workers about why a racial slur was offensive. Others shared how frequently they were asked where they’re from or mistaken for other Asians. Another spoke of how they now dread going to work after a colleague shared a yellowface meme and their boss responded “LOL.”

Psychologist Derald Wing Sue calls microaggressions the “everyday slights, indignities, insults, putdowns and invalidations” that people from marginalized communities experience on a regular basis.

Although these affronts often come from well-intentioned people, they are draining and have a “macro impact” on our health and well-being, said Sue, a professor at Columbia University who researches microintervention strategies.

Whether and how we respond to a microaggression is situational, but we don’t have to passively let them happen to us or in front of us. There are ways, large and small, to push back and “signal to both the perpetrator and onlookers that this is unacceptable behavior,” Sue said.

He has four tactics for disarming and dismantling microaggressions:

1. Make the invisible visible.

Because microaggressions are easier to trivialize and brush off than explicit racism, it’s important to acknowledge that it happened. “Making the invisible visible” means pointing out the underlying message within the microaggression.

When people compliment Sue’s English, they are assuming that he did not grow up in the U.S., which reinforces the stereotype that Asian Americans are perpetual foreigners.

Sue responds, “I hope so. I was born here” or “Thank you. You do too.”

His comeback — “a form of verbal jiujitsu” — undermines the implicit subtext and indicates they said something wrong, without creating a huge amount of defensiveness, Sue said.

2. Disarm and dismantle the microaggression.

Some microaggressions are too harmful to go unchecked, Sue said.

In these cases, Sue recommends tactics that range from deflections that express disapproval to challenging what was said or done.

When someone starts to tell a racist joke, you can cut them off before they can reach the punchline, Sue said. “I know you meant that to be a joke, but that’s not funny.”

Or, say you don’t want to hear it and walk away, Sue said.

By stopping the microaggression in its tracks, you indicate that what they’re saying is offensive and unacceptable, Sue said.

3. Educate the perpetrator.

Depending on your relationship with the microaggressor, you may want to explain why their behavior was harmful, Sue said.

For those conversations, Sue recommends separating the microaggressor’s intent from the impact.

“If you try to argue over intent, it’s a waste of time and energy,” Sue said. “But if you get them to think about impact and the harm, you force the dialogue into your territory.”

Mindy Hoang, a Vietnamese American medical student from Ohio, remembers when an Asian American doctor asked if her parents were fond of gambling and if they worked in a nail salon.

The blatant stereotyping left her feeling stunned and anxious. She lied and said that her mom was a nurse and her father was a manager.

Looking back, she wished she had said, “I don’t think that is an appropriate generalization to make.”

“Next time when someone asks me, I’ll say, ‘Yes, my parents are nail salon workers,’” Hoang said. “‘No, they don’t have advanced degrees, but they are smart, compassionate and they work hard to be able to be the best parents for me and my brothers.’”

4. Seek external reinforcement and support

Given the constant and cumulative nature of microaggressions, it’s important to find outside help, especially if there’s a power imbalance or if pushing back puts you at risk or in danger.

For example, if a teacher or boss doesn’t seem like they’d be receptive to you speaking up, Sue recommends finding allies who have equal-status relationships with the perpetrator to intervene on your behalf.

External support, whether in the moment or afterward, is also important.

When Sue’s research team studied racial microaggressions within classroom dynamics, they noticed that after a teacher said or did something inappropriate, the students of color would make eye contact with each other.

“That’s nonverbal microintervention support,” he said. “What they are saying is, ‘We’re with you. That really happened. Don’t buy into that stereotype they have of you.’”

Salvin Chahal — a Los Angeles-based Punjabi Sikh performer and producer — said people often follow him in their cars during his walks, disrespect him in grocery stores or don’t bother to acknowledge his presence.

But even when he gets frustrated, he stops himself from publicly expressing his anger. As a South Asian man with a beard, he doesn’t want to put himself in danger.

Instead, he calls up his Sikh American friends who can relate.

“When dealing with microaggressions, I allow myself to process the emotions when I am in a safe place,” he said. “I remind myself of the power I come from, which can never be taken away from me.”

Nagasu said she is still figuring out how she wants to respond to microaggressions, but she’s found ways to use her platform to be an ally to young skaters who might not be able to speak up for themselves yet.

Recently, Nagasu intervened when a well-meaning choreographer was pressuring the young Japanese American skater she coaches to compete to a song from Disney’s “Mulan.”

“My little student was like, ‘I’m not Chinese. This does not reflect who I am,’” said Nagasu.

Nagasu stepped in and let her student choose her music for her next program — from figure skating anime “Yuri on Ice” — and created all-new choreography for her.

Her student’s enthusiasm for skating soared.

“It makes me happy in a giggly way that I’m able to influence the younger generation in a way that was different [than it was] for me,” she said.

More tips from Derald Wing Sue on how to respond to microaggressions

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.