After the Rodney King beating, LAPD’s Foothill Division was ordered to reinvent itself

- Share via

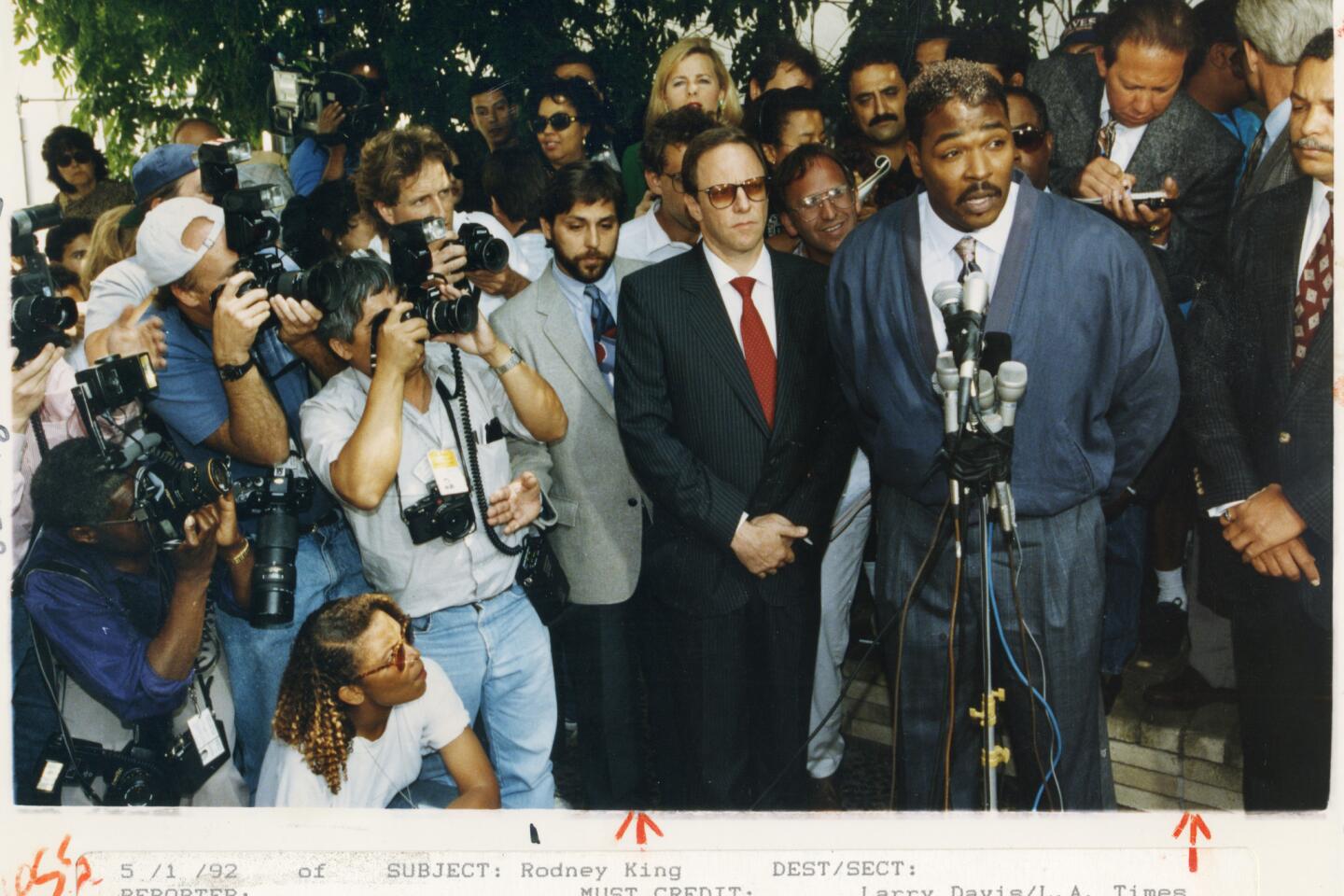

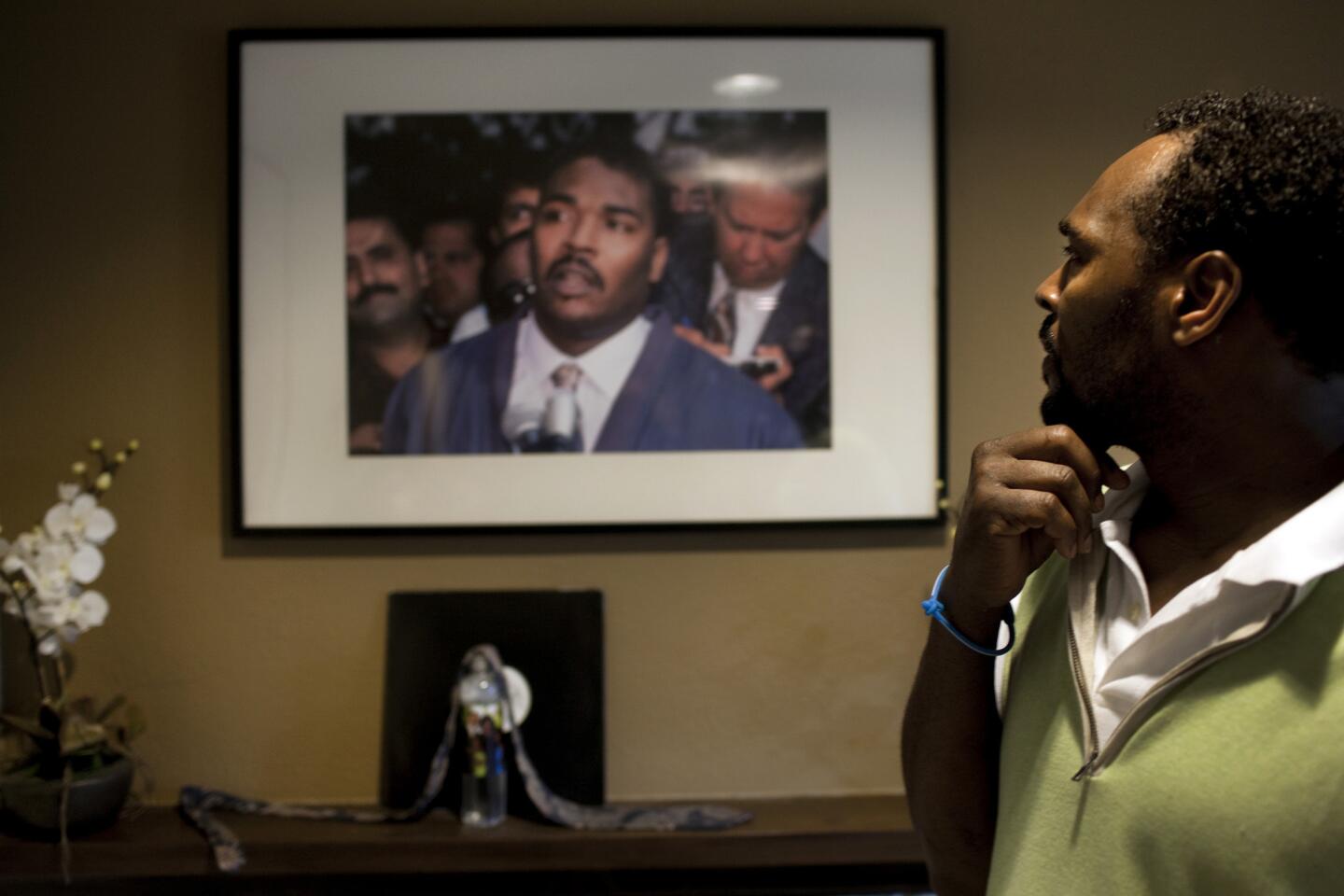

It changed Los Angeles and forced a nation to again confront the issues of racism and police brutality. To African Americans, the videotaped images of police officers pummeling a black man was see-it-for-yourself proof of the street justice they had long complained about receiving at the hands of the Los Angeles Police Department. For once, they weren’t ignored.

With outrage extending all the way to the White House, Los Angeles first reeled, and then demanded reform. Police Chief Daryl F. Gates was pushed out. Mayor Tom Bradley decided against seeking reelection.

But the most lasting institutional effects of the Rodney King beating reverberated within the LAPD, and the shock waves hit hardest in the division where the beating took place: Foothill.

The department--as proud as the Marine Corps but marred by charges of brutality and racism--was told to heal itself. The medicine didn’t go down easily, as much of the department closed ranks around the four officers criminally charged in the March 3, 1991, beating. At Foothill, the FBI dispatched scores of agents to interview officers about misconduct and racial bias. “It was pure hell around here,” recalls William Caughey, a station detective. “It’s a memory of an ugly time.”

Capt. Kenneth Garner, the station’s commander now, likens the situation to the LAPD’s latest headache: “Foothill back then was Rampart today.”

It was an unlikely place for the epicenter. Unlike 77th Street or Southeast, two of the city’s most violent police precincts, Foothill was a place of fewer crimes and fewer allegations of racism. But almost overnight, Foothill became the proving ground for a new kind of LAPD--one with a little less swagger, and one that promised to work in partnership with the public it serves.

Ten years after the beating, the changes wrought by it are evident here: A division once dominated by white males, many of them military veterans, is now headed by an African American and has more women and minority group members throughout its ranks. People who go to the station to report a crime will find officers at the front desk who are both polite and efficient, and a cop who speaks Spanish is never far away. Residents and business owners have a community police advisory board, a formal means to help set the division’s priorities.

Those measures may seem small to people accustomed to a friendly hometown police force, but for the LAPD--known best for its combat-ready SWAT teams, its “Blue Thunder” airships and its aggressive anti-gang units--the changes are significant.

And yet, some things haven’t changed. Young black men in Foothill say police still stop and question them on the street when they’ve done nothing wrong. And no matter how much the community clamors for crackdowns on everyday ills such as graffiti and truancy, violent crime remains the division’s priority. Today’s cops say, “Please” and “Thank you,” but they still carry guns and cruise the streets looking for trouble.

Shouldered along the mountains of the Northeast San Fernando Valley, the Foothill Division is a patchwork of distinct communities. There’s Pacoima, with the toughest precincts in the division. The store signs along the boulevards are mostly in Spanish, but African Americans retain key civic leadership roles. A few miles north, up Osborne Street, is Lake View Terrace, where old wood-frame homes with chicken coops adjoin new stucco apartments and where King had his fateful match with the LAPD at the junction of Foothill Boulevard and Osborne. West from there is Sylmar, which retains a few semirural pockets despite steady development. To the east, across the 1920s vintage bridge filmed in “Chinatown,” is Sunland-Tujunga, part middle-class suburb, eclectic mountain hideaway and rundown commercial strip dotted with biker hangouts. At the other end of the division is Mission Hills, straddling Sepulveda Boulevard with its thriving retail district and street prostitutes who linger near the motels like pilot fish.

It’s in Mission Hills, in the community room of a large medical clinic, that the Foothill Division Community Police Advisory Board is meeting on a recent rainy night. Nearly 60 people have packed into the room, filling paper plates from a buffet loaded with chocolate chip cookies, celery, meatballs, cheese, crackers and other snacks. Seated at one of the lunchroom-style tables near the front are Efren and Sylvia Hernandez of Pacoima. Efren, known as “Shorty,” is a retired auto worker renowned for fearlessly patrolling his neighborhood in his car as a kind of a mobile neighborhood watch. Also at the table is Betty Cooper, a white-haired African American woman wearing lavender-tinted glasses and an embroidered sweatshirt. And a table or two away is Joe Lozano, a retired carpenter for the studios, who lives in Mission Hills.

“We have a vested interest in our community,” he says. “I’ve been in my house for almost 40 years.”

Lozano and the others are on the front lines of community policing. The concept, embraced by the LAPD after King in an attempt to shed its image in many communities as an occupying army, is designed to give the public a greater say in law enforcement. The monthly meetings, co-chaired by Capt. Garner and Sylmar anti-graffiti activist Tom Weissbarth, are aimed at letting people tell police the problems they want addressed--which may differ from what the LAPD sees as a priority. Residents want police to stop kids from breaking into homes or spray-painting walls with gang signs--in addition to tackling the more serious issues. But questions of resources keep getting in the way tonight.

Residents pepper new Valley Deputy Chief Ronald Bergmann about the senior lead officers, who are the link between neighborhoods and the police department. Police Chief Bernard C. Parks had ordered these officers to work patrol again, reducing the amount of time they have to spend with citizen concerns. Under pressure, Parks reversed his decision late last year--but it hasn’t been implemented quickly enough to satisfy residents.

Bergmann explains that the LAPD doesn’t have sufficient officers to do everything it used to, and that even popular special programs such as Drug Abuse Resistance Education are in danger.

“Obviously, roll calls are getting smaller and attrition is far above what we are hiring,” Bergmann says. The department, he adds, is doing its best to juggle competing demands--such as fielding patrol cars to respond to crimes in progress.

The group is not entirely satisfied by this answer, and one of the advisory board members complains that he can’t even get his calls returned anymore. Garner cuts in: “If you don’t get a return call, then your next call is to me. I’ve said that since I got here, and that seems to have worked for everyone who has done it.”

Garner, the first African American to run Foothill Division, sees policing in terms of customer service. “I treat this division as if it were a business, and treat the people like customers,” he says. “They’re coming in here because they have a problem--either their car was stolen, or they had a burglary--and the best we can do is be courteous. Treat it like a Nordstrom.”

But Weissbarth says the panel has less of a role today than when he was first named to it shortly after the King beating. Years ago, he says, the panel would be asked to weigh in on such minutiae as the deployment of vice officers. Today, he says, the panel is not consulted on such matters.

He believes Garner and Bergmann are strong supporters of community policing, but says residents and business owners must be prepared to press their demands. “I’ve always felt the most important thing is to remind the commanders of the things that matter to the people who live here,” Weissbarth says. “They spend their whole lives being promoted or demoted based on their record with serious crime. No one gets ahead for their actions on graffiti and truancy.”

Shane Coleman recalls the night LAPD metro officers, working a special assignment in Foothill, pulled his car over. He’s still not exactly sure why. “I guess it was because there were six black males in the car,” Coleman says. “They checked it out, went through the whole thing. The worst they did was make us kneel on the ground.”

Community policing or no, the LAPD remains a magnet for accusations of racism and mistreatment. Much of the criticism revolves around police stopping blacks for questioning, something that’s only supposed to happen when an officer has probable cause, but has happened enough across the United States to touch off a nationwide campaign against racial profiling.

“We are supposed to explain why they are stopped,” Bergmann says. “I suspect we may not always do that.”

Airto Smith, like other African American men in the community, says he has been stopped by police for no reason.

“When I moved out here from Cincinnati and found out that this was the place they beat Rodney King, my No. 1 concern was the police,” says Smith, 26, of Pacoima. “People worry more about police than the gangs. When the police pull you over, you don’t know what’s going to happen.”

Kevin Miller, 22, also says he has been stopped without cause.

“I think it’s all racial--most police are white, and they don’t like black people too much,” he says one day while shooting pool in Pacoima.

Racism was never established as a factor in the King beating itself. But long-standing concerns that racist attitudes infected the department were given new currency following disclosures that Officer Laurence Powell, hours before he turned his baton on King, had sent out a squad-car computer message describing an unrelated spat among African Americans as “Gorillas in the Mist.”

Eager to deploy officers who more closely matched the makeup of the community, the LAPD’s senior brass began transferring Foothill’s white officers, replacing them with African Americans and Latinos. A black captain, Paul Jefferson, was brought in to oversee patrol.

“Out of crisis comes energy for change,” says retired LAPD Cmdr. Tim McBride, the Foothill Station captain at the time of the beating. McBride held on to his job by calling in some chits and championing what would become the LAPD’s new credo: community policing.

To give the station a homier feel, a fish tank and couches were placed in the lobby. (The tank was destroyed in the ’94 Northridge quake.) To give the community a voice, McBride established the civilian advisory board and launched a community relations team that crisscrossed the division. “We probably met with 70,000 people in a space of three, four months,” McBride says. “At the meetings, somewhere along the line I would say, ‘I’m ashamed, and I apologize.’ ”

The station is now younger and more diverse than it was in 1991, when blacks constituted 4% and Latinos 17% of the sworn personnel. Today, their numbers have nearly doubled--7% of those carrying badges are African Americans, and 32% are Latino, according to the LAPD. That’s closer to, though not on par with, the the division’s demographics, which city officials estimate at as much as 60% Latino and 10% to 15% African American.

Recently, a retired detective visited the station, looked around and remarked that the detective squad never had so many secretaries. The women, he was gently told, were detectives.

Police relations with African Americans, especially business people, are generally good today, says Tamika Bridgewater, president of the Sylmar-based San Fernando Valley Black Chamber of Commerce. But she and others say there is a continuing problem with relations with young black men. Others acknowledge that Foothill has its share of serious crime. Says 24-year-old Theo Covington: “It’s a rough neighborhood, so they [police] have to mind their Ps and Qs.”

Officer Don Boon saw it coming. Rushing to the aid of his wounded partner, he saw movement from a bush alongside the house where the sniper had taken cover. As Boon drew his handgun and squeezed off two errant rounds, a bullet fired from the gunman’s scoped AR-15 assault rifle tore into his hip. “It just absolutely spun me around, and it knocked me to the ground,” Boon said. “I tried to get up, but I couldn’t use my legs. I’m just waiting for the next round to hit, cause I know I’m wide open.”

Officer Nick Ramirez, like Boon, a Marine Corps veteran, raced to his side to pull him out of danger. “He kept saying, ‘Get up, Marine! Goddamn it, Marine, get up!’ ” Boon recalled.

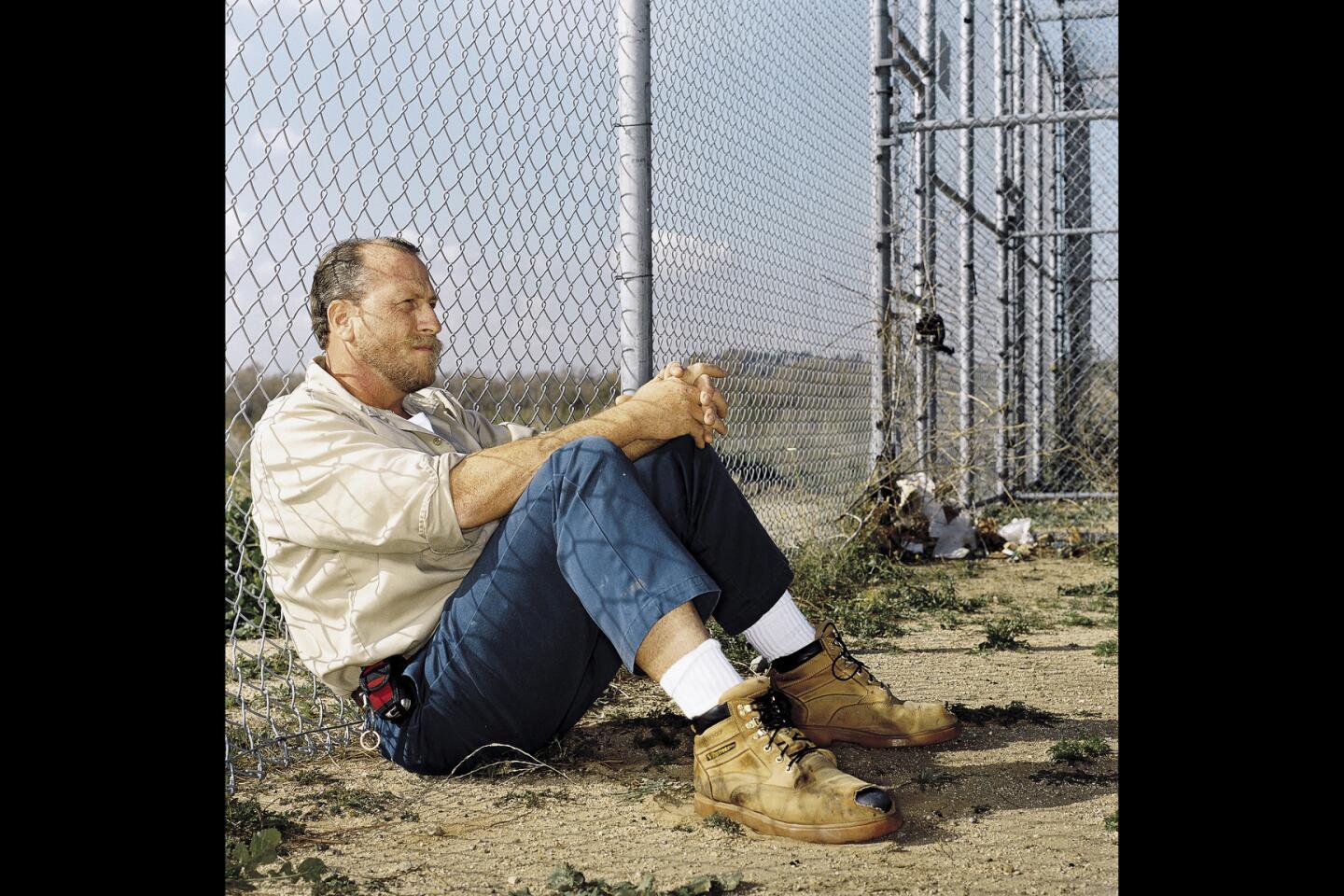

Boon’s limp, which slows him even today, more than three years since the Jan. 15, 1998, shooting by a disturbed man on Kathyann Street in Lake View Terrace, is a reminder that police work also takes place in the street, not just in neighborhood watch meetings. Yet, Boon remains a believer in community policing.

“A big part of our job is finding out from the community what’s going on--who are the problem children causing trouble in the neighborhood. You’ve got to talk to people. You get it from the guy out watering his lawn. You can’t do police work without the community.

“You can go from radio call to radio call to radio call. That doesn’t do us any good if we don’t know what the residents are going through--kids breaking into houses, graffiti,” he says.

“If you are not community-minded at Foothill Division, you don’t stay there,” says Vicky Bass Edwards, a civilian who operates the police-supported Jeopardy program for troubled youths.

Foothill Sgt. Brian Wendling cruises the division and pauses near the site of the beating. Change has been rough, he says, but ultimately good. “Rodney King was not the problem. If the outcome of the arrest is that the video makes us look bad, then, OK, we have to change the way we do things. Going after someone with a stick--that’s a caveman weapon.”

Ten years ago, Sgt. Glenn Younger was one of the African American officers who volunteered to transfer to Foothill to help restore the department’s tarnished image. “Officers felt that everything that happened to Rodney King was justified,” says Younger, who now works in the LAPD’s community-relations department downtown. “I said, ‘How could you justify it?’

“It was something that woke up the whole department. It forced us to a higher accountability level. It opened up the eyes of a lot of individuals. It was a good thing for the department. Something that was overdue.

“Too bad we couldn’t have caught it ourselves.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.