Gas company warned of possible well failure when it sought a rate hike in 2014

- Share via

In 2014, Southern California Gas Co. asked state officials for a rate hike to pay for an ambitious, “highly proactive” safety program to test all 229 of its active natural gas injection wells “before they result in unsafe conditions.”

Wells in four storage fields — including its Aliso Canyon facility near Porter Ranch — were deteriorating, the utility warned, and had been leaking more frequently since 2008. The wells posed a risk of “uncontrolled” failure.

The rate hike request is still pending, and along with it, the safety program.

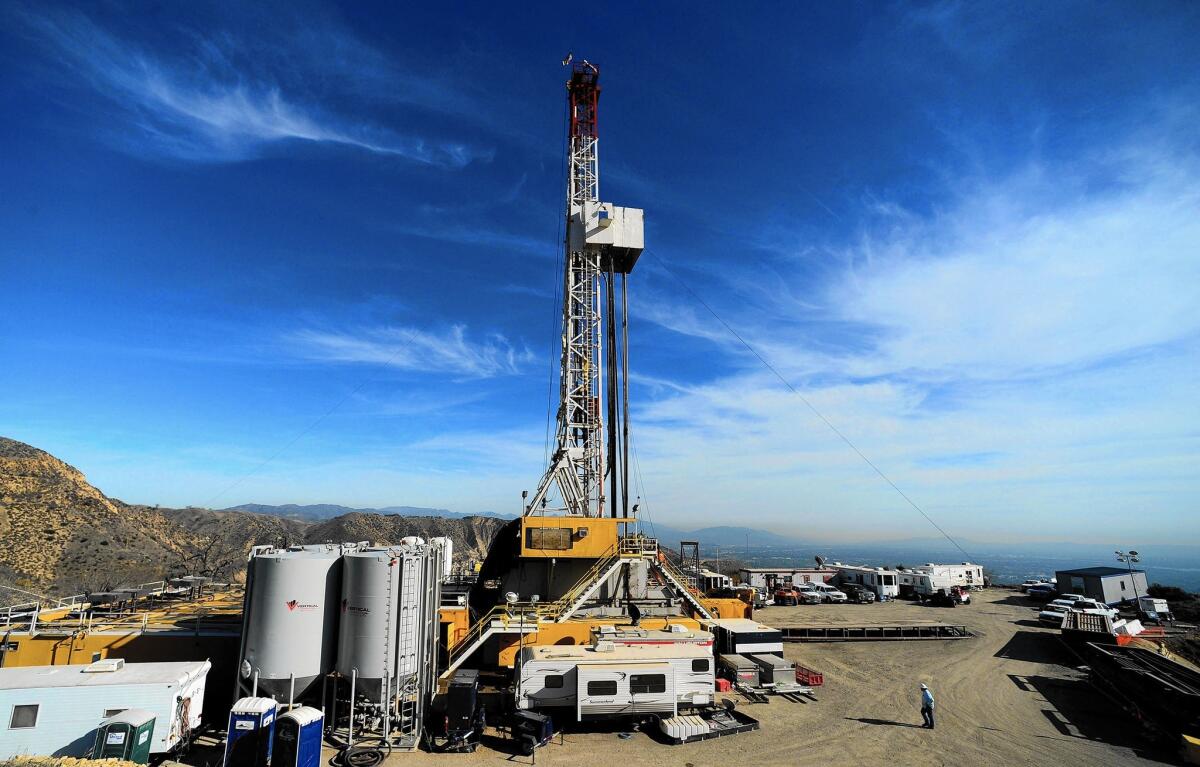

In the interim, the gas company’s warning came true: The failure of one of the Aliso Canyon wells in October released an estimated 5.4 billion cubic feet of natural gas containing methane and noxious odorants.

The leak forced the evacuation of thousands of residents, the closing of schools and emergency regulations requiring testing of all gas storage wells statewide. The leaking well was capped last month, clearing the way for some residents to begin the move back.

Investigators are now trying to determine the cause of the underground blowout and whether anything could have been done to avoid it.

But a Times review of state records shows that before and after Southern California Gas asked for the rate hike to pay for a safety program, it was boosting production of its wells in ways some experts say increased the risk of failure.

In proposing the rate hike to the state Public Utilities Commission two years ago, Southern California Gas officials said the company was repairing leaks in older wells only as they happened. A rate increase, they said, was needed to fund a sweeping $236-million program that included extensive inspections of wells before they leaked, abandonment of wells that failed and the drilling of new wells to replace them.

It remains unclear whether Southern California Gas took any steps to begin that program before the Porter Ranch leak. Gas company officials said the company began testing some wells but have not said how many. State records show the gas company sought permits for tests of Aliso Canyon wells in December, after the leak began.

The PUC and the Office of Ratepayer Advocates, which champions consumers’ interests, said the company had an obligation to deal with the failure risk when it was discovered years ago, rather than wait for a rate increase.

“If SoCalGas thinks there is a safety risk of any kind, they are obligated to mitigate the risk immediately,” PUC spokeswoman Terrie Prosper said. “They do not need to wait for CPUC authorization.”

Mark Pocta, who manages the natural gas division at the Office of Ratepayer Advocates, said the utility should have begun checking aging wells ahead of the start of the preventive maintenance program it outlined along with its rate hike request.

“You don’t need to call it a program,” Pocta said. “You just need to do the work.”

Southern California Gas operates four underground storage facilities in what were once oil fields, including Aliso Canyon. Wells designed and built to pump oil were converted in the 1970s to inject gas at high pressure into the porous oil sands a mile or more below ground. Gas piped in from elsewhere is stored there and withdrawn for distribution to core customers and wholesale markets when prices rise or demand spikes.

Permit records and utility filings show the most troubled wells at Aliso Canyon are the older ones. More than 40 of the 115 still in use were drilled more than half a century ago.

Industry experts and former gas company engineers told The Times the wells deteriorate with age and use. They said outer steel casings typically corrode from exposure to salty brine, or are blasted thin from sand drawn up along with the high-pressure gas. The cement that seals the pipe from surrounding rock can also crack, allowing gas to escape.

Industry experts say pressure readings filed with the state suggest that Southern California Gas may have increased the risk of failure by the method it used to boost the wells’ production.

In addition to pumping gas from below ground through the narrow inner pipes of wells, commonly less than 3 inches in diameter, the utility also drew gas through the larger outer casings of those wells, typically 7 inches wide.

Experts said using the outer casing of a well to increase productivity creates problems in several ways. It accelerates damage and increases the risk that a leak will contaminate groundwater or reach the surface. The narrower production pipes are intended for such wear and are easily replaced; outer casings are permanent fixtures of a well and more difficult to fix when they go bad. In addition, the outer casing provides a safety barrier, “almost like a double-hull tanker,” says Dan Hill, chairman of the Texas A&M Energy Institute.

Engineers who worked with Southern California Gas confirmed the practice. The utility did not respond to questions regarding the extent that the practice was used, and it remains unclear whether the practice played a role in the leak.

In the wake of the leak, a panel of experts formed by state regulators has recommended that regulators forbid the practice of pumping gas through outer casings at Aliso Canyon. New draft rules by the state also would require gas storage operators to inspect not just production pipes but also outer casings for corrosion.

At the same time that Southern California Gas sought a rate increase to improve safety, it moved forward on a $210-million construction project — still underway — to sharply increase the ability to put gas into storage. In that effort, the utility is installing powerful turbine compressors that boost the amount of gas that can be compressed for injection in a single day at Aliso Canyon, with most of the capacity allotted to wholesale customers. Company officials said the project would not increase the pressures that wells are subjected to.

State files on more than 110 company wells in Aliso Canyon and other fields show that Southern California Gas commonly kept wells with damaged casings in operation by using cement patches, metal sleeves or inner liners.

Production reports show Southern California Gas generally injects gas into the fields through newer wells and withdraws it through older ones. However, four wells drilled as long ago as 1941 were used extensively to do both, according to an analysis of monthly well activity data obtained from the state. Those data show these older wells were among the top gas producers in Aliso Canyon. Several experts, including a former gas company engineer, said the practice stresses the steel casings of a well.

State Department of Conservation files contain no record of integrity or pressure tests conducted on any of those four wells after 2008. One of them is Standard Sesnon 25, the well that began leaking in October. Its last pressure test was in 2006, and its last structural integrity test was in 1991.

All the Aliso Canyon wells had annual temperature surveys, which can identify wells already leaking. But of the 15 Aliso Canyon wells drilled before 1946, according to state records, only three had been inspected or pressure-tested in the last three years — at least one of them because it had begun to leak. None of the rest had been inspected or pressure-tested since at least 2006.

Mitch Findlay, president of a company that performed well tests for Southern California Gas from the 1980s through the early 1990s, said inspections to look for problems before leaks occurred were frequent during that period but slowed in the early ‘90s. A single casing inspection, he said, can cost several hundred thousand dollars. He said the temperature and pressure readings, like those the company currently takes, only detect gas already escaping.

After the leak began in October, California regulators ordered Southern California Gas to suspend injections into the field.

Regulators issued an emergency order March 4 requiring the gas company to perform pressure tests and casing inspections of any wells to be put back into use. The order also prohibits the use of well casings for pumping gas.

ALSO

Pluto is defying scientists’ expectations in so many ways

UC Merced attacker was inspired by Islamic State, FBI says

Worker dies after falling 53 stories from downtown L.A. high-rise

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.