Not only China’s wealthy want to study in America

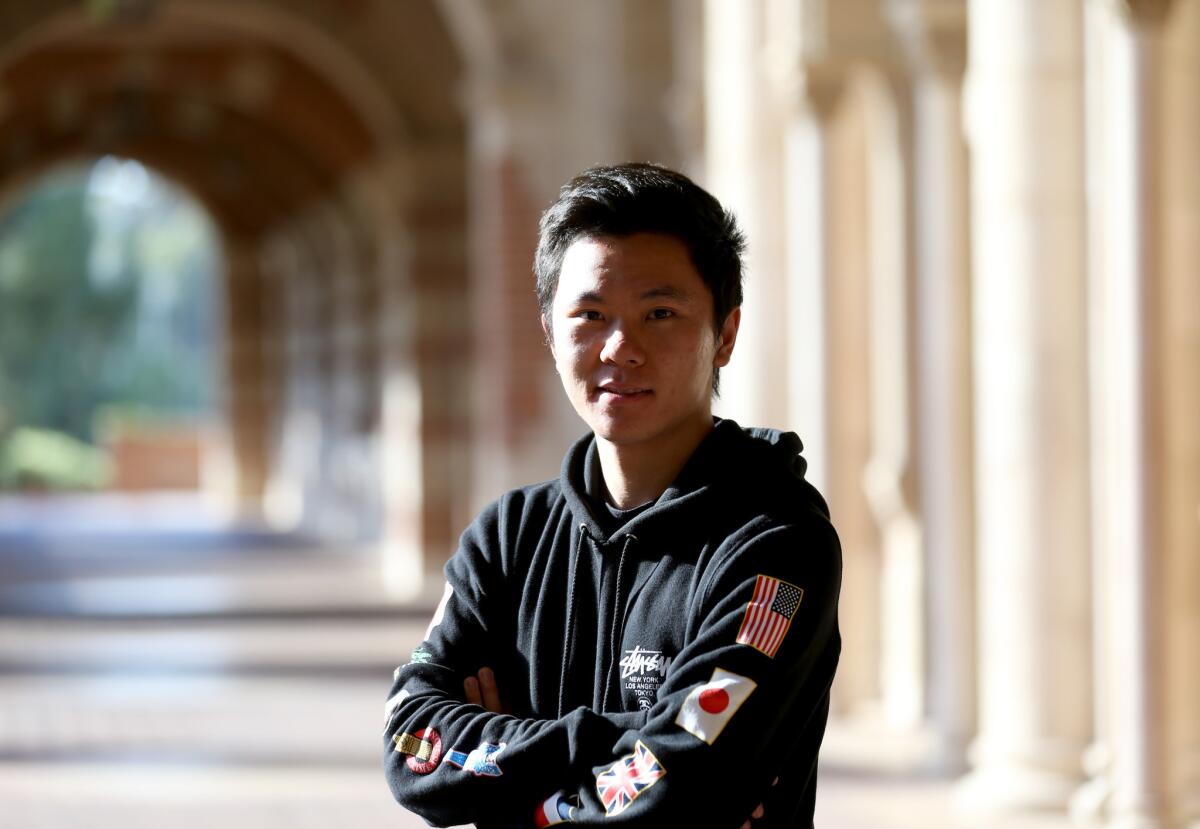

Lantian Xiang, 22, came to the U.S. from China’s Hunan province five years ago and enrolled at Pasadena City College before transferring to UCLA.

- Share via

Three months before the gaokao, China’s all-or-nothing college entrance exam that can determine whether students become cashiers or CEOs, Kenny Fu was having second thoughts.

His parents, small-business owners, wanted him to study in the U.S, but Fu’s English was poor and he was afraid he wouldn’t be able to make friends.

With the two-day, 10-hour exam looming, he hated the idea of a single test determining his path. The family scraped together money to move him to the United States in 2011.

After studying English for a year, he began to attend classes at Pasadena City College, where he volunteers part time and hopes to transfer to UCLA.

More than 124,000 Chinese undergraduates are studying in the United States, according to the Institute of International Education. Many are affluent, announcing their presence on campus with Lamborghinis, flashy clothes and the profligate spending that is the hallmark of the fuerdai — the derogatory term for sons and daughters of China’s new wealthy class.

But a growing number are like Fu — children from lower middle-class families who are looking for an alternative to an overcrowded and unforgiving Chinese educational system.

It is a stereotype that all Chinese students are rich and have Benzes and Bentleys. It’s just not true. It’s just that the rich students show off more.

— Amy Yan, assistant director of the international student center at Pasadena City College

In 2007, just 2,500 Chinese students were enrolled at U.S. community colleges, which have become increasingly attractive to low-income or low-performing Chinese students who want to escape the pressure of the gaokao. Now more than 16,200, or 13% of all Chinese undergraduates in the U.S., are studying at community colleges in this country.

Los Angeles’ community colleges host a large percentage of those students, according to a Los Angeles County Economic Development Corp. report issued in 2014. Nearly half of the 20,000 students from China studying in Los Angeles County attended community colleges, according to the report. Santa Monica College, home to the most international students of any community college campus in the nation, has more than 1,000 Chinese international students — up from roughly 200 six years ago, according to Denise Kinsella, associate dean for international education.

In China, a huge industry of intermediary agencies guarantees acceptance letters for a few thousand dollars, and they’ve successfully marketed American community colleges as a stop on the way to a degree at a four-year university.

“It used to be that only the top students could come to the U.S.,” said Michael Wan, chief executive of the Irvine-based Wenmei Education Consulting Group. “Now, anybody with money can come.”

The trend — a reflection of China’s growing middle class — is eagerly embraced by California’s cash-poor community colleges, which lost nearly $1 billion during the recession. But larger numbers of Chinese students with limited resources or skills will challenge community colleges, which have fewer staff and resources to devote to foreign students.

Some in academia question whether community colleges can handle the influx of Chinese students.

“The number of students is growing much faster than the services for them are,” Wan said.

For every fuerdai who shows up with unimaginable wealth, there are several students who are struggling financially, said Amy Yan, assistant director of the international student center at Pasadena City College.

“It is a stereotype that all Chinese students are rich and have Benzes and Bentleys. It’s just not true. It’s just that the rich students show off more,” said Yan, who came to the U.S. decades ago as an international student herself.

The rising numbers of foreign students in publicly funded universities has irked some parents and legislators. Earlier this year, the UC regents voted to cap the number of out-of-state and international students at UCLA and UC Berkeley at their current levels — about 30%.

Supporters counter with a litany of benefits foreign students provide. NAFSA, an international education professional organization, estimated the total of almost 1 million foreign students in the U.S. contributed $30.5 billion to the U.S. economy last year.

At Pasadena City College, international students pay about $8,000 in tuition a year and generate more than $8 million in revenue. Only a small portion of that goes back into the international student program, said Russell Frank, the college’s interim associate dean of international students. The rest, he said, “funds faculty, programs and students across campus.”

But it’s not just the money, Frank said. A larger international student body gives community colleges a chance to make global connections and expose local students to different cultures.

At Mt. San Antonio College in Walnut — popular because its in the midst of the San Gabriel Valley’s large Chinese population — enrollment of Chinese students has increased from just 27 students in 2005 to 316 last year.

The community college has added several staffers to its international student center, including a full-time international student counselor who can speak Mandarin, said Audrey Yamagata-Noji, vice president of student services.

The biggest challenge, administrators say, is integrating international students into the student body at large — that means getting Chinese students to participate in clubs and make friends with local students.

Chinese students in U.S. universities and colleges are unusually isolated by language and culture, said Zoe Wu, professor of Chinese at Pasadena City College. Typical undergraduate struggles, such as how to register for classes and maintain degree progress, are especially complicated when you add visa requirements and immigration restrictions to the mix.

Chinese students are more likely to ask one another or engage an Chinese-speaking education agent for help than talk to a college administrator, which sometimes causes more problems than it solves, Frank said. For example, agents might be receiving all of a student’s mail and preventing colleges from communicating with them.

Experts say the number of Chinese students at community colleges is likely to increase.

“It used to be that Chinese kids want to go to Harvard, but now there are Chinese students at every level and type of U.S. institution,” said Peggy Blumenthal, senior advisor to the president of the Institute for International Education. “More and more Chinese students are interested in the way America teaches.”

And community colleges, Blumenthal said, offer something that teenagers of any nationality crave: the freedom to be indecisive and the ability to change your mind.

Lantian Xiang, the only son of two white-collar workers from the Hunan province, came to the U.S. five years ago with ambitions similar to that of any American millennial.

“I wanted to have an experience in a foreign country, and I wanted to figure out what my heart wanted,” said Xiang, 22.

His mother suggested he study in the U.S. after she attended one of the many U.S. education seminars put on by Chinese education consultancies, and he embraced the idea. The pressure of the gaokao was stifling, and he wanted to experience what he termed the American lifestyle. He ended up at Pasadena City College.

“People here have their own attitudes, their own thoughts, their own likes,” said Xiang, now a third-year financial actuarial mathematics major at UCLA. “They just follow their heart and don’t listen to what someone tells them to do. That’s what I wanted.”

Twitter: @frankshyong

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.