‘I left my tacos on the table and took off running.’ Immigrants remember the workplace raids of the 1980s

- Share via

Sara Saravia arrived in the United States in 1981 and quickly got a piece of advice: watch out for the men in uniforms. If they catch you, Saravia was told, you’ll find yourself back in El Salvador.

One afternoon, she sat in a restaurant when three men walked in. They wore uniforms. Saravia bolted.

“I left my tacos on the table and took off running,” she said, remembering that she ran so suddenly and so far that she didn’t realize she was fleeing from security guards, not immigration agents.

As she peeled an orange outside of her apartment in Boyle Heights, the 77-year-old Saravia, now a U.S. citizen, shuddered at the memory.

“You felt so afraid,” she said, “you couldn’t even walk to the market.”

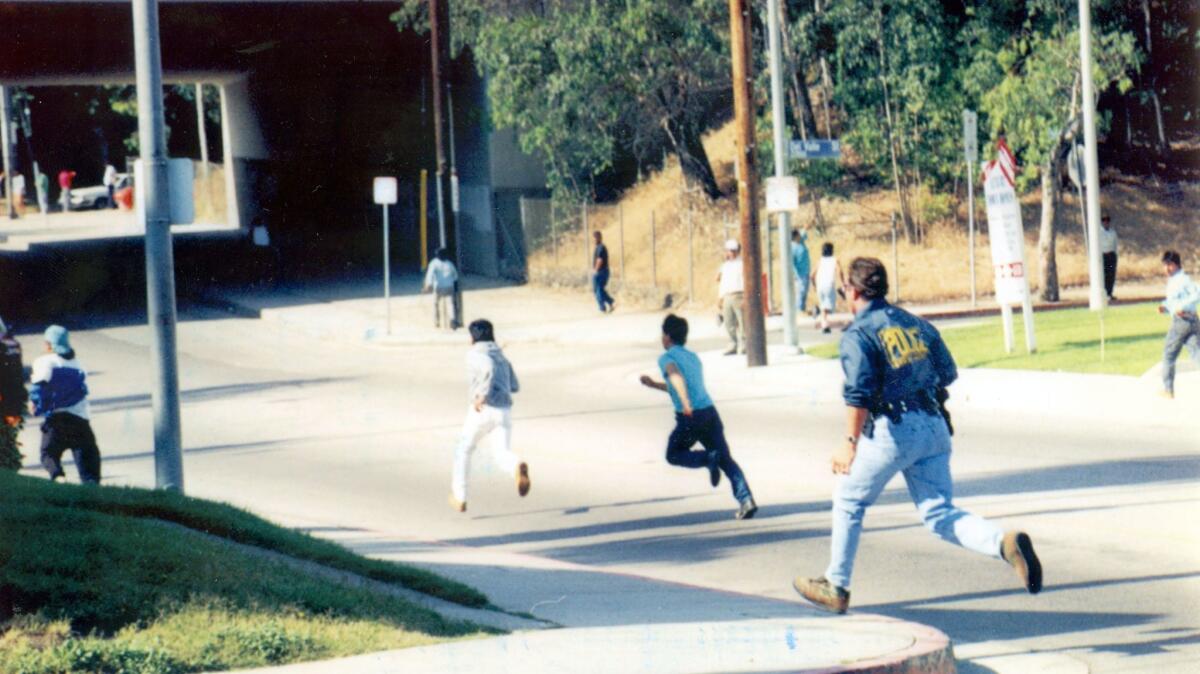

In the 1980s, the federal government launched aggressive immigration raids in Mexican and Central American communities in Los Angeles. Raids were carried out at homes; bus stops, nightclubs, vast agricultural fields and warehouses. They were so frequent that, for many immigrants in the country illegally, their children and other Latinos, it became a fact of life.

The raids inspired everything from art to movies, such as the 1987 comedy film “Born in East L.A.,” written and directed by its lead actor, Richard “Cheech” Marin.

“I remember how normal it was,” Marin said of the roundups. “They were happening all around, and you were reading about it in the newspapers all the time.”

Now comes the impending presidency of Donald Trump, who staked much of his campaign on promises of being tough on illegal immigration and rallied large, boisterous crowds of supporters with those vows.

Trump has promised to deport people here illegally but has not yet provided specifics of his plans. Some of his advisers have said workplace raids are likely to be part of Trump’s crackdown.

The president-elect’s tough talk has won praise from some who believe illegal immigration is harmful to the country and takes away jobs from citizens.

But it has sparked anxiety in places like Southern California with large populations of undocumented workers.

“I think right now there’s lot of fear and uncertainty about how Trump is going to implement the policies that he promised to carry out when he was running as a candidate,” said Angela Sanbrano, founder and former director of CARECEN, a nonprofit organization that provides legal services to immigrants. She said some fear he “may bring back all those terrifying moments and feelings of being afraid of the police and ICE [Immigration and Customs Enforcement].”

The workplace raids became a searing symbol of the get-tough policies of a different era, mostly notably Proposition 187, the California ballot measure that banned immigrants here illegally from receiving many public services.

Over the last 20 years, the tensions eased. Federal officials reduced workplace raids, in part after criticism from business groups and immigration activists. Both the George W. Bush and Obama administrations focused on new tactics, such as forcing employers to fire workers here illegally.

Trump has promised to build a wall on the border and make Mexico pay for it. During a Republican debate, he hailed the Eisenhower administration effort known by the outdated, racist name “Operation Wetback”— as a model for a “deportation force” he said could remove 11 million immigrants living in the country illegally.

Trump has since said the U.S. will pay for the wall and seek reimbursement from Mexico. He reduced the number of deportable immigrants to about 3 million, mostly those with criminal backgrounds — a number that experts say is far higher than the actual number of immigrants in the country illegally with criminal records.

Trump said he wants to triple the number of ICE agents, expand Border Patrol stations and terminate two amnesty programs ushered under the Obama Administration.

Claude Arnold, former special agent in charge of Homeland Security investigations in Los Angeles, said he believes work site enforcement will increase under Trump.

“The majority of people come to the U.S. for work opportunity. It’s a magnet that brings them here,” he said.

Jessica Vaughan, director of Policy Studies for the Center for Immigration Studies, which advocates restricting immigration, said she doesn’t “think we’re going to see people being randomly picked up at bus stops or grocery stores.”

“It’s more likely that immigration enforcement will return to what it was like from 2007-2011, when ICE had stepped-up immigration enforcement and received a lot of funding from congress to boost operations,” she added.

Perhaps no other state would be more affected by the incoming administration immigration policies than California, where more than 2.3 million immigrants who entered the country illegally or overstayed their visas are located, according to the Pew Research Center, a nonpartisan think tank. Texas has the second-largest population.

California’s past hard views of illegal immigration have softened over the years. Since Trump’s election victory, mayors and police chiefs in San Francisco, Oakland, Los Angeles have vowed to uphold policies supportive of immigrants without legal status.

In 2015, Gov. Jerry Brown signed immigration-related measures that included one that removed the word “alien” from the state’s labor code. He also signed legislation allowing noncitizens in high school to serve as election poll workers and protecting the rights of immigrant minors in civil suits. The state also allows people in the country illegally to obtain driver’s licenses.

L.A. is considering legalizing the now-common but largely illegal practice of street vending, hoping to avoid misdemeanor convictions that could be used to deport people.

State legislators are already preparing for a showdown with Trump, hiring former U.S. Atty. Gen. Eric Holder Jr. as an outside counsel to advise on the state’s legal strategy toward the incoming administration.

Joe Del Bosque, a 67-year-old from the Merced County city of Los Banos who farms in Firebaugh, Calif., said he has vivid memories of the raids that happened in the cantaloupe farms he used to help manage in the 1970s and 80s.

A small federal government plane would fly overhead looking for work crews, he said. Soon, green-colored vans would follow. Workers would panic, scatter and run. Farms would lose fruit because they didn’t have enough people to pick.

“INS would come with their vans and circle the fields and then capture as many as they could,” Del Bosque said.

Ultimately, he said, the raids appeared to be more of a show, with immigrants dropped just across the border. Many returned within a few days, Del Bosque said, recalling a time when it was easier to cross the border.

In the more than 30 years since he started his own farm, Del Bosque said, he’s never been subject to an immigration workplace-enforcement operation. A labor shortage has forced him to not care about the background of the people who are hired as long as they can satisfy the legal requirements of filling out I-9 and W4 forms.

“We do everything legally,” he said. “If they can provide us with the documents to fill out these documents, then they’ve got a job.”

Marin said “Born in East L.A.” was the product of a different era, when California was a trailblazer of some of the strongest measures — and rhetoric — against immigrants in the country illegally.

He said the idea for the movie came as he sat in his kitchen and read about a local teen who was in the country legally but was accidentally deported. At the same time, Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the USA” was playing on the radio, he said.

Marin made a parody of the song ahead of the film, which became a success.

The film starred Marin as a Mexican-American who spoke no Spanish but was deported to Mexico anyway. Though it was a comedy, Marin said, the film had an underlying truth about it.

“There’s a reason why the movie has endured. It touched on those real emotions and real situations,” Marin said.

In strongly Mexican-American neighborhoods like Boyle Heights and East L.A., children born in the U.S. would often jokingly and suddenly call out to each other “la migra,” a slang term for immigration agents, in mock warning.

Now, many immigrants who lived through the ’80s find themselves remembering their stories of being captured by or narrowly escaping immigration officers.

Pablo Alvarado, director of the National Day Laborer Organizing Network, said he recalled a story of a man at a day laborer site who was in the middle of getting his blood drawn as part of a county HIV test program when immigration officers pulled up in white vans.

“He ripped the needle from his arm and ran,” Alvarado said.

Jesus Aguilar, co-founder of CARECEN, was standing with three other men at a corner street in the Pico-Union area on a January morning in 1981 when LAPD officers approached them.

Aguilar said “they assumed we didn’t have papers.”

And the officers assumed right, he said.

Aguilar said the officers drove him and the others to the immigration center downtown, where he said they were told to sign documents that would expedite their deportations. Aguilar said he never signed.

He said he didn’t want to return to El Salvador, which was roiled by civil war. He had done everything possible to escape it.

“Some people I knew who were Salvadoran and were deported had been assassinated,” Aguilar said, adding that he applied for political asylum to delay his deportation.

“It was the only alternative we could use as defense,” he said.

Until he could post bail, he remained under the custody of immigration officials for nearly a year.

Aguilar’s efforts to delay his deportation eventually allowed him to receive permanent residency after the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986.

Saravia, the Salvadoran immigrant who had abandoned her meal when she mistook security guards for immigration agents, said she calculated her every move until that law passed. She worked as a housekeeper in Beverly Hills because she believed working alongside Latinos increased her chance of getting deported. She took the bus to and from work in the early morning to avoid bus raids, and rarely left her apartment

Maria Jaramillo, 55, said she was only 20 years old when she came to U.S. from Mexico in 1981. Now a U.S. citizen, she said no one told her about the immigration raids until she learned about it on the news. After that, she spent the next five years wondering when immigration officers would storm the factory she worked at in downtown’s garment district.

“They would always come to the factories around there, but for some reason they would never come to mine,” Jaramillo said. “You know, luck was on my side.”

@LATVives

Times staff writer Cindy Carcamo contributed to this report.

MORE ON IMMIGRATION

A changing border: Barricades won’t solve tough new challenges at the Southwest frontier

Dozens of migrants braved jungles, seas and bandits to reach the U.S. Then they were sent home

Traversing the Rio Suchiate: Between Africa and the U.S., an illicit river crossing in Latin America

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.