Column: At Hollister Ranch, homeowners enjoy private beaches — and hefty tax breaks, too

- Share via

For those lucky enough to live at the exclusive Central Coast property known as Hollister Ranch, the benefits are many.

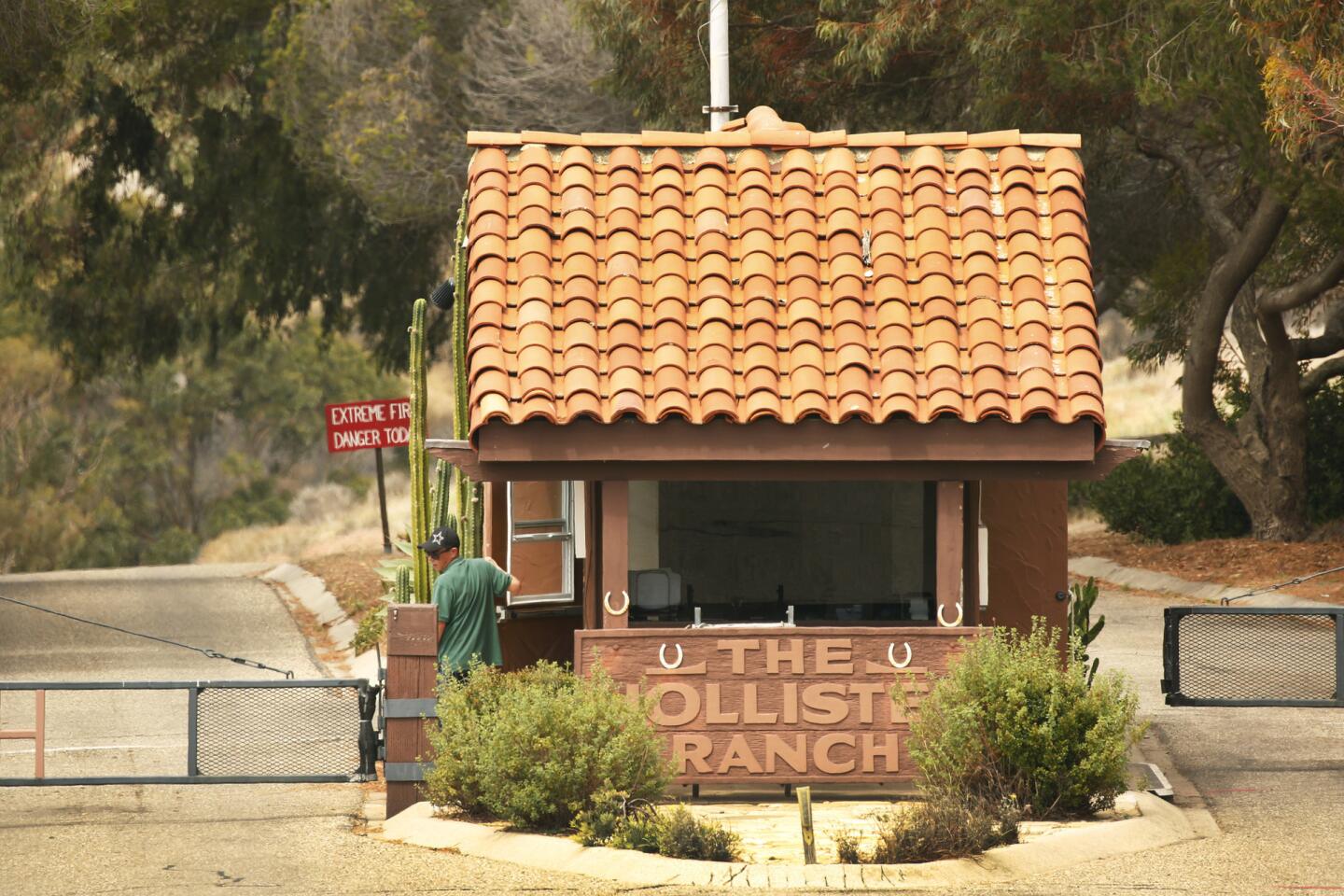

For starters, that stretch of the Gaviota coast — 30 miles from Santa Barbara — is so beautiful, the postcards would look Photoshopped. And residents have eight miles of dreamy beaches and fantastic surf breaks mostly to themselves after years of doing everything in their power — lawyers, lobbyists, gates and guards — to keep the public out.

But there’s another bonus to life on the ranch, and you might not have heard about this one.

The owners — including celebrities and wealthy business moguls — get huge property tax breaks, too, and they’ve been getting them for decades for living on what’s designated as an agricultural preserve.

Collectively, the breaks added up to about $2 million this year, according to a Times analysis.

I teamed with my colleague Ben Welsh, our data editor, to scour Santa Barbara County tax records and find out exactly how much of a savings Hollister residents are enjoying.

On average, property owners get property tax bills that are half of what they’d pay without the special benefits. Nice for them, but the county misses out on revenue that would be available for basic services.

Oscar-winning film director James Cameron enjoyed a $28,000 property tax break last year. CVS heiress Sidne Long got a $22,000 break. Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard saw a $13,000 savings, and singer Jackson Browne got a $3,000 break.

Chouinard, through a spokesman, declined my interview request. Steve Amerikaner, an attorney who represents the Hollister Ranch Owners Assn., said he had passed along my request to the others, but I hadn’t gotten any responses by Friday.

So how did Hollister residents manage to get these tax breaks?

Because of what one state official called “a fairly inventive” but uncommon application of the Williamson Act, which was implemented statewide in 1965 to encourage agricultural preservation. As the California Department of Conservation website explains it, private landowners can enter into contracts with county officials if they agree to land-use restrictions.

“In return,” the website says, “landowners receive property tax assessments which are much lower than normal because they are based upon farming and open space uses as opposed to full market value.”

So far, no problem, right? Preserving open spaces is a good thing. And the tax break does not apply to houses, by the way, only to land.

But at Hollister Ranch, 14,500 acres of rolling seaside hills divided into 136 parcels, there’s one large cattle operation. Thanks to the formation of a cattle cooperative in the 1970s, nearly all of the residents get the tax benefits of being in an agricultural preserve without ever having to saddle up or rope a dogie. They have to agree not to build structures beyond strict limitations, and if a cow comes by, they can’t shoo it away.

“In my humble opinion, it’s probably the greatest abuse of the Williamson Act in the entire state,” said John Gamper, retired director of land use and taxation for the California Farm Bureau Federation.

The residents are homeowners, Gamper said, not ranchers, and for them to get tax breaks violates the intent and spirit of the Williamson Act.

Amerikaner, the Hollister attorney, disputed that, saying landowners around the state lease their property for agricultural purposes and enjoy the tax benefits of Williamson. He referred me to attorney Kim Kimbell, who is part-owner of a 120-acre parcel at Hollister and drafted up the cattle cooperative arrangement more than 40 years ago when he was a young lawyer.

In my humble opinion, it’s probably the greatest abuse of the Williamson Act in the entire state.

— John Gamper, retired director of land use and taxation for the California Farm Bureau Federation

“There isn’t any requirement in the Williamson Act that the landowner be the rancher,” Kimbell said. He added that Hollister landowners “are all actively engaged and at risk over this cattle operation. Now, they’re not shoveling poop and hay, but they are participating in a viable historical cattle operation.”

Gamper said it’s true that the leasing of land for agricultural use is common.

“My issue is subdividing the ranch for residential development under the guise of an agricultural operation,” he said, calling Hollister a maneuver to “reap the property tax benefits of the state’s most important farmland protection program.”

Real estate agents who sell Hollister property extol the virtues of the tax break. “Most underdeveloped, vacant, 100-acre parcels are taxed only a few hundred dollars per year,” says the website of agent Dan Johnson, “the Hollister Ranch Expert.”

If you’d like to live like the king of California, current listings include a five-bed, five-bath Mediterranean-style rancher with dolphin views for $21 million. Or, if your budget is tight, there’s a three-and-two with an infinity pool and ocean and headland views for just $14.75 million.

Not that there aren’t hardships associated with life at the ranch. The Hollister Ranch website says owners “cope with the inconveniences that come with living on a cattle ranch. Cattle and cowboys on horseback are often on the roadways, and vehicular traffic must yield to the four-legged kind. The cattle also leave ‘gifts’ on the roadways that can affect the paint jobs of vehicles.”

Sounds rough, doesn’t it?

But don’t feel too bad for the residents, because “the owners are rewarded for the limitations on use of their property. It is an extraordinary experience to live in the middle of a full-scale, honest-to-goodness working cattle ranch. The cowboys do all of the work, and the owners take pleasure in the ranching ambiance and from the knowledge they are helping to preserve the cattle ranching heritage on this part of the California coast. Furthermore, the cattle function as a free lawnmower service…. And, of course, the owners benefit from reduced taxes for having acquiesced to the restrictions of the Agricultural Preserve program.”

Kimbell, who was gracious with his time and quick to respond to all of the questions Welsh and I threw at him, arranged a conference call so we could hear about life at Hollister from the two residents who run the cattle operation — Kathi Carlson and Sue Benech.

They said they run between a few hundred and a few thousand head of cattle, depending on the season and grazing conditions, and they sell up to half a million pounds of beef a year — much of it to Harris Ranch in the Central Valley.

Benech said they wouldn’t be able to operate “one of the largest working cattle ranches in Santa Barbara County” without parcel owners making their land available.

Do any of those parcel owners ever do any ranching?

Benech said residents sometimes fill water troughs or notify them if a cow is injured.

And that’s worth a 50% tax break?

I sent a few questions about this to Santa Barbara County Supervisor Joan Hartmann, who represents Hollister Ranch. I asked whether she thought her constituents who pay full freight on their property taxes would support $2 million worth of breaks for Hollister residents.

She didn’t answer specifically but said in an email that 70% of the county’s ag lands benefit from Williamson Act tax breaks, and that helps Santa Barbara preserve open space and avoid further sprawl.

Kimbell said land preservation, ecological caretaking and the continuance of a 200-year cattle running history are what Hollister is about. The current cooperative, he said, was conceived as an alternative to plans in the late 1960s for “a massive subdivision.”

I think we can all agree that we didn’t need an asphalted Irvine or a Burbank on the ranch. So sure, it’s nice that the bulldozers never arrived to build the massive subdivision, and it’s great that this part of the coast has been kept as beautiful as it ever was.

But how can any of us know that?

With limited exceptions, we can’t get to Hollister Ranch, even though the beaches are owned by the public. Plans for a pathway to the beach have been stalled for decades by residents, who claim we commoners can’t be trusted not to spoil the environment or interfere with the ranch operation.

So yes, I was irked when a tip checked out and I discovered that on top of all that, residents are getting a tax break.

Kimbell, you’ll remember, owns 120 acres at Hollister, along with partners, in a corporate entity called Rancho Cresta. And the annual property tax bill for those 120 acres of supreme coastal property, along with a small house and guesthouse, is $3,743.

Kimbell agrees it’s a pretty sweet deal, but he argued that the bill has more to do with Proposition 13’s limits on tax increases than with the Williamson Act. The same is true, he said, for the other residents.

What’s true is that Hollister residents are benefiting handsomely from both Proposition 13 and Williamson. In Kimbell’s case, his parcel would be valued at $750,019 under Proposition 13, but Williamson reduces the taxable value to $338,143.

As for the Proposition 13 benefits, that’s worth a moment’s review. Kimbell said corporate ownership entities set up like his can take legal advantage of the famed tax measure. He said he doesn’t necessarily support the loophole, but it exists, and a lot of Hollister residents use it.

How many?

“I would say a significant portion,” Kimbell said. “Maybe not quite a majority, maybe a majority. But there are a significant number of entities that shelter changes in ownership by virtue of Prop. 13 rules.”

Like I said, they’ve got it all at Hollister.

The solitude, the beaches and the tax cuts for living on a “full-scale, honest-to-goodness working cattle ranch.”

My last attempt to enter paradise was by kayak, but that proved to be too dangerous.

Maybe next time by horse.

Twitter @LATstevelopez

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.